Criminal tendencies: the comic genius of Richmal Crompton

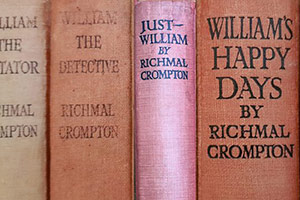

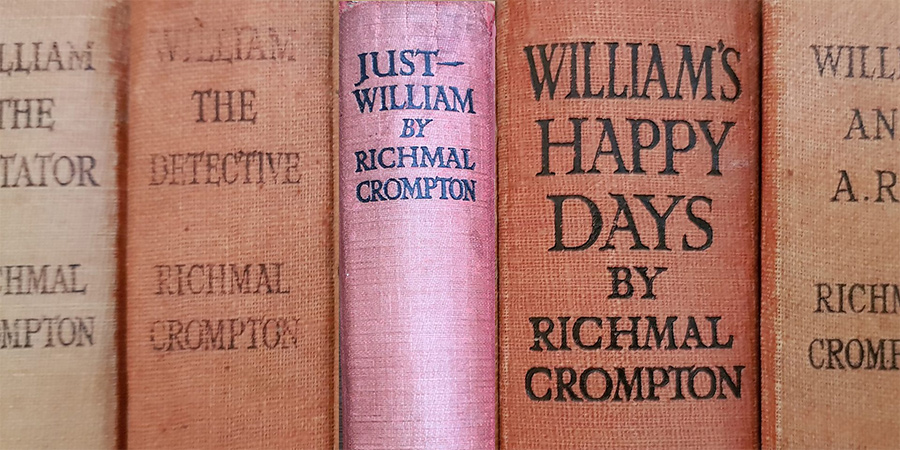

It's 100 years since Richmal Crompton published her first collection of short stories about an unruly, scruffy 11-year-old boy called William Brown. In that time, William has burst the bounds of the stories that gave him life, appearing on radio, television, and film, in the process becoming a cultural institution who overshadows his creator. William is now regarded as an iconic children's character perhaps more than Richmal Crompton as a great comic writer.

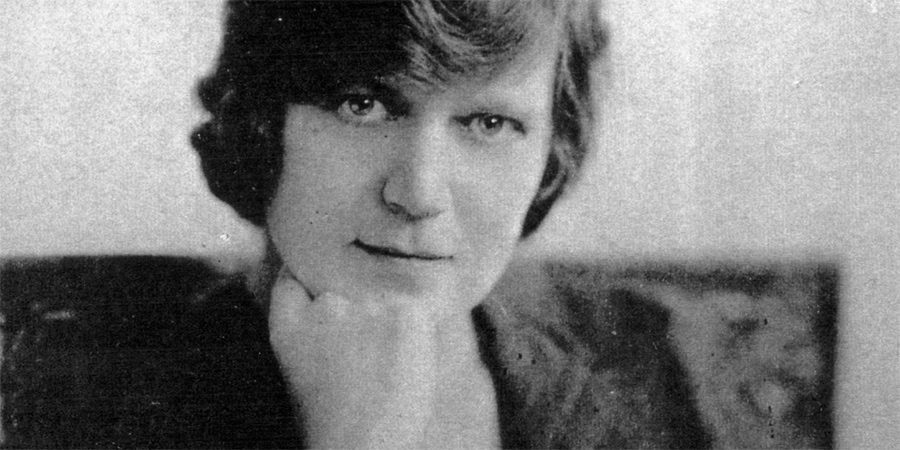

But unquestionably this is what she was. Revisiting the stories while researching the Radio 4 documentary Just William... And Richmal, I've been struck by how laugh-out-loud funny they are, and how sophisticated the comic craft. In discussion of the books, people often comment on how unusually challenging the vocabulary is for children's stories - neglecting to draw the obvious conclusion that they weren't intended for children, but rather as comic stories for adults. Appearing originally in periodicals such as Home Magazine, Crompton was writing exclusively for a grown-up audience, and it shows.

These aren't so much stories about children, as they are about the adult world, as experienced by an 11-year-old boy. Particularly in the early stories it isn't William's voice and world view that stand out, so much as that of the wry, detached narrator. In the first story of the first book, William Goes To The Pictures, while William is sincerely moved by a film he sees, the narrator simultaneously offers her own, more cynical, perspective:

Lastly came the pathetic story of a drunkard's downward path. He began as a wild young man in evening clothes drinking intoxicants and playing cards, he ended as a wild old man in rags still drinking intoxicants and playing cards. He had a small child with a pious and superior expression, who spent her time weeping over him and exhorting him to a better life, till, in a moment of justifiable exasperation, he threw a beer bottle at her head.

One of the overriding features of the stories is this absolute lack of sentimentality; not just about childhood, but about everything. Every character and institution is ripe for mockery.

Richmal Crompton herself was an eminently respectable schoolteacher, a Christian, and a lifelong Conservative - yet school, church, and politics are all viewed with the same bitingly satirical eye. In a story written in 1922, William is described in terms that feel all too prescient 100 years later:

William was frankly bored. School always bored him. He disliked facts, and he disliked being tied down to detail, and he disliked answering questions. As a politician a great future would have lain before him.

Near the end of her life, Crompton would say the William stories had served as "the outlet for all my criminal tendencies". It feels like the only law she obeys in her writing is a comic one; she will go anywhere in pursuit of a laugh.

Perhaps it isn't surprising then, how many British comedy writers remember William as a formative comic influence. Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais shaped the British sitcom with Porridge and The Likely Lads - but it was Crompton that shaped their own writing, and taught them character and plotting. In their book, More Than Likely, they write:

She was great with plots and one of the lessons we learned was that William didn't always have to win; a satisfying ending could go either way. We stole from her shamelessly. An early plot featured a mobile unit checking people for tuberculosis. Terry was trying to pull the radiologist but during a row with his sister Audrey said, 'You won't half be sorry if I've got a spot on the lung!' That was pure Just William.

The further you dig, the more places William's influence turns up. Michael Palin, Terry Pratchett, Caitlin Moran, Neil Gaiman, Simon Nye, Liam Williams, Louise Rennison, Simon Blackwell - some of whom I was fortunate to speak to for the documentary - all cite the William books as an early gateway into comedy.

Throughout the stories you can hear pre-echoes of later sketches and sitcoms. William and Uncle George finds William and his three friends sounding like prototypical Four Yorkshiremen, trying to outdo each other in a series of escalating boasts about injured acquaintances:

"That's nothin'," said William giving rein to his glorious imagination. "I once heard of a man with a false body an' only legs an' arms real." His companions' united yell of derision intimated to him that he had overstepped the bounds of credulity.

Likewise, aspiring politician Mr Morrisse might be an ancestor of Hyacinth Bucket, being "a tall, thin gentleman, for some obscure reason very proud of his name, who went through life saying plaintively, 'double S E, please'." Or there is the perfectly ordered farce of Parrots For Ethel, as elegantly constructed as a Fawlty Towers or Frasier script.

It doesn't feel a stretch to imagine that if Richmal Crompton was alive now, she might be writing sitcoms. Her stories are like Swiss watches, often setting A & B plots in motion within the first couple of pages, before colliding them in gloriously chaotic fashion. The world of her stories is incredibly rich, prefiguring sitcoms like The Simpsons or Parks & Recreation, where the 'sit' extends to an entire community; William's village (never named or precisely located) is as richly drawn and populated as either Springfield or Pawnee. Crompton calls on a cast of recurring and one-off characters, including William's placid mother, irascible father, hysterical brother, and flapper sister, often rotating William into the background and allowing them to take centre stage. Beyond William's immediate friends and family, there are the noveau riche Mr & Mrs Bott and their daughter Violet Elizabeth; the spiritual artist siblings Archie and Auriole Mannister; the militant vegetarians the Pennymans, determined to help the village return to "the morning of the world"; the appalling (and suspiciously Christopher Robin-like) infant, Anthony Martin... It's an endlessly deep bench of comic characters, who drop in out of the stories, variously serving as William's allies, antagonists, and sometimes just his unwitting entertainment.

Richmal Crompton wrote about William for exactly 50 years, always situating him in the present day, and the stories serve as a satirical social history of the middle part of the 20th Century. In the 20s, William is being mistaken for a servant in a manor house, and flirting with Bolshevism; a decade later he is doing his bit collecting scrap metal and disposing of unexploded bombs; while by the end of the saga he is encountering pop stars and being gifted a Beatles' LP.

Over the course of her career, Richmal Crompton gradually acceded to the popular idea that she was writing for children - more likely to be mentioned in the same breath as Enid Blyton than PG Wodehouse. In the last 10 or so books, the comic spark begins to fade. The narrator is heard from less and less, William and his friends' voices becoming increasingly dominant, and their adventures more straightforward.

But the comic genius of those first 30 books remains undimmed, their insight into human nature timeless. Picking them up today is like being reacquainted with a very funny friend - one who invites you to share her good-natured amusement at the gentle absurdities, hypocrisies, and vanities of her fellow creatures. William is inarguably one of the great comedy characters; but so is his creator Richmal Crompton one of the great comic writers. She deserves to be remembered as such.

Just William... And Richmal, presented by Edward Rowett, is available to listen to via BBC Sounds

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more