What is character?

Dave Cohen takes a look at character...

I read a lot of scripts, from writers at all levels of experience, and at some stage I'll notice inconsistencies in how characters are portrayed. I notice it watching comedy on TV, at the movies and in novels. It's quite rare to see brilliant characters and I think it's because writers aren't paying enough attention to who their characters are at the planning stage of their writing.

I looked up "character" in the dictionary, and the main definition, which suits us well, is "the aggregate of features and traits that form the individual nature of some person." Yet we use the word loosely, and with contradictory meanings. Sometimes we say that a person has character, meaning they are good to be around in a crisis. But we also say a person is "a character", meaning they're colourful, or you have to be careful in their presence. The opposite, in fact, of someone you'd want to be around in a crisis. Only Jake Peralta in Brooklyn Nine-Nine manages to be both.

In general, when people are creating a new story, the starting point will be a person, the protagonist. Audiences want stories about people being challenged in their lives, and to see how they overcome those challenges. That's why novelists and screenplay writers put so much research into their creation. Only when those writers know everything about the person are they able to put them into the story to see how they respond. Each creation will be pushed to their personal limits, and must find something from within themselves to overcome their difficulties.

This is where "showing character" applies most specifically in books and movies. In comedy, as with drama, the redemption that arrives around the last third of the story invariably comes from the weakness we have been highlighting in the previous two.

In sitcom nobody ever triumphs. Characters fail without knowing why, the following week they come back and fail again. Which is possibly why we comedy writers are maybe less thorough as we bring to life new creations. After all, isn't it enough to say that Basil Fawlty is a snob? Or that Edina is an overgrown teenager? As long as we can keep coming up with funny stories that expose their comedy flaws in the harshest light possible, do we need anything else?

There are a few issues I keep seeing when I watch comedy on TV. A character has a funny scene but there's another person with them and, although this character should also be funny, or even just interesting in the scene, they're often only there to give the funny person someone to talk to. Or I'll be reading a scene where two or three people are all saying funny stuff, but the jokes are interchangeable, and I forget who the individuals are.

I think we aren't working hard enough to flesh out our comedy characters, and across a series of articles I'll be looking at how best to do this. I'd like to start with a simple counting exercise: One, two. Every sitcom is usually based around one person, a monster, or two people: an odd couple. Some shows have more. Modern Family is an astonishing mix of monsters and odd couples - Jay and Gloria, Phil and Claire, Cameron and Mitchell can be one or the other at any stage in the episode.

The Monster

A monster is a "larger-than-life" protagonist, antagonist, completely lacking in self-awareness, hideous, unlovable yet compelling misanthrope. Somebody who is always fighting battles without realising their biggest enemy is staring back at them in the mirror. Whatever we write, we are nearly always looking for that character.

If you know someone like that, and we all do, you should think about fictionalising them. Performers Steve Coogan, Jennifer Saunders and Ricky Gervais all recognised individuals from their lives with those traits, and possessed exactly the necessary amount of self-awareness to realise that there were large elements of their own personalities in these people. Alan Partridge, Edina Monsoon and David Brent are exaggerated versions of Steve, Jennifer and Ricky, placing their own worst faults under a microscope.

They are all writer-performers who remain at various levels in a position to develop their own projects. We mortals, and those for whom writing is the sole occupation, have to look harder and further, and do more work in the creation of our characters.

In the first episode of One Foot In The Grave, security guard Victor Meldrew is made redundant, and replaced by a machine. Even before we get to know Victor, before Richard Wilson brings the character to life, before we become aware of the writer David Renwick's complete mastery of the farcical plot, we learn what the show is about. A man whose life has been defined by work, and not especially noble work, suddenly finds he's out of it. Too old to retrain, or learn new skills, he is now a man living at home with too much time on his hands.

Recently someone pointed out that on Sitcom Geeks we tend to talk about the same characters over and over - the obvious ones from the hit shows. It's useful for us to do this, as most people will understand these reference points - but it's good to remind us that we have a tendency to fall back on familiar names and faces, so I'd like to talk about two recent shows - one by a writer and one by a writer-performer, and explore the larger-than-life content.

In the exact opposite way that Miranda being literally larger-than-life is an important aspect of her sitcom, Tom Hollander's size is an important feature of Rev, by James Wood (although Hollander is also credited in the early episodes). The Reverend Adam Smallbone is a small, small-town vicar who has moved to a big church in a big city where he is supposed to be the cheerleader for the Biggest Story Ever Told. In Rev, everything else apart from the main character is larger-than-life.

The show deals with big themes like race, poverty and the existence of God: here is a man looked upon by the community to provide all the answers but he's not even sure he's in the right job. All the time he is dwarfed by the huge problems of where he lives, the huge church he works in that echoes to the sound of emptiness and his own huge crisis of faith. Everything about Rev is about the exaggeration of size.

Monster is too harsh a word to describe Tracey Gordon, the creation of writer-performer Michaela Coel from the recent Channel 4 hit Chewing Gum. But the world and people she creates are big and broad. Tracey has one aim in life, to lose her virginity, and create the monster with two backs.

It's a familiar story, but with many twists. It's unusual for the lead in this kind of show to be a woman, and for such a well-drawn, flawed female character. The show has hopefully blown away the kind of fears well-meaning white liberal producers have had in the past about showing women and black people as weak, misanthropic comedy characters.

There are many larger-than-life aspects to this show - at one end of the spectrum Tracey's devoutly religious sister, who is almost as obsessed with sex as she is, and at the other her friends for whom sexual activity is part of their everyday life. In this sitcom the act of sex itself feels like the monster, our most basic human act that we are expected to treat with religious respect and awe, while all around us it's impossible to avoid its ubiquitous commodification, and assume that everyone else apart from us is doing it all the time.

Odd Couples

The odd couple is one of the oldest comedy pairings in literature and theatre. Shakespeare's comedies have them, the 18th century duo of James Boswell and Doctor Johnson is a typical example, while Laurel & Hardy inspired several generations of physical and verbal comedy pairings. Working on Horrible Histories I recently discovered that Gilgamesh, apparently the oldest story ever recorded, from thousands of years ago, has an odd couple at its centre.

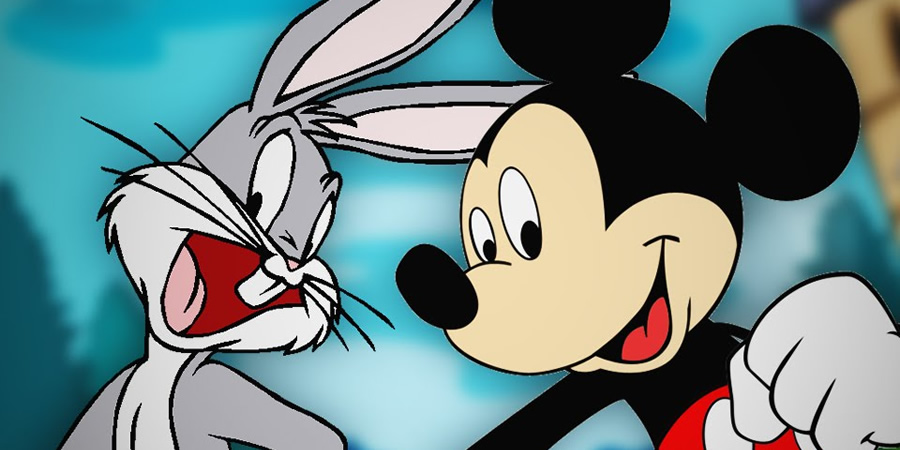

In his entertaining memoir Conversations With My Agent, Cheers writer Rob Long talks about Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse, and how they relate to the world of comedy writing in the US. Every comedy writer, he says, wants to write Bugs Bunny. Nobody wants to write Mickey Mouse.

Mickey is cute (yuk) but Bugs is witty; Mickey is soppy (yuk), Bugs is mean and cruel and cool but don't we all love him?

I'd like to update this idea, and talk about not just comedy writers, but performers, and indeed, the whole spectrum of comedy. I would say, and this is the kind of massive generalisation that could get me a job as a journalist, the entire comedy world divides into two so that you are either John Lennon or Paul McCartney - yes, women and non-Liverpudlians too.

Lennon and McCartney represent a classic comedy set-up, the odd couple. Frankie Boyle and Michael McIntyre if you like. Now there's an odd couple sitcom I'd love to see.

In the comedy writing and stand-up worlds, everyone would like to think of themselves as John. He was by all accounts a funny guy, and could easily have had an alternative career as a stand-up, or even a career as an alternative stand-up. He was a fascinating complexity of contradictions: opinionated and generous, mouthy in public yet lyrically sparse, rude and kind, often downright unpleasant, taken before his time and a Working Class Hero. A British Bugs Bunny.

Paul - that's Sir Paul to you now, Sir Michael Mouse, darling of the establishment - is nice, and sweet, and just keeps making music, which is all he's ever done, and sings about frogs and raccoons and Mickey Mouse silly love songs, and the man's even got the nerve to still be alive.

The British comedy show that best illustrates the Lennon and McCartney love-hate relationship is The Likely Lads, featuring the characters of Bob, played by Rodney Bewes, and Terry (James Bolam). Written by the great writing double act of Clement & La Frenais, each character brilliantly represented an aspect of working class life in the 1960s.

In the 60s there was just enough paid work, social mobility and house building for working class people to believe they could, if they worked hard enough for "the man", become middle class. Squeaky clean Bob wanted nothing more than to settle down in a nice little house with a nice little family, and that's exactly what happened. Terry was angry, he wanted more, he was inquisitive about the world, and for his troubles, ended up joining the army.

In the 70s when they were successfully revisited in Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads?, the differences between Bob and Terry were as heightened as they had become by now between John and Paul. Terry lacked the millions of John, the New York arthouse lifestyle or the exotic conceptual artist wife, but for both of them the 60s dream was over.

The differences were more marked and the comedy harsher, but the odd couple at the heart of that show were totally believable. And as Bob's dream of suburban bliss crumbled before him, the standard message of the British sitcoms of the time remained intact - whatever type of working class person you might be, remember your place and don't try to rise too far above it.

The Gilmore Girls comedy drama is one of the greatest odd couple shows. At different times mother-daughter Lorelei and Rory are Abbott & Costello, Patsy & Edina, Groucho & Chico, Thelma & Louise. Lorelei and her mother also have a great Bette Davis-Joan Crawford thing going, while Rory and her friend Paris are frequently as funny a pairing as Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza.

Occasionally I like to look at some of the relationships I have with comedy partners. I work with other writers, producers, performers and directors. What are the extremes of these couples? That's where you'll find good comedy because it's based on the truth of your own personality, but an exaggerated version of it.

In some cases I feel very much like Lennon, the naughty boy in the class who will say something to get a reaction. In other relationships I find myself reining in the other person, trying to bring our extreme comic ideas back to some kind of centre ground, hearing a little voice sneering "crowd-pleaser" into my ear.

I could squeeze this Lennon-McCartney analogy dry but the point I'm making, hopefully, is that mismatched couples produce great comedy. By the way, Paul never gets any credit for his love of obscure conceptual art (he introduced John to Yoko), his amazingly innovative work as a producer and his continuing ability more than half a century on to stay in tune with the best contemporary music. John's been dead nearly 40 years but Paul still can't quite let go of the fact that he doesn't get as much credit for the old songs as he thinks he deserves. That continuing irritation at this perceived slight means that even Mickey Mouse can have a comedy flaw worthy of exploration.

For more articles on defining characters, see BCG Pro's Inside Track Library

This article is provided for free as part of BCG Pro.

Subscribe now for exclusive features, insight, learning materials, opportunities and other services for comedy creators.