How to pick up radio credits

October 1983 marks the 40th anniversary of the death of Earl Tupper, the Costa Rican designer who was best known, you might not be surprised to discover, for inventing Tupperware.

I mention this because it coincides with the 40th anniversary of my first ever BBC writing credit, which I gained on the topical radio show Week Ending.

And while I can't vouch for this, I can almost guarantee that there will have been a joke at the end of the episode that went out the week that he died commemorating the passing of Mr Tupper. And it will almost certainly have been:

Earl Tupper, the Costa Rican designer who moved to the US and invented Tupperware, died this week. At the funeral Mr Tupper was buried in a see-through plastic box, one end of which snapped after three uses.

40 years on the inventions are different but the jokes are the same. If you want to know what happened at the funeral of the man who invented the USB stick, google it. You can probably hazard a guess.

I can't remember if they used the Tupper joke but have no problem at all remembering what my first Week Ending credit was for. The story was something to do with Britain having to negotiate with China regarding the future handover of Hong Kong, and Margaret Thatcher had put her favourite diplomat Sir Percy Cradock in charge.

The nearness of his surname to that of a then famous TV chef called Fanny Craddock was enough for me to write a sketch in which Sir Percy had his own cookery show and concocted some recipe for improving relations between Britain and China.

It was my first week of writing for the show and I can honestly say it was one of the happiest moments of my life. I'd quit my job as a journalist two months earlier, and here I was in the Big City doing what I'd always dreamed of.

I spent another three years writing for Week Ending and can barely remember more than half a dozen of the hundreds of lines and sketches I went on to write for it.

You always remember your first time.

Over the next couple of months I got more sketches and jokes on the show. Not every week. One of my strongest memories of that period was turning on the radio at 11 o'clock on Friday night, listening intently from start to finish. Half an hour later I was either ecstatically happy or utterly inconsolable.

Getting a credit on the show (and hearing my name read out at the end) set my mood up for the rest of the weekend. Failing to get anything on proved that I was wasting my time and moving to London had been a huge mistake.

So believe me when I tell you that every time I see your name at the end of the credits of Breaking The News (they're sent every Monday by email) I get VERY EXCITED! If we've been in touch before I may send an email congratulating you.

It's 40 years since I went through that experience but I remember the feeling like it was yesterday.

This is one other thing that hasn't changed since I started writing comedy: getting credits on topical radio shows is still the quickest way for any writer to become known to producers. And producers are the people who pay writers for their work.

It was true when Simon Blackwell (The Thick Of It, Breeders, Peep Show) got his, and Georgia Pritchett and Tony Roche picked up theirs in the 1990s (they went on to write for Succession). And it's still true now.

I know many of you reading this have long since decided that you're not interested in the news, and there's no point in even thinking about trying to write topical comedy.

But as my example proves, knowing or caring about politics isn't the most important requirement.

Like many of the Week Ending writers I despised that Government. Secretly I hoped that my hilarious jibes would bring the Thatcher Junta crashing to its knees and usher in a glorious era of kindness and socialism under the steadying hand of, er, Neil Kinnock.

In October 1983 I was happy to settle for a bunch of stupid jokes about Britain's recipe for improving relations.

There was almost nothing in that story about Sino-British relations that found its way into the sketch. The whole, flimsy basis for my 90 seconds of nonsense was that two people had similar names. It wasn't even spelt the same way. And the format was one you will have seen and heard a thousand times on sketch shows - a straightforward parody of a TV show that already exists.

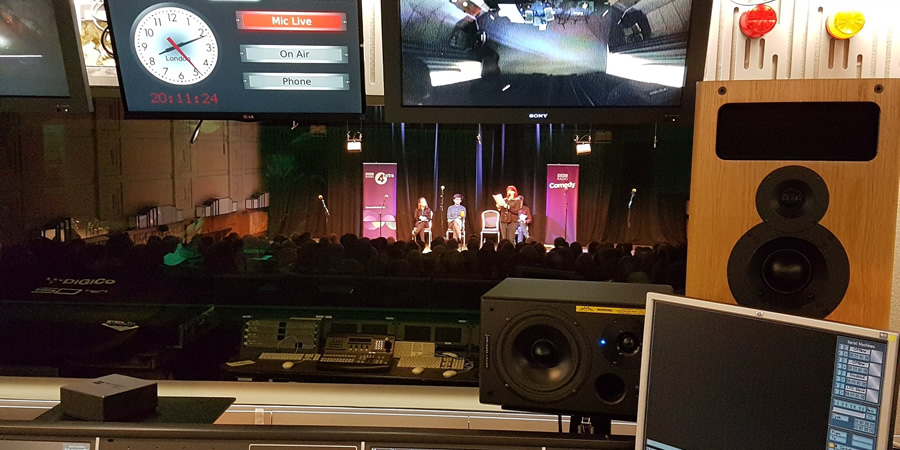

The topical radio season kicks into gear again in the next few weeks. If you've been trying to get on there without success so far, keep at it. I mean eventually you might decide to stop but be sure to have given it a really good go before that.

And if you've never considered the possibility, now is the time to start.

This article is provided for free as part of BCG Pro.

Subscribe now for exclusive features, insight, learning materials, opportunities and other services for comedy creators.