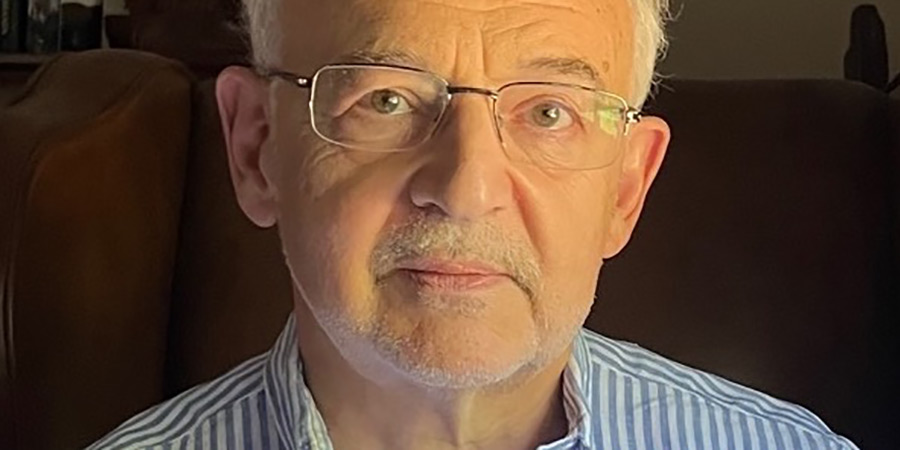

David Renwick looks back on his comedy writing career interview

In this first part of our epic interview with prolific comedy writer David Renwick, we chat about his early days in comedy, writing for The Two Ronnies, being wined and dined by Spike Milligan and coming up with calamitous catastrophes to befall Victor Meldrew in One Foot In The Grave.

At the beginning of your career, you and Andrew Marshall were of a stable of comedy writers working at the time like Peter Spence, Colin Bostock-Smith, Simon Brett and others. Was that a nurturing, supportive environment for you, as writers working your way up?

Yes, I'd originally sent some sketches to David Hatch, the producer of Week Ending and a member of I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again, a show I would always listen to avidly at school, which I suppose is what first got me interested in comedy writing. He wrote back saying he'd like to hang on to them for a bit, to see if he could use them somewhere. And that was the first time my stuff hadn't been sent straight back by return of post. It led to a meeting with him and Peter Spence, who was then, I think, writing all of Week Ending on his own.

One of my sketches gave them an idea for a series about a comedy factory, which was called The Next Programme Follows Almost Immediately. Pete pretty much wrote the whole thing, with Chris Langham coming in on the second series, and I just submitted a few bits and pieces. I was only 19 at the time, but it meant I got a toe in the door at BBC Radio. When Week Ending came back, I was invited to contribute to that, on spec, which I did for the next four years while I was working as a reporter on the local newspaper.

Whenever I got a day off, I'd go in and meet all the people who worked on the show, as you say, Colin and Simon, and Andrew Marshall and Chris Miller. And we'd all break at lunchtime and go off to Yates' Wine Bar, round the corner from Aeolian Hall in New Bond Street ...

Those were the days!

Yes, well that's how Andrew and I first met and began working together. I think the fact that we were both non-public school, which slightly set us apart, meant we felt more comfortable with each other.

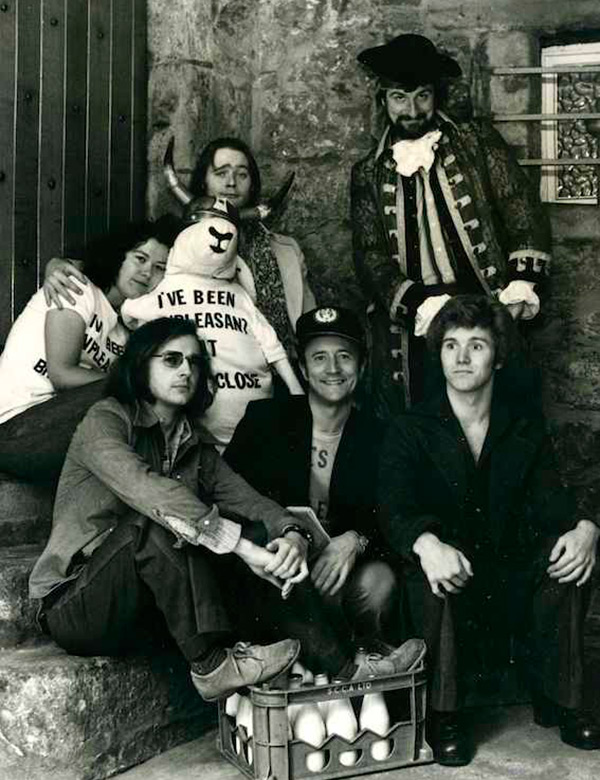

To begin with in those days, I was certainly very insecure, and aware of my working class background. Although by 1976 I must have loosened up a lot more, because that was the year I did a revue in Edinburgh, with John Lloyd and Douglas Adams. It was called The Unpleasantness at Brodie's Close, and we ran it for two weeks, very successfully as I recall, because our credentials as radio comedy writers made us a bit of a novelty.

The whole thing was organised by another writer, John Mason, and Douglas and I shared a bedroom at the house of one of John's friends. I remember him talking in his sleep, but I wasn't astute enough to write any of it down, or I might have had a best seller on my hands. Anyway, later that year Andrew and John Mason and I came up with a new show for Radio 4 called The Burkiss Way, which eventually ran for 47 episodes.

The first full radio series you co-wrote was Harry Worth In Things Could Be Worse, what was the transition like from Week Ending to a show where you had to come up with the bulk of the ideas?

It was hard work! David McKellar came up with the original idea. He was from a writing generation above me, who'd worked on The Frost Report and did a lot of stuff for Frankie Howerd.

Chris Miller had put us together, and we ended up writing a pilot that was meant to star Peter Jones. I suppose there were some early echoes of Victor Meldrew, because it was all deliberately doom and gloom, but very surreal. The BBC liked the script, but didn't want Peter Jones and more or less insisted it should be Harry Worth. And we're really going back into comedy pre-history here, this was someone who'd starred in a string of successful TV series in the 60s and 70s. But it had all gone a bit quiet for him lately, and I think they were looking for a way to relaunch his career.

So we made the pilot and the BBC commissioned another twelve. And that really was hard going, because although Harry was the loveliest, sweetest man, he was infuriatingly picky about the material. Our surreal approach was quickly abandoned, and we ended up restyling it, into something more Hancockian. I'm not sure it was our best work, but it was definitely a learning curve, and I had the experience of working with the wonderful Miriam Margolyes.

As you're known for your complex plotting, was there a freedom in writing in such a wide variety of comic styles, from Roy Hudd to Mike Yarwood and Spike Milligan?

One thing I feel I've always had is a chameleon-like ability to tailor my writing style to fit almost any comedian or genre. Working with Roy on The News Huddlines was another key stepping stone, after Week Ending where there was no audience and you could just write something pithy that made a point, but it didn't necessarily have to be that funny. The News Huddlines was recorded in front of a live audience, so it was all about generating laughs. And with The Two Ronnies, because I'd always adored those Ronnie Corbett chair spots, when Spike Mullins stopped writing them, I found it a relatively easy thing to replicate.

You mentioned Mike Yarwood, who of course was a multitude of styles all in one. So that was the fun of it, finding a way to inhabit all those different personalities. I remember him once saying, after I'd written a routine for him as Bob Hope, "these jokes are good enough to give to Bob himself", which was all very flattering, and liberating.

Of course, when you're writing for a comic fronting their own show you have to defer to their choices and judgment on everything, because they're the ones taking the credit or the flack. And you're just there as a hired hand. Which was exactly the relationship I later drew upon for Jonathan Creek and Adam Klaus - Jonathan is the largely unrecognised figure in the background, who is nevertheless an integral component of the performer's art.

Writing for Spike Milligan, were any ideas ever considered too outlandish, or was it a case of coming up with the craziest things you could?

I don't think you'd say anything was ever too outlandish for Spike, quite the opposite. It turned out he'd been quite a fan of The Burkiss Way and End of Part One, and one day, totally out of the blue, we got a call from our agent saying 'Spike would like to take you to dinner tonight'. So we ended up meeting him at the Tratoo in Kensington, where we talked about everything except the TV show.

Afterwards, Andrew came out saying it was like he'd just been on some strange acid trip. Spike would just sit there firing off in all directions, one minute hysterically funny, the next just completely incomprehensible. Such a mixture, but you couldn't help loving him. At our second meeting I remember he said to us: "Go away and write whatever you want to write. Whatever makes you laugh, be as way out as you want. Fuck the audience, they didn't understand Van Gogh in his lifetime, so I think I'm in good company."

And so Andrew and I would always try to write something with some kind of central comic concept to it, however wacky or bizarre. But he would then take that away and start adding in all kinds of extraneous, destructive elements. And you'd just think 'No, please leave it as it is, you don't need to bring in George Formby as a Black and White Minstrel getting a custard pie in his face, you're losing the whole idea.' And yet alongside all the rubbish, he would come up with stuff that just blew you away. He had the most amazing imagination and facility for comic genius. In every show there was usually at least ten minutes, I would say, where you'd be on the floor laughing.

That final series, which should originally have been called Q10 he decided to re-title There's A Lot Of It About. For reasons known only to himself. When he signed my copy of the published scripts he wrote "There wasn't as much of it about as we thought".

There were various attempts after that to float some other Milligan projects for the BBC and Channel 4, in which Andrew and I would have been involved, but none of them came to anything.

It is fair to say that The Two Ronnies' Mastermind sketch is one of the most fondly remembered sketches of all time. You adapted it from one you'd written for The Burkiss Way. Was it as difficult to write as it looks?

Well, like so many supposed classic moments in comedy, I can never quite understand why they become so memorable, at the expense of everything else that was in a series. The dead parrot sketch, for example, of all the wonderful sketches in Monty Python. Or 'Don't tell him, Pike!', out of all the brilliant moments in Dad's Army.

As you say, it began as a much shorter sketch on The Burkiss Way, with different lines but the same premise. In 1980 when I was scrubbing around for new ideas for The Two Ronnies I just decided to dust that sketch off, with a new set of jokes, and see if it worked. As I've said many times, I then completely lost faith in it. It had gone down well enough on radio, but I just worried that The Two Ronnies was a more conventional show, and they'd think it was too contrived. In the event, the producer Paul Jackson, rang me up to say it was going straight into the first episode. Ronnie Barker was planning to record it twice so the audience would get all the connections the second time round, but it played so well the first time, it wasn't necessary.

I think that was largely because you get all the laughs mostly through rhythm. And you don't have the time in that split-second to see how Corbett's answer relates to a question three speeches ago. In point of fact a few of the answers don't entirely make sense, like "What sort of person lived in Bedlam?" - "A parachute", but the audience still laughed.

When they did The Two Ronnies Sketchbook many years later, and Ronnie Barker was sadly quite frail, they did a line on the news desk about the death of this very disheveled person, whose body "is now lying in a state." And dear old Ron, when he did it the first time, misread it as 'His body is now lying in state.' Of course it got a big laugh, but he knew he'd got it wrong and immediately asked to go again. But the audience, as always, were so geared up to laugh -

And because he's Ronnie Barker.

He was Ronnie Barker, and the two of them had that twinkle and indefinable quality that just made people want to laugh at them. There was a joke Mike Yarwood did once as Frankie Howerd, not one of mine, that went "A lot of people don't realise I've got royal blood in me - I was bitten by one of the Queen's corgis". Big laugh. And I was up on the studio gantry watching with Barry Cryer, saying 'But that doesn't work! If you were bitten by one of the Queen's corgis, they'd have your blood in them!" It doesn't make sense, but the audience still laugh at the delivery.

But back with Mastermind ... when they later did their stage show at the Palladium I actually extended the sketch, with extra lines, so that every single question and answer properly tied up. So I think that bit I mentioned, for example, became "What did Marilyn Monroe claim to wear in bed?" "A parachute". And then there was some wordplay with Channel 4 and Chanel Number Five, and so on and so on. But ultimately it just became too clever, and especially on a big exposed stage, never ever got the laughs that it did in the intimacy of the TV studio. So we took all the new lines out and just reverted to the original. You must never forget that there's such a frailty to comedy -

Brevity is the soul of wit, as they say.

And you have to be on top of that all the time. There was once a suggestion to include Victor and Margaret in some kind of scene for the Royal Variety Performance, and I said no because it could well have died on its arse in that context. Generally, you have to be a lot broader onstage. That's why I think One Foot would have only worked in a much smaller theatrical space if we had ever done a play.

Ronnie Barker was fastidious when it came to the scripts, would he ever rewrite your sketches?

Well, I remember the first time I went into TV Centre, to meet Peter Vincent, the script editor, and the producer Terry Hughes, there was talk of them doing one of my very early sketches, "The Yes Man interview", which Terry said Ronnie B would probably "tickle a bit". Though when they did finally use it, I don't think it had been changed very much.

My experience generally, writing for The Two Ronnies, was that if they liked the material, they'd go ahead and do it, with maybe some trims, or a new tag, which Ronnie Barker was always much better at than me, but otherwise they would just respect the original text and make it work. It was usually all or nothing in that sense.

Ronnie B of course was always addicted to clever wordplay. There was a Poirot film that Andrew and I wrote, called Murder is Served, with a character called Mrs Bultitude, played by Patricia Routledge. And Ron put in the line "It is your pulchritude that sets you apart from the multitude, Madame Bultitude". That was a classic bit of Ronnie Barker fiddling, that I'd have no objection to. As you probably know, he used to write a lot of the shows under the pseudonym Gerald Wiley, although in later years he said he was finding it harder and harder to come up with new material. That's why those serials in the middle of the show were eventually dropped, in favour of a ten-minute stand-alone film at the end, like the Poirot I just mentioned. And I did about nine or ten of those. Quite a few parodies, like Quatermass, and Raiders of the Last Auk, and Sunset Boulevard, Tinker Tailor, and several others.

It can be difficult to trace who wrote particular sketches. Which other Two Ronnies sketches that you wrote are you proudest of?

Well there are some that tend to get repeated more than others in those compilations. "Crossed Lines", where they're both making separate phone calls, as if talking to each other.

And I always quite liked the one where they're doing crosswords on the train. Corbett struggling with the Sun's Junior Coffee Time while Barker's doing Mephistopheles or something in the Financial Times.

Another one that often gets re-shown, but I wasn't so happy with, is the courtroom where it's all played out like different game shows. I always felt it should have been performed with more gravity, like a very serious murder trial, and not in a spirit of fun, which seemed to undermine the incongruity of it all.

In the very last episode there was a film about a demonic Pinocchio, which Ronnie Barker conceived and then asked me to write up. As an idea it wasn't something I really took to, but they seemed to be happy enough with the result. I didn't think it was the strongest item for them to go out on though.

As well as the fifty chair spots I also wrote some monologues for Ronnie B, and would love to have done more if I'd had the time. The Police Recruitment single I think would be my favourite, which I remember immediately followed the Mastermind sketch. Barker comes on in full uniform with that famous glare into camera: "Good evening, I'm the fuzz. I'm actually a plainclothes officer, but today is my day off ..."

You worked on the American series Assaulted Nuts. Was it a lot different to working on a British comedy, more of a writers' room?

That series was all shot over here. It was the brainchild of Ray Cameron - Michael McIntyre's father - who used to write the Kenny Everett shows with Barry Cryer. Ray was such a great entrepreneur and producer, and somehow managed to set up this transatlantic project, which I think was all filmed inside a big country house, using the different rooms as sets and studios. Andrew and I contributed a bunch of sketches, but I think they had several writers, besides Ray and Barry, working on the show. And the cast was a mixture of British and American actors. Tim Brooke-Taylor, Danny Peacock, Cleo Rocos, and I think Emma Thompson was in the second series. And from the States he'd drafted in the then unknown actors William Sadler and Wayne Knight, who went on to play Newman in Seinfeld. Both of them clearly very strong comic performers, who were destined for bigger things.

Whoops Apocalypse was about a world in crisis with an insane Conservative leader - do you think it's dated at all?

Well I don't think these things ever date do they?

Certainly not these days.

That series was still a very formative part of our careers, our first grown-up series on television. End of Part One, the sketch show we'd just finished, had been relegated to Sunday afternoons, and we were anxious to come up with something that would guarantee us a much later slot. The Soviets had just moved into Afghanistan, and there were serious nuclear jitters as we waited to see how it would all unfold. So that backdrop, as now, was very nerve-wracking, and we decided to use it as a starting point for what we conceived as a kind of geopolitical soap. The show went out at ten o'clock on Sunday nights, and it was our first experience of working with real A-list actors, like John Cleese, Richard Griffiths, Geoffrey Palmer, and even Barry Morse, who'd played Inspector Gerard in The Fugitive.

The film version, which we made a few years later, was obviously inspired by The Falklands War. I don't think either of us could understand how practically the entire population descended into this belligerent, blood-thirsty nationalism, and the way Thatcher managed to use it to hoodwink the country. So once again we devised a prime minister who was essentially mad, but universally adored. We wanted Cleese to play that part, but although he liked the script, and indeed his company Video Arts were lined up to fund the production at one point, he declined, and we got Peter Cook instead. Still one of the best things, I would maintain, that he ever did on film.

One of the most heinous aspects of that whole Falklands period of course was all the gung-ho media coverage, which we were desperate to satirise. In the earlier drafts there was a lot more stuff about the hacks who were accompanying the task force, but we ended up trimming all that back.

Was that why you went on to write Hot Metal, to focus in on parodying the press?

Yes, I mean you almost didn't have to think very hard to come up with ideas. We'd just go out and buy a copy of The Sun, and then maybe add a slight twist to whatever they were printing that day. It was a kind of therapy in a way, that we were able to vent our spleen like that on air. But ultimately I think we failed because most of the press loved it, and the public couldn't have cared less. And sadly, even post-Leveson, nothing has really changed or improved since the days of Kelvin Mackenzie.

You first worked with Richard Wilson in the Whoops Apocalypse film, where he ends up on a cross -

That was the first day of filming I think.

Lucky him!

Yes, he wasn't very happy about it, I think he had to go up half a dozen times before the director was happy with the shot. Later in the shoot he came out to Miami to do a few scenes. That's when I famously re-wrote the graffiti on his bare bottom because I felt the make-up department had been a bit too delicate.

You could say our relationship took off from that point. When Geoffrey Palmer decided to drop out after the first series of Hot Metal, we cast Richard as a very similar fall guy figure. One of the greatest joys was hearing him read out all those screeds of tabloid crap with such undisguised venom. You could tell it came from the heart. And that biting delivery was one of the huge strengths that led me to think of him for Victor.

Victor Meldrew became a lazy descriptor for misanthropy or grumpiness, which is to completely miss the point of his character. So many episodes have him fighting for what is right and fair, most notably Hearts Of Darkness, which to this day remains a shocking episode of sitcom. Did you get a lot of pushback from the BBC when you submitted that script?

Not when we made it. I remember Susie [producer/director Susie Belbin] saying 'this is really strong stuff, can we do this?'. That was as far as the vetting process went in those days. I'd send her the scripts and get her reaction, and sometimes we'd discuss what worked and what didn't, and if there were any issues we'd address them. But there was never a time when it had to go upstairs to be approved, as it certainly would do today, when you'd get half a dozen different executives giving half a dozen different opinions.

The fallout only occurred after it was broadcast with viewers complaining that this sort of thing had no place in a comedy programme. Which was not unexpected. Subsequently we were asked to reduce the number of times Arabella Weir's nurse kicked the old man.

But I had no regrets about that episode. By this point in the fourth series, you're still looking for new ways to keep up the creative momentum. And anything that's going to push the boundaries, and make people sit up, I thought was a good thing. Not because you wanted to upset them, or offend, but more to maintain that essence of real life, rather than just the cosy world of sitcom.

There were certainly some shocking moments - the cat in the freezer, Mildred's suicide.

Well, by contrast, the cat in the freezer is something I would never do now, as a devoted cat and animal lover. This was very early days and I was going for cheap laughs, we were still trying to find our feet. I feel the same way about the tortoise if I'm honest.

Mildred's suicide in the final series also drew a bit of a reaction, and that was a tricky one. Dramatically I felt it was absolutely right, to suddenly overturn the viewer's image of this jolly, slightly silly, figure of fun, to show that she had depression issues. Because that's how life is. But I suppose there's no way a pair of legs swinging outside the window isn't going to look a bit comic, even though it was obviously not played for laughs.

There was a moment in our first Christmas special, Who's Listening, which I only ever saw as rather tragic, where they've agreed not to buy each other presents, but at the end she hands him this new watch, and he gives her a sheepish look and says "Well, I may as well admit that I've done the same thing ... I've bought myself a new watch as well". Huge laugh.

On the page that was meant to be a very sad moment. But it goes back to what I was saying about the rhythm. The whole structure, and timing in that exchange, appears to be setting you up for a funny pay-off. And almost anything that Victor says, like Ronnie Barker, you're conditioned to the idea of it being funny. In the end, the difference between comedy and tragedy, I don't think you can ever say it's purely objective.

That leads rather nicely into my next question, which is about a moment from the episode Timeless Time, when Margaret remembers the son that they lost. That switch from comedy to pathos is a frequent feature of your work, did you plan those moments when you conceived the characters, or did they evolve naturally as the show progressed?

No, I'd given no thought to that at the outset, whether they had a family. It just emerged, completely organically, in the moment. Intuitively you sense that at this point in the action, after a string of often very mad jokes and moments, it was nice to suddenly anchor the whole scene with something serious.

Like the other examples, to lend a sense of reality, which in a way enables you to get away with all the comic contrivances. And it's the absolute searing honesty of that moment, especially in Annette Crosbie's performance, that just takes it to another level for me. Of course, having introduced this fact, about their lost child, I never saw any value in revisiting it. It was perfect in that particular moment. Which is how I've always approached the material, trying never to labour or over-exploit. Too often it can just lead to diminishing returns.

Many of the best episodes of One Foot In The Grave are the bottle episodes. You wrote one in every series from Series 2, perhaps most notably The Trial, which featured Richard Wilson completely alone onscreen for thirty minutes. Did you write them as a challenge to yourself?

From my point of view, it was more about ticking an episode off without having to work out too much of a plot. Each year I'd have to come up with six scripts, and if one of them was all set in some claustrophobic location, like the traffic jam or in the power cut, I could mentally set that to one side and it would very slightly ease the pressure. When you consider the challenge of dovetailing a whole set of routines and ideas into some kind of narrative for all the other five shows, these episodes became relatively easy. But I do stress relatively, because the writing was never anything but hard.

I think it was Susie who persuaded me that Richard could carry an entire half hour on his own. So that became The Trial. The obvious precedent of course was Hancock's Bedsit episode, which was a kind of landmark in situation comedy. That gave me the legitimacy to go ahead with it, to have the character just talking to himself for thirty minutes. You could argue that it's too contrived, like the Mastermind sketch, but sometimes it turns out you can just transcend the contrivance, because you're enjoying it so much. You make the allowances.

One Foot In The Algarve was the feature length episode which featured Peter Cook. Was it a challenge to expand the show to 90 minutes?

I sold it purely on the title. I think it was the week after we'd won a Bafta, so the BBC were quite high on us at the time.

Yes, it took an age to assemble all the various storylines, trying to get a balance between all the comic stuff and the drama. As usual I ended up packing in too much and it required a lot of filleting out in the edit. There was a lot more to the undercurrent of Margaret feeling her age, and that whole strand of Isabella in the shoe shop. She's convinced Victor's having an affair, but he's actually been seeing her to organise a present of some shoes for her birthday. And it all got a bit top heavy.

When we viewed back the first cut it was forty minutes too long, so we had to do a lot of streamlining. I thought in the end there was a lot of nice texture, with the photography and the music, and there was even a kind of imagined murder mystery, which foreshadowed Creek in a way.

Did you always intend to kill Victor off in a hit and run accident, or were there more elaborate plans?

One of my early thoughts was him walking along the street, having just bought a book on positive thinking or something, and a piano falls on him. I'd also once had some fanciful idea of the very last scene ending with Margaret leaving the house and walking out into the empty television studio, around the set, as a kind of meta-statement about everything we'd been watching for the last ten years. But that would have run counter to my whole argument about preserving a sense of reality. And today of course would have been a bit Mrs Brown's Boys.

What I knew was that Victor couldn't die from some hideous wasting disease or something that would be too upsetting to watch. It had to be something, not comic, but certainly less harrowing. I think I came up with the hit-and-run initially to make a point about reckless drivers. But then as I got deeper into the plotting, I realised it would be a much nicer twist to make it Hannah Gordon's character, who Margaret befriends, who's so worried about her own husband she just loses her concentration. Which would make it more interesting and layered.

But I always knew Victor should die in that final episode. I wanted to just draw that line under the series and make it unequivocal. And we made a point of announcing his death in advance, not for the cheap publicity, but because you knew it would only leak out anyway, and we could avoid all that tabloid sensationalism.

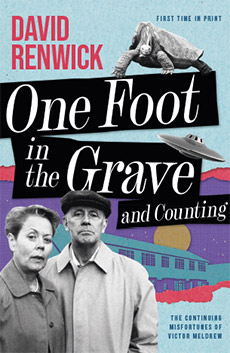

You've been very emphatic in the past about the fact that you killed Victor off to avoid being persuaded to bring him back for specials. What made you want to resurrect Victor for the recent novel, One Foot In The Grave and Counting?

There was no great game plan. I'd finished writing for the screen, and this was just something I thought I'd try, on a whim. I wrote the first One Foot In The Grave novel back in 1992.

There were various ideas I still had, and bits of material from other sources that I thought I could weave in, and it was something to while away the hours really, it wasn't a calculated decision. As with nearly everything in my career it was written completely on spec, because I might have given up after the first chapter.

Once I'd completed it, I then had to hawk it round everywhere and try to sell it, which was not an easy task. There were several rejections and passes, sight unseen, and people who just didn't bother to respond at all. Eventually I was directed to Fantom Publishing, by Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran. And I did at least achieve my goal of seeing it in print. I feel it's a much stronger piece of work than the first book, but I suppose you'd hope that would be the case after thirty years!

What did you think of the Father Ted episode is which Richard appears as himself, plagued by the catchphrase?

Of course it was very funny. I'm a big fan of Father Ted. Richard had come in one day to rehearsals saying he'd been approached to do it, and what did I think? There was no way I was going to refuse, though at that point I don't think I knew exactly what it was about.

Quite cathartic for Richard I imagine.

Yes of course, it certainly played into Richard's hands, he gets besieged with that all the time. I think the idea arose when Graham and Arthur found they were sitting behind Richard watching Cirque Du Solei, and amused themselves by imagining his reaction to all the acts was to shout 'I don't believe it!'. And it developed from there. It seems to get repeated as often as the clips from One Foot In The Grave, and I can imagine some people are more familiar with that than the show it's referring to.

Our interview continues on the next page. He talks about the puzzling plots of Jonathan Creek, working with Rik Mayall and his lifelong friendship with David Jason.

Read Part 2 of the David Renwick interview

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more