Consolevania turns 20: Robert Florence and Ryan Macleod on making comedy out of video games

When Tom Crowley was a teenager, a scrappy homemade web series about video games, Glasgow, friendship and Fray Bentos pies showed him that he didn't need to wait for permission to make his masterpiece. Now, as that series turns 20 years old, Tom takes time out from his own self-published efforts to speak to its creators, Robert Florence and Ryan Macleod, about where Consolevania came from and what made it special.

A dirty-faced, cherubic Glaswegian boy squints into the camera and begs for answers from a GamesMaster-style oracle, a long-haired young man named Kenny. "Kenny, I'm playing Oblivion. Is there any secrets?" he pleads. "Here's a secret," Kenny roars back, "Your maw's shaggin' your uncle."

Consolevania is a video game review show. It's also a sketch comedy series, an experimental video art installation, the world's longest mix tape and a chronicle of the lives of its creators, Robert 'Rab' Florence and Ryan Macleod, from the show's debut in March 2004 up to the present day. Way back when I first discovered it, around the start of its second series, my 17-year-old mind was warped forever, and not just by the frequent images of the hosts' nude inner thighs. As a ginger-wigged Ryan attacked a flailing Rab wearing a cardboard box on his head, ostensibly to promote a nonexistent video game called Manpuncher Versus Boxhead, my world was expanding.

This wasn't a television format that had been developed, focus grouped and slickly polished for the attention of a mainstream audience, concocted in the cloistered editing suite of a production company's cocaine-dusted Soho offices. This was just made by people. These people thought this would be funny, so they worked out what to say, filmed it themselves on a camcorder and edited it together on their home computer. Moreover, this wasn't a taster tape for some hypothetical programme, this was the final product. It was singular, strange, candid, innovative, unashamedly niche and gleefully silly. They wanted to make it, so they did, and here it was.

"I think we just had a lot of creative energy we wanted to let out. It was genuinely a case of making the show we wanted to watch," remembers Rab, "Consolevania was really just an extension of what we were into, as pals."

Ryan agrees that there was no particular plan at the outset, "At the start of 2004, I was 25, about to turn 26, still living with my mum. I got thrown out of college about 6 or 7 years earlier and I still had no clue where I was going in life." This scattergun energy produced several hour-long episodes packed with reviews, erratically-shot original material, game footage re-edited into surreal sketches and vox pops captured on the lairy Friday night streets of Glasgow. Ryan remembers their guiding aims, "It had to avoid being like anything else that was out at the time, it had to avoid appealing to everyone and it had to not be shite."

When the first few episodes were finished, they were handed around physically, on discs. "I can mind taking in some data discs of Consolevania episodes to pass around the office when I worked in insurance," says Ryan, "I honestly cannae remember us thinking Consolevania would do anything for us, I just knew that making stuff for a laugh was much, much better than going into an insurance office every day." Rab shares this sentiment, "We were mailing out discs and just enjoying ourselves. A really innocent time. A great time, really."

Hold on. Why did they bother burning and handing out the episodes on physical media, rather than just uploading them to YouTube and becoming game-streaming millionaires? Because it was 2004 and YouTube wouldn't even exist for another year. Wait, that can't be right. This cannily-observed spoof of the ludicrous characters and laughable pomposity of video games predates the platform that consolidated that culture? Admittedly the comic extremes of that world had been around for decades before, documented in magazines and online forums, but it still feels a little bit prophetic.

Looking back at Rab's early character Legend, a swaggering, self-aggrandising esports champion, he seems like a pitch-perfect pastiche of most gaming personalities we know today: a brash American man-child concealing a deeply fragile masculinity. The perfect parody of a video game YouTuber, before such a thing ever existed.

These days, we're spoilt. If you've got a pastime or an interest, whether it's video games, yo-yo collecting or the work of the British television star Leonard Rossiter, you can find subreddits, social media feeds and Discord servers filled with like-minded folks sharing opinions, memes, podcasts and videos all dedicated to your specific interest. You can cherry-pick the creators whose perspectives on the Rossiter community you like best and watch their whole lifetime's output on your phone while you're going to the toilet. So, if you're too young to remember, imagine what it was like in those early days of online video publishing, when you had to trawl news websites and message boards to find interesting new creators who shared your interests. Then, if you did, your only option for watching them was on your computer, at your desk. These esoteric joys were hard to find, and were all the more precious for it. Rab says, "We just liked talking about games and making obscure references, and we knew that any audience we did manage to pull in would be our kind of people, as Barrymore might say."

I've spent a lot of my career making my own work. From my earliest days in comedy, sellotaping props together for a month at the Edinburgh Fringe with the group Four Sad Faces, through very quickly working out how to make a radio sitcom with the rest of the Wooden Overcoats team, right up to the present day, when my passion, my pet project, my primary comedy outlet is my one-man sketch comedy podcast Crowley Time with me, Tom Crowley. In these projects I've always felt like I'm chasing a particular creative satisfaction, the sense that what you're making is exactly what it needs to be, that it's entirely the product of the personality and the sweat of the people behind it, and that more effort went into it than was strictly necessary because it was loved. I've also learned to sniff out that sensibility in other people's work, whether it's in comic books, indie games or YouTube channels, and to crave it. In recent months, with the 20th anniversary of Consolevania approaching, I've begun to realise that it might be where I first caught that particular whiff. "I think we just wanted it to be honest," says Rab. 'Honest' sums it up quite nicely.

These types of passion projects have a habit of absorbing every part of their creators' lives, and those of the people around them. "I think the reason why Consolevania means so much to myself and Ryan is that it is so personal," says Rab. "It exists as a bit of a journal of our lives. I can watch it and see my adult nieces when they were kids. I can watch it and see my ma and da, both of whom are gone now."

The soundtrack has always been a key factor, as well, with the 'featured music' section of the end credits being one of very few elements that has persisted throughout the show's life. "I think music was the biggest inspiration," Rab even says, "I would say that Series 2 of the show, which is where I really felt it found itself, is really influenced by a kind of 60s/70s psychedelic thing. Music led a lot of it."

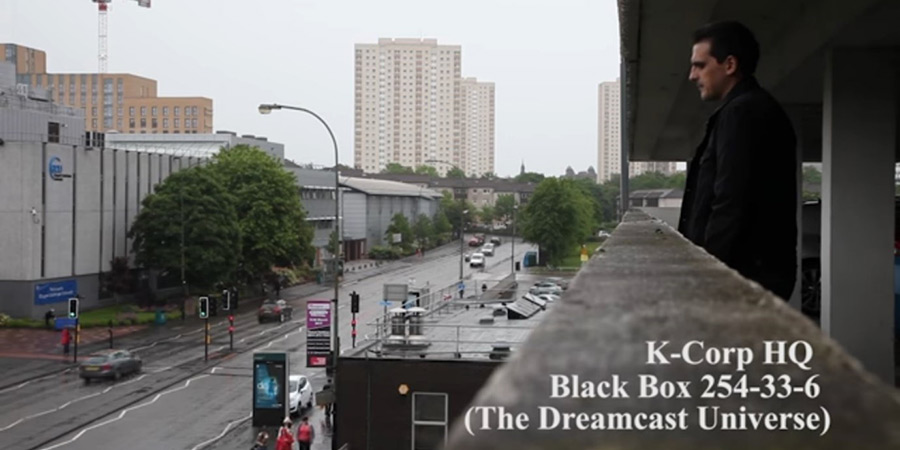

Certainly, as a child of the early 21st Century, bombarded with Coldplay and Razorlight through the radio and telly, I was first exposed to musicians I'd now count as favourites like Elvis Costello, Kate Bush and Aimee Mann in Consolevania. Plus the Doobie Brothers, of course. Here's a typical sequence: near the end of Series 2, Rab and Ryan have tracked down the bent red coathanger that served as the production's first piece of audio kit. When they both put their hands on it, there's a flash of light and the boys disappear, transported to an alternate universe. A universe where the Sega Dreamcast is the most successful home console of all time. All to the strains of The Monkees' ethereal Porpoise Song. Now, that's a funny, surprising and slightly haunting combination of sounds and images that will stay with me until the day I die, especially at times when I'm questioning whether the sketch I just came up with is too weird to bother making.

Of course, this unabashed specificity can, by its very nature, limit a project's reach. "I don't think a show like Consolevania could ever achieve a big audience. It was too personal, too odd, too Scottish. To be frank, a lot of people just couldn't understand what we were saying," remembers Rab. That said, I was part of a not-so-tiny wave of people across the world who did connect with it, as Ryan confirms, "Towards the end of the first series, start of the second, we were using [online file system] BitTorrent to share the episodes and I saw that, by that time, it wasn't hundreds but tens of thousands that were being downloaded, and we'd start to get contact from folk in Australia, America, other European countries." He is keen to keep this in perspective, though, "But it's not like we were packing people into arenas, we were still both living with our parents in North Glasgow doing the usual, eating curries and playin' vidya games!"

Rab adds, "Even when YouTube started kicking off, and you could see that turn everyone was taking into a more consistent, professional online presence - we weren't really interested in generating any kind of growth."

Ryan makes no apologies for the show's peculiar palette of ideas, either, "My dream is that hundreds of years after our deaths, an alien is going to find all the old Consolevania content and get into it, and get all the unbelievably obscure Christopher Walken references I've been dropping into things for years. All aliens are aware of and love Christopher Walken, by the way."

I'm not proud to admit it, but I've been similarly indulgent in my time, and my worst excess was Consolevania-inspired. Four Sad Faces used to have a sketch called Tiny Michael Caine about, you guessed it, an alternate version of the famed actor if he were the size of an Action Man. At one point, distraught, he shrieks, "I'm still trying to get my tiny emails!", a reference for nobody but me. But I'll tell you what, it made it onto Radio 4 Extra.

Whether we got Ryan's Walken nods or not, those of us who made up those tens of thousands of BitTorrent hits were overjoyed to find a games-related show that took its cues from Reeves & Mortimer, Adam & Joe and Frank Sidebottom rather than American gaming media's cringe-inducing punts at MTV-style yoof cool or the eye-rolling pseudo-intellectual smugness of so many self-appointed online mavens.

The video game industry was then, and still is, one of vast contradictions. It's a nerdy, arcane hobby that also makes more money than any other entertainment medium worldwide. It's comparatively accessible to independent creators and can directly transform a complete unknown into a wealthy superstar, but some of its biggest-budget, highest-profile products are developed under truly atrocious working conditions. It's a flashy, shadowy, sad, joyous, empowering, embarrassing, brand new, very old mess of circuit boards and escapism. Is it any wonder that this is the ideal lens through which to view it? An earnest Glaswegian irreverence that seeks to mercilessly mock its subject as much as venerate it? What better response to this huge, confused, pompous landscape than Ken Loach's Halo 3?

What's more, if one side of the 'niche' coin is potential alienation, the opposite side is the heightened enthusiasm of the un-alienated. As episodes continued, Consolevania only became more singular, expanding into a homemade cinematic universe all its own. Recurring characters, segments, motifs and obsessions naturally began to emerge with each new episode, all forming an internal continuity that we loyal viewers loved to see developing.

It became woven into our lives, too. Still today, whenever I address a group of people as 'team', I think of Consolevania's TEAM publicly challenging development company Codemasters to a street fight. I still think of analysing the deeper meaning of a piece of media as 'putting on my wank hat'. I can't see or hear the word 'vaporise' without my brain saying, "They're going to be vaporised. They're going to be vaporised."

At the beginning, the show was rarely consistent. "We had no grand vision for the show. We were winging it episode by episode," Rab recalls. Despite being a review show at its core, no rating system survived longer than a single episode. In one, games were awarded a gold, blue or brown ribbon depending on their respective merits, and in the next, scores were communicated by Rab in the guise of psychedelic games design genius Jeff Minter sitting in a cupboard and flashing a torch at the camera. Nevertheless, further episodes led to more complex continuity and world-building and what began as throwaway gags evolved into expansive plot arcs and multiple dimensions. Eventually, Consolevania could pull these strands together to conjure triumphant moments like the long-awaited return of the oracle Kenny in Series 4, a punch-the-air reveal to rival any long-running HBO drama, don't @ me.

It takes time to cultivate such an elaborate network of characters and callbacks, and time is a luxury rarely afforded to British broadcast shows these days, to comedies least of all.

So yes, Consolevania is esoteric and niche and, in real terms, was only ever a cult success. You might, therefore, be surprised to learn that it was itself commissioned for proper television. That's right, less than two years after releasing their first episode, Ryan and Rab created a late-night sister show for BBC Scotland called VideoGaiden which ran for three series between 2005 and 2007, then returned briefly in 2016. The content wasn't softened or broadened, either, and the resulting episodes were so much in the same spirit as Consolevania that they can more-or-less be watched as extra instalments of the same, albeit with their own distinct running jokes and characters.

Fittingly, with a budget for guest stars, Rab and Ryan also welcomed fellow cult icons Tim & Eric and none other than Frank Sidebottom himself to the fold. A convention for comedy creators who did things their own way, no matter how much or how little encouragement they received. How on earth does a homemade video game review show get a telly commission, you may now be screaming? Well, remember, this was before the 2008 financial crash, before austerity and before Brexit. A time when our national broadcaster was allowed a little bit of money for making programmes and the occasional, just occasional, commissioning risk could be taken.

Although it may have been late-night and low-budget, VideoGaiden was Robert Florence's first foray into writing and starring in his own BBC Scotland sketch show. His second was Burnistoun with Iain Connell, a more mainstream success that lasted for three series and several specials, and Rab has been a regular writing and performing fixture on Scottish television ever since.

Admittedly, even before Consolevania, as Rab says, "I was already working in TV doing a bit of comedy writing here and there, so the idea of making a 'TV show' didn't feel intimidating." But whether it was Rab's own work or his earlier sketch credits on Chewin' The Fat or Revolver that made the crucial difference, at some point the purse-string-holders let slip a little opportunity to a promising, untested person. Ever since, the results have been varied, compelling and enduring, all the way up to the present day, with Florence most recently seen on telly with his Burnistoun collaborator Iain Connell in their Kardashians-esque family sitcom The Scotts and with fellow Chewin' The Fat alumnus Greg Hemphill in annual sketch round-up Queen Of The New Year.

I'll take any opportunity to bang the drum for sketch comedy and the aching need to open up screen time for newer talent, and there, I just did. Recently, when GamesMaster returned to Channel 4, Rab made for the ideal gaming televisual Scot to echo his precursor Dominik Diamond in the hosting role, resolving another stanza in the epic poem of television history.

Still, alongside VideoGaiden, throughout Burnistoun and GamesMaster and far beyond, Consolevania has continued. Through an evolving video game landscape and a changing roster of core contributors - the arrival and then departure of first Michael S. Hoffs, then Kenny Swanston, then Gerry McLaughlin, then Kenny again - Rab and Ryan have kept the flame burning for twenty years, apart from the occasional eight-year hiatus, but who's counting?

They've learned a lot along the way, as Rab says, "I wish I'd known that we would one day dearly wish we had all the out-takes. We didn't really archive our stuff properly, because we didn't really know any of it mattered at the time." He also wishes they'd reached out more to collaborators, "We always did it all ourselves, and that eventually gave us a bit of stress that was probably unnecessary."

Ryan has learned not to fret about things like blemishless audio recording because "folk'll just say the shoddiness is 'all part of the charm' anyway," and stresses making the most of what you have, "I know now that just about any material can be turned into something in an editing timeline. It might take half a dozen passes at it but as long as you put some time in, there's always a reward at the end. Unlike life."

Since 2017, the show has been released more regularly, funded via its Patreon page. "To be honest, I get so much enjoyment and satisfaction from creating videos that it's quite ideal for me to be in the position of producing stuff every month," says Ryan, "And the fact that there's people that also want to watch the content and help financially support us feels like a total fluke!" Rab puts it more strongly, "The Patreon saved our skins a good few times, without a doubt."

It's satisfying to see that this show, so ahead of its time in the early days of online video distribution, has found a self-sustaining financial model now that the rest of the internet has caught up with it.

Incredibly, the tone and content of the show still feel very familiar. Even though the themes of the show have changed over time along with its hosts' lives, with the boys chucking out more chat about fatherhood, nostalgia and climate dread than going out drinking and chatting up lassies these days, the biographical sketch comedy video game review collage is well and truly intact, and it's just as funny, experimental and unashamedly personal as ever.

With mainstream television so stymied by laser-focused demographic targeting, it's fun to imagine how many notes a single episode of Consolevania would attract from a producer before it hit the airwaves.

- Kids won't remember the Steve Guttenberg film Cocoon.

- Crash-zoom into darts player's face with roaring underneath quite frightening, inappropriate?

- People aren't going to want to spend minutes looking at the title screen for the ZX Spectrum Bullseye tie-in game, cut this down please.

- Accents too hard to understand for international market, find replacements?

Maybe this is what keeps me coming back as a viewer. I heard a story recently that an executive type advised an up-and-coming comedian not to use a noir-inspired segment in their comedy pilot because 'our average viewer doesn't know what film noir is'. Film noir. Trenchcoat, neon sign, gravelly voiceover. I'd wager there are species of algae that live in the deepest crevices of the Mariana Trench that have a working understanding of what film noir is. Even if they don't, maybe I'm deluded, but I genuinely think that people like glimpses into other people's lives, their tastes, their worlds. Not everybody wants all the edges knocked off a show in case they find something momentarily confusing. I recently made a sketch for Crowley Time that was really about a parent being baffled by the popular culture of their child's generation, but hinged on a riff on bizarre Power Rangers knock-off Big Bad Beetleborgs. Most of my listeners got the sketch even though they had no idea what was being parodied, but a few of them did get in touch, thrilled, to ask 'was that a Beetleborgs reference?'

Recently, Rab and Ryan announced the end of the show as we know it, again. But fear not, Consolevaniacs, it has died only to be reborn again, like Christ or Doctor Who. Soon it will become CVXX, "which is Consolevania as a full-on retro show for the next few years," explains Rab. "We've never had a run of purely retro stuff, and as men of advancing years, we think we're well qualified."

The first instalment, coming soon, will be CV84, an episode exclusively covering 1984 in gaming, with each subsequent episode moving one year further on. Says Rab, "It's a show for people who remember those years, for sure, but I know a lot of kids these days are into retro stuff too, so we hope it will be enlightening for them to know who Roland Rat was and understand why Mastertronic was so important for working class kids in the 80s."

They also hope to diversify the industry narrative, "I think we're really keen to do a show that talks about the history of computer games from a UK perspective, because we've definitely seen the perception of game history skew very American in the past couple of decades." There's no end in sight for the show, either, according to Rab, "It would be like stopping writing a diary. It makes no sense to stop now. Consolevania until the grave, at this point. And even then, I'd expect Ryan to review my funeral."

I don't know if I'll still be making Crowley Time after twenty years, but if I am, I hope I'm half as excited about making it as Robert Florence and Ryan Macleod are about Consolevania, and even a third as quick to innovate and adapt. In the current British broadcasting climate, where taking risks is at an all-time low and scripted comedies are being systematically hunted down and exterminated by roving gangs of commissioners, it's never been more important for we faithful ones to build our own platforms and then shout from them as loudly as we can. Fortunately, I had that fire lit under me early in life by a couple of Scottish lads with a camcorder who loved video games and wanted to talk about them in their pants.

You'll forgive me for putting on my wank hat here, but I really believe that back then, it was Consolevania that first showed me that if you make something with love, and have fun doing it, no matter how little it meets perceived audience demands or key demographic trends, your kind of people will find it and they'll love it just as much as you do. And if we can all remember that, and if we can keep enjoying the process, making the most of the resources we have to hand and supporting the independents, then one day maybe, just maybe, Codemasters will finally get what's coming to them. TEAM!

Crowley Time with me, Tom Crowley

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more