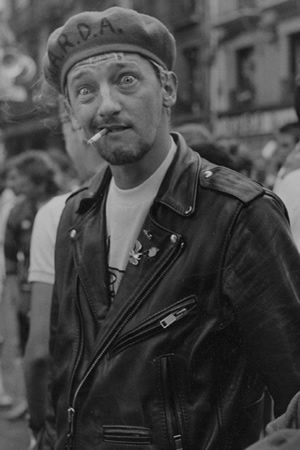

Andy Smart on his first Edinburgh

In this extract from his new book detailing his early adventures, comedy performer Andy Smart talks about the first time he went to the Edinburgh Festival. It's a good tale...

The first time I did the Edinburgh Fringe Festival was in 1980. I hitched up to Edinburgh with a tent and camped at the campsite near the artificial ski slope to the south of the city. It was quite a way out, but I woke up early and caught a bus into town. I had never been to Edinburgh before and was immediately taken by its dramatic beauty. I spent the day wandering round the Royal Mile and the Mound, watching the street shows and listening to those handing out flyers. I didn't have much money, having just returned from Interrailing, so I tried to find free shows. The Fringe club had a late-night bar where if you performed you got in free, so I went along. The room was in the Edinburgh University Student Union - it was loud and it smelled of drunks. I've never been so scared in my life. I was on third after an amateur theatre company that did scenes from its production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, which did not go down well.

I went out onto the stage and took the mike from its stand. I coughed nervously. This seemed to be a sign for the heckling to start. I started telling a joke I'd heard on the TV show The Comedians. When I got to the end, three people laughed and the other 80 upped their game. I could hardly hear myself think. I told my second joke, about a tortoise being mugged by snails. When the police arrive and say, 'Can you describe your assailants?', the tortoise says, 'I don't think so, it all happened so fast.' But by now no one was listening.

I climbed the stairs back to the dressing room. Nobody made eye contact and I felt ashamed and guilty - guilty that I hadn't entertained anyone. I decided that I would never be a stand-up; I'd have to find another way to become an entertainer, but I was hooked. I loved the feeling of the Fringe. Anyone can take a show up to Edinburgh and perform at the Festival - by 2019 I've reached my 40th consecutive Fringe. I love it. I've done street shows, performing as a juggler and with Angelo Abela in The Vicious Boys; I've acted in Twelve Angry Men and The Dumb Waiter; and I've played at the Assembly Rooms, the Gilded Balloon and the Pleasance, as well as lots of other venues. I absolutely love it. I have now spent over two years of my life at Edinburgh Fringe Festivals if you add up all the days.

But that night in my tent was horrible. I was inconsolable. I tossed and turned in my sleeping bag as a light rain began to fall, pattering gently on the side of the tent. I felt wretched and very alone, and I don't think I told another joke to anyone for nearly six months. I had made the classic error of not looking confident - an audience can smell fear and will feed on that fear if they are drunk. Any comic will tell you that there is nothing worse than dying on stage; sometimes it takes two or three days to get over it. Eventually I fell asleep.

The next day I packed up my stuff, left it in the left-luggage office at Waverley Station, and then spent the day exploring the city. I found Rose Street, full of shops, bars and restaurants; I went to the Grassmarket and had a look in the Traverse Theatre. There were people in costume everywhere advertising their shows. At about eight in the evening, I fetched my bag from Lôthe station and caught a bus to the start of the A68 to begin hitching back to Liverpool.

I'd been there for about two hours when two young lads who were going to Selkirk stopped for me. They had been to Edinburgh to see some shows and to hear a band made up of their friends. They had obviously had a great day and I was lifted out of my dark mood by their laughing and chattering.

They told me that I wouldn't get a lift in Selkirk until the morning as the road wasn't that busy, and they asked if I'd like to spend the night at their parents' house. I wasn't sure but they said they lived in a big house with its own stretch of salmon river. They had me. This sounded too good to be true but I was now curious. After an hour's drive we reached Selkirk and stopped at a house on the edge of town. It was only two storeys high but very long. We entered through the kitchen door. There was no sign of their parents. 'They've gone to bed,' said Billy. 'I'll leave them a note.'

He grabbed me a glass of water from the sink and then took me to my room, which was huge. There was a massive double bed with lots of eiderdowns on it, and around the walls were animal skins - a zebra, a leopard and an eland. There were some African masks and a few spears and shields. 'This is the Africa room,' commented Billy, with a big grin. 'Breakfast will be around 8.30. See you then.'

I switched on the bedside light, climbed into bed and read my book, eventually falling asleep at about two. I couldn't believe the difference between the two nights' sleep: one tossing and turning in a damp tent; the next staying in opulent luxury.

I slept well but woke to hear someone going past my door along the creaky oak floorboards. I didn't have a watch and we didn't have mobile phones in those days, so there was no knowing what time it was.

I pulled back the curtains; it was light, a beautiful sunny day. I was looking at a long green field falling away to a bend in a river with a small wood on the other side. It took my breath away, but then I started to panic. I had been brought up properly and knew it would be rude to stay in bed after breakfast had been served. But had I already missed it? I didn't know.

I pulled my jeans on and opened the door a crack. There was no one there. I darted across to the bathroom and washed and made myself look respectable. Then I zipped back to my room, dressed, packed my rucksack and headed downstairs.

As I entered the kitchen I could see a small man in a dressing gown standing at an Aga cooking some bacon. He had his back to me and jumped as I put my rucksack down and it immediately fell over with a crash. To my amazement, when he turned round I realised he was (Lord) David Steel, leader of the Liberal Party.

'You must be the hitch-hiker,' he said casually. 'Billy left me a note. Now what do you want for breakfast? There's eggs, bacon, mushrooms, tomatoes, or porridge if you'd prefer.' 'Um, the fry-up sounds good,' I muttered, still trying to work out what was going on.

Then he cooked me my food and we sat and ate together, discussing Parliament and his party's chances at the next election. It was so surreal. He told me the African trophies in my room had been a gift for sorting out a trade deal. We talked about travelling, unemployment and Thatcher until the other members of the family began to arrive.

His wife was lovely, fussing over me to eat more and asking me about hitch-hiking. Billy and his younger brother and sister arrived, and after breakfast we all went down to the river to see if we could see any salmon running. When we returned to the house to get my bag, Lady Steel had made me some sandwiches. What a marvellous family. I went up to the A7 and headed back to Liverpool.

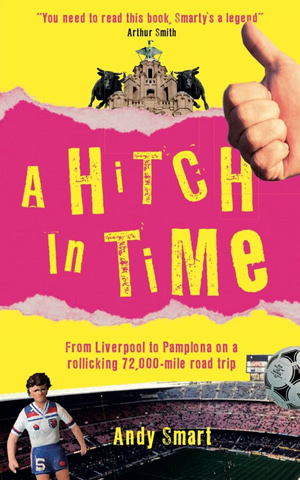

Andy Smart's travel memoir A Hitch in Time (£9.99, by AA Publishing), is out now. Buy from Amazon

Andy Smart: 40 Years at the Edinburgh Fringe is in the Billiard Room at the Gilded Balloon at 1:15pm daily from 31st July to 25th August. Info & Tickets

Help British comedy by becoming a BCG Supporter. Donate and join us in preserving, amplifying and investing in comedy of all forms, from the grass roots up. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more