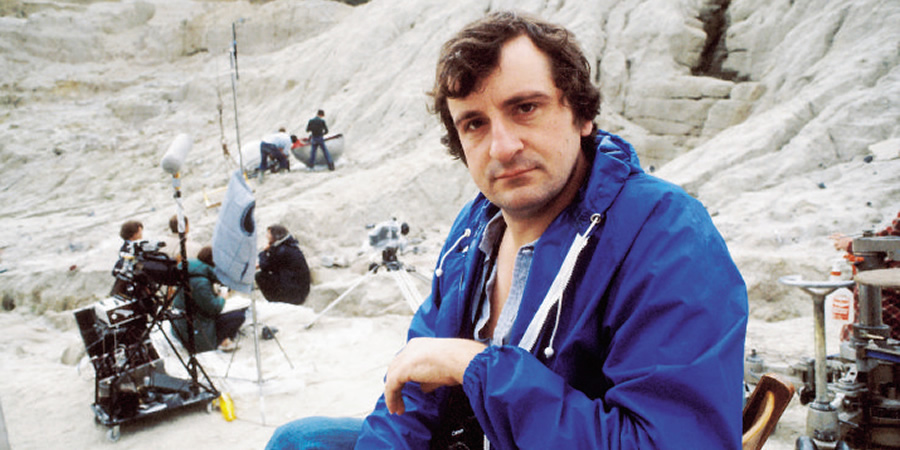

Exploring The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy film - Part 1

The phrase 'development hell' is an over-used one, but when it comes to the film adaptation of The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy there simply isn't a better way to describe the situation. This is the story of the series of delays, set-backs and tragedies (spanning roughly three decades) that prevented Douglas Adams's dreams of a big screen outing for his universally loved tale of Arthur Dent's haphazard travels across the galaxy from becoming a reality.

Adams first began to focus on a film adaptation of his hit novel (adapted from the 1978 Radio 4 series) in the early eighties. As soon as Hitchhiker had established itself as a cult success, Hollywood approached Douglas offering to pay him $50,000 for the rights (roughly the equivalent of $250,000 in today's money) but surprisingly he turned them down fearing that the anonymous producers just wanted to make "Star Wars with jokes".

Although Doctor Who has far more in common with Hitchhiker, the success of the first Star Wars film in 1977 synced up perfectly with the quiet arrival of The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy on Radio 4 in March of the following year.

However popular Doctor Who and indeed Star Trek were before it, Star Wars did become something of a catalyst for a global rethink of the science fiction fantasy genre, and as Star Wars action figures flew off the shelves it was clear that anything to do with space and robots had become extremely lucrative.

Hollywood producers would have clocked that Marvin, the manically depressed robot, would be easy to market as a sort of humorous anecdote to the bright chirpiness of C3PO, but the idea that Hitchhiker's would simply exist as something of a comedic satire in relation to Star Wars (akin to what eventually became the star-studded 1987 Mel Brooks parody of Star Wars, Space Balls) didn't appeal to Douglas. He said he considered agreeing to the deal, but stopped himself: "I suddenly realised that the only reason I was going ahead with it was the money, and that as the sole reason wasn't good enough, although I had to get rather drunk in order to believe that".

Next to throw his hat into the ring was Terry Jones. The Pythons had not only been Douglas's idols throughout his teenage years, they had also become his friends. A chance meeting with John Cleese at the age of 20 became a pivotal moment in Douglas's route to stardom. Adams asked Cleese if he could interview him for Varsity (Cambridge University's student paper); Cleese generously accepted the offer and slowly Douglas was brought into the fold, going on to form close bonds with the entire Python gang.

Douglas was even invited to write the odd sketch for the final series of Flying Circus, popping up in various supporting roles. Yet, when it came to teaming up with Jones to draft a film script for Hitchhiker there was a problem; Douglas was starting to get overworked and perhaps even a little fed up with his own creation. He had adapted the same material again and again (first the radio scripts into a novel, then a TV series, plus a shortened version of the original radio series for an LP alongside a stage play).

Adams now wanted to reinvent Hitchhiker entirely, but these plans failed to gain traction. Ultimately, this had zero effect on their relationship (years later Terry Jones would dig Douglas out of a hole by writing an entire book for him, a novelisation of Adams's last video game project, Starship Titanic) but here the pair called the collaboration off. Jones moved on to co-write the 1986 fantasy epic, Labyrinth, starring David Bowie, produced by George Lucas and co-written and directed by Jim Henson, the genius creator of The Muppets.

Labyrinth offers a glimpse into how Jones might have handled the material. The slightly darker tone of the film was typical of mid-eighties and early nineties family flicks and this approach would certainly have added a new edge to Hitchhiker, which was perhaps something that Douglas ultimately craved.

In the early eighties Adams went to California with his friend, the legendary comedy producer John Lloyd. Whilst there they worked together on The Meaning of Liff, not a novel, but rather a "dictionary of things that there aren't any words for yet". At this point he had fallen seriously in love with the idea of a Hitchhiker film; computer graphics were just starting to be used in film making and perhaps this factor alone was the one reason that Douglas could never let the dream die thereafter. At this time Hitchhiker had only recently arrived on BBC television and how the team managed to realise this feat is still a bigger mystery than the ultimate question.

The Hitchhiker TV series was a three hour long science fiction epic produced on a shoestring budget in the early eighties that still manages to impress. The series was instrumental in carving a visual brand for Hitchhiker that carried through every adaptation thereafter. If anyone pitched the same idea to the BBC today, it would be deemed impossible without millions of pounds of investment from other production companies. Yet, despite the TV show's success, Douglas was never fully sold on the adaptation produced by Alan J. W. Bell, and perhaps one of the reasons why, was that it just couldn't look real enough for him... it didn't live up to his limitless imagination. Slartibartfast introducing us to the factory floor of Magrathea could never be that mind-blowing using just set pieces alone, with computer graphics a sight majestic enough to take Arthur's breath away could, and eventually would be achieved.

By the mid-eighties Douglas had become so serious about turning The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy into a movie that he spent a year in Los Angles working with future Ghostbusters director Ivan Reitman.

Adams signed a deal to have Reitman produce the film alongside Joe Medjuck and Michael C Gross. He completed three scripts which were all rejected. It was alleged that Reitman was never really convinced by the Hitchhiker brand in the first place. Infamously, it has been said that Reitman found '42' as the answer to life, the universe and everything a bit "disappointing". However, this has been deemed a misquote, as apparently, he just didn't want the revelation of '42' as the ultimate answer to be revealed at the finale of the film, feeling that this fact alone would have been the "disappointing" element.

Ultimately, these disagreements would seem to be for the birds. Douglas needed the kind of spirit and belief that brought Monty Python And The Holy Grail to the big screen. Whether the revelation of '42' came at the beginning, middle or end had become irrelevant, it was clear that he was never going to be able to draft a script that worked for everybody involved.

Years later, Adams saw the funny side of his situation. Cheerily talking with Clive Anderson on his chat show (before launching into a three-minute explanation of the mating rituals of the Kākāpō) he said, apparently referring to Reitman:

"I thought, here is a guy who has just bought two gallons of chocolate chip ice-cream and is complaining about all the little black lumps in it."

Although this may sound a bit barbed from Douglas, it's worth bearing in mind some of the notes that he was getting back on his scripts: 'Dialogue in Scene 94 is bad' and 'on Page 116 we're introduced to yet another character: Slartibartfast, a funny old guy who builds fjords. I think he is an enjoyable character, but his inclusion in this piece is totally arbitrary. He comes from nowhere, disappears suddenly and has no reason for being, except to impart some third-person background narrative.'

It is also worth noting that throughout this period Medjuck and Gross became interested in bringing in Dan Aykroyd to play Ford Prefect. On the basis of this offer, Aykroyd pitched another idea directly to Reitman, his very own science fiction fantasy epic that he'd been trying to get off the ground for years. You've guessed it... this was the origin of Ghostbusters.

Meanwhile, Douglas had already signed a contract with Reitman at Columbia Pictures, which left him now unable to back out of his deal with the trio. Although they had once made a valiant effort to get Hitchhiker into production, and no doubt felt that they had given Douglas a fair crack at the whip, they were all now busy working on Ghostbusters.

Falling into a kind of depression, Douglas returned to the UK to write his fourth novel, So Long and Thanks for all the Fish. He said of that period, "I had a slight case of farlem - the feeling you get at four in the afternoon when you haven't got enough done".

There was a reason Douglas was feeling farlem. The conditions under which he wrote his fourth novel have become notorious. In short, Douglas was so exhausted that he just couldn't write the book. The final deadline came and went, but the novel still hadn't been written. So, the editorial director of Pan Books, Sonny Mehta declared, 'I'm going to get a hotel room and I'll move in myself and make Douglas churn out pages.'. An extended stay at a hotel, with Douglas locked up and forced to write the book ensued. Menta acknowledged that the whole situation was 'macabre', admitting giving Douglas a day-to-day schedule.

This wasn't even the first time this sort of thing had happened to Douglas Adams, a similar situation occurred during his tenure as script editor for Doctor Who in 1979. Adams wrote one of Tom Baker's most famous adventures, The City of Death, under extreme duress. Together, producer Graham Williams and Douglas Adams had found themselves a script short after one of the writers in the team had to drop out for personal reasons. Douglas recalled exactly what Graham had said to him upon realising this, 'You're going to have to write a script... a four-episode script... So, he took me back to his house, locked me in his study... um, and basically hosed me down with whiskey and black coffee for the weekend'.

Michael Hayes, the director of the Doctor Who serial, confirmed this account: 'That is exactly what happened that weekend in Richmond. I think it was really, basically over the Saturday night and I can absolutely vouch for the fact that they drank gallons of black coffee because it was me that made it!'.

This was the true genius of Adams on display, under immense pressure, he could turn out a story that is often regarded as one of the best Doctor Who serials of all-time. On the fly, he could dash off something magical and unique.

In the case of the novel So Long and Thanks for all the Fish he created a charming romance between Arthur Dent and a mysterious girl, Fenchurch. This new direction for Hitchhiker caused a bit of a stir, but it is the closest the source material got to the eventual plot of the film. With romance and flying in abundance, Douglas had moved to give Hitchhiker a more Disney-style appeal. It was less Labyrinth and more Peter Pan, by no means a bad thing. But what with Hitchhiker constantly changing all the time, everybody (Douglas Adams included) seemed less confident as to what exactly the film adaptation should be striving for. He said of his attempts to write a tight script:

"The material just doesn't want to be organised... Hitchhiker's by its very nature has always been twisty and turny, and going off in every direction. A film demands a shape and discipline that the material just isn't inclined to fit into."

No one can really settle the great debate, 'what is the definitive version of Hitchhiker?'. Millions say it's the book, but thousands more prefer the original radio series, whilst others first experienced the story via the 1981 TV series. Here in lies the problem, everybody wants and expects something different from The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy.

The mid-eighties saw Douglas reinvent Hitchhiker as a video game. It was a revolutionary idea and quickly became a sensation, becoming a best-seller in the US. This presumably reignited interest from Hollywood as the only Hitchhiker film script that has leaked into the public domain came about a few years later, the 1987 draft co-written with another industry writer.

To say that it's a much-maligned script would be something of an understatement. It seems mean-spirited to lay blame squarely at the co-writer's door, we can't possibly know who was responsible for which edit, but this may just have been a simple case of the two writers being incompatible with each other. One of the most famous howlers was the re-working of the classic, 'time is an illusion, lunchtime doubly-so' line. It ended up as:

'Time is an illusion, especially lunch-time.'

The ending saw Arthur return to Zaphod's ship, The Heart of Gold. He chose a life of galactic exploration over a chance to stay on his home planet. Instead, he reunites with Ford, Trillian, Zaphod and Marvin, who, for some reason, in this version is not only a manically depressed robot, but a drinks fridge.

It's hard to judge this script, because it is, at the end of the day, a rough draft of an unmade film. However, it did seem to shape the ending for our 2005 Hitchhiker movie, so, it is relevant.

The nineties saw Douglas in limbo with his Hitchhiker film pitch once again. At one point Michael Nesmith (of The Monkees) became involved, but their collaboration failed to move anything forwards. 1997 was the turning point, the success of Men In Black at the box office had made science-fiction comedy seem attractive to investors. Douglas twigged that he may finally be on the cusp of his dreams, but it was always tough going and at times he seemed to give up on the idea... but never entirely.

At one point he wanted to concentrate on a Dirk Gently movie script instead, inspired by a stage production of the first Dirk Gently novel starring Rory Kinnear, and perhaps also the success of the supernatural blockbuster Ghost which bore more than a passing resemblance to the plot of Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency. Yet, whichever way he turned Douglas was finding himself continually "ghosted" by Hollywood.

As the nineties came to a close nothing was continuing to happen. Douglas teamed up with his good friend and business partner, Robbie Stamp, and together they secured backing from Caravan Pictures, a small production company that managed to achieve the seemingly impossible, they brought in Disney.

Jay Roach (director of Austin Powers) began working on the project with Touchstone Pictures (a subsidiary of Disney). Things were at last moving forward - despite delays which inexplicably saw a non-Adams authored script doing the rounds. When Douglas was finally brought back, he eventually produced a script which the entire team could all agree upon. Still, Disney were seemingly unhappy, they put the project into 'turnaround' - a term used to essentially throw scripts into the long grass. It was more bad news for Douglas. The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy film was trapped once again.

At the turn of the century, when it finally looked as though Jay Roach had managed to reignite interest in the script, Douglas moved to America with his family in a bid to make the film happen once and for all. And then, one morning, feeling in good spirits and positive about the future, Douglas Adams died suddenly of a heart attack aged just 49. He left fans shocked and bereaved the world over. Sometimes the universe seems an unbearably cruel place.

Immediately after Adams's death there was a huge surge of interest in all things Douglas. There were re-issues of all the books, whilst the beautiful continuation of the radio series began on Radio 4 after an almost twenty-five-year hiatus. And, although arguably the most faithful and glorious adaptation of Adams's work there has ever been is the third radio series (broadcast in 2004 and known as The Tertiary Phase), the main event for most fans was still the movie. It was the one thing Douglas had always wanted and often prioritised above all else.

After the initial devastation of his passing, there was a feeling as though a phoenix had risen from the ashes; not only was the world now ready to re-evaluate Douglas Adams as a classic author, it was now universally felt that he was posthumously owed his film.

It was decided by his widow, Jane Belson, that the movie project would continue to move forwards. Robbie Stamp picked up the baton and ran with it, whilst Jay Roach brought in screenwriter, Karey Kirkpatrick to draft a script based on all of Douglas's previous efforts.

It was an unenviable task but, following a brief rejigging of production roles (Roach stepped down as director and was replaced by Garth Jennings), on the 19th of April 2004 cameras finally starting rolling on The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy.

Robbie Stamp recalled: "It was a great moment and it did bring a tear to my eye. I was proud that we'd got to that point, but so sad that Douglas wasn't there to share it."

Next time we'll take a fresh look at the resulting film...

Continue reading: Exploring The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy film - Part 2

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more