Making Stan & Ollie

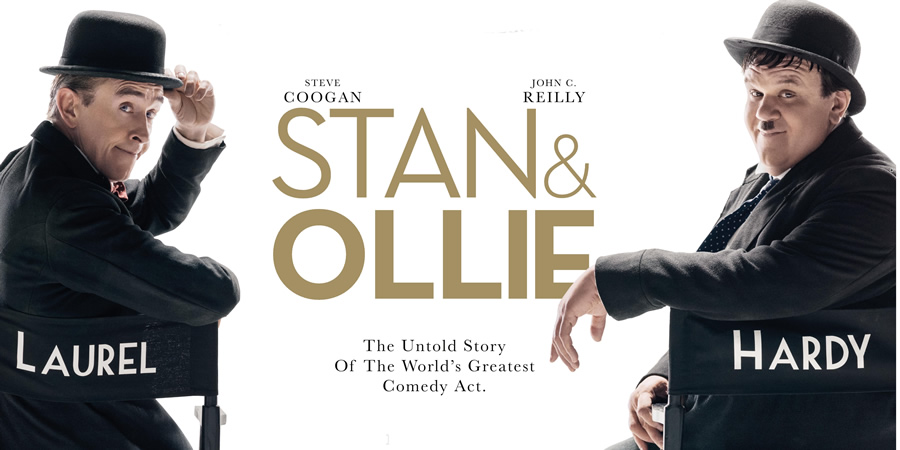

An in-depth feature in which the cast and crew of Stan & Ollie explain how they brought Laurel & Hardy's story to the big screen.

Writing Stan & Ollie

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy are widely regarded as the greatest comedy partnership in movie history. Between 1927 and 1950, they made over 107 film appearances (32 silent short films, 40 sound shorts, 23 features, 12 cameos), defining the notion of the double act with infectious chemistry and humourous routines that seemed effortless but were honed down to the finest detail. The pair were part of the very few silent stars to survive and thrive in the sound era, adding wordplay to their comedy mastery, "You can lead a horse to water but a pencil must be led," quips Stan in Brats.

Their influence goes way beyond cold stats and film buff analysis having amassed a huge and devoted international fan base, three museums and an appreciation society, Sons Of The Desert. Beloved the world over - in Germany, they are Dick Und Doof, in Poland Flip I Flap, in Brazil O Gordo e o Magro - they are a gateway to comedy, a passport to a world of sublime silliness and everlasting friendship. Whether you know them from TV reruns, cartoon adaptations or a Twitter gif, just to hear their theme tune, The Cuckoo Song, is not only a guaranteed smile, it's a time machine to a more innocent age. People admire Charlie Chaplin, sit in awe of Buster Keaton but they love Laurel & Hardy. There is a hardly a comedian alive who hasn't been influenced by Laurel & Hardy, their reach is long.

It is an affection shared by Stan & Ollie screenwriter Jeff Pope. Weaned on Saturday morning BBC TV screenings of the pair's legendary two-reelers, Pope was gifted a Laurel & Hardy DVD box-set fifteen years ago, watched Way Out West and started to investigate the story behind the icons. His research revealed a little-known slice of Laurel & Hardy history: the double act's theatre tour of the UK during the early '50s as documented in AJ Marriot's book Laurel & Hardy: The British Tours.

"You just have this wonderful picture of these two guys that had been such giants staying at little guest houses, playing tiny theatres and not realising they did it because they loved each other," says Pope. "This is the thing that inspired me to write the whole film. It's a love story between two men."

Producer Faye Ward agrees with Pope, saying "Stan & Ollie is essentially about two best friends. And what that means to be two best friends at the end of your life, without them being aware about the end of their life. But it's also about these two creative forces and how that magic arrives"

Steve Coogan who plays Laurel and worked with Pope on the Academy Award nominated screenplay for Philomena immediately responded to Pope's approach of analysing their 35-year relationship through the prism of the tour.

"It is very smart of Jeff to do that because the mistake is often to try and do a biography where you tell the chronological story of someone's life," he says. "It's better to shine a light on a specific aspect of their lives and you can learn everything from that. You can see humanity in a moment."

The filmmakers decided to call the film Stan & Ollie, not Laurel & Hardy as the production was dedicated to exploring the men behind the legends, Pope's script revealing truths behind their cinematic personas. Whereas Hardy would often take control on-screen, Laurel was the creative brains who oversaw every aspect of production; once shooting had finished, Hardy would often go off and play golf. The film also suggests that, while in the movies the pair were inseparable, off-screen they were friendly but just work colleagues. As Pope puts it, "They were never really close until they took these arduous tours and they lived in each other's pockets week in, week out. The premise of the film is how they became as close in their real lives as they were in their fictional lives."

Producer Faye Ward explains: "I think it was really important this idea of getting back to the homage and essence of Laurel & Hardy and the reason why we didn't want to do a conventional biopic. We wanted to create something that new and old audiences could enjoy. Laurel & Hardy have huge fans around the world, as well as huge comic fans like Ricky Gervais and Paul Merton, John C Reilly and Steve Coogan there are millions of others, thousands of people talking about how inspired they still are by them. I think there's an immediate ease even if you're new to them you can feel the inspiration of what that comedy duo did for the comedy we still see today."

Pope's script is peppered with telling, touching details about the central relationship - Laurel kept writing sketches for the pair seven years after they had retired - yet Coogan was constantly aware Stan & Ollie needed other colours. "I knew the film was going to be poignant and sad and emotional, my fear was: would it be funny enough?" he says. "You have to earn the right to have the poignancy by charming people. You can charm an audience with comedy."

While much of the comedy comes from meticulous recreations of the duo's stage acts, Pope's script also sews in some of their most famous routines into the fabric of their lives. So their attempts to get the trunk up the stairs in a railway station closely mirrors the memorable piano-stairs sequence of Oscar winning The Music Box. "As the script evolved, I realised there were certain points I could tip my hat to their glorious past," says Pope.

But for Coogan, stitching their skits into everyday situations also says something about the nature of comedians. "As with many comics, there is not a total distinction between a comedy character an actor plays and who they are in reality, especially if they are heavily involved in the creative process," he observes. "There is an overlap and we try to let the audience see that, really if you are a Laurel & Hardy fan, then I think we honour the memory of them for those people for whom it's important that we don't generalise and that we are specific, and that we're faithful to who they were. And for those who aren't, it's entertaining because when we re-create some of their iconic moments I think we do it in such a way that it's funny and it still makes people laugh now."

Realising Stan & Ollie

Jeff Pope sent the script to Jon S. Baird, who was directing Danny Boyle's TV series Babylon. Baird, who remembers watching Laurel & Hardy growing up in Scotland had a background in recreating the comedy legends. "I've still got pictures of me and a pal dressed up as Laurel & Hardy in a school fancy dress show," he laughs. "I was Stan, he was Ollie. He had a lot of padding, the first remnants of a fat suit."

The film's journey to the big screen really stepped up when Fable Pictures' producer Faye Ward joined the team. Ward had met Baird on film industry initiative Inside Pictures and she immediately recognised the story had a chance to appeal beyond a film buff fan base.

"Even if the film wasn't about Laurel & Hardy, it's about two best friends who have lived through something together," says Ward. "They lived through wives, work, bankruptcy, highs and lows. They are reaching a point where they are realising they are old and might be towards the end of their lives. Watching that reflection would be fascinating even if they weren't Laurel & Hardy. It was incredibly clear to me when I first read Jeff's script and heard Jon's vision I could see the potential of how special the movie could be."

With family near Stan Laurel's hometown of Ulverston, Ward spent many summer holidays at the Laurel & Hardy museum. A big fan, she brought a passionate zeal to ensure Stan & Ollie didn't fall into the spoon-feeding clichés of true life stories.

The director had a clear take on the compelling dramatic question raised by Ollie's decision to make a film, Zenobia, without Stan. "It's about a marriage between these two people who love each other but someone has committed an infidelity in the past," he says. "Then the other one has the opportunity to do the same: do they take it?"

Just before shooting began, Baird was struck by appendicitis and had an emergency operation but he made an almost miraculous recovery and was back on set in a week. As the production moved forward, the clarity and confidence Baird brought to the project impressed everyone. "Jon was fantastic on set, really specific and clear with his direction," observes Coogan. "There was no waffle, which sometimes you get from directors."

John C. Reilly, who plays Oliver Hardy, was similarly taken with Baird's passion. "Jon is the person who sat down with me and made me feel I could really do it. He was a true believer, a very unflappable optimistic guy. If we have any success with this project, it will be with Jon's commitment to the project and belief in us."

Ward says of working with Jon: "He is incredible, he's got such a vision for the piece and I felt he really got under the skin of Laurel & Hardy and Stan & Ollie."

Baird's cinematic dynamism is present from the get-go. The film opens with a six-minute tracking shot that follows Stan and Ollie from their dressing room across a Hollywood studio lot, onto set and into an argument with studio boss Hal Roach.

"I just felt to get that flavour of Hollywood, it seemed like the right device," notes Baird. "You need to see it unfold all the way through. I thought the script really called out for it. I wanted to challenge myself as well."

Baird's bravura asked a lot not only of his crew but also of his actors, who had to deliver reams of dialogue in one go. "There is a lot of pressure in a shot like that," admits Coogan. "You almost have to not care about it. If we were on tenterhooks about screwing up, the casualness would be too inauthentic. So you forget about all the choreography, you just think we are two guys having a conversation. I think that comes with experience, realising the best thing you can do is just relax and stop giving so much of a shit about everything."

The shot immediately leads into another pressurised and iconic moment for the actors: Stan and Ollie's iconic dance to At The Ball, That's All in front of a Saloon backdrop in the classic Way Out West. Coogan and Reilly worked with Director Of Movement And Choreography Toby Sedgwick to get the scene down perfectly. The dance makes a number of appearances in the movie as Laurel & Hardy perform it on tour, with the routine getting increasingly creaky. For the on-set version, Sedgwick even coached the actors to incorporate the mistakes the stars made during the filming.

"We choreographed that dance so many times we could do it in our sleep" confirms Coogan. "What's great about watching them dance is that they are just sort of throwing it away and not appearing to try very hard. It requires a lot of work to make something look easy."

Ward elaborates on the extraordinary dedication Coogan and Reilly showed: "It was amazing the level of work John and Steve had put in. They'd replicated in so much detail that even when the real Laurel & Hardy in the footage get it wrong, they'd recreated the mistakes too; they got it absolutely spot on and it is magic to watch."

As well as the dance, Sedgwick, an expert in clowning, also worked with the actors to create the skits Laurel & Hardy performed on stage. Sedgwick, Coogan and Reilly built the established routines from the ground up but also invented new shtick especially for the film. For the actors it added an extra dimension to the filming.

"We had to forge a bond in those moments because it wasn't just a film," recalls Reilly. "Because of the theatrical nature of the tour we were filming performances with people out in front of us. It was not only the pressure of making a film but then there's the pressure of all these people sitting there watching us. We've got to deliver for them too. It almost gives you a battlefield loyalty to each other. I'll always love Steve for what we went through together."

Casting Stan & Ollie

Key to the success of the film was finding actors who could not only inhabit but also illuminate the inner lives of the central partnership, to shine a light on whom the men actually were, what made them tick.

Steve Coogan was the first and last person Jon Baird spoke to about playing Stan Laurel. Coogan first saw Laurel & Hardy on TV, watching their misadventures in a dressing gown during school summer holidays. "It was very accessible to a child," he recalls. "A pure kind of comedy that is to do with character not situation. There are no real consequences. It's a happy world."

During Skype meetings with Baird and Ward, Coogan would effortlessly slip into Laurel's mannerisms but his performance also captures the drive and decency of the man. As Ward puts it, "I think it's great to see Steve do something you've not quite seen him do before."

Baird elaborates "I met Steve over lunch one afternoon and we were chatting away about Stan Laurel, and without any warning he went into Stan, he started doing Stan. And he would drop his napkin and then come up and bump his head on the table and the shivers went up my spine and I thought 'wow', and it was just that little moment, it was everything. I knew he was a very clever guy and I knew that he would absolutely get everything that it was supposed to be but actually bringing Stan off the page, in the amount of detail he puts into the voice and the performance, it was just a no brainer after about five minutes of speaking to Steve about it. Everyone got excited when Steve got involved, for obvious reasons."

"I had a great partner in Steve," says John C. Reilly. "We realised from the beginning there's no way to do this unless we learned to love each other. We were pretty much strangers but we became real friends. He is one of the funniest people I have ever met. I'd get this real lonely feeling whenever Steve wasn't on the set with me, it would feel like a part of me was missing."

Faye Ward recalls how she felt when Coogan and Reilly were onboard: "It was just so exciting to get John and Steve, there're really not many actors in the world who could actually be Laurel and Hardy, they're just incredibly tuned comedians with a perfect sense of physical comedy timing. It was just so wonderful to see those two play Laurel and Hardy, you did feel like you were watching two icons playing two icons."

If Coogan's career has been marked as a solo performer, Reilly has worked in partnerships with the likes of Will Ferrell. But still the actor was daunted at the prospect of playing a comedy legend. "In a way I tried to talk my way out of the project because it was so overwhelming and intimidating to play these guys," says Reilly. "I feel we live in an age of Google and Wikipedia and anything that anyone wants to know about the facts of someone's life are instantly available. But the beautiful thing about this story was you go inside their relationship and it gives you a glimpse of what it might have been like working together."

From comedies to musicals to drama, Reilly's range was critical in landing the screenplay's balance of laughs and emotion. "He's a fantastic actor," says Coogan. "He is also able to be mature, poignant and truthful and at the same time have an understanding of comic technique. They are two different skill-sets. Comedy is frequently a technical skill and being emotionally open and honest is about being in touch with your feelings. There isn't a huge amount of actors who can do both those things. He is one of them."

Reilly's casting was also instrumental in landing Coogan. "I asked whom were they thinking for Oliver Hardy," Coogan recalls about his early discussions for the role. "They said they were thinking of John C. Reilly and I said, 'Well if you get him, I am in.'"

Baird recalls his meeting with Reilly. "The thing John said was 'it's a massive responsibility to play this character, he's my hero', and Steve had said that as well. But John said 'I can't let anybody else play this part, it's terrifying to take this on but I can't let anybody else do it'. And I thought 'well, if that's the kind of guy you are, that's the kind of guy I want to work with because it shows responsibility, it shows bravery."

Once both men signaled interest, the team had to check the chemistry vital in bringing the relationship alive. "Jon and Jeff flew out to New York to put them together to make sure they got on," remembers Ward. "It was totally nerve-wracking. They left them to it in the restaurant and then suddenly in the distance they saw Laurel & Hardy sitting having dinner. It was just like 'They are the ones'."

And that magical combination was felt throughout the shoot, Ward recalls "When they first did the live theatre of Double Doors, it was in our first week of shoot and in front the whole crew - film crews can be somewhat cynical because they see hundreds of movie stars do a million things; but the whole place fell completely silent in awe and then laughing hysterically. And in fact Harriet who is our second AD was crying, it was just that amazing."

One the most difficult scenes the actors had to perfect was the Way Out West dance. Steve Coogan remembers: "We had to study what Laurel & Hardy had done on film and then rehearse it and choreograph it, but what was peculiar was that we had to not only learn these dance steps, but the way they performed them was slightly haphazard and almost deliberately has a kind of amateurish charm and there are mistakes in the way they dance, and we had to learn the dance - with their mistakes. We had to emulate every misstep they made and every throw away gesture, that was quite hard as we had to learn to emulate what was in the original film and we had to perform the same dance routine on stage, but without the errors. So you have to learn the dance two ways: one way with some slight, odd errors and another way which is more refined. So it got quite confusing but we did it so many times that we just knew it, I could probably do it now!"

The Wives of Stan & Ollie

In the fictional world of Laurel & Hardy, the pair's wives are sometimes portrayed as henpecking their hapless men into submission often resulting in a madcap scheme. Stan & Ollie's conception of Lucille Hardy and Ida Laurel playfully nods to the notion of nagging wives whilst simultaneously painting a much more rounded portrayal of two very different women who were the bedrock for their partners amid the ups and downs of showbusiness. These women were strong, intelligent and forthright and we are left in no doubt that these iconic men absolutely needed the women they had standing behind them.

As Ward says: "The wives come along and they're also a duo. What Jeff has achieved so cleverly in the script with Ida and Lucille is that you don't know a huge amount about their history together with the men, as well as their careers, but he shows you enough so that you can understand that they have gone on a journey for a long time with these men and they have their own quirks and energy together - they are their own double act."

Both Coogan and Reilly had input into who played their spouses. Although Shirley Henderson had previously worked with Baird twice, it was Reilly who suggested her to play Lucille, the Way Ouy West script supervisor who became Hardy's third wife, after working with her on Tale Of Tales. Given Lucille was a Texan and Henderson is Scottish, Reilly and Baird had to convince the production she was right for the role but, for the actor, the advocacy was completely worth it. "As an actor, as I was playing bigger, older and with bad knees, I had to believe the person playing my wife not only loved me but was attracted to me," he says. "Shirley and I developed a real affection for each other."

Despite having worked with actor and director before, Henderson recalls, "it wasn't an easy job to get. I had to do three auditions!" Having fond memories of watching Laurel & Hardy on Christmas morning, Henderson reacted to the dilemma in Lucille's love for Hardy during the punishing tour.

"She is concerned he is taking far too much out of himself but acknowledges he needs it for his life-blood. She cares very deeply for him. And that's what I latched onto. No matter what, everything was about him, his health and his well-being."

If Lucille is quiet and undemonstrative, Laurel's wife Ida, played by Nina Arianda, is a tour de force with a flair for the dramatic. Arianda caught Baird's eye following her role in Florence Foster Jenkins. "I think she is one of the best actors I have ever worked with," says Baird. "It was a total mixture of what we were looking for: somebody who was quirky but had that sense of tough love which is kind of an Eastern European sensibility. She was perfect."

A Tony award-winning actor, Arianda was drawn to the story's exploration of "the public vs. the personal." A dancer in Hollywood, Ida understood Stan's creative ambitions and his need to be "on." Yet beneath her histrionics, there was an empathy and vulnerability that Arianda found engaging.

"I thought she was wonderful in both her warmth and strength," she says. "I loved that she adored this man so deeply. The thing that struck me in doing research was that the first thing that attracted her to him was his loneliness. I thought it was a very specific woman who was attracted to a man's loneliness. I found that fascinating."

Ward recalls "Shirley and Nina both spent so much work researching the real wives It was incredible to work with Nina and Shirley they are also both such fantastic heavyweights and we were just so fortunate to have them in the roles."

The arrival of the two women in London is when, according to Baird, "events start hotting up. Things are brought up from the past. They are the catalyst for the argument that leads to the split."

The Money Men of Stan & Ollie

Key to the break-up of Laurel & Hardy was their longtime collaborator, producer Hal Roach, played by Danny Huston. The actor spent some of his childhood in Italy so only knew the comedy duo as Stanlio e Ollio dubbed into Italian. "I remember coming to London as a child and being horrified that they were speaking in English," he laughs. Huston plays the hard-nosed Roach as a "cigar-chewing studio boss" refusing to pay the pair what they are clearly worth, pitching the performance between broad comedy and something more realistic. Yet for all the potentially cartoonish qualities of the character, he is quick to acknowledge Roach's importance in the Laurel & Hardy story.

"You could also say he discovered them," says Huston. "They were both independently successful as actors but he had the genius of putting them together. I use the word 'genius' lightly because they were the geniuses but he was able to capitalise on them. He had a keen enough eye to know they would be a triumph together."

"There is nobody who knows Hollywood like Danny Huston," says Baird. "He's steeped in it. He's a very handsome guy and we wanted him to be that very commanding studio head. He told us some incredible tales about his dad, John Huston, and some of the stuff that was going on then. He was great to have around as a reference for that time period."

"Hal Roach is only in the film a small amount" Faye Ward says "what we needed from the Roach character was a 'super injection' of Hollywood, so to speak, we are depicting old Hollywood in its purest form so who else to ask but an actor with Hollywood running through his veins - Danny Huston. When he arrived on set he simply had this aura of 'Huston' to him, which oozes Hollywood mogul. He was perfect."

She continues "Physically there had to be an element of somebody who seemed scary to John C Reilly and Steve Coogan, and there's not many people in the world that has that texture, that gravitas that you feel like this gentlemen could hire and fire these two icons in a second. Danny has that in spades."

A kind of British theatrical version of Roach, Bernard Delfont is the impresario who brought Laurel & Hardy for a UK tour in the 50s. As played by Rufus Jones, Delfont is an archetypal showbiz schmoozer. "He'll never stab you in the back but he might deliver live acupuncture," laughs Jones. "He's two cups Bob Monkhouse, one cup Denholm Elliott in Raiders Of The Lost Ark and a dash of Ian Faith from Spinal Tap. He's very urbane, very charming."

Faye Ward describes Jones' energy on set "Rufus brings this modern, youthful energy into Delfont. It is 1953 and far into the career of these two men and it is a joy to watch him standing next to these giants of comedy with this youthful energy. Delfont enters their lives, he understands television, he understands the modernity of life. Laurel & Hardy haven't yet reached that point. Plus Rufus is very, very funny and extremely likeable which is so key with Delfont."

As a kid, Jones was a self proclaimed "Laurel & Hardy completist nerd" joining the fan club Sons of the Desert and buying Super-8 two-reelers to project against his bedroom wall. Such an important pillar of his childhood - "Laurel & Hardy were my girls and booze before I could afford girls and booze." - Jones was nervous picking up Jeff Pope's script as a super-fan. Flicking through the pages, he breathed a sigh of relief.

"I think Jeff did a fabulous job of giving you everything you wanted to see in terms of the iconic Laurel & Hardy scenes with such really delicious references to their work but at the same time presenting Stan and Ollie as opposed to Laurel and Hardy and realising them as three dimensional characters."

Becoming Stan & Ollie

Coogan and Reilly's physical transformation was overseen by make-up supervisor Jeremy Woodhead and Mark Coulier, the talented prosthetics designer who won Academy Awards for The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Iron Lady.

"Mark Coulier is an absolute genius" said Producer Faye Ward. "The level of work that went into perfecting the look for the two boys was unbelievable and having talent like Mark onboard and working alongside Jeremy just elevated the whole process."

After lots of experimentation, the team made the decision to dial back the make-up for a less is more approach. "You have to be very careful the viewer isn't thinking, 'What incredible make-up!'" explains Coogan. "They have to get lost in the performance, in the story. So we didn't want anything too distracting."

"It's not a waxwork," says Woodhead of the prosthetic. "You've got to design it in a way they can move, talk, perform and do all these things. It's not a carbon copy but it's as near as we can get it to enable the actors to do their bit."

In the end, Coogan opted for a false chin, teeth and customized tips to make his ears stick out. In a strange coincidence, Coogan has brown eyes and needed blue and Reilly had blue eyes and needed brown so both men wore coloured contact lenses. For Stan's hair, raised in a quirky quaff on screen, Woodhead stuck to the back-to-basics philosophy: "Steve uses his own hair but it is coloured to match Stan Laurel's," he says. "Stan was actually a red-head. We toyed with the idea of going red but it gets distracting - it becomes a surprise that his hair was red. By the end of his life, he was colouring his hair anyway."

To become Ollie, Reilly endured four hours in the make-up chair. By the 50s, Hardy weighed near 400lb but the team took the decision not to go that heavy. Coulier and Woodhead tried four different fat suits made out of reticulated foam. To get the look right, the team drew inspiration from Hardy's own life.

Ward says "We worked for a long time with John C Reilly to get his look right, he came in and did 100s of different sessions and we built his suit in many different ways. And of course there are a huge amount of practicalities in regards to prosthetics because not only do you have to look the part but you have to be able to act through it, you have to be able to feel the magic of John C Reilly through the suit but be perceived as Hardy."

"Oliver Hardy's nickname was 'Babe' because he had the shape and proportions of an overgrown baby," says Reilly. "I started sending baby pictures to Guy and Mark and it started to click."

Reilly had different suits for the various stages in Hardy's life, the 1937 version more firm and controlled. Although reticulated foam is lightweight, it still retained the heat so Reilly was plugged into an ice machine in between takes. The whole process was helpful for Reilly to increase his confidence to play the character.

"Only my face and the flats of my hands were exposed," he recalls. "The rest was encased in prosthetics or a fat suit. So in a way it was like wearing a mask on your whole body. The mask was so convincing it made me believe from the outside in that I could play this character."

Shirley Henderson recalls the first time she saw Coogan and Reilly in full costume and make up "It was just mind-blowing. I saw them first on the Blue Ridge Mountains song, you know when he knocks him over the head with a hammer and everything. Nina and I were in the back of the auditorium, our characters are meant to be sitting, later on we're meant to be sneakily watching what they're up to. But all day we were just sitting there watching them perform this, and it was... it was like it was Laurel & Hardy, it was phenomenal. That they could just do that. There's obviously little hints in their faces, but the prosthetics and the voice and the dancing, it was just immaculate, incredible to watch.

Jon Baird remembers the first time he saw them. "There was complete silence," he recalls. "I thought there was something wrong. But there wasn't. People were just astounded by how they looked."

Nina Arianda got her first glimpse of the pair shooting a scene where Ida watches them perform. "I forgot where I was for a moment," she marvels. "I felt like I was watching Laurel & Hardy. In that room I can't tell you how magical it was. On that day I completely forgot what I was doing."

Dressing Stan & Ollie

For Stan & Ollie, costume designer Guy Speranza and his team created just under 2000 costumes to represent both 30s Hollywood and 50s Britain. But there were two elements that took absolute precedence - the hats and suits that form the unmistakeable and iconic silhouette of Laurel and Hardy.

"Poor Guy," says John C. Reilly. "He must have manufactured 20 different types of bowler hat to get the height of the crown or the width of the brim just right because we couldn't afford to get that wrong. The image is so iconic."

Speranza's research ensured no detail went unnoticed. Laurel would unstitch the brim of his hat - a cross between a bowler and a derby - then cut the brim and re-stitch it to give it the appearance of being much taller and thinner. Speranza fashioned a dark suit with a Norfolk fabric for Ollie, who wore the jacket with one button done up to accentuate his stomach. The designer put Laurel in a light three-piece suit with lots of pockets with shoes without a heel - Laurel would remove the heels from his shoes to give him a comedy gait which meant the trousers were too long. Speranza was also keen to demonstrate the distinction between fictional and real-life appearances.

"On stage, Stan in particular was scruffy," he observes. "Ollie was the smarter one. In real life they were quite dapper. The biggest thing was trying to give an American feel to their costume because their fabrics were much nicer. There's lots of images of them in real life wearing these berets and looking quite silly. It was nice to show them in normal life but still with an element of comedy about it."

There was also the conundrum of using colour in creating the world of the two actors who so many only know in black and white. Speranza says "Well the big thing was just seeing them initially, just seeing them not in black and white. And introducing colour into two very iconic people, comedians that you've mostly seen in black and white - trying to get the audience used to seeing them in colour. I spoke to JP [designer JP Kelly] at the beginning, he showed me all the sets and then we worked together with Jon. There's just so much information about Stan and Ollie, there are tons and tons of reference, which really helps. And then with the locations trying and trying to get their American feel about them, trying to make them stick out in an English environment. So it's a work in progress. I like to do lots of mood boards of colours, then for example we tried to keep colour for this scene in Worthing very Technicolour, and then more green in Ireland, just trying to make certain areas more specific."

Speranza's personal most memorable moment is the Way Out West dance. "When they did the dance, the Way Out West dance on stage, because I've watched it on film so many times. Stop, pause, stop, pause, stop, pause all the time, trying to see all the little details of what they wore I actually burst into tears when I saw them do it, I got very emotional. It was just lovely to see them doing that dance, I've seen it so many times, seen the actual Stan and Ollie doing it, and the way they recreated it was just brilliant, that was one of my favourite moments."

Designing Stan & Ollie

The story of Stan & Ollie not only covers two distinct time periods but also two completely different worlds: the glamour of 30s Hollywood and the somewhat dreary gloom of 50s Britain. It was an exciting challenge for BAFTA award-winning production designer JP Kelly to bring these contrasting landscapes visually to life.

"There's a colour palette from the grandeur of 30s Hollywood to the dark dankness of a rainy day in Newcastle to London in all its post war recovery splendour. Then there is the simplicity of arriving in Ireland, which is like a group hug for the film at the end. Each of those have to have a different quality that was really the design brief for how we balanced all those different looks together and how we showed progression in their journey, and to contrast it of course with the 1930s and this Hollywood lifestyle which they had which was sunny and shiny and exactly the opposite to a rainy day in Scunthorpe."

To realise the exteriors of Hal Roach studios in its heyday, the production knew there was only one location in the UK that fit the bill: Pinewood Studios. The team researched the films being made at the Roach Studios during that period - children's franchise The Little Rascals - and augmented this with roman centurions and Egyptian pharaohs, phasing in cowboys and saloon girls as Laurel and Hardy approach the Way Out West stage.

A busy bustling studio, supervising location manager Camilla Stephenson knew finding a window at Pinewood to mount the complex scene would be challenging. "We had to come on Sunday because we would literally have Stormtroopers walking past," she laughs. "We still had to change a lot of things to make Pinewood work. A lot of productions helped us out by hiding their equipment. We asked Jurassic World if they would move a container and they said, 'It's not a container, it's a raptor cage!'"

Kelly elaborates on the challenges of the scene "We really wanted to create a world that showed Laurel and Hardy's success but also the excitement and contrast with the world we end up in for most of the film, which is in England. Pinewood Studios has very little to do with Hollywood but was built around the same time, so architecturally a lot of the buildings are able to just about pass as Hollywood studios. We then made set extensions at the end of streets so you can see Hollywood hills in the background and so on. And then the characters arrive at the Way Out West stage, which was in Twickenham, where we're meticulously recreating the scene from Way Out West, which is where they arrive at the saloon and they do their famous dance. This was a really fun set to create. There are really two aspects to it: a saloon bar where we'll have the Avalon brothers sitting outside singing and then amazingly at the time, which most people won't have realised when they watch the film, that the Way Out West scene of them dancing was shot with a back projection. And if you look at it, very carefully you can see a definite line between where they're standing and projection behind them."

The exciting thing about that backdrop was that the team managed to track down the very one that was used in the original shoot! Researcher James Hunt tracked down the original archive that held Laurel and Hardy material and was put in touch with Jeff Goodman who works at the Producer's Library. Jeff was incredibly helpful and it turned out that he had been the archivist who had put the material into store way back in the day! He knew exactly what we were looking for sent two pieces of the original backdrop to ensure the piece could work.

For the studio interiors, a staffroom at the grandiose Eltham Palace in Greenwich doubled for Stan and Ollie's dressing room while the Way Out West set was painstakingly recreated at Twickenham Studios right down to the mule. "It was tough because we wanted to get it pinpoint accurate," explains Baird. "If you step back far enough and play them both together, you would struggle to see which one was which - that's how we wanted it to be." Also at Twickenham, the team created a set for a fantasy sequence depicting Stan & Ollie's never made Robin Hood comedy Rob 'Em Good.

"We purposefully recreated a strange looking Sherwood Forest in keeping with the Laurel and Hardy one," laughs Kelly. "It had a river running through it and a huge amount of greenery, all completely inappropriate for a forest in the Midlands. As soon as you put actors in Robin Hood costumes in the middle of it, it looks like you are in the middle of a Technicolor epic. It was funny. We built loads of lovely and elaborate sets but everyone raved about that set the most. It really got people's Laurel and Hardy juices flowing."

When the action switches to Britain, Stan & Ollie becomes a road movie with the legends travelling the length and breadth of Britain. Similarly, Kelly and Stephenson combed the country looking for theatres that were both period-accurate and fit the needs of the story. Theatres used included The Old Rep in Birmingham, The Fortune Theatre in London, building to The Hackney Empire, which doubled for the Lyceum, the venue for Laurel and Hardy's triumphant London show. As the pair moved around the country, they discovered a similar pattern.

"We'd go to a theatre and they'd say, 'Laurel and Hardy performed here, we've even got a poster'" says Stephenson. "They were absolutely across all these rep theatres."

The Britain that Laurel & Hardy tour is a landscape of run-down boarding houses, and cheap-and-cheerful lidos. Kelly wanted to accentuate the contrast of two Hollywood legends amidst the post-war austerity, especially in the North of England. But the team were wary of straying too far into traditional British film territory.

"There is a certain expectation with British film for it to be grimy, for the pace to be a bit slower and for it to be real," says Baird. "It had to be true to the 50s but it had to match up tonally to the whole film. We've not overly designed anything. Things are rubbed down a little bit but it doesn't come out like social realism. We wanted it to make it feel like Britain but also not to depart too much from the tone of the film."

When the action reaches London, much of the drama unfolds in the Savoy Hotel. The production utilised the hotel exteriors but recreated the foyer and restaurant at the Park Lane and the rooms at West London Studios. Although not completely historically accurate, Kelly carried the Art Deco stylings of the Park Lane into the interior rooms to add a touch of opulence that demonstrated Laurel and Hardy were on the up.

"What was grand in the fifties isn't so grand by today's standards," says Kelly. "In reality the Savoy's rooms were modest compared to today. There is a balance between historical accuracy and contemporary audience expectations of what a big hotel looks and feels like. At the end of the day, we are storytellers so that has to be the key consideration."

Faye Ward recalls "One of the most memorable days was when we recreated Cobh Harbor in Ireland. We couldn't actually go to Cobh Harbor, so we cheated it in Bristol Harbor, which was fantastic. It was a sunny day and we had this incredible vintage ship there and had about 350 extras, all dressed in Irish textures along with authentic reproduced banners and we recreated that wonderful arrival. The Irish church at Cobh Harbor played The Cuckoo Waltz, through the bells, for their arrival, which was really wonderful. And it was their journey from England to Ireland at the last moment of their tour. It was such a special day and JP and Guy did an exemplary job, it was a very special day and I am sure that will come across in the film."

This moment of Laurel and Hardy receiving the warmest welcome in Ireland also resonated with Kelly. "My uncle had seen them in Dublin in the 1950s," says the Ireland-born designer. "I've always known that story. He's in his 90s. He's delighted about that."

'Delight' is a notion that comes up a lot discussing Stan & Ollie. For Jeff Pope, it is the heart of Way Out West, the simple scene of two men dancing just for the joy of it, that inspired the project.

"You just sit there and laugh about how much they love being together and how they can take enjoyment in such simple things. I think that is why they are still so loved. We can look at them and think: 'You know what? It doesn't take a lot to get happy.' We complicate it too much now. If you look back at them, they can get happy so easily."

It is this bright innocence that resonates with Faye Ward. For her, it is one of the reasons Stan & Ollie, a film about legends from the golden age of Hollywood, is a film for right now.

"We are in a place and time where people are pretty scared of life," she says. "Watching their routines is just so heartwarming. There is a pure joy, an innocence to what they bring which I think is really great and fun for audiences today. Half the audience are crying and then laughing just because it is incredibly clever but simple at the same time. It's so lovely and actually I think we really need a bit of that at the minute."