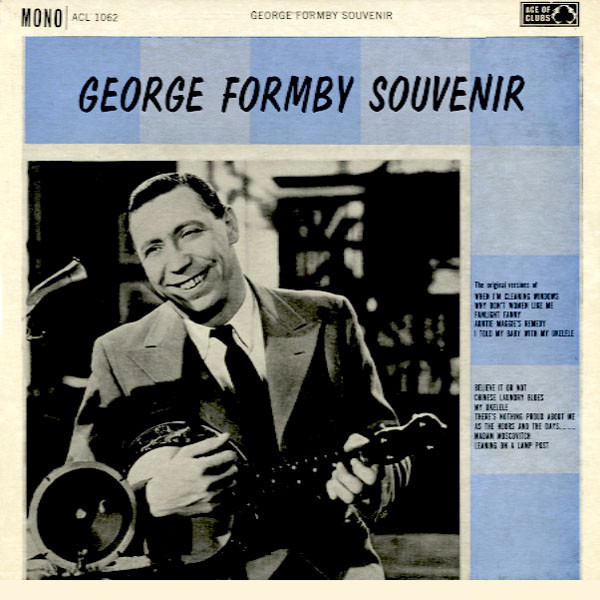

George Formby - George Formby Souvenir (1961)

1961 - George Formby

George Formby Souvenir

Ace Of Clubs ACL1062

Released early in 1961, the sleeve notes for George Formby's first long playing vinyl collection, George Formby Souvenir, positively beam with a sense of optimism and anticipation:

"At the time of writing, George Formby is resting at home in familiar West Lancashire surroundings; confidently he talks of his Summertime plans; bravely he looks forward to busy times."

The 1960s had indeed begun well for Formby, and his cause for hope and busy times ahead was genuine. Following a long break from performing after a string of health problems, 1960 had seen the star gradually returning to live shows again, and the signs were there that his career would go from strength to strength over the new decade. Even though his wartime glory days were by now well in the past, the British public still had a great deal of affection for George and his cheeky tunes.

After a nine year absence from the recording studio, Formby had been tempted back by Pye with the promise of recording new material for a potential album. The two tracks recorded by him in May of 1960, Happy Go Lucky Me and Banjo Boy, saw him enter the UK pop charts for the first time since they were first compiled in 1952.

A record-breaking summer season at the Queen's Theatre, Blackpool, with the show The Time Of Your Life had been another great success, with the BBC recording one of the shows for broadcast on TV. This was followed by an appearance in the December of 1960 on the BBC's Friday Show, which saw Formby reminiscing about his long career in between performing some of his old favourites, appearing on stage, solo, for 35 minutes straight. To finish the year, he would continue his career resurgence with a run in panto as Mr Wu in Aladdin at Bristol Hippodrome.

His professional life aside, there was also another reason for Formby's sudden optimism in 1961: George's formidable wife Beryl, who had done so much to guide his career during his earlier glory years, had passed away on Christmas Day 1960 in the middle of her husband's run in the pantomime. She was cremated just two days later in a short service that saw few attendees, after which George immediately returned to Bristol.

Beryl had been an uncompromising and intimidating presence for all of George Formby's career, arguing with theatre managers, film producers and even prime ministers on his behalf, destroying as many career opportunities as she helped create. While initially, that intransience and stubbornness had helped Formby to progress, by the time of her death the relationship between the couple had long turned sour and bitter, George's many affairs and faltering career a testimony to the breakdown of the marriage.

Far from her death ushering a time of mourning and sorrow, it was at last a chance for George to break free from the confines of Beryl's domineering and aggressive form of management, and to start to enjoy his life again, both personally and professionally. To the surprise of many, on Valentine's Day 1961, he announced his engagement to Pat Howson, a young schoolteacher twenty years his junior, with the marriage scheduled for May.

Sadly though, nothing was to come of his new-found hopefulness and expectation: on 6th March 1961, the national treasure died of a heart attack, aged just fifty-six. In contrast to his wife's quiet and sparsely attended funeral, George Formby's burial saw thousands of mourners line the 20 mile route from St Charles Roman Catholic Church in Liverpool to Warrington Cemetery where Britain's once most-popular film star was laid to rest next to his father, the former music hall star and early inspiration for his career, George Formby Snr.

By the time George Hoy Booth (AKA George Formby Jnr) was born in Wigan on 26th May 1904, his father (below) was a well-paid and popular entertainer, known to variety audiences all around the country for his musical comedy act - and his act was reputedly the inspiration for Charlie Chaplin's Tramp.

Formby Snr had known many years of poverty, struggle and hardship, and wanted better than a lifetime spent touring the country's music halls for his son. Small, nervous, and underweight as a child, it was decided that George Jnr would make an ideal jockey, and at the age of just seven his father pulled him out of school to learn a trade as a stable boy. It was a hard life for the young George, filled with early starts, physical exertion, bullying, and long periods of isolation from his family. In 1914, at the outbreak of World War One many trainers chose to send their horses to the relative safety of Ireland, accompanied by their stable staff. Young George Formby made the journey too, to the village of Athgarvan near The Curragh Racecourse, an experience that would further compound his isolation and despair.

Formby was aged just ten years old and the loneliness soon became unbearable. Frequent attempts to escape the stables in Ireland and return home were all thwarted, but by the end of the war (and despite all his best efforts) George Jnr had somehow managed to become a fully-qualified jockey, albeit never a very successful one. It was his father's tragic death of tuberculosis aged just 45 on 8th February 1921 that was to prove a turning point. George Jnr travelled from Ireland to Warrington for the funeral, and with a few days to spend in the company of his family before returning to Ireland, George's mother Eliza decided to take her son on a trip to London and the Victoria Palace Theatre in an effort to raise his flagging spirits.

It was there that they witnessed the comedian Tommy Dixon, presenting himself on the bill as 'The New George Formby', stealing all of Formby Snr's act: jokes, routines, material - costume and all. After their initial anger subsided, George Jnr and his mother were both determined that if anyone were to be the new George Formby, then it would be him. And so, just ten weeks later in April 1921 at The Hippodrome Cinema in Earlestown near Warrington, the possibility of a career as a jockey gladly forgotten, George Formby Jnr took to the stage for the very first time.

Initially Formby Jnr's act was a direct copy of his father's, with the well-known and established routines guaranteeing a ready and appreciative audience wherever he appeared around the country. The cheeky, happy-go-lucky, ukulele-plucking character he became famous for would take some years to develop. Key in that transformation, for better and often for worse, was his aforementioned wife, then a young clog-dancer from Accrington named Beryl Ingham. The two met while performing on the same bill in Castleford, 1923, and were married within the year (pictured together, below). Beryl was to remain a possessive and controlling presence for the rest of George's life and career, guiding him onwards and upward to stardom, no matter what obstacles or circumstances were placed in her way.

George Formby first ventured into a recording studio along with his mother in February 1924, when they visited the HMV studios at Hayes to record a song written by his father. No commercial release came from that first early session, and with no offer of any further sessions forthcoming, Formby returned to the halls. By the spring of 1926 though, the ever-insistent Beryl was acting on George's behalf, and had negotiated a one-off deal with Edison Bell Winner to produce some new recordings of songs made popular by Formby Snr, and all sung very much in imitation of George's father. The discs were released in the autumn of that year and made very little impact, being more sought after by devotees of Formby Snr than any of the younger man's fans. Far from being the start of a new career, Beryl's tight control of George's professional life and her exorbitant demands meant that it would be some years before George would be being invited back into a recording studio.

However, Beryl had encouraged George to start developing an act of his own, free from his father's influence. While in theatrical digs in Barnsley, he had learnt how to play the musical instrument that will forever be associated with him: the ukulele (and often, actually, a banjolele). His first instrument, bought for 15 shillings from a Manchester second-hand shop was a wise and shrewd investment. The instrument was gradually introduced into his act, and by the time he signed a three year recording deal with Decca in June 1932, George Formby was at last ready to begin taking Britain by storm.

George's first two recordings for Decca, Our House Is Haunted and I Told My Baby With The Ukulele, were both rejected, but by July he had recorded two songs which that finally see a release. A-side Do De O Do is a fairly pedestrian, plodding song, with a pleasing Nat Gonella trumpet solo its most enjoyable element. The B-side, however, Chinese Laundry Blues, written by Jack Cotterill, was just what George needed.

This much more lively song relied more heavily on George's uke skills than on the assembled orchestra, and introduced the world to the wonderfully realised character of industrious Chinatown resident Mr Wu. While in 1932 he seemed more than happy with his career in a Limehouse Chinese laundry, over the next ten years Mr Wu would enjoy all sorts of adventures and alternative careers - all but one recorded by Formby and gratefully received by his fans. Indeed, the record proved immediately popular enough with the public to see Formby return to the Decca studios again in the October of 1932. His career had at last taken off, and when not filming or touring, George Formby continued to record a string of popular hits until 1946.

Chinese Laundry Blues was still popular enough nearly thirty years later for it to open side two of George Formby Souvenir. More popular than even that track though, was the side one opener When I'm Cleaning Windows. Packed with Formby's celebrated sauciness, the song is a rich sequence of knowing winks and nods to the audience, as his imagined window cleaner spies on ladies in various states of undress and casts admiring glances at the antics of honeymooning couples from the top of his ladder. Initially recorded in September 1936 (although the version on the album dates from 1950), When I'm Cleaning Windows - AKA The Window Cleaner - first appeared in George's film of the same year, Keep Your Seats Please.

An early and now lost silent aside, his movie career had begun in 1934 with Boots! Boots!, represented on George Formby Souvenir by the comical yet still plaintive Why Don't Women Like Me. From that moment on musical numbers and routines played an important role in all of George's films. Whatever triumphs and failures George went through onscreen were mirrored with songs sung to the accompaniment of a hastily produced ukulele. His recording developed very much in tandem with his film career, and each new movie would see a subsequent set of releases for his fans to enjoy.

When I'm Cleaning Windows was written by the prolific team of South Londoner Harry Gifford and Liverpudlian Fred Cliffe, with Formby also receiving a lucrative credit on Beryl's insistence, despite having very limited input to the actual creation of the song. Gifford and Cliffe account for seven of the twelve tracks on George Formby Souvenir and their influence is clear, with songs that perfectly capture the essence of George's persona, with innuendos and double entendre abounding. Other songs on the album in a similar vein include three Jack Cotterill (sometimes spelled Cottrell) tracks, and one written by Eddie Latta, who again captures Formby's skills at delivering saucy material with Auntie Maggie's Remedy. On a sombre note, when not writing songs, regular collaborator Eddie Latta was also an undertaker in Liverpool, and would eventually conduct Formby's funeral. Such is the circle of life!

The last track on the album stands out as something different. Leaning On A Lamp Post is like few other George Formby tracks. It is by turns touching, melancholic and loving, strung through with genuine yearning and affection. There are no cheap laughs, no gimmicks or innuendos, and no jokes are told. First performed in the 1937 film Feather Your Nest (clip below), the unlikely plot revolves around sound technician George having to secretly re-record the ballad after destroying a master disc of it created by another artist. Formby of course wins the hand of the young female lead, and achieves great fame and fortune, just as one would expect.

Written by Noel Gay, the song was an enduring one and featured prominently in Stephen Fry's 1985 revival of Gay's musical Me And My Girl. Sadly, thanks to Beryl's insistence that George share writing credits on any future collaboration with Noel Gay, it was to be the only work he wrote for Formby but clearly demonstrated that there was more to the much-loved entertainer than just the cheeky, giggling comedian strumming his uke. There was also a confident, assured and competent self-taught musician and performer.

After his wartime heyday, George Formby spent little time in the recording studio. His efforts in the 1950s amounted to little more than re-recording some his earlier hits, most of which appear on George Formby Souvenir. His two 1960 recordings are not typical of his work, maybe hinting at a new direction, and are not hugely popular amongst Formby fans. But who can blame him for attempting something different and novel after so long in the public eye?

It is anyone's guess where a fit and healthy George Formby might have gone, and what new heights he might have reached if he had made the most of all that optimism and enthusiasm he had in the early months of 1961. His recording work has been collected and compiled on numerous reissues ever since his death and shows no signs of being forgotten any time soon, and a new series of high definition remasters of his box office-topping films have in recent years renewed his accessibility. George Formby remains a remarkable and uniquely British talent.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more