Starship Titanic and Douglas Adams' other adventures in video games

The intriguing and altogether bizarre story of The Starship Titanic began life not as many people may have believed as a book written by Douglas Adams, or even a book written by Terry Jones, but as a computer game.

Appropriately, the latest Radio 4 special (broadcast Sunday 19th December) set in the Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy expanded universe stars Michael Palin as the Encyclopaedia Galactica, and Simon Jones (Arthur Dent himself) has a cameo. But the question on many people's lips may be how did this interesting collaboration between two best friends, Douglas Adams and Terry Jones, come about in the first place? To find the answer you have to go back to the start, namely the start of Douglas Adams's fascination with technology and particularly video games.

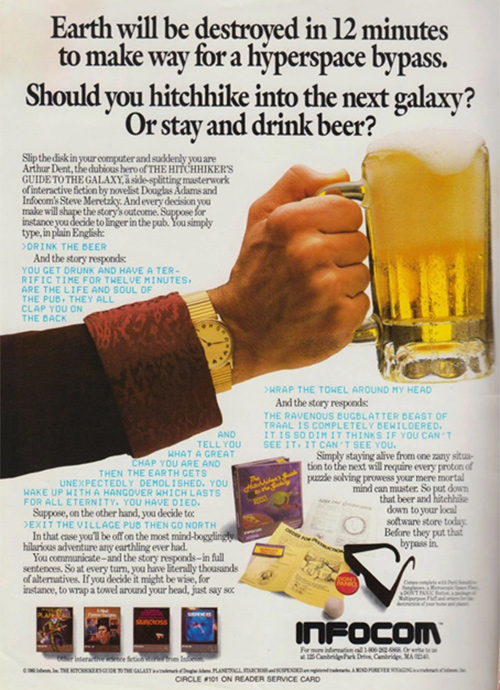

It was March 1985 when Douglas Adams arrived on the set of Micro Live (a TV programme developed in conjunction with the BBC's Computer Literacy Project) to tell Fred Harris about his latest innovation - a computer game version of The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy.

It was still early days for the video game industry. Super Mario Bros had only just been released, and prior to this injection of quality into the video game market by Nintendo, any games that tied in with films or a TV series were looked upon grimly, thanks to the infamous ET game scandal of 1982 (the game's reputation of being largely unplayable resulted in an estimated 700,000 unsold/returned copies being buried in a New Mexico desert - several thousand of the fly-tipped games were excavated in 2014, most still in their original boxes).

And aside from a series of adverts Morecambe & Wise starred in for Atari (the games console the notorious ET game was created for), there was very little in the video game world for comedy fans.

For a bestselling author, the decision to move into the world of video games would probably have appeared to have been a little odd back then. On the surface, many would have written this move off as a cheap cash in. They might have thought that Douglas Adams had simply signed the rights away for a standard Space Invaders style shooter to have a few H2G2 references crowbarred in. That would have been a fairly easy thing to achieve, and would surely have been popular; you can certainly imagine a shooter in which things turned into whales, or you got 42 points for taking out a bowl of petunias, but that was not what Douglas was out to do.

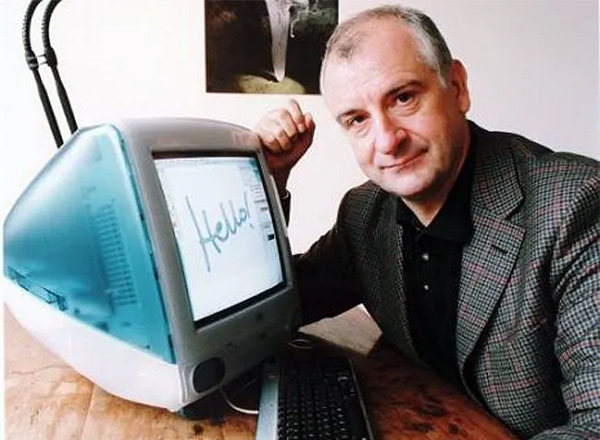

Adams was convinced that video games were the next big thing. He had an obsession with computers; he was the first person in the UK to own an Apple Macintosh computer (Stephen Fry was the second). He proudly typed Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency on his own Mac II - this early incarnation of modern word processing allowed for a much more precise edit, as he created arguably his most intricate masterpiece.

But, back in the early eighties when he should have been working on his fourth Hitchhiker book, he instead worked on the concept of turning The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy into a game... an adventure game.

"This is actually turning a book into a game," Douglas proudly announced on Micro Live. "You become one of the characters, in fact, in this particular game you become several of the characters, so you've got to be careful how you treat them, or you might find it coming back on you," he told Fred Harris with a grin.

It was a text adventure game, and while not the first of its kind, it was certainly the first to be written by a best-selling author. This was not just the first Hitchhiker's book reshaped into a text adventure either, this was Douglas re-visiting and re-writing his iconic book. As such, he packs even more detail into the story and, this time, that famous dressing gown is mentioned from the word go (it was absent from Douglas's work until the third book). You wake up as Arthur Dent and your first task is to turn the light on, pick up your famous gown and look at the contents of the pocket. Inside is:

"A thing your aunt gave you which you don't know what it is, a buffered analgesic, and pocket fluff."

If you type in 'Look at the thing' you will receive the response:

"Apart from the label on the bottom saying 'Made in Ibiza' it furnishes you with no clue as to its purpose, if indeed it has one. You are surprised to see it because you thought you'd thrown it away. Like most gifts from your aunt, you've been trying to get rid of it for years."

Grabbing Arthur's toothbrush will elicit the response:

"As you pick up the toothbrush a tree outside the window collapses. There is no causal relationship between these two events."

And this is how the game continues, with a sense of humour perhaps even more droll than that of any other versions of the Hitchhiker story.

"That's amazing," Fred says as Douglas shows off the gameplay, "it's almost like plain English."

While text adventure games were becoming popular in the eighties, and were already reasonably well established, there was indeed something a little more special about this game. It was clearly a labour of love for Douglas. Even the packaging was beautifully made. Along with the game, you received a copy of the planning council demolition orders, some fluff, a microscopic space fleet (which to the untrained eye is merely a small empty bag) and even a pair of Joo Janta 200 Super-Chromatic Peril Sensitive Sunglasses.

This extravagance paid off. Upon its release, The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy game was the best-selling video game in America, selling over 500,000 copies. What seemed a bizarre flight of fancy for a successful author had turned out to pay handsomely; however, Douglas was never in it for the money, he rebuffed any criticism that turning his best-selling book into a game had in any way cheapened his original work.

"You can't compare interactive literature with literature, if you do, you can very easily make a fool of yourself. When Leo Fender first invented an electric guitar, one could have said, 'but to what extent is this real music?' to which the answer is: 'Alright, we're not going to play Beethoven on it, but at least let's see what we can do'. What matters is whether it's interesting and exciting. The thing I like about this, is that I can sit down and know that I am the first person to be working in this specific field. When you are writing a novel, you are aware that you are manipulating your readers, here you know you are going to have to make them think how you want them to reason, I don't regard it as being an abdication of creative art. In fact, there is a sense in which now the author is even more in control, because the reader has more problems to solve. All the devices of a novel are still at your disposal, because a novel is simply a string of words, and words can mean whatever you want them to. It just offers the opportunity to have a lot of fun."

It may have even seemed like a contradiction for the Hitchhikers franchise to have boldly stepped into a new field of technology. The books are on the surface massively sceptical of modern tech. Sirius Cybernetics is one giant dig at ill thought-out corporate innovations, and of course we have that famous running gag about humans being so amazingly primitive that they still think digital watches are a pretty neat idea (it is indeed a metaphor that could extend to the smart watches of today). Yet, Douglas was essentially satirising himself with this joke.

Douglas's next game is probably his most obscure work, although not all of it was his own. Adams was famously the writer that didn't enjoy writing; he never finished anything to a deadline, something he was quite happy to laugh off, "I love Deadlines, I love the whooshing sound they make as they fly by," he once famously joked.

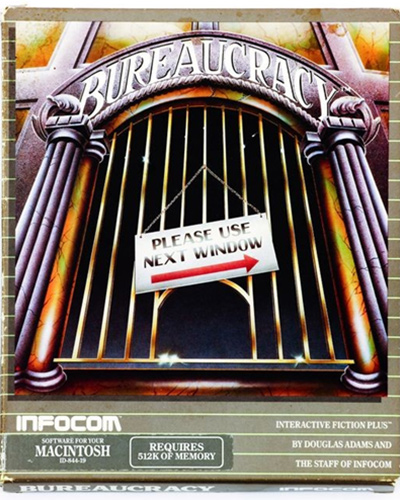

In the case of his second game, Bureaucracy, a deadline had indeed gone whooshing by, and as a consequence the second half of the game is written by another hand. Notwithstanding, most of it is quite plainly Douglas's work.

The game was inspired by Adams's frustration at being unable to notify his bank of a change of address. His fundamental irritation with this sort of thing was epitomised by the Vogons. It seemed to Douglas that villains who were not really villains at all, merely inflexible, menial, clerical workers, who loved nothing more than the pointless enforcement of laws and regulations with no care for their consequences were the worst of humanity, or indeed Vogonity.

To an extent, this point was driven home further in the 2005 Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy film, in which Martin Freeman's Arthur trapses from window to window trying to get Trillion freed with paperwork. Scenes which bare strong resemblance to Bureaucracy's gameplay, as the text adventure teases the player by asking them to move from one window to the next to the next, and to the next. At one point the player finds themselves at a restaurant giving a complex order, you are asked "what drink you would like?" "Would you like fries?". After answering a myriad of questions you are informed that their computer has malfunctioned and can you please do it all again? In the top left-hand corner is your blood pressure and your goal is to keep it down, it will go up when you encounter these sorts of situations. If it gets too high, you'll have an aneurysm and it's game over.

Bureaucracy is a unique experience, and is probably the only paperwork-based game that also features a hungry llama.

The gameplay was very much in the style of the Hitchhiker's game. And it too was bundled with accessories. But without the Hitchhiker name attached to the game, it struggled to get noticed.

Douglas would leave the video game world for a time after this. However, his obsession with technology would only increase. In 1995, he produced a fantasy documentary for the BBC, Hyperland. Although Adams was a comedy performer in his youth at Cambridge Footlights, this is the only record we have of Douglas acting outside of his audiobooks. In the film, Douglas Adams has decided that he hates his television, he's completely done with it.

"I had a dream last night, as a result of a hard night's dozing in front of the television," he tells us via voiceover, whilst we watch him dreaming.

"I dreamt that I'd finally decided to get rid of the thing. I thought there must be a better way of spending my time. It seemed such a waste of the technology, maybe in the future we'll find a better use to put it too..."

So, he picks it up, holds it at arm's length and takes it to a landfill site. There he meets a rather dapper Tom Baker, who like magic, emerges from the television screens piled high amongst the rubbish.

"Are you tired Mr Adams, of the sort of television that just happens at you? That you just sit in front of like a couch potato?"

"Who the hell are you?" Douglas asks.

"Me?" says Tom Baker, "oh, I'm just him. My name is Tom, and I'm your agent. May I ask if you know what that means?"

"You want fifteen percent?"

"It means that I'm here to do your every slightest bidding, to fetch and carry for you, to work tirelessly and selflessly on your behalf, always ready, always willing, no job too small or too menial."

"Are you sure you mean agent?"

"I mean that I am a software agent. I am merely a simulacrum, an artificial and completely customisable personality, and I only exist as what we call an application in your computer. I have the honour to provide instant access to every piece of information stored digitally anywhere in the world. Any picture or film, any sound, any book, any statistic, any fact, any connection between anything you care to think of ... you've only to tell me, and it will be my humble duty to find it for you, and to present it to you for your interactive pleasure. Is there anything I can do for you now, Mr Adams, Sir?"

"Well yes," he replies. "You can stop being so obsequious for a start."

The film is part humorous fantasy, part in-depth documentary; it offers a glimpse into the future from the perspective of technology in 1995. Here Douglas essentially predicts everything we have now: computers in every home, AI assistants, touch screen interfaces. A year after the film, a real obsequious search engine in the form of a butler would arrive in the shape of Ask Jeeves (1996), while arguably the king of search engines, Google, arrived in 1998. Douglas would also set about trying to sort the internet out into some sort of editable online encyclopaedia in the style of his fictional guide in the late 90s... Wikipedia launched a little later in January 2001.

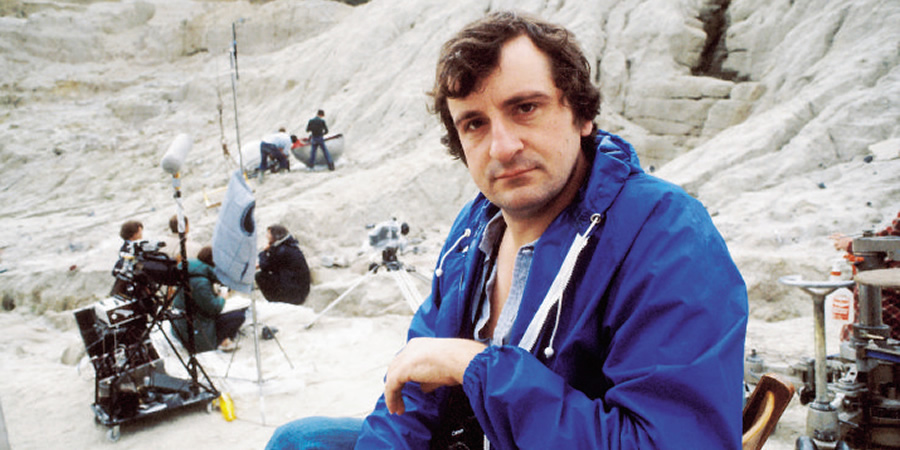

A few years after his adventures in Hyperland, Douglas embarked on his most ambitious project yet, an adventure video game that used 3D graphics and voice acting. it was the last project he saw to its completion in his lifetime, Starship Titanic.

The video game market had changed beyond all recognition since Douglas's success with the Hitchhiker text adventure game, therefore much more was now expected. For his first foray into the new world of computer games with graphics, Douglas was inspired by one of the first PC games to develop popularity independent of console games, Myst.

Although most people today are unlikely to remember it, Myst was a very big deal in the nineties. The game dumped players in an atmospheric spooky location and left them to work out what on earth was going on. The game featured locked room mysteries with fiendishly difficult puzzles, essentially, it was a text adventure game with graphics, and they were good graphics for the time. The game provided a tense atmosphere, but was largely plotless. Douglas Adams called Starship Titanic "Myst, with things happening,' and that became the remit for the entire game.

Booting up Starship Titanic is at first a bewildering experience. It presents a very H2G2 start: it's a normal day in your living room, select the TV and Douglas Adams will appear and tell you, "For heaven's sake, don't just sit there get on with it." Then suddenly a giant spaceship crashes into your front room. You're greeted by a bellbot, who asks you a series of questions, after which you're left to your own devices.

Blindly clicking around, you will find some very depressed monkeys in gasmasks, you can also pick up a seriously annoyed parrot voiced by Terry Jones, and in that action, you'll receive a feather. You'll eventually find yourself interacting with a bomb (voiced by John Cleese) who casually starts counting down to detonation. All whilst on board announcements randomly inform you that 'All art classes are cancelled'. If you go back to the lift at this point, the liftbot will start to ask you about the bomb you've left ticking away. So, you end up coming to the conclusion that the best course of action would be to start again with a walkthrough, lest you blow the whole game up.

Starting with a walkthrough is indeed the best advice to give anybody who is about to start playing a Douglas Adams game. "User mendacious" was how Douglas described his games. But with every mistake you make, there are carefully crafted jokes that play out before your game is over. It's unlikely that even the most ardent Adams fans would have found them all.

There's a lot of fun to be had in Starship Titanic, particularly in chatting with the liftbot. Asking after any Douglas Adams characters will elicit the response 'Very droll sir, but ultimately unimpressive.' You can type absolutely anything to see if you're able to get an interesting response - for example, you can ask 'Do you know Arthur Dent?' to which he curtly replies, 'Nobody likes a smartass, Sir.'

Despite winning an award, the game didn't receive the same level of acclaim that The Hitchhiker's Game had back in the eighties, largely because things had moved on so quickly. The arrival of 3D graphics had pushed out the Dungeons & Dragons style text adventure games. Cryptic mystery games were out of fashion, Myst's heyday had come and gone, as adventure action games were becoming a major draw for PC gamers.

The experience Douglas strived to bring to the world of video games is perhaps more popular now than it was then. It is almost certain that a game such as Portal has a lot to thank Starship Titanic for. Portal was a wildly successful sarcastic puzzle game, ruled by the sinister and comically dry, GLaDOS, who is the seriously twisted computer operating system that chips in surreal gags, whilst the player focuses on their task. The developers of the game cited British comedy as a key influence to their writing of the game, so much so, that in the sequel Stephen Merchant voiced one of the main characters.

Papers, Please is another example of a darkly comic game that bears resemblance to Douglas's Bureaucracy, as players take up the role of an immigration officer with reams of paperwork to sort through; while in the early 2000s games such as Phoenix Wright and Professor Layton, brought visual novel puzzle games to mainstream audiences for perhaps the first time.

Just as Douglas had proposed back in the eighties, the storyline for most video games has now become just as important as the gameplay. Yet even when Starship Titanic was launched, there were doubts that the game could carry the story by itself. Douglas was tasked with writing an accompanying book, however, he focused on the game instead. It was another deadline that whooshed by, another thing that he just hadn't got around to. Terry Jones explained the situation:

"He'd been paid an advance seven years before to write the book, and he never had - so he fobbed them off with a computer game. He rang me up and asked if I would like to write the book to get him out of a hole. I asked, 'how long have I got?' and he answered: 'Five weeks!'. So, there I was bashing away at a typewriter like when you see writers in Hollywood films."

True to his friend, Terry Jones did indeed dig Douglas out of that hole, he hastily wrote Starship Titanic, based on a rough outline given by Douglas in mere weeks. Despite the book being an extremely rushed job, in the audiobook Terry Jones sells his vision with a performance as impassioned as his parrot voice acting, making the whole thing a bit of a hidden gem for Phyton fans.

"It was the role he was born to play," Douglas announced on a chat show, while promoting the game. Before launching into a very impressive Terry Jones impersonation "He's not the messiah, he's a very naughty boy," he imitated. He also paid tribute to Terry Jones for going above and beyond for him, he once said that Jones had written "An altogether sillier, naughtier and more wonderful novel than I would have done." Yet the question hangs... why didn't Douglas Adams, arguably one of the greatest authors of modern times, want to write a book? Why had he lost his confidence?

Douglas liked to laugh off his problems with deadlines, but there lay a far more tragic side to his tardiness. Writing became a challenge for him, but, with the exception of this final Starship Titanic novelisation, it also became something that he was forced to do. At the zenith of Hitchhikers success, while he had been busy adapting his story into the television series and a stage show, Douglas had neglected his second novel altogether. After his publishers worked out that he hadn't even started work on the book by the final extension of the final deadline had come around, Douglas was moved into a flat to work on it. He later recalled:

"I was locked away so nobody could possibly reach me or find me, I led a completely monastic existence for that month and at the end of four weeks it was done. It was extraordinary. One of those times you really go mad. I can remember the moment I thought... I can do it! I'll actually get it finished in time, and the Paul Simon album had just come out, One Trick Pony, and it was the only album I had. I'd listen to it on my Walkman every second I wasn't at the typewriter. It contributed to the sense of insanity and hypnotism that allowed me to write a book in that time."

This wasn't the only time Douglas would find himself locked away at the hands of his publishers. The most famous incident occurred during the making of Douglas's fourth Hitchhiker book, So Long and Thanks for All the Fish. This was the book he had neglected in order to create that first, massively successful Hitchhiker video game.

The events surrounding the book's publication became so notorious that they were even turned into a play, We Apologise For The inconvenience - although this play offered an entirely fictionalised account, as Douglas sits in the bath having a conversation with a rubber duck (Douglas was famous for his love of almost day-long baths, and of course, one is never alone with a rubber duck).

Sonny Mehta, was the editorial director of Pan Books at the time, who later relayed the unbelievable story for Nick Webb's, Wish You Were Here, one of the first Douglas Adams biographies. Previously most people had wrongly assumed that Douglas's own brief retelling of the event had been overexaggerated, however, that was not the case:

"I did lock him up in the hotel room, that is true," Mehta said. "I came up with the wheeze of putting him in a hotel room some place. But there was no good putting him in a hotel room, if he wasn't going to be supervised. So, I said, 'Look, I'm going to do this: I'm going to get a hotel room and I'll move in myself and make Douglas churn out pages.'' Everyone thought it was a good idea, if I was prepared to do it.

"I explained the routine. I'd get him out of bed; he'd go up for a swim; we'd have breakfast, finish by 8.30 am and Douglas would sit down at this small desk with a typewriter, and I would sit in an armchair at 45 degrees from that, my back facing him, and I'd read a manuscript. I'd wait for the sound of those fingers on his typewriter keys, which sometimes would kind of happen, sporadically, and then there'd be long periods of silence, and I'd turn around to check him out and see that he hadn't croaked on me, or something. He'd be sitting up, staring out the window at this roof terrace. And every now and then I'd say, 'How's it going?' and he'd say, 'Fine, fine.' And you'd hear paper being crumpled and thrown into a dustbin.

"It was quite macabre, looking back on it. And at the end of the day, I would gather together whatever pages Douglas had written, and we'd talk about it. Then I would phone the office. In the evening we would go out to some restaurant round the corner, have a dinner, and then I'd bring Douglas back, and say, 'Okay Douglas, you'd better get some sleep', and he would be sent to his room. That is roughly what the routine was. And every now and then he would get up and play the guitar. And we'd talk a little bit, you know. And that was it. And every now and then I'd go through the dustbin discreetly, when he was gone to have a piss or something, to see what he'd chucked away, and it would say things like, 'Who the fuck does he think he is?'"

In hindsight, it was little wonder Douglas had become so disillusioned with novel writing. Another repeat of this situation for his final book was widely considered to be the reason that the last Hitchhiker outing, Mostly Harmless had ended so nihilistically and terminally with the deaths of almost every character.

Douglas's lifelong friend, fellow comedy writer and former flatmate Jon Canter, reflected on his struggles after the initial success of the first Hitchhiker book:

"I'd say, at that point he was probably the happiest that I ever knew him, because he'd written the first book, it was a huge success, people loved it. He felt vindicated I think, that he'd done this, and it had worked. I think the depression really kicked in when he had to write his second book, and suddenly, it was as if, he'd brought this gift to the world, The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy, and now the world was making demands on him, he was obligated to the world in a way that he wasn't when he began, it's probably true of most artists.

"There's a sense of people waiting for you to do your work, which he didn't' have when he was unknown, and he found that pressure almost unbearable. And famously, although he wrote in his Highbury flat, in order to finish his second book, he had to be effectively imprisoned in a hotel room, with his editor next door, waiting for him to deliver those pages. I find it sad to look back on that, I think Douglas took so much joy in his writing, but there came a point where it became a punishment as well as a joy."

It seems clear that Douglas Adams found solace in technology, in many ways he predicted the future, and he pioneered the idea of video games as a serious art form at a time when people were looking at him like he had... well like he was Zaphod Beeblebrox.

When people think of Douglas Adams, they might think of his vivid imagination, and perhaps his love of nature and technology, but very few would realise quite how much he suffered for his art, and how he championed the still overlooked world of visual novel video games.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more