It seemed a good idea at the time #1: Woody Allen versus a boxing kangaroo

We all know that moment in I'm Alan Partridge when, after free-falling all the way down his long list of top TV ideas ('...Arm Wrestling with Chas and Dave...Inner City Sumo...Youth Hostelling with Chris Eubank...'), the out-of-favour presenter finally hits rock bottom: 'Er...Monkey Tennis?'

Something weirdly similar must have happened back in 1966, when, inside an office at the British commercial TV channel Rediffusion, a programme meeting reached its climax when, through plumes of blue-grey cigarette smoke, some bright spark volunteered the idea: '...Kangaroo Boxing?'.

Amazingly, the bosses at Rediffusion thought that this was an excellent idea, and the result was that a real live kangaroo was put in a ring opposite a real live Woody Allen, the smartest American stand-up comedian of the time, inside a British TV studio, and a 'fight' was duly filmed. The true story of how this curious incident actually happened is one that involves Parliament, evolving technology, commercial opportunism and a sadly simple lapse of taste.

The story begins in the mid-1960s with the long drawn-out plan to introduce colour television to Britain. Colour TV had been a 'thing' in America since 1954, but (due in part to the lingering effects of post-war austerity, as well as a lack of consensus over what kind of new line system to pursue) British screens, by the early 1960s, were still limited to black and white. This in itself was a source of growing frustration for the broadcasters, but the nature of the decision to move ahead, when it finally came, would crank up that frustration to a far higher level.

On 3rd March 1966, the then-Postmaster General, Labour's Tony Benn, announced in the House of Commons that the government intended to authorise the country's new third channel, BBC2 (launched in 1964), to start broadcasting in colour for at least one hour per evening 'from December next year' (it would actually start on 1 July 1967, but both BBC1 and ITV would have to wait until 1969 to follow suit).

This infuriated the commercial channels, who protested that no 'sane' person was going to invest in an expensive new colour-ready TV on the promise of just one to four hours of programming each week. They added that ITV would not only be able and willing to broadcast far more hours per day in colour than the BBC, but could also start doing so far more promptly (an average of twenty hours per week, ATV's Lew Grade was promising, by September).

Tony Benn, in a textbook demonstration of how to make a fractious reaction even more fractious, suggested that, if ITV really was at such an advanced stage in its preparations, it could go ahead and sell its colour programmes to the BBC. This got the ITV bosses positively apoplectic, barking back at Benn: 'This we would never do'.

Their practical response was to look abroad. If Britain didn't want their colour programmes, then they would go ahead and sell them to America. They would start designing shows primarily for the US market, film them in colour, and then sell them overseas and screen them in humble black and white back in Britain.

This is why it came about, in the mid-1960s, that the commercial companies started to look to make 'spectacular' programmes that would (a) be suitably colourful and (b) would also appeal primarily to an American audience. It led to a brief fixation (especially at ATV) with staging big, brash and busy variety shows, full of action and incidents, and featuring plenty of stars who were very familiar to US networks.

One of these ventures saw Rediffusion, the commercial TV franchise holder at the time for London and surrounding areas, hurriedly revive an old format of theirs called Hippodrome. Having previously been a cheap and cheerful showcase for various home-grown music and comedy acts, it was now regarded as suitable to being opened out to serve as a kind of variety/circus hybrid show, hosted by an American star and accommodating everything from current pop performers and stand-up comics to internationally admired specialist acts.

It proved an attractive enough project to win over the major US network CBS, which bought it sight unseen for $1m, and - in an unprecedented commitment - promised it a prearranged slot in its coast-to-coast summer schedules: every Tuesday from 8:30-9:30pm, starting on 5th July. No UK-to-US TV deal had been struck quite so quickly or lucratively or definitively, and the bosses of Rediffusion were understandably delighted.

They were given plenty of pointers from CBS in terms of planning - including the suggestion that a 'zany' comedy animal act, amongst other things, would probably go down very well with American audiences - and they were happy to take them all on board. After all, they reasoned, the deal was not only good in itself - it was also good in terms of cultivating other collaborative projects. What CBS wanted, therefore, CBS would get.

Basing the production at the company's studios in Wembley Park, preparations began at the start of March. This is when some tensions crept in, both externally and internally.

Externally, it was all about the football World Cup. A big and spectacular TV show, with wild animals as part of the production, might have been considered by some of the more cautious local officials to be a recipe for chaos at the best of times, but in studios at Wembley during the spring and early summer of 1966, shortly before several games for football's quadrennial global event were due to take place at the nearby stadium, it was the cause of considerable conflict.

London's police were less than impressed by the prospect of having to contend for weeks on end with hundreds of variety fans, along with a wide variety of performers and sundry wild animals, in the same exceptionally congested area that they were already bracing themselves to deal with an influx of many thousands of sports fans during July. A number of very delicate diplomatic discussions were therefore needed between TV, council and constabulary chiefs before the officials were persuaded to treat the Rediffusion occasions as a 'useful' training exercise before the summer's main event, and that any stray animals that the England manager Alf Ramsey might later encounter would be restricted to members of opposing teams.

The internal tensions, however, would prove harder to manage and minimise. They arose initially because, in spite of the noisy protestations from commercial companies about being ready to start filming shows in colour, they were actually facing some tough trial-and-error technical challenges as they raced against the clock to record the shows on time.

The main problem was not just that the show would have to be filmed simultaneously by two completely separate film crews and directors (one using four old EMI black-and-white cameras, the other using new Marconi BD848 colour cameras, with the latter set - as infuriated British TV critics later kept pointing out - being favoured with the best positions), but also that few technicians in British TV (for obvious reasons) were used to filming in colour, and especially when filming 'as live' variety-style formats. The lenses of the new colour cameras were highly sensitive, only reproducing tones they recognised from within a range of primary colours, so a light blue, for example, could easily end up looking like a dark blue on the screen.

Rediffusion ended up recruiting a specialist outside 'colour' crew from the facilities company Intertel to minimise the potential for errors, but it still felt to many as though they were taking a leap not just figuratively into the dark but also literally into the light, as the lighting represented another part of the same problem. The studio lighting had to be almost ten times as strong for colour as it was for black and white studio recordings, which meant that the heat during each filming session would often be exceptionally uncomfortable for the performers and audiences alike.

Then there was the problem of costume design. The reason why this was a greater challenge than usual was the fact that outfits which looked good in black-and-white sometimes looked terrible in colour, and vice-versa. Rediffusion quickly decided that colour would win out when there was any compromise to be made, which rattled some of the designers who were used to working exclusively for black-and-white pictures.

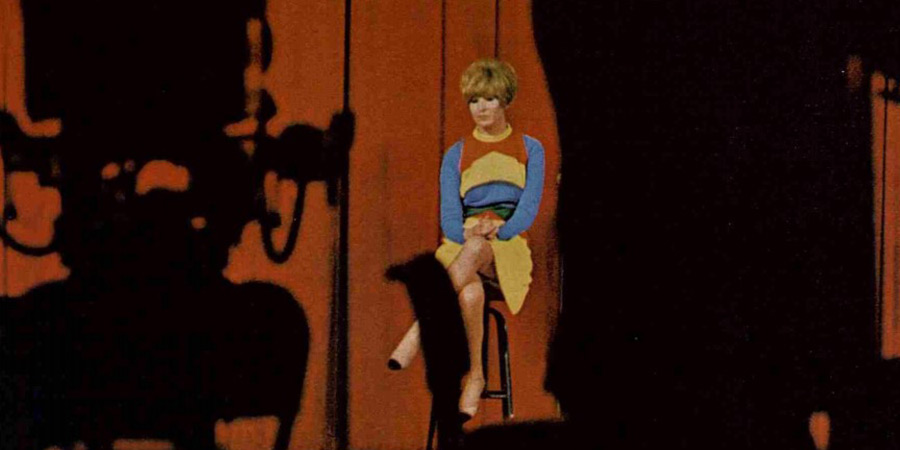

One innovation which was introduced to cope with the problem was that of the 'Colour Chart Girl' - a young woman in a multi-coloured dress who would be sent on to the stage about an hour before the recording was set to begin and sit patiently on a stool while the cameramen focussed on her and gradually got the range of colours clear and sharp. 'I have come to hate it,' the bored model chosen would soon complain. 'But they chose me because of my skin texture or something.'

While these technical tasks were being mastered, the actual programme was being put together. The first priority, to please the CBS bosses, was to assemble a set of major American stars to host each edition.

This, thanks to the contacts of the US investors, proved no real problem, with the likes of Merv Griffin, Nancy Sinatra, Johnny Mathis, Tony Randall and Trini Lopez all signing up quite quickly, either because they were already planning to be in Britain at that time or because they rather liked the idea of an all-expenses-paid flight over to London, with five star accommodation, for what promised to be a simple in-and-out autocue gig.

With the technical and personnel matters mainly settled, the production was thus able to proceed. The set - a giant circus ring - was constructed inside Rediffusion's huge 13,400 square foot Studio 5 (which at the time was the largest purpose-built TV studio in the whole of Europe, and whose floor, fortunately enough, had been tested specifically to withstand the weight of several elephants). Special entrances, exits, lifts and containment areas also had to be either built or remodelled to deal with all of the lions, tigers, elephants, bears and various other animals that were due to take part, while the large car park was taken over for the ten-week filming period by a veritable mini-village of trailers, caravans and cages.

Among the eclectic assortment of human performers set to be featured on the shows were 'daredevil circus acts' (including trapeze, high wire and acrobatic artistes as well as fire-eaters and knife-throwers) as well as such singers as Dusty Springfield, The Everly Brothers, Paul & Barry Ryan, and Liza Minnelli; pop and rock bands that included The Zombies, The Searchers and, rather aptly, The Animals; marching bands and dance troupes; a scattering of veteran variety performers; and the odd figure paying tribute to the London music hall (such as the seventy-two-year-old Arthur Treacher, who had made his name in Hollywood playing English butlers, performing the song Knocked 'em in the Old Kent Road).

The plan had originally been for the recordings to be shown more or less simultaneously in the US and the UK, but, with some minor technical problems still arising in terms of the black and white production, the British would have to wait until the end of September to start watching the series, while the US colour version went out as scheduled.

The first edition of Hippodrome, hosted by the comedian Jack Carter and featuring, amongst others, the sketch performer Frances Dean, singer Jane Morgan and Gerry and the Pacemakers, thus reached American screens on 5th July 1966 and proved a huge hit. Topping the coast-to-coast ratings that night with a 40.6% share of the available audience, it sent a message back to Rediffusion in Britain that it was ringing all the right bells.

The circus acts, it seems, were particularly popular - news which was greeted with some ambivalence on this side of the Atlantic. While the people at Rediffusion were pleased that their original 'mixed genres' idea seemed to be working so well (the second edition did similarly impressively), they were aware that the circus aspect was causing some problems behind the scenes.

The animals had actually been a source of anxiety right from the start. What had obviously looked on paper like a 'fun' element of the production had proved - hardly surprisingly - to be rather less fun in practice.

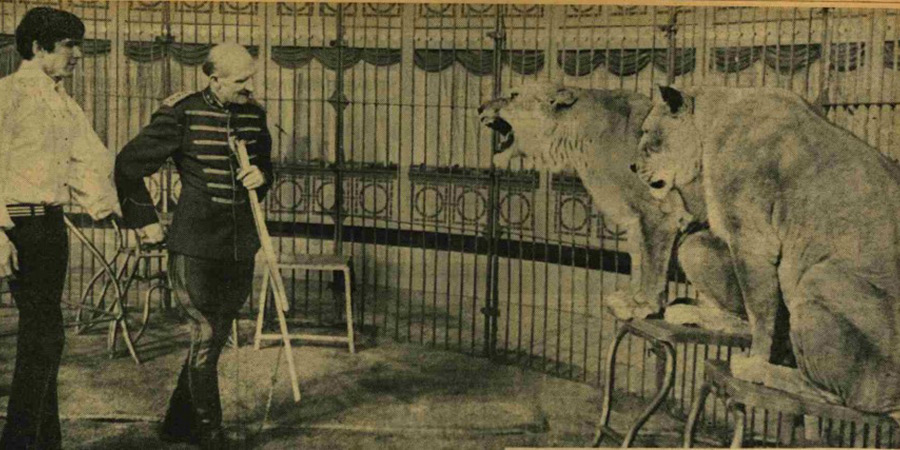

One problem was the fact that the animals were - in spite of the various trainers' claims to the contrary - occasionally unpredictable. When, for example, the eponymous leader of The Dave Clark Five decided, during rehearsals, to spend his tea break accompanying 'Captain' Sydney Howes inside his lions' cage, the less-than-friendly reaction of the 'forest bred' creatures - who immediately bared their teeth and roared at him - for some reason took him by surprise, and, now ashen-faced and jelly-legged, he needed to be dragged backwards to safety, and could barely lift a drumstick for the rest of the day.

Another problem was that, as the studio floor was hard, smooth and shiny, most of the animals - especially the larger ones - were in danger of slipping over and potentially not only injuring themselves but also harming the humans. This necessitated the creation of a whole range of bespoke rubber hooves and shoes to minimise the likelihood of a horse or something even bigger crashing over on camera in the middle of a routine.

One other hazard was, literally, not to be sniffed at. The animals had a tendency before, during, and/or after performances to deposit rather large coils of dung all over the place, which, once the super-strong lighting started heating things up, caused more than one vocalist to fight the urge to gag while they sang, and left dancers demanding a faster stage clean-up service. Even before the introduction of the kangaroo, therefore, those who were on the studio floor close to all the flesh and fur were already starting to dread the presence of each new animal's arrival.

Then came the third show in the series. This is where Woody Allen came in.

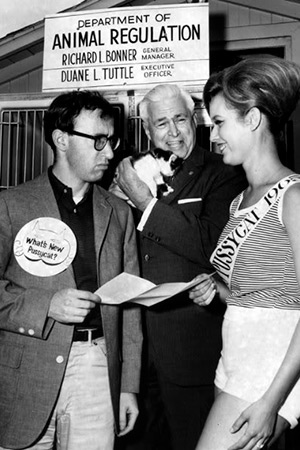

Allen was a 'no brainer' signing for Rediffusion, seeing as he was an established figure on American TV and he was currently spending some time in London, so he was convenient and relatively cheap to hire. It was also the case - as unlikely as it might now seem, given his subsequent semi-reclusive auteur status - that, at the time, he was considered within the industry to be game for just about anything.

In actual fact, Woody Allen himself, even in those days, did not consider himself game for just about anything. His management, however, most definitely did.

His management consisted of Charles Joffe and Jack Rollins - serious operators who were determined to maximise the potential of each and every client. Having practically bullied the shy scriptwriter that Allen had originally been into an inspired if chronically nervous stand-up comic, they were continuing to push him into areas and arenas where, regardless of his own current uneasiness, they insisted that he needed to go. 'Don't think about it,' they kept telling him. 'Do what I tell you.'

The result was that, by the mid-1960s, he had been thrust on to practically every major game, panel and talk show on mainstream US TV, including guest appearances on What's My Line?, The Ed Sullivan Show, The Jack Paar Program, The Steve Allen Show, The Andy Williams Show, The Merv Griffin Show, Candid Camera and Password.

Some of these shows merely obliged him to do a short stand-up spot, which he had found stressful enough, but the odd engagement had taken him much further outside his comfort zone and forced him to share the screen with animals. Famously 'at two with nature', Allen, even in those days, was uncomfortable enough sharing the same planet as animals let alone a studio ('I don't like being bitten and I hate being shed on, licked or barked at'), but, thanks to the cajoling from Rollins and Joffe, he had winced his way through several 'comic' spots with a variety of other creatures.

In 1964, for example, he had been prodded on to I've Got A Secret - a popular US panel game in which celebrity guests had to guess the hidden quality, craft or quirk of each contestant - where he was forced to attempt to sing a duet of Little Sir Echo with a poodle called Michelle, a painfully unfortunate routine which, in spite of much rehearsal, reduced the highly-trained dog to a whining wreck, and Allen to a fist-clenched ball of tension. By this time, however, Allen had been convinced by his managers that, if he wanted to earn the right to autonomy in the long term, these kinds of ordeals would have to be endured in the short term.

In the spring of 1966, therefore, he was still forcing himself to jump through some unwelcome commercial hoops. Having finished work in France on the movie What's New Pussycat? (1965) - which he had hated - he was currently dividing his time between beavering away in a hotel room in Paris, where he was (very reluctantly) writing a comic English screenplay for a non-comic Japanese movie (which would be released later that year under the title What's Up Tiger Lily?), and relaxing in London (where he was waiting to start work on the James Bond spoof Casino Royale - which he would later dismiss as 'one of the worst, dumbest wastes of celluloid in film history').

Depressed by his lack of control over his first couple of forays into movies, he was seeking any and all forms of distraction by immersing himself in the night life of what was now being called 'Swinging London'. His unusual amount of free time also meant that he was available for the odd UK TV engagement, and (as it was still his managers' wish that he 'seeped into the pores of the multitude') he popped up during this period on a number of British shows, including Tarbuck At The Prince Of Wales, Dusty and The Eamonn Andrews Show.

He agreed to host an edition of Hippodrome - a programme which he had never seen - mainly because he was told that it would be shown back in the US, where he needed some publicity to promote his forthcoming debut play on Broadway, Don't Drink the Water. It would be an unusually tightly-packed as well as eclectic episode, featuring, amongst others, the Canadian comic Libby Morris, Germany's singing and dancing Kessler Twins, trapeze act The Flying Armors, The Kneller Hall Trumpeters and Dubsky's Football Dogs, as well as the light-hearted Mancunian pop group Freddie and the Dreamers.

As for what Allen would be obliged to actually do on this show, he was only informed, during the initial conversation, that it would involve a stand-up spot and some brief links introducing the other acts. 'Oh yes,' it was added blithely, 'there might also be a tame animal or two.'

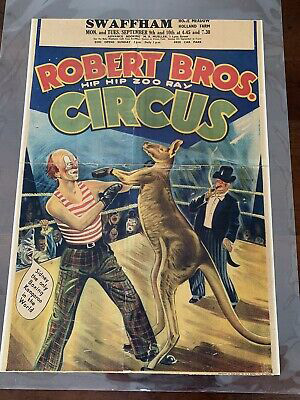

This is where the kangaroo came in. The kangaroo in question was called Sydney, and he was part of the Robert Brothers travelling circus.

The Robert Brothers (whose family had been in the business for the best part of two hundred years) were the main suppliers of animals for Hippodrome (the others came from the Danish-based Cirkus Benneweis). Among the many 'acts' on their roster was a herd of baby elephants; a group of performing bears; a Scottish dog revue; a drift of pigs; several zebras and llamas; some Shetland ponies; a troupe of 'comedy' chimpanzees (Jacko, Rabbit, Bobo and Junco); a 'mixed group' of lions, leopards, tigers and pumas; and Herman the Dancing Horse.

The circus had been featuring a boxing kangaroo since the early 1950s (continuing a tradition that itself dated back to the late Victorian era), when an earlier incarnation of 'Sydney' (billed as 'The World's Only Boxing Kangaroo') had travelled the world starring in a seemingly endless succession of brief bouts with trainers and clowns. This latest Sydney was, like most kangaroos, quite placid unless provoked, but he had been known to get somewhat excitable under the lights, and only recently, during a performance at Liverpool's Wooky Hollow Club, had given one blue-and-white-scarfed spectator in the front row a black eye.

When Allen was, somewhat belatedly, informed by the Hippodrome producer, Peter Croft, that he would be expected to take part in an 'hilarious' comedy boxing match with a kangaroo called Sydney, he merely sighed and shrugged his shoulders. It was, he felt, just one more pothole to shudder over on what felt like the long road to hell.

It would, however, be rather worse than that. It would prove more of a sinkhole than a pothole.

When the show went out on air (19th July in the US, 10th October in the UK), it started innocuously enough with Allen striding out confidently, telling a few jokes and then introducing the first act. His return, to tell another comic story and introduce another act, also went smoothly and successfully.

Then, however, the nightmare started. Allen reappeared, after a commercial break, still bespectacled but now dressed in a white vest and red shorts. 'It's generally known to the public that I'm a guy who can handle his fists pretty good', Allen deadpanned to the audience. 'Tonight, on Hippodrome, you're going to watch me fight the Australian light heavyweight champion.'

He then stepped into the newly-assembled boxing ring and was confronted by Sydney, who was sporting his own bespoke boxing gloves for the occasion, along with his rather oleaginous-looking trainer, who was posing as the referee.

It was clear more or less immediately that Allen had not the slightest desire to go anywhere near the kangaroo. It was equally clear that the poor kangaroo (which, apparently, had already been slightly spooked after being kept waiting in a malfunctioning lift) had not the slightest desire to go anywhere near Allen.

Allen was probably keenly aware that whatever he might be tempted to try, by way of comic gesture, to get some laughs would also be likely to alarm and antagonise the animal into some kind of retaliatory action. Torn as a consequence between favouring personal safety and audience silence or personal danger and audience laughter, he proceeded to oscillate nervously between one extreme and the other.

Demonstrating some decent fighting footwork, he reached in a couple of times to pat the animal gently on its chest, tried a kind of comic pirouette around it, and then vaguely waved a glove at it. This last gesture seemed to trigger the trained response from the kangaroo, who suddenly lurched forward with both gloves leading, alarming Allen sufficiently that he raced backwards into the ropes.

The trainer, having just been given the nod by the studio manager to speed things along, started pushing Allen straight at the kangaroo, which seemed to distress both parties in equal measure. Allen responded by dodging the trainer and opting for an attritional strategy that kept him as far away from the animal as possible, but still the trainer kept trying to engineer a brawl at close quarters.

Eventually, and in the only truly enjoyable moment of the entire encounter, Sydney the kangaroo finally snapped, first hitting the trainer in the chest with both fists and then leaping up and kicking him hard and fast in the marsupials, sending him flying straight out of the ring flat on his back. Allen, upon seeing this, seized on the opportunity to flee as quickly as possible, climbing out between the ropes to safety.

The show then cut to a commercial, and returned with The Kneller Hall Trumpeters heralding another, much more conventional, colourful act. It must have seemed, to some of those who were watching, as if the past few minutes had been a very peculiar dream.

The most surprising thing about the public reaction the following day, however, was that there was hardly any reaction at all. In America, apart from one reviewer's bizarre observation that he had found the kangaroo to have been 'obnoxious', there was no public comment whatsoever. It would be much the same in Britain: one critic, lamenting the waste of Allen's talents, judged the routine 'somewhat pathetic', while a reader wrote in to complain that 'whoever suggested that sketch should be made to do ten rounds with Cassius Clay', but that was all that the incident elicited.

Perhaps it was assumed that such mistreatment of an animal was simply the kind of thing that often happened in a circus, or perhaps it was assumed that such mistreatment was the kind of thing that happened on a television show that combined circus and comedy elements, or perhaps, at the time, surprisingly few people actually regarded it as mistreatment at all. What little that we do know is that the episode performed well enough in the ratings, attracted plenty of positive comments, and retained much the same size of audience for the following week's instalment.

Hippodrome, as a series, ended up making a huge amount of money for Rediffusion, and not only earned it several more lucrative commissions from a grateful American network but also encouraged many more British programme-makers to start exploring, and exploiting, the technique of colour television in their own country. It had been a rash and risk-laden project, with its awkward mix of styles and sources, but, as a gamble, it had paid off rather handsomely, and, in that commercial context, any critiques counted for far less than the coins.

As for the two participants in that most peculiar of boxing bouts, they would both go on to experience interesting times. Sydney the kangaroo continued being pushed and prodded into action for the benefit of his circus and studios until, in the early 1970s, he was finally retired and left to live out the rest of his days in peace. He was replaced by a younger kangaroo called 'Skippy', who in turn would bounce and box his way through innumerable contests in the circus, including for special seasonal events that kept on being filmed for British television right through to the 1980s.

Eventually, however, the appetite for such an act started to decline, and had faded out completely long before the Wild Animals in Circuses Act of 2019 finally made the practice illegal in UK venues. Skippy, mercifully, would be the last kangaroo in Britain to be shoved inside a boxing ring.

Woody Allen, meanwhile, eventually persuaded his managers that he was much the better judge of what suited his particular talents, and that led to him being given complete control over each new project, and so the awkward TV spots were replaced by some of the greatest comic movie masterpieces of the next few decades. It would only be late on in his life that, ironically and highly improbably, he would find himself having to fight in public once again, but this time not with kangaroos but rather a succession of kangaroo courts.

As for Hippodrome, in colour and black and white, it slipped away swiftly from memory, a sobering example of what can sometimes result when television allows itself to be motivated more by commerce than conscience. Sometimes you get monkey tennis. Sometimes you get kangaroos and comics. Sometimes you get The Jeremy Kyle Show. The lesson, alas, seems destined never to be learned.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more