I can't talk now, 'cos he's here: The true story of Peter Cook's Where Do I Sit?

It is often said that a genius without a flaw would be insufferable. In that case, it is fortunate that Peter Cook was responsible for the talk show Where Do I Sit?.

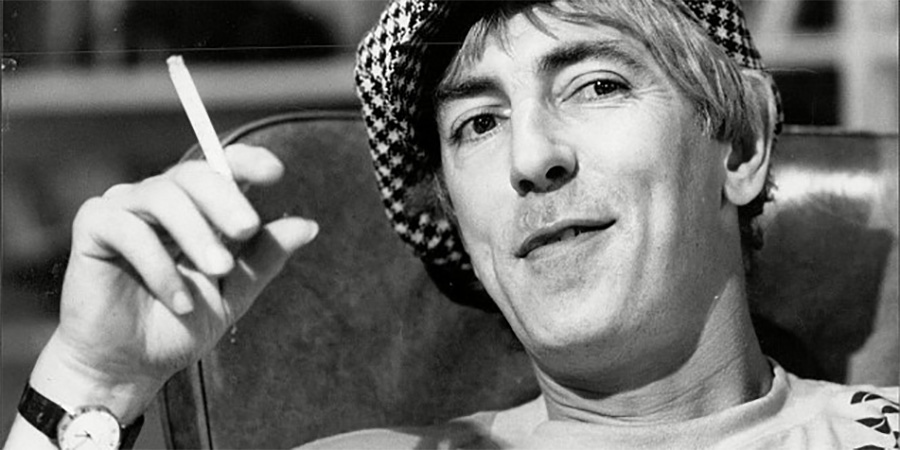

Up until Where Do I Sit? in 1971, Peter Cook had not taken a wrong step. He had written some of the funniest and most beautifully structured sketches and monologues in the history of British comedy (including 'One Leg Too Few' and 'Interesting Facts') while still a teenager; he had scripted two West End revues (Pieces Of Eight and One Over The Eight) while still at university; he had been lauded in London and New York in his early twenties for being part of the satirical quartet that staged Beyond The Fringe; he was also, by his mid-twenties, running a night club (The Establishment) and a magazine (Private Eye); and, in partnership with Dudley Moore, he had made some of the wittiest British comedy TV series (Not Only... But Also...) and movies (Bedazzled) of the 1960s.

So why, at the start of the 1970s, did he decide that the time was right for him to become, of all things, a talk show host? There were three main reasons: the pausing of a double act, the stalling of a solo act, and the arrival of an opportunity.

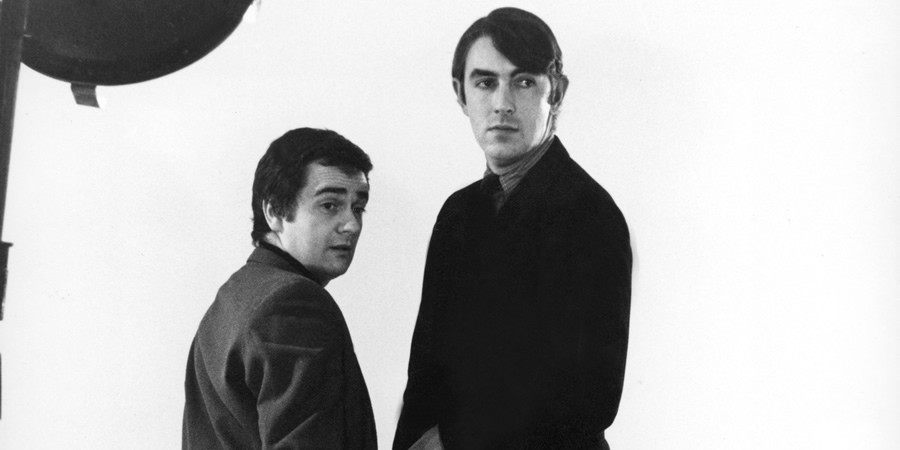

In terms of the double act, he and Dudley Moore had recently come to the conclusion that they needed to spend some time apart. Although they had worked together on a third series of Not Only... But Also... for the BBC in 1970, their relationship had grown somewhat tense. Moore, resenting being seen by some as merely his partner's 'glove puppet', had oscillated between rebelliousness and lethargy throughout the production, while Cook, in response, had drunk too much and written too little. The double act badly needed a break.

Cook had hoped that a solo venture as the star of a movie, The Rise And Rise Of Michael Rimmer (which also came out in 1970), would provide him with another semi-regular outlet for some of his many comic ideas, but he was disappointed by the reaction it had received. Although its satirical bite would later be far better appreciated, at the time it had left some critics cold, and the poor performance at the box office was enough to get his next film project quietly dropped.

The arrival of an opportunity, however, came because of the BBC's ongoing search for another talk show host who could fill the hole in the schedules left by Simon Dee. Having tried and failed to persuade the Corporation to give him a hefty pay rise, Dee had defected to the newly-formed London Weekend Television at the end of 1969. Most people at the BBC had not been sorry to see him go, thanks to his record of rows and ego-driven demands, but his show - Dee Time - had been extremely popular, especially with younger viewers, and it was deemed important to find a strong replacement.

Roger Moore had been sounded out - and offered, by BBC standards, a generous salary - but he eventually passed on the opportunity. Derek Nimmo, on the other hand, was happy enough to try his luck, and his series If It's Saturday, It Must Be Nimmo was broadcast during 1970.

Nimmo, after a slightly shaky start, had fared quite well, but he had been forced to record the shows during the same period in which he was starring in a West End musical, and the strain of dashing back and forth between his two commitments had left him disinclined to repeat the experience. There was, as a result, still a vacancy at the BBC for a new talk show host, and Peter Cook, much to the surprise of many of his friends and colleagues, was keen to fill it.

His decision surprised them simply because, as he was such a naturally entertaining interviewee, it struck some as rather perverse to attempt to be an interviewer instead. Cook, however, was determined to test himself in a new role.

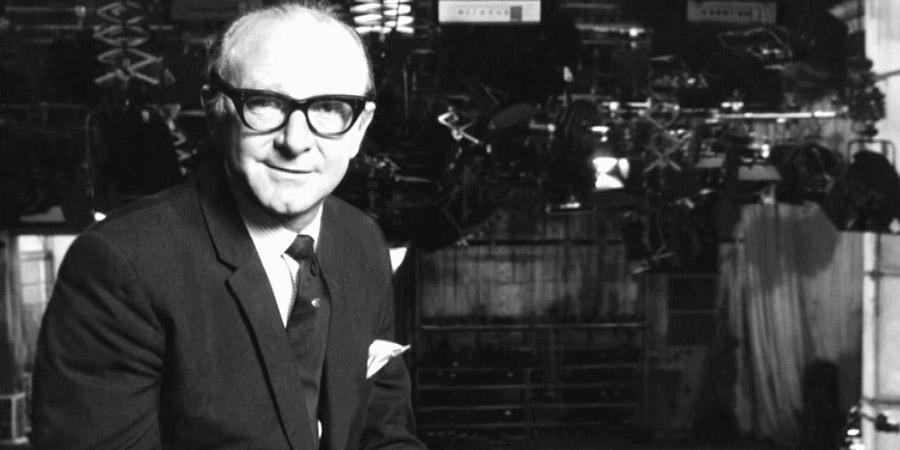

He was ready to do so because Michael Mills, the BBC's Head of Comedy, had been so eager to work with him on a project. Mills had not initially thought of a talk show as that project - he had merely made it clear that he was willing to consider anything Cook might propose so long as it fitted into the Comedy Department's remit.

Cook had then set his own conditions: he was not interested in collaborating again with Dudley Moore any time soon, and he was not interested in doing anything remotely Beyond The Fringe-like and overtly satirical. Basically, he did not want to repeat himself.

He wanted to do something new, something different and something dangerous. He wanted to do live television, where anything could happen. He wanted to be funny but sometimes serious, he wanted to be free to improvise and also to feature certain pre-recorded sequences - and he wanted some interesting guests with whom he could chat and interact. What essentially he wanted to do, he told Mills, was to reinvent the television talk show.

Mills was ready to back him. For one thing, he could see that such a series had the potential to be just the kind of exciting and edgy format that the BBC needed to start a new decade, and, for another thing, he believed that Cook was a genius and was therefore disinclined to doubt him.

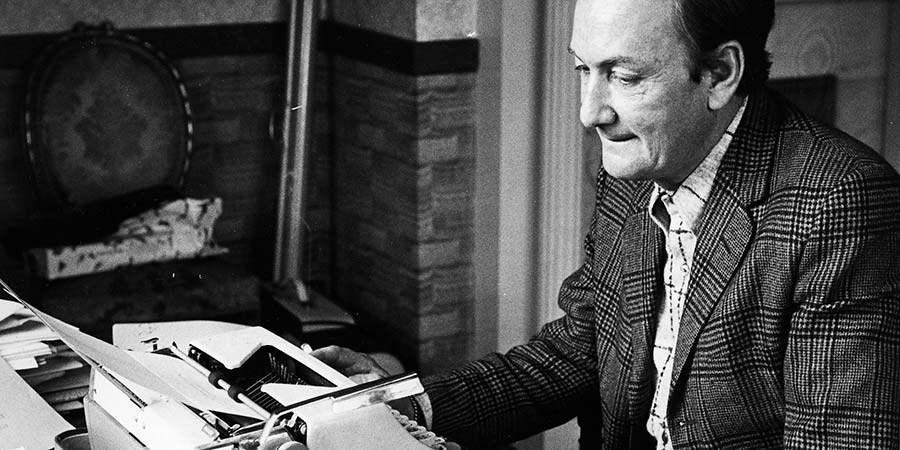

Mills's own boss, the Head of Light Entertainment Bill Cotton (pictured above), was nowhere near as sanguine about the idea. 'The alarm bells went off in my head as soon as he came to me with it,' Cotton would later tell me. 'I mean, Michael was a very good friend of mine, and he usually had great judgement, so I really didn't enjoy questioning him about this, but I had to and did make clear my reservations. But Michael was so adamant it was going to work, and he had a track record that had more than earned my respect, so I didn't stand in his way. He sort of convinced me.'

With the twelve-episode series now commissioned, Mills started working with Cook on the preparation. The young producer/director Ian MacNaughton, fresh from overseeing the first two series of Monty Python's Flying Circus, was drafted in to direct the show, and, at the start of 1971, they began filming the short sketches that would be inserted into each live episode.

Among these items was a strange encounter at a Batley petrol station that saw Cook emerge dressed as Cilla Black to badger a succession of startled and in some cases aggressively unamused Yorkshire motorists. Another scene saw him with a noose around his neck on Ilkley Moor, while a third had him lying across a brook in Black Park, Wexham, while his girlfriend Judy Huxtable used him as a bridge. He also filmed some sights and scenes with a view to using them during whatever pop song that, bizarrely, he had somehow managed to persuade MacNaughton that it would be a good idea for him to sing - live in the studio - each week.

When it came to planning guests, Cook made it clear that, along with a few of his own preferred celebrities, he would also welcome anyone off the street whom the production team thought might prove interesting. The key thing, he said, would be to do without the usual research and 'pre-interview' chats so that the conversation on the night would be spontaneous and unpredictable.

The first test of all of this came on Friday 19th February, at 9:20pm, when the first episode of Where Do I Sit? reached the screen with a sparse set that one observer likened to 'a gymnasium furnished by Habitat'. Dudley Moore, in supportive mood, was in the front row of the audience, shouting out 'Where's your mate?' at the start, and Cook made his entrance dressed as Henry VIII before discarding his costume and introducing his first guest, Stanley Unwin, who responded reassuringly enthusiastically, in his trademark 'Unwinese', to some questions about decimalisation, Rolls-Royce, Concorde and the Common Market.

Things continued to flow fairly well when Cook turned to his second guest, his Private Eye colleague Auberon Waugh, who made a few barbed comments about various politicians before he was interrupted by some badinage between Cook and MacNaughton up in the gallery.

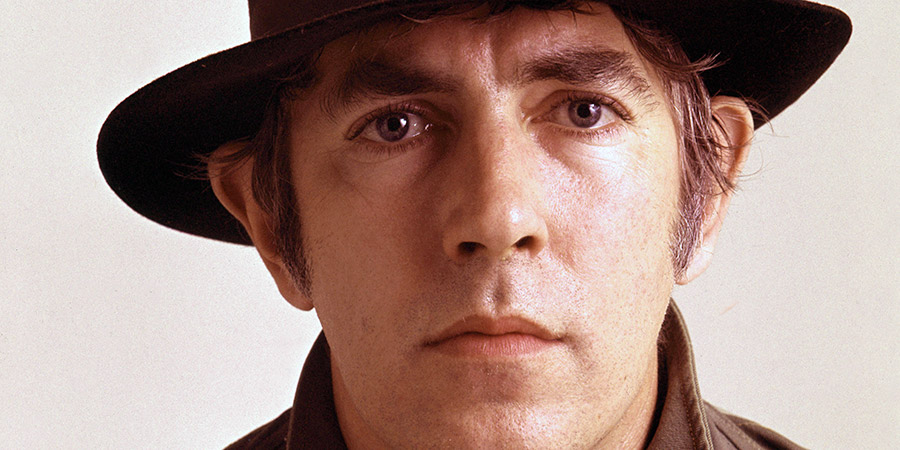

It was only after this that things really started to go badly wrong. They went wrong because Cook now had to 'interview' the veteran American humourist S. J. Perelman (pictured below).

The expectation had been that this distinguished writer, whom Cook greatly admired, would settle down and casually pluck a few tried and tested anecdotes from his huge fund of experiences (as a writer for the New Yorker magazine and the co-author of several Marx Brothers movies, along with many other notable achievements) and chatter away more or less unaided. The reality was that, by this stage in his life (he was sixty-seven but acted a decade older), he was inclined to say nothing much and then quietly doze off.

American broadcasters, who were already quite used to avoiding this ordeal, would no doubt have warned the BBC team not to use him, but - thanks to Cook's 'let's just wing it' philosophy - no one on the team had bothered to check. The consequence was that, after eliciting nothing much more than a dozy grunt or a dazed stare with his first couple of questions, the host - for possibly the first time in his life - was paralysed with anxiety. With no research notes on which to draw, and no prepared questions to work through, Cook (who would later confess to feeling 'a gathering sense of panic and futility') could do nothing but squirm in extreme discomfort. 'It was terrible, terrible,' the watching Auberon Waugh would later say. 'Oh it was awful.'

As if this was not bad enough, Cook then decided to go ahead and close the show with what he described ominously as his regular singing spot. This first week, he chose to sing a Johnny Cash song in the style of Johnny Cash. 'It was really awful,' said Cook's old friend Willie Rushton, who was watching the horror unfold at home. 'Nobody knew whether he was joking or not. It just wasn't working and he knew it. What you could see was a man who was not entirely happy about this particular period of his life, who'd embarked on a dreadful idea.'

Once it was all over, a sweat-soaked Cook staggered off to the BBC bar, where, determined to put on a brave face, he lit up a cigarette, knocked back a few whiskies, and had everyone laughing at his account of just how appalling the whole thing had been. Inside, however, he was deeply embarrassed and unnerved.

The reviews in the next morning's newspapers were, on the whole, devastatingly negative. The always irascible Christopher Dunkley, writing in The Times, held nothing back, slamming the 'endless weak jokes about the technical trivialities of television production', including frequent shots of producer Ian MacNaughton in the production gallery telling Cook what to do next. Dunkley went on to complain about the '"Ho, ho, very satirical!" screen captions', the 'truly pathetic' Perelman non-interview and the 'dismally embarrassing' other elements of the show. The critic was even angry that Cook knew a few of the people who featured on the show: 'The whole thing reeked of an old boy's get-together'.

It was much the same elsewhere. Only The Stage (headline pictured) strained to be sympathetic, arguing that the fact that 'you never knew quite what was going to happen next' should be seen as a 'commendable feature', and the show as a whole was worthwhile 'if only for the fact that the programme made a definite attempt to get away from the standard variety show format'.

Things were even worse behind the scenes at the BBC, where Bill Cotton was in a furious mood - mainly with Michael Mills:

I'd watched the first programme and felt like cancelling the whole deal then and there. Honestly. I thought it was that awful. I mean, don't get me wrong, I thought Peter Cook was a genius, just like Michael did, but unlike Michael I knew he wasn't suited to being an interviewer. He just wasn't. He didn't do any preparation, he rambled, he asked really silly questions, he didn't listen to the answers, he seemed to get distracted by what was happening off camera. He was all over the place.

The truth was that the shell-shocked star was in an even worse state after that first show. As Judy Huxtable later revealed to his biographer Harry Thompson:

He had thought that a chat show would be a piece of cake, and didn't realise until after [the opening episode] that it wouldn't suit him; but by then it was too late and he had to go through with it. Peter was a very proud man and he couldn't handle the stress of realising that he couldn't do the show. The emotional odds started to bank up against him. He was drinking too much, and abusing prescription drugs. In fact, he was using a whole cocktail of drugs to cope, mixed with alcohol.

It was this vulnerability that, for better or worse, saved his show - at least for the time being. As Bill Cotton later told me:

I called Michael [Mills] into my office and let him know exactly how I felt about what had happened, and said I was strongly inclined to take the programme off the air. But he told me that Peter was currently in a very fragile psychological state, and the humiliation of having his show cancelled after just one episode could destroy him. So I agreed to hold back, and Michael assured me they'd turn it around. I very much doubted that, but what else could I have done?

The team around Cook, to be fair, did make an effort to pull the programme away from the edge of the cliff, but they could do little about their self-medicating star, whose moods were twitching up and down at a manic rate. He was being given research notes now, but he didn't seem to be reading them, and meetings usually came and went without him contributing much other than huge plumes of cigarette smoke.

When the second episode arrived, therefore, it came as no real surprise that the star had failed to learn any lessons. The guests this week were Kirk Douglas, Johnny Speight and Spike Milligan, and it would not take long before all three looked as if they'd rather be elsewhere.

The encounter with Kirk Douglas was only saved from being a complete disaster because of the fact that the Hollywood star, being such a fan of Cook, did all that he could to remain looking affable in spite of the scarcity of questions. It started badly enough - when Douglas walked on, a glazed-eyed Cook shook his hand and, instead of saying the intended 'How are you?', heard himself instead saying, 'Who are you?' It then got progressively worse as Cook slowly slurred himself to a stop.

Cook's fellow comedy writer Johnny Speight (pictured) was on next. Speight was the kind of character who would talk even if no one asked him any questions, so there was no problem here with awkward silences. The problem this time was more to do with the fact that Cook was slurring very quickly often at the same time that Speight was stuttering even more quickly, so much of what was said was barely comprehensible to the audience.

Another element of the show was a sketch, featuring Cook and Spike Milligan dressed as tramps, which began like this:

MILLIGAN: Are you a German tourist?

COOK: No, I'm God.

MILLIGAN: You're Goad?

COOK: No. I am God.

MILLIGAN: Eric God?

COOK: No. God.

MILLIGAN: Well, how was the universe made?

COOK: Fell off the back of a lorry, didn't it?

This would enrage the watching 'moral guardian' Mary Whitehouse sufficiently to make her telephone the Chief Constable of Worcestershire and demand that he prosecuted Cook for blasphemy.

It was a fairly amusing routine, but once it was over Cook again showed his naivety as a host by asking the audience if anyone had found it offensive, mocking the inevitable camera-hungry character who answered in the affirmative, and then asked with a grin if anyone had phoned in yet to complain. It was probably only his nervous way of trying to make light of his own feelings of being in the middle of a blizzard of criticism, but Whitehouse would seize on it as evidence that 'he quite deliberately taunted viewers'.

Milligan was arguably the last kind of guest the show needed at this stage in its troubled production. His sudden digressions, interrupted by his own sniggering, only made an already disorganised show even more of a mess. To make matters worse, Cook then insisted on 'singing' another song, which somehow managed to sound more painfully ill-judged than the previous week's sorry effort.

The reviews were, if anything, even worse than they had been for the first week - and now they were noticeably more personal, too. 'Far from being funny or original,' one critic snarled, 'I find him silly, offensive, puerile, egoistic, childish, arrogant, spoiled and aggressive - though not necessarily in that order.' Another opined: 'The humour of Peter Cook is an acquired taste, but I doubt if many will acquire the taste as a result of his Where Do I Sit?. On the basis of the first two offerings, the show is a non-runner in the popularity stakes and I would doubt whether it ever will be repeated on BBC1, let alone merit a second series.'

Bill Cotton, once again, was exasperated by what he had seen, and once again came close to pulling the plug:

I talked to Michael again. I mean, the second show, it was an utter shambles. So we had the same exchange all over again, at a slightly higher volume, with me saying how terrible it all was and Michael defending his team. And at the end of it, I said, 'No, we'll pack it in'. And Michael said, 'No, no, I know I can get it right'. I said, 'You won't get it right, Michael. I mean, he just can't do it.' Peter was the best guest in the world on a chat show, but, you know, he wants to talk, he doesn't want to listen. So I said this, and again Michael really pleaded with me to give them more time. And so, in the end, I agreed to let it go again. Three times!

The third episode duly went out on Friday 5th March. The guests on this occasion were the academic and feminist Germaine Greer, the director and satirist Ned Sherrin and (promoting her forthcoming appearance in Sherrin-produced movie Up Pompeii) the actor Julie Ege.

Even before the show had started, it was clear to Sherrin, who knew Cook well, that the host was doped up to the eyeballs. 'He was in a terrible state', Sherrin later recalled. 'He was frightened. It was chaos.'

At one stage in the programme, Cook, now sailing as close to the wind as possible, revealed that, after the previous episode, one angry viewer - a Mr Wentworth - had written in to complain that the star was 'clearly a drug addict'. He then announced that he had decided it would be a good idea to have it out with the man by calling him up live on air.

The audience then watched and listened as Cook dialled the number and waited. Someone answered, but it was the complainant's wife:

COOK: Could I speak to Mr Wentworth, please?

MRS WENTWORTH: Ooh, I'm very sorry, but Mr Wentworth is in the bath.

COOK: Well, this is Peter Cook speaking. He just wrote in to the show and said I was a drug addict, and I'd like to talk to him.

MRS WENTWORTH: Ooh, fancy that! Well, I'll just see if I can get him out. Are you on at the moment?

COOK: Yes.

MRS WENTWORTH: I'll just switch on the telly to see if we are on, you know. It takes a little time to warm up. [Shouts] George!

MR WENTWORTH: [From a distance] What?

MRS WENTWORTH: It's Peter Cook on the line! He says you said he was a drug addict!

MR WENTWORTH: What? I'm in the bath!

MRS WENTWORTH: Well, we're on!

MR WENTWORTH: We're on what?

MRS WENTWORTH: We're on television!

MR WENTWORTH: I'm in the bath!!

There was a long silence at the Wentworths' end of the line, interrupted only by the odd scuffling sound and an opening and shutting of a door, whilst Cook sat in the studio alongside his guests, grinning at no one in particular while the studio audience whispered and giggled uneasily. Eventually, after what had felt like four times as long as it actually was, a moist Mr Wentworth finally came to the phone:

MR WENTWORTH: Who's that?

COOK: Peter Cook. You said I was a drug addict.

MR WENTWORTH: Yes, well...I was...er...lost for words. Anyway, I can't linger now 'cos I'm dripping wet. And I'd like to watch the rest of the show.

Some felt that the exchange had been too awkward to have served any positive comic purpose, while others enjoyed hearing a troll being trolled, although Cook, in his current diminished state, was left looking strangely flustered by the abrupt ending of the call. It was, in a way, symbolic of the whole series so far: the courage of the approach to a live TV show had needed to be matched by the confidence of the performance, and Cook, in this context, at this time, was simply nowhere near his normally sharpest self.

There was actually a case for claiming that there had been an improvement - the number of viewers, either out of curiosity to see train wreck TV or out of fascination to see something daring and inventive, had actually risen during the first three weeks. In critical terms, however, the format was falling to bits.

On the Monday morning after the latest episode, Bill Cotton decided that, this time, he really had to act:

After the third one I just blew my whistle and said, 'No'. I called in Michael Mills first of all. And Michael was very upset - it really was our hardest time together. And then I called in Ian MacNaughton and Peter. And of course Peter was very, very upset. And I wasn't particularly popular in some quarters - not that it worried me - because Peter had a tremendous constituency - one of whom was me. I thought he was one of the funniest men. So I hated having to go against Michael and against Peter, but it was just one of the crosses that you bore as a television executive. There are people who want to keep doing things that don't work, and you can either shrug and say, 'Well, okay, if he wants to do it'. Or you can actually earn your money and say, 'You're not doing that any more. Sorry, you can't do it. You're no good at that'.

The BBC put out an official announcement that read: 'After a great deal of consideration, we have decided that the programme was not doing the job it set out to do. We felt that we had to protect Peter Cook's reputation and that of the BBC.' Then Bill Cotton was busy again:

Peter came to my office with his lawyer. They were threatening the BBC with legal action. So I very calmly read out the standard clause that's in all the contracts, which gave the BBC the right to remove any programme from the schedules which is deemed liable to bring the Corporation into disrepute. That caused the two of them to whisper anxiously to each other, and then the lawyer asked to speak to me privately. So I took him outside and, as I'd suspected, he said that the main worry was about money. He said that Peter had already spent the sum he was due for the whole series. So I told him that Peter could keep the money for the first three programmes that had aired, and he could owe us a few appearances at a reduced fee when he was in a better mental and financial state to do so. Then we went back into my office and explained the deal to Peter, who broke into a beaming smile. Then we all went off to the bar like the best of friends.

Cook would soon slide the memory to the back of his mind and move on to other things. He would, ironically enough, find himself on the other side of the chaos, a few months later, when he and Dudley Moore appeared on a live talk show in Australia, hosted by Dave Allen, which ended up being deemed to be so out of control that all three of them ended up being banned.

The BBC would also soon move on from the episode and, turning its back on its brief age of talk show experimentation, hired a young Yorkshireman named Michael Parkinson to sit in a chair and ask questions to people who were only too eager to answer them. One of his funniest and most entertaining interviewees over the next few years would, of course, be Peter Cook.

What, then, was the proper legacy of Where Do I Sit?? One answer, which rapidly came to be set in stone as the 'proper' answer, is that it continues to serve as a salutary warning to all ambitious stars as to the dangers of doing something very different from what had made them famous. There is some truth in that, but by no means the whole truth.

What is typically ignored in most retrospective appraisals of the show is the fact that, in some ways, it was simply ahead of its time. Making a live TV show seem really live, in all its messy unpredictability, was frowned upon at the time as being shamefully unprofessional; nowadays it's regarded as 'ground-breaking'.

Attempting such unorthodox and risk-laden and uncontrollable things as calling members of the public live on air caused alarm and in some cases outrage at the time. In more recent years it has been hailed (as if Cook's show never happened) as admirably daring, innovative and refreshing. Looking to go beyond the flatly straightforward 'Q&A' talk show format was considered at the time to be perverse or disrespectful or confusing, whereas today it probably wins you a BAFTA.

In short, there was little wrong, and quite a lot right, about Peter Cook's ideas for modernising the talk show. There was just quite a lot wrong with their execution. He simply wasn't personally in the right frame of mind to realise them properly at the time.

It did not really matter. As with so many of his creative insights, they were taken up eventually by far inferior, but more consistently industrious, talents, and had their impact indirectly.

As for Cook himself, contrary to countless lazy and ignorant claims, his comic genius would keep on burning bright to the end of his life. Look, for example, at his glorious reduction of Roald Dahl ('"Ronald" is a pretty ordinary name, and until I dropped my "n" nobody took a blind bit of notice. But "Roald" makes me sound mysterious and important. If Ronald Biggs had called himself "Roald," like me, he could have got away with daylight robbery') or his brilliant multiple appearances on Clive Anderson Talks Back as biscuit tester, bore and alien abductee Norman House ('One of the problems with a bad metal detector is that, if it's really poorly made, it'll start detecting itself'), football manager and motivational speaker Alan Latchley ('Football is about nothing unless it is about something, and what it's about is football!'), judge Sir James Beauchamp ('Who better to take the law into their own hands than a judge?') and rock legend and environmentalist Eric Daley ('You won't find an anchovy going into the rainforest and saying "Let's tear it all down!"').

Cook did count Where Do I Sit?, along with saving David Frost from drowning, as a bad mistake, but the many things he got right more than made up for them. One can only be thankful that he didn't waste any more of his and our time by inviting lesser performers to speak while he stayed silent.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more