It seemed a good idea at the time #2: When Peter Gabriel met Charlie Drake

There are some stories that can leave you thinking that, yes, quite a few people, quite plausibly, would have judged that the project in question was a good idea at the time. There are other stories that can leave you thinking that probably only those directly involved would have come to that dubious conclusion. Then there are the stories - the very rare stories - that leave you wondering why even those involved could possibly have thought that something so head-scratchingly odd was a good idea at that or any other time. What follows is one of those stories.

It is a story about the rock star Peter Gabriel. It is a story about the comedy star Charlie Drake. It is a story about their strange collaboration on what both of them hoped would be a hit record.

The year was 1975. It was a year in which both men suddenly found themselves stranded, unsure of how, or where, to move forward.

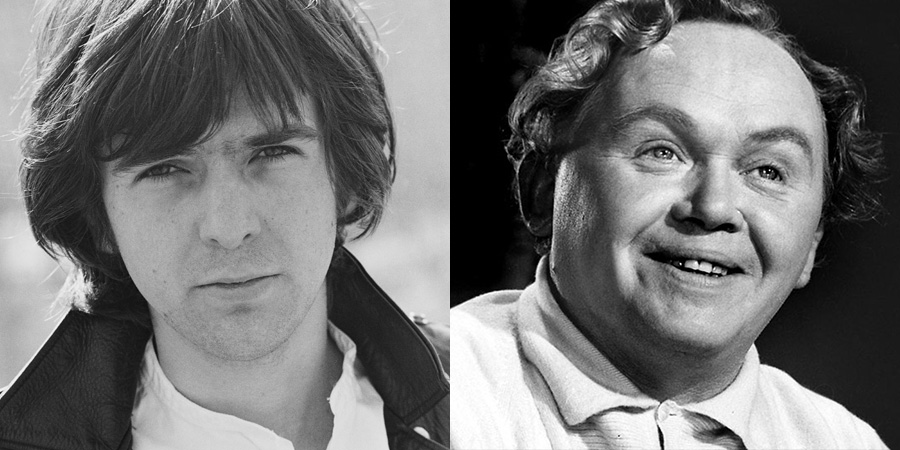

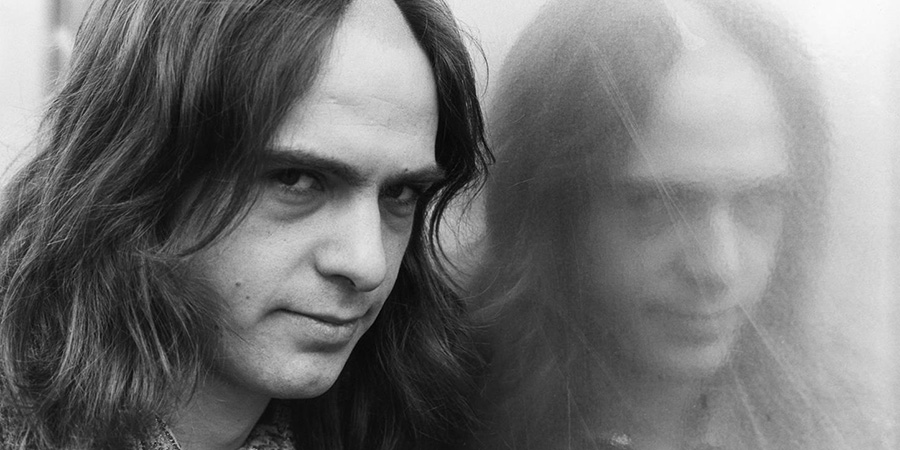

1975, for Peter Gabriel, was his first year away from Genesis - the band that, eight years before at Charterhouse public school, he had helped form and front. An imaginative writer, soulful singer and chronically inventive, theatrical and charismatic performer, he had established himself by the early Seventies as one of Britain's most distinctive musical figures, occupying an intriguingly exotic space somewhere between Jagger and Bowie.

After battling with his bandmates (especially the notoriously tetchy keyboardist Tony Banks, who was to Gabriel what Henry McGee was to Charlie Drake) throughout the period that produced the sixth Genesis studio album, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974), as well as enduring all of the anxiety that came from dealing with the difficult birth of his and his wife's first child, he had quit not just the group but also (at least for a while) the industry, in the summer of 1975, straight after a tour of the US. In an open letter sent to the music press, he declared that he 'felt I should look at/learn about/develop myself, my creative bits and pieces and pick up on a lot of work going on outside music'.

He thus intended, he said, to take a break from being 'the famous Gabriel' and spend the foreseeable future back in the privacy of his home at Woolley Mill Cottage in the village of Swainswick, north-east of Bath, doing such other things as exploring 'the hidden delights of vegetable growing and community living,' to try to 'give space to my family [...] and to liberate the daddy in me'. Now aged twenty-five, he was determined, as he later put it in the song Solsbury Hill, to walk 'right out of the machinery'.

True to his word, he devoted the next few months to distractions. He wandered in and out of some hippie communes, for example, with a view to, perhaps, moving into one of them permanently with his young family. He also took a course in the then-fashionable method of Silva Mind Control, which promised to help him reach an 'alpha state' of mental functioning, encourage 'creative visualisation' and heighten his extra-sensory awareness; he took some piano lessons, and collaborated occasionally with a number of other musicians and writers, including a football-mad Black Country poet named Martin Hall; he ate a hash cake and then recorded himself walking and talking as he tried to make his way home; he attended a few concerts (including a gig by the folk-rock band Stackridge at the Friars club in Aylesbury, where he made a guest appearance by emerging from inside a giant birthday cake); he cultivated a large cabbage patch; and, with his wife Jill giving birth to their second daughter during this period, the liberated daddy in him doted on their children.

Meanwhile, in another quiet corner of England, another public figure, Charlie Drake, was also having a year in which 'wind was blowing, time stood still'. In his case, however, it was not of his own choosing.

Drake was not exactly unaccustomed to unconventional years - he had long had an unfortunate habit of injuring himself, or otherwise incapacitating himself, as well as clashing with anyone he perceived to be infringing on his creative freedom, which often plunged him into some or other professional crisis - but 1975 was something different. It would prove itself to be a peculiarly odd time even by the standards of Charlie Drake Land.

'Charlie Drake Land' was what Charlie Drake liked to call his own little personal ecosphere. When you met Charlie Drake, worked with Charlie Drake or lived with Charlie Drake, no matter for how little or for how long, you were, in his eyes at least, an inhabitant of Charlie Drake Land. Thanks to his volatile temperament, most of these stays were normally on the short side, but, while one was there, he took your presence as a sign of exceptional good character ('It takes a lot of courage,' he would say, 'to enter Charlie Drake Land').

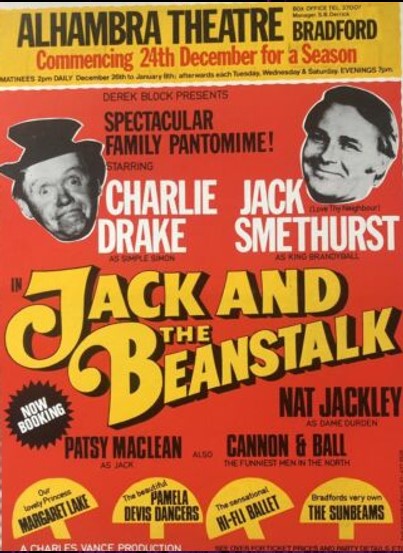

Drake (now on the verge of turning fifty) had expected to start 1975 sharing Charlie Drake Land with, among others, Jack Smethurst (then riding high in the ratings as the star of the ITV sitcom Love Thy Neighbour), the veteran variety comic actor and eccentric dancer Nat Jackley, the singer Patsy MacLean and the up-and-coming double act of Cannon and Ball. The reason why they were due to be together was that they had all signed up for a pantomime - Jack and the Beanstalk at the Alhambra Theatre in Bradford - for which Drake was topping the bill.

This was supposed to be merely the first of several already-settled projects that would keep him well-paid and very busy all the way through the year. Before the panto had even started, however, things began to go badly wrong.

They began to go wrong because Drake - not for the first or the last time - acted rashly after having what he thought was a bright idea. Arriving in town at the end of November 1974, and noting the relatively modest advertising the production was currently getting, he decided that what the forthcoming panto needed, to conjure-up a little more local interest, was the gimmick of auditioning some local 'housewives' for a very minor role in the show on a wage of £40 per week.

So, using his power as the star of the cast, he went ahead, organised and judged the talent contest, and ended up awarding the part of the fairy to a twenty-year-old Leeds woman named Sue Moodie. The local press, as planned, lapped it all up, the panto was given plenty of additional publicity, and Drake felt that he had earned a pat on the back.

What he got, however, was more like a smack in the face. When Equity, the national actors' union, heard about the stunt (via a theatre employee whom the occasionally irascible Drake had already managed to alienate), and discovered that Moodie was not a paid-up member, it sent a stern message to the comedian - three days before the panto season was due to start - ordering him to drop her immediately from the production. A furious Drake, who was no stranger to battles with authority during the previous decade or so ('Rules don't exist,' he liked to say, 'in Charlie Drake Land'), flatly ignored the instruction.

Two days later, on the night of a charity preview of the production, the comedian arrived at the theatre to discover that Equity had contacted Moodie directly and insisted that she stand down without further delay. Drake, who was by this stage positively apoplectic with rage, sought her out and demanded that she went ahead with the performance.

Twenty minutes before the curtain was due to go up, Equity - outraged at such insolence - called Drake and warned him that unless Moodie was dropped it would shut the production down right there and then. Drake, digging in, responded by insisting that unless she appeared he would tear up his contract and walk out on the show. This, on the night, did the trick, and the show, along with Moodie, went ahead.

The following day, however, the same sequence of events happened all over again, and Equity, while it struggled to pursue the issue over the Christmas period, reluctantly allowed Moodie to stay on until the end of December. As it turned out, however, she left several days before that deadline, because the management, fearful of further Equity reprisals, quietly paid her off.

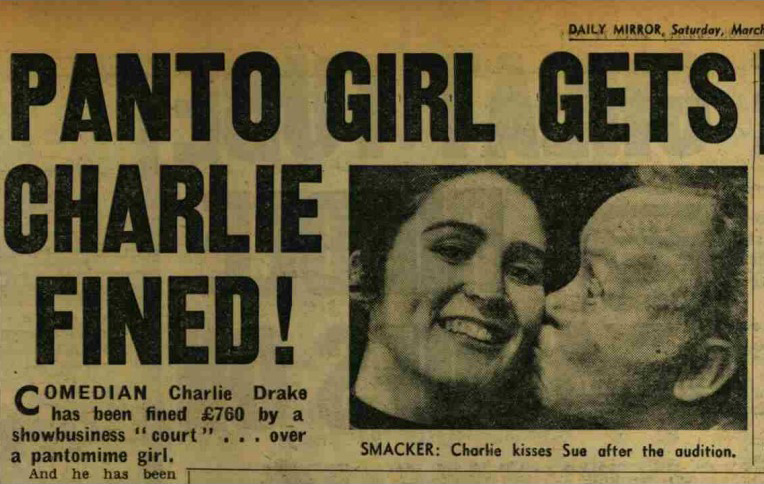

The union, however, was not yet done with Drake. Charging him with flouting Equity rules, it fined him £760 (almost £6,000 by today's value). Protesting, disingenuously, that he had been ignorant of the rule and had not received adequate warning, Drake refused to pay the sum 'as a matter of principle'.

Anyone familiar with the comedian knew where this was heading. A spectacularly intransigent man ('By far the most stubborn man,' his own manager told me, 'I have ever met!'), he had once attempted to storm out of a meeting at the BBC, only to slam shut the wrong door and find himself stuck in a cupboard. Rather than re-emerge shame-faced and admit his mistake, he stayed in there stewing for almost an hour until the room had finally emptied.

When it came to this fine, therefore, Drake made it very clear that, no matter what threats came his way, he was simply not going to pay it - ever. An angry Equity reacted by suspending him from the status of an 'approved artist'- thus banning him from working in any provincial theatre for the foreseeable future.

This wrecked Drake's entire year, because it meant that he would have to be dropped from a forthcoming summer season at the Dome theatre in Brighton, as well as a pantomime at Sunderland, along with any other performances he had planned. He could still, in theory, appear in London's West End, and also on television, but in practice - because no such work had already been contracted, and no producers had any appetite for upsetting Equity - he was effectively shut out of the whole of show business.

Straining belatedly to affect a sense of contrition, Drake did agree to attend a meeting of the union's special appeals committee in a bid to overturn the judgement, but, with grim predictability, he soon lost his temper again and vowed never to apologise and never to pay the fine. His diary for 1975, as a consequence, was wiped completely clean.

While Peter Gabriel, therefore, happily embraced the air of idleness that his resignation from Genesis now afforded him, Charlie Drake raged at what he saw as the injustice of being told to grab his things and go home. Aside from a quick trip in February to open a new branch of Monomart's DIY stores at the Battle Farm Industrial Estate in Reading ('along with the famous TV Dulux dog'), and another brief excursion in March to present a Variety Club of Great Britain 'Sunshine Coach' to the staff and pupils of Whittlesea School in Harrow, Drake was left to his own devices in what was now a distinctly empty-looking Charlie Drake Land.

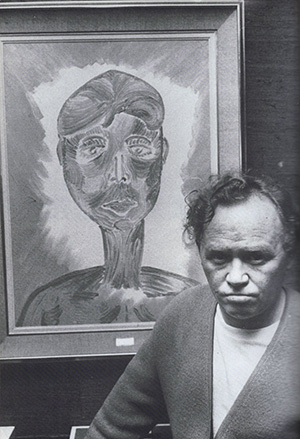

'The days stretched into weeks, the weeks into months,' he would later write about the wearing out of his joie de vie, 'and I found myself living in a desert of loneliness and boredom.' He took to painting for a while, trying to express his anger in an abstract work he would end up calling 1984. He also sat at the typewriter and struggled in vain to come up with something comical.

'I tried writing a new series for television to use when the ban was over,' he explained, 'but couldn't. Ever since I've been in the game I've worked to a deadline, and I found it hard writing something into the void.'

His mental health, as a consequence, was in danger of slipping into a steep decline. 'There was fear to be fought,' he later reflected, 'and sudden black depressions that descended in the wee small hours.' Losing the chance to perform, he said, was 'like losing your life'.

It would be music, rather than comedy, that would come to his aid. A few years before, during a summer season at Great Yarmouth, Drake had encountered a young up-and-coming record producer named Laurie Mansfield, who tried to persuade him to make an album (which was to consist of one side of classic songs and the other of audio excerpts from his popular TV sitcom The Worker). He had passed on that project, judging it too unconventional to be commercially viable (and the producer would go on to adapt the format for the 1971 LP 'Ow Do, which featured musical monologues and readings by the actor Jack Howarth, who played the famously lugubrious Albert Tatlock in Coronation Street). Drake, nonetheless, stayed in touch with Mansfield, whose 'unbound optimism, enthusiasm and sunny disposition' struck the comedian as suited perfectly to life inside Charlie Drake Land.

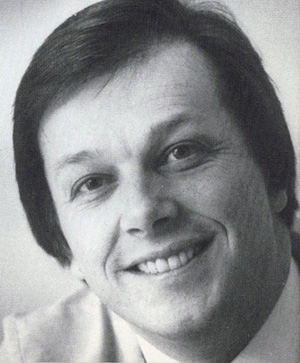

It was Mansfield (pictured, who by this time had moved on from the music business and become Drake's agent and manager) who was now doing his best behind the scenes to affect some form of rapprochement between the performer and Equity with a view to ending the damaging ban. He was also working hard to lift the comedian's sagging spirits, searching for something - anything - that Drake was still able, practically, to do.

While that could not be theatre, or television, it might still be music.

This is when something very strange happened. Say that the stars suddenly aligned, or the Fates conspired, or the eagle flew out of the night, or whatever other mystical allusion one cares to use, but, for reasons that have still not been fathomed fully, a peculiar plan suddenly came together early in July 1975. Quite independently of each other, just when Charlie Drake decided that he needed a musical project, Peter Gabriel decided to offer him one.

Why did he offer him one? Gabriel has never explained (and, alas, he was, and so far remains, disinclined to comment on this matter).

Rock stars writing for and/or producing other artists had become quite a 'thing' in popular music at that time - Paul McCartney, for example, had lent his services to the likes of Peggy Lee, Rod Stewart, Mary Hopkin, John Christie and The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band; John Lennon had produced the album Pussy Cats for Harry Nilsson; Todd Rundgren had overseen the debut of the New York Dolls; and David Bowie had co-produced Lou Reed's Transformer album and donated All The Young Dudes to Mott the Hoople and The Man Who Sold the World to Lulu - so there was nothing too curious about that aspect of the move. It was the decision to use Drake that was indubitably peculiar.

Gabriel would certainly have known about Charlie Drake for most of his life, because the comedian had been a fixture on British TV since Gabriel had been in infant school; usually playing the mischievous little misfit, the put-upon working-class Everyman, Drake's technically outstanding knockabout humour had made him one of the most recognisable comedy stars in the country, with a catchphrase - 'Hello, my darlings!' - that had been in circulation for the best part of twenty years.

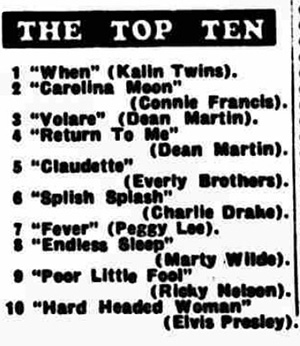

Drake was also, ironically enough, the more successful recording artiste of the two at the time, at least in terms of the singles charts. Having so far released no fewer than seventeen records (with five of them making the UK's Top Thirty, one of them - 1958's Splish Splash - peaking inside the Top Ten and another - 1961's My Boomerang Won't Come Back - reaching number one in Australia), he was far ahead of Gabriel's more album-oriented output with Genesis, whose best chart effort so far, I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe), had stalled at number 21 in 1974. 'I've had smash hits,' the comedian liked to remind people. 'Monster hits - all over the world!'

Given the pint-sized Drake's gallon-sized ego, therefore, he would probably have been mildly surprised rather than hugely flattered to be approached by this young rock star, but he certainly would have been grateful. At that stage in 1975 he would have been grateful for anyone showing him some interest.

Laurie Mansfield certainly did not hesitate to seize on this unexpected opportunity. 'Peter contacted me about it out of the blue,' he would tell me. 'It was initially via Tony Smith, who'd looked after him when he was with Genesis. I don't know if Tony had nudged him in our direction - because Tony's father was an old-time theatre man, he knew all about variety - but I do know that, by the time that Peter did get in touch, he was really very keen indeed on working with Charlie. And as for me, having come from the pop world myself, I was thrilled at the thought of Charlie Drake being produced by Peter Gabriel, let alone singing one of his songs!'

The world of prog rock was not really in the same universe as Charlie Drake Land, so the comedian, unlike his manager, had to hurry to acquaint himself with who this man Peter Gabriel actually was, what kind of music he made and what on earth he might be planning to do with him. After an uneasy listen to a recent Genesis album, and a few informative chats with Mansfield and some other younger friends, he came to suspect that what they might have in common, to some or other degree, was a flair for theatrical gestures, an affection for old English whimsy and an appetite for causing surprise. Beyond that, he really did not have a clue.

What Gabriel (above) actually had in mind for Drake was not, in fact, a bespoke piece of new material. It was merely one of three songs that he had already co-written, quite recently, with Martin Hall.

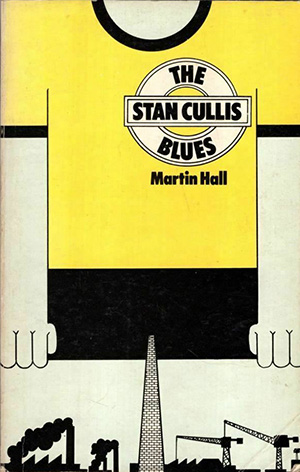

Formerly a guitarist and harmonica player in a Cannock-based blues band called The Interns, Hall - whom Gabriel had known since 1971 - had published a slim book of poems the previous year (via the literary wing of his friend's record label, Charisma) entitled The Stan Cullis Blues. Likened by one critic (more than a little generously) to the work of an English Randy Newman, it included poems about sport, Simon and Garfunkel, death, Churchill, dreams, Salisbury Plain, desire, Jimi Hendrix, concrete, James Dean, photo booths, Richard Nixon, toilets and urinals, Burl Ives and the Black Country dialect, and was praised at the time for its 'dead-pan style' and 'keen eye for the ridiculous'.

One of the characteristics of Hall's writing that most struck a chord with Gabriel was the deftly droll sense of humour that he brought to his often quirky choice of subject matter. In the title poem, for example, he described the impact of the sacking as manager from Wolverhampton Wanderers of club legend Stan Cullis as having left the whole city wandering 'round in circles/like a disallowed goal/looking for a friendly linesman'.

Another aspect that appealed were the many playful 'meta-reflections' - poems about poetry, writings about writing, poems and writings about thinking - such as the piece called 'Some Of My Best Words Are Friends', which included the lines: 'my collection of words had been broken into/abandon was missing/so was multitude/and consequence lay in pieces on the floor'.

Gabriel had so far made demo recordings of three of their collaborations. One, Get What You Want (When You Rip It Off) was a sardonic Rolling Stones parody which stuck the knife into many of those elements within the music industry that had most alienated him; another, Firebirds, was a contemplative ballad for piano, flute and acoustic guitar; and the third, You Never Know, was a waft of whimsy ('You never know/Who the honey cones/You never know/Why the hippo drones/You never know/Where the water falls/You never know/When the basket balls...') that exuded a jaunty-sounding, singalong sort of mood.

It was You Never Know that Gabriel convinced himself would serve as a suitable vehicle for Charlie Drake's distinctively squeaky, bleaty, vocal talents. He therefore dispatched a copy of the demo to the comedian so that he could acquaint himself with the lyrics and reflect on how best to stamp his signature on the song, and recording time was booked for Studio 2 at George Martin's AIR facilities, situated up on the fourth floor of a building in London's Oxford Street.

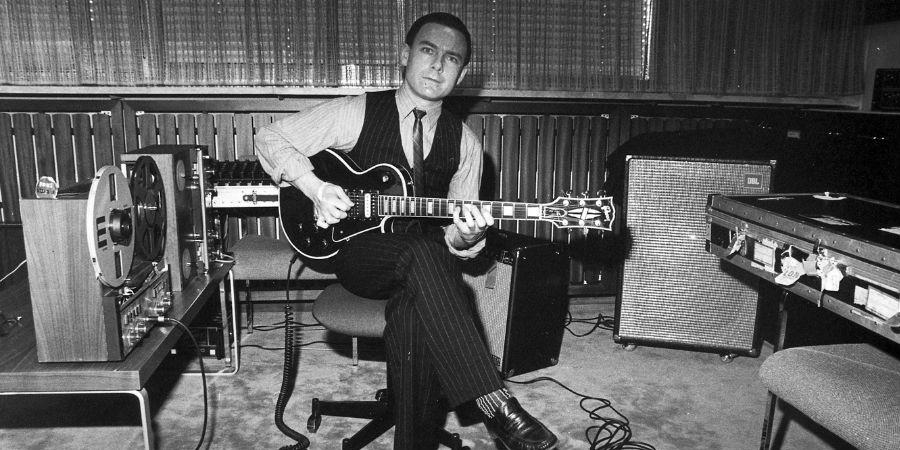

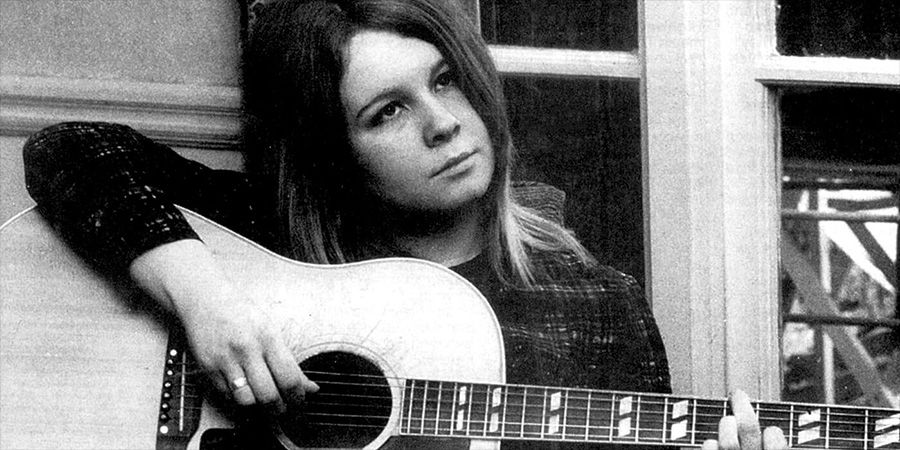

When the day came, and the musicians started arriving, it soon became clear that Gabriel, rather than treating the project in a cavalier manner, had assembled a veritable super group for the session: in through the door came Robert Fripp (above) - the founder of King Crimson and one of the most gifted and innovative guitarists of his generation; Percy Jones - a co-founder of the pioneering jazz-rock band Brand X and a hugely influential fretless bass player; Keith Tippett - a remarkably versatile and improvisational pianist; Sandy Denny - commonly regarded as the finest female vocalist in British folk-rock; and, on drums, Gabriel's former bandmate from Genesis, Phil Collins. It seems that Brian Eno, the former Roxy Music synthesiser specialist, might also have been around, possibly on the Mellotron, being brilliantly 'ambient' in some unspecified way.

It would have been an impressive line-up to support a major music star. Here, just for one day, it was on duty for the sake of Charlie Drake.

Their professionalism meant that the backing track only took a couple of hours to develop, perfect and record. Then it was Drake time.

Strolling over from The Orange pub in Leicester Square (where he had been calming his nerves), he arrived just when most of the musicians were leaving. He did not know any them, but they all knew him, and were somewhat bemused or amused by what he seems to have thought was an appropriately 'with-it' appearance. 'Charlie,' Phil Collins would later recall on his website, 'turned up with a brand new denim outfit for his rock debut... it was quite touching to see him at it.'

Inevitably, the comedian, having had time to ponder the song, had convinced himself that he could 'improve' it, and so he proceeded to embellish things with certain 'Drake-isms' (such as sudden snatches of accents - including Brooklyn, Cockney and a couple from The Goon Show - and tones ranging from childlike whines to crooner cries, as well as some ad-libs of questionable taste - given his notorious weakness for young women - involving groupies). Gabriel and his engineer (Steve Nye), probably reasoning that Drake knew far better than they did who was most likely to buy the record out there in Charlie Drake Land, appear to have sat back and left him to it.

He began by talking over the opening bars by way of an introduction: 'Hello, there, my darlings! I shall now sing you my first golden disc'. This was followed by a growly, Sid James-style interruption - 'No chance!' and Drake's cheerily high-pitched reply, 'You never know!'

He then launched into the lyrics themselves, adding the odd ad-libbed aside every now and then but generally sticking to what had been written. It was his singing, however, that was destined to divide opinion.

He started: '...A-hoo the hunn-aaay co-ones...Wha-hy the hippooooh da-rones...Whaar the watt-tter foils...Whaaan the basket baaalls...'

It sounded as though he was supplying a sampler of several different approaches, all jumbled up in the same take. At one point he would be singing fairly comfortably within his 'normal' range; the next he would suddenly screech up to a glass-shattering shriek, or swoop down to a melodramatic stage whisper; or try a bit of choral warbling, cod-operatic vibrato, pub-style singalong or cartoon-like caterwauling. It sounded as though some kind of musical civil war had broken out inside Charlie Drake Land.

He then closed the song by talking in-between all the 'You never knows' (sung by Gabriel and Denny, pictured) until the fade-out: 'Well, that's it: my first gold...I wonder where Elton John buys his glasses...I shall have a swimming pool made in the shape of Shirley Temple...I suppose I'll have tax troubles...Might have to leave the Old Country...I hear the East India Dock Road is safe...Ah-dom-ah-dom-dom-ah-dom-dom-dom..'

It was, in every sense of the word, an extraordinary performance. Was he so unimpressed by the song that he decided to treat it with the contempt that it deserved? Was he so excited by it that he tried too hard to do it justice? The completed recording invites (at the very least) either interpretation.

Drake himself would never (as far as we know) offer an explanation. There does not appear to have been any promotional interviews about the project (even though, as he was desperate to keep his name in circulation during his enforced absence from the stage and screen, he was talking regularly to friends in the press), and the relevant chapter in his autobiography (published in 1986) omits any mention of the song or the occasion.

As for the reaction of Peter Gabriel, along with Martin Hall and Steve Nye (who co-produced the track under the collective pseudonym 'Gabriel Ear Wax'), that, too, remains, so far, unknown. Once their job was done they simply departed.

A completely unrelated composition was added for the B-side. It was called I'm Big Enough For Me - the theme song from a recently-released children's sci-fi comedy called Professor Popper's Problem (featuring Drake as a science teacher whose shrinking formula causes chaos in his classroom). Written and produced by Ray Glastonbury, it was sung - in jarring contrast to the A-side - entirely 'straight' by Drake.

The single was then handed over to Gabriel's record company Charisma, where it met with, to put it politely, a less than enthusiastic reception. The label's General Manager, Gail Colson, would later tell the music journalist Daryl Easlea that her sole memory of the disc was of it 'being delivered and then trying to work out how to sell the bloody thing!' Oddly enough, her brother Glen Colson, who was the Press Director at the time, would later protest that he 'never heard about it', had not been involved with it, and that the story of the entire episode struck him as 'a bit far-fetched', but certainly someone in his office eventually came up with the following information for the tabloids and music weeklies:

The single is produced by Peter Gabriel. Erstwhile lead singer with Genesis, and sometime human sunflower. It is a send-up of pop stardom which also features Sandy Denny, Eno and Robert Fripp. As Drake is chalk to Gabriel's cheese, so is the idea of Charlie encountering a groupie - listen to the single and you'll discover what happened.

The puff pulled the wool over no one's eyes. Released on 21st November 1975, the single sank like a stone.

Ignored by the critics, avoided by radio and shunned by fans of music and comedy alike ('The record did nothing,' Laurie Mansfield confirmed to me. 'Less than zilch!'), it was a miss that went straight into myth.

According to Mansfield's recollection, there might actually have been plans for the comic and the rock star to work together again - 'I seem to recall,' he told me, 'that [the song] was part of a larger project that Peter Gabriel was working on' - but, if so, such a project swiftly swirled along with the single straight down the drain, and the improbable Gabriel-Drake partnership, in turn, duly disappeared into its own 'That's All Folks!' Looney Tunes-style abyss.

Gabriel soon ended his self-imposed sojourn in semi-ordinary life and started a solo career, recording new songs in studios in England and America. His critically-acclaimed debut album, Peter Gabriel, would be released in February 1977. Among its tracks was another (but better) collaboration with Martin Hall, the barbershop-style Excuse Me, and his first hit single, the semi-autobiographical Solsbury Hill. He was back in the music business, but this time on his terms, and his future, as an international star, was bright.

Charlie Drake, meanwhile, was left a while longer in limbo. The tireless Laurie Mansfield was still leaning on Equity to relent, but it was a slow and delicate process. In September 1975 the Daily Mail launched a campaign to get Drake 'reinstated in show business,' and the following month it was reported that Equity's then-General Secretary, Peter Plouviez, had met informally with Drake for discussions that, although proving inconclusive, were described as having been 'pleasant and constructive'.

Ironically, while a deeply frustrated Drake had to sit out what would normally have been a busy and lucrative Christmas period, he would have noticed in the trade papers that Sue Moodie, whose presence in his last panto had sparked the whole saga, was back on the stage as a full-time performer. She was now a paid-up member of Equity.

Drake himself would have to wait until early in 1976 for his own career to resume. On 19th January, Equity's associate organisation, the Provincial Theatre Council, having tired of all the negative publicity, ruled that the comedian would not have to pay his long-standing fine after all, but would instead have to complete a ban that was now set to end on 1st March.

Drake hailed the verdict as an historic personal triumph - 'This is a victory for the little man,' he proudly told the press - but his prolonged absence from work had cost him an estimated £60,000 in lost earnings (around half a million by today's value) and plunged him, as he put it himself, 'hopelessly' in debt. The result was that he had to grab at just about any job offer going, starting with a role on TV supporting the middle-of-the-road music duo Peters and Lee (an engagement which this most accident-prone of comics marked by misjudging a stunt involving a model made of live matches and singeing his own eyebrows).

He would always insist, however, that he had no regrets. 'I'm still Charlie Drake,' he said with a defiant smile, and, a couple of years later, he was back - and sounding far more at home - with yet another novelty single, Super Punk ('I hate ya an' I wanna be baaaanned!').

As for You Never Know, it now seems doomed to be one of the songs that nearly all of those involved either actively expunged from their mind or else stubbornly refused to admit that they still remembered. One can surely sympathise with such an attitude.

The song is what Peter Gabriel and Charlie Drake got up to on their holiday, and it is probably for the best, in this case, that what happened on holiday stayed on holiday.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreCharlie Drake - Drake's Progress: An Autobiography

For twenty-five years Charlie Drake was at the top of the UK show business ladder (films, TV, stage productions, 15 Royal Command performances, etc), but it all crashed after a row with Equity, and his career was in ruins. There followed the slow climb back, eventually to a new level of success outside his familiar world of variety.

First published: Wednesday 1st October 1986

- Publisher: Robson Books

- Pages: 224

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Robson Books

- Catalogue: 9780860513704

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.