The Duce of Entertainment: Comedy, commercial TV and Val Parnell

Following on from the profile of Jack Hylton, here is the second article in this occasional series within Comedy Chronicles in which Graham McCann looks at the main impresarios involved in comedy over the past century.

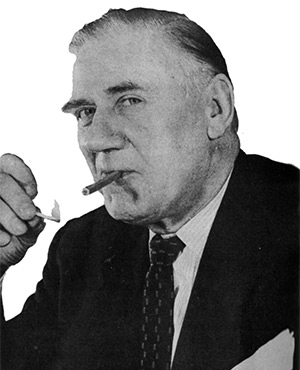

The term 'impresario' is related semantically to the Italian phrase for undertaker, and there has always been something unnerving and intimidating about the biggest of these beasts, because they have the power not only to boost you but also to bury you. Val Parnell certainly acquired, over time, that kind of an aura, and he was never afraid to exploit it.

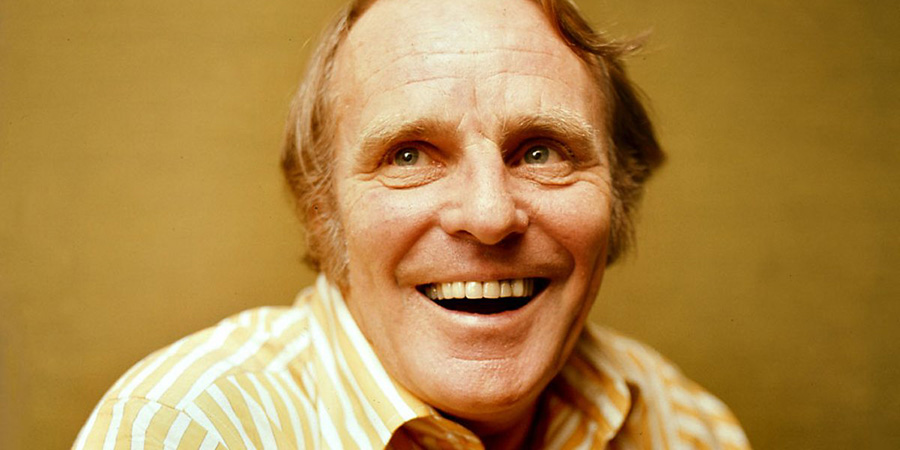

Parnell was one of Britain's most significant and influential impresarios of the twentieth century. A major manager of the live variety circuit, a powerful promoter of talent and one of the pioneers of commercial television, he helped shape, maintain and move on what passed as popular entertainment in this country for the best part of fifty years.

Born Valentine Charles Parnell in 1892 in London, he was the son of Thomas Parnell, who, under the stage name of 'Fred Russell', was the most influential ventriloquist of his day and one of the founding figures associated with the Variety Artistes' Federation. Val's own career in show business began at the early age of thirteen, when he started work as an office boy on the variety circuit.

Over the next few years he would learn the ropes and pick up all the tricks. He would come to know everything about his profession from the box office to the boardroom.

By the 1920s he was working for the General Theatre Corporation (GTC), which ran a thriving chain of theatres, dance halls and cinemas, as a talent spotter and bookings manager. When George Black - a crafty, canny, showman who had started out promoting a flea circus - took over the running of the company in 1928, Parnell became his protégé.

Black, with Parnell studying his every move, managed more and more theatres, including the prestigious London Palladium, as well as many other prime venues all over the country, and also took control over the production of the annual Royal Variety Performance. He oversaw the merging of GTC with the Moss Empires variety circuit in 1932 - thus establishing himself as the most powerful impresario in the business at that time - and in 1937 he signed up the Crazy Gang comedy troupe, who under his guidance and patronage would go on to be one of the most popular acts of the era.

Black gradually delegated more and more responsibilities to the eager and industrious Parnell, whose own profile, as a result, grew increasingly prominent in the world of show business. Built like a heavyweight boxer, with an imposing personality to match ('I never smile', he'd growl at photographers. 'What have I got to smile about?'), Parnell struck performers and press reporters alike as someone they wanted to know but were somewhat afraid to upset.

He knew it, too. When visiting Black's productions, he would stand in the shadows at the back of the empty theatre during rehearsals, just allowing enough light to fall on him to alert everyone that he was in the building, and simply stand there, arms folded and face blank, as a brooding presence, quietly enjoying the nervousness that was rippling throughout the cast and crew.

There was far more to him, however, than image. He knew who was good, who had potential and who was stealing a living. If he found you underwhelming, you were treated as if you barely existed, but if he liked you, he could lavish you with care and attention.

The Crazy Gang, for example, had originally been known as George Black's troupe, but Parnell, having first booked them on his boss's behalf, became increasingly close to them as the years went on. He would fuss over their contracts, pore over every detail of their productions, play a hands-on role in organising their publicity and generally doing whatever he could to make them feel wanted and well-managed.

In most cases, however, he preferred to keep a degree of distance between himself and the talent, so that he, but not them, felt free to step forward or step back, depending on what warmth or coldness was needed in any particular circumstance. No matter how big the star got, Parnell never let them forget that they were not as big as their boss.

He became the official head of the Moss Empires circuit in 1945, at the age of 53, after the death of George Black. This, then, marked the beginning of Parnell's period as an impresario in his own right, and he seized the opportunity to stamp his signature on the post-war era of entertainment.

One of his most noticeable trademarks - admired by some, and quietly resented by others - would be his policy of bringing over big American stars to top the bills in many of his British shows. This had, to be fair, been George Black's preference too, and, while booking for Black before the war, Parnell had imported major music acts such as Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway and Josephine Baker to excellent effect at the box office.

Now that he was in charge, however, the practice became even more pronounced. All of the most important theatres he controlled would be visited by the likes of Bob Hope, Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye or Judy Garland. Some of the British stars, as a consequence, felt under-appreciated as well as under-employed, but the paying British public seemed to love it.

Parnell would often terrify those reporters who had the temerity to question his commitment to home-grown talent - the Parnell 'hairdryer' treatment was plugged-in and blasting long before it reached any Premier League football changing-rooms ('My job is to fill the theatre', he'd bark. 'If I feel British artists can do it, they will get the chance') - but the truth was that, as much as he did appreciate the best of the British stars, he was definitely dazzled by American glamour, and always wanted it as the glitter to garnish his London productions.

It continued to work, and Parnell oversaw some lucrative theatrical success stories throughout the remainder of the Forties and into the Fifties. Then, in the middle of the 1950s, came the prospect of commercial television, and Val Parnell was one of those show business figures who was drawn in by the thought of its potential.

Another impresario who moved in the same direction was Jack Hylton. The pair of them would thus share many of the same opportunities, challenges and concerns over the next few years, while responding to them rather differently.

Jack Hylton was Val Parnell's exact contemporary (they were born just a few months apart during the same year), as well as his occasional colleague and regular rival. Both men had climbed their way up the show business ladder, both had an eye for ability and a gift for grooming it, both loved to make a cultural impact with something big, bold and spectacular, and both of them broadly agreed that, as Hylton once put it, one should 'keep trying to please both a Woolworth audience and a Fortnum & Mason audience', whilst remembering that 'most people shop on the Woolworth level'.

There was, however, one key difference between them as media businessmen. Whereas Hylton could sometimes be a romantic, Parnell was ruthlessly realistic.

When Hylton went into television, therefore, as the man responsible for Associated-Rediffusion's entertainment output, he remained rooted in the theatre, and never really shook off the backward-looking belief that television was not that much more than a new means of promoting the old medium. Parnell, on the other hand, went into television, as managing-director of Associated Television (ATV), with the cold-eyed conviction that it was destined to eclipse the old medium.

While Hylton thus clung on to his theatrical empire, Parnell started to shed his. In his head, and perhaps even his heart, he had already moved on, with his eyes set on a different prize.

Being a pragmatist, he still made full use of his theatrical connections, and investments, as he settled into television. Indeed, his flagship show as a programme-maker would be Val Parnell's Sunday Night At The London Palladium (1955-65) - a variety series that was very similar to the kind of format that Jack Hylton was now putting out, with the notable difference that it was slicker, more stylish and better directed for a television audience.

Hylton seemed to lose his nerve very quickly and concentrated on catering to a 'Woolworth audience'. Parnell held his and tried to accommodate, at least to a degree, a 'Fortnum & Mason's audience' too (although when, for example, the BBC broadcast a production of La bohème, he didn't hesitate to stick on yet another variety show to woo over the Woolworth crowd).

Val Parnell's Sunday Night At The London Palladium proved to be one of the bona fide successes of the early days of the ITV network. It was big, it was glamorous, it was fast-paced, it had comedy, music, games and surprises - there seemed to be something for everyone, and everyone seemed to watch. It shot into the charts for the most-seen shows of the week, and it stayed there for years.

Having conquered one day of the weekend with this kind of grand and glossy entertainment extravaganza, he then went ahead and did the much same with the other. Val Parnell's Spectacular (1956-61), which tended to focus more on one particular star, swiftly became a fixture in the schedules every Saturday (sometimes shrinking the BBC's share of the available audience to well under ten per cent). Hylton was having his own, more modest, success with similar shows over on Associated-Rediffusion, but in most other ways he was being out-thought and out-performed by his old rival.

In contrast to Hylton, Parnell was shrewd enough to realise that, while this traditional variety format was a sensible starting-point for his time in television, he needed his team to come up with a diverse range of programmes that seemed, in a meaningful and visually-recognisable way, expressly 'made for television'. While Hylton seemed to get stuck, therefore, in trying to bring the old variety theatre to TV, Parnell pushed on with the task of making TV really seem like TV.

There were panel games and quiz shows. Such US imports as The $64,000 Question (1956-8) and Tell The Truth (1957-61) proved especially popular and led to innumerable home-grown variations.

There was drama. The Play Of The Week (1955-66), while not originating exclusively at ATV, became a major outlet for some of its one-off dramatic productions, while Parnell made good use of his connections with H. M. Tennent and their theatrical library of crowd-pleasing scripts, and also encouraged the planning of numerous in-house projects.

There were soaps. Parnell and his colleagues, having studied trends on US television, knew exactly what they wanted for ATV in this area, and Emergency Ward 10 (1957-67), followed by Crossroads (1964-88), became staples of the schedules.

There were talent shows. Carroll Levis Discoveries (1957), for example, had a short but influential run on the channel, and other, similar, programmes followed.

They were daytime magazine-style leisure and chat shows. Parnell starred one of his secret on-off lovers, Noele Gordon, in most of them (Lunch Box, About Homes And Gardens and Teatime With Gordon), although the journalist Clifford Davis was also given a US-style series for Saturday evenings called Show Talk (1956).

There were current affairs programmes, debates and 'serious' talk shows. Academics such as the historian A.J.P. Taylor were sometimes given short slots to give mini-lectures, while series such as Paper Talk (1956-9) allowed journalists to argue with public figures about the controversial issues of the day.

There were music shows - featuring not just jazz, cabaret and Hylton-style big band music, but also, increasingly, chart-based skiffle, rock and pop acts. The Jack Jackson Show (1955-9), Top Tune Time (1958), Disc Break (1959) and The Tin Pan Alley Show (1960) were just a few of the many formats that were explored. Parnell's own Sunday Night At The London Palladium would also serve as a showcase for changing trends and talents, featuring the likes of Cliff Richard and the Shadows, and later The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, on their famously varied bills.

There were sitcoms. The Larkins (1958-64), which co-starred David Kossoff and Peggy Mount, was a family-oriented concoction which set the style for the channel for some time.

There were also plenty of sketch shows (which, in contrast to Jack Hylton's often lazy 'filmed at the theatre' productions, were usually planned, staged and recorded in 'proper' television studios). The early range encompassed multiple performers in Young And Foolish (1956) along with such star vehicles as The Harry Secombe Show (1955), The Benny Hill Show (1957), The Howerd Crowd (1957), Cooper's Capers (1958) and The Arthur Haynes Show (1957-66).

It is important to note that many of these projects were not initiated by Parnell himself - again unlike Hylton, he benefitted from a much bigger and broader team of creative people beneath him, and had far greater commissioning powers - but he did, to varying degrees, lend his support to them, and used them, as MD, to develop ATV into an attractive and successful television channel (and did so with such an obsessively expansionist spirit that he used to drive around the streets counting how many new ITV aerials were sprouting on the roofs).

The critics hated Hylton's output with such a passion that they sometimes exaggerated its awfulness for rhetorical effect, while Parnell's productions benefitted occasionally far too much from the comparison, but it is fair enough to appreciate the breadth, if not so much the depth, of his own TV achievements. His ATV became a reasonably reliable source of mainstream, middle of the road, all-round entertainment, providing commercial TV with a centre that would hold, and serve as a reference point for rebellion.

In terms of British comedy, Parnell was effective without ever threatening to appear evangelical. He looked after that aspect of entertainment with the same professionalism that he afforded the others.

Although he often tried to hide it, Parnell did have a sense of humour ('I'm sorry', he once said to a comic auditioning for a West End show, 'but I don't want any profanity at the Palladium'. 'But I don't use any swear words', the comic protested. 'I know', said Parnell. 'But the audience would'). Having spent years booking comic talent for George Black, he knew all of the mechanisms, and magic, that made the funniest fly.

While in charge at ATV, he did much to find and fashion the form, as well as the content, of a great deal of what would pass as mainstream television comedy for the following couple of decades. He did not, surprisingly enough, unearth that many fresh young comic talents during his time in TV - aside from the all-round abilities of Bruce Forsyth, his channel's major 'discovery' in this sense was the forty-two-year-old Arthur Haynes, while Morecambe & Wise arrived via an earlier spell at the BBC - but he did keep booking the best stars available, intervened to improve ATV's access to the most promising up-and-coming writers, and - in stark contrast to, say, Associated-Rediffusion's unimaginative reliance on old-fashioned variety shows - worked imaginatively and assiduously to ensure that the full spectrum of styles and genres started being explored and exploited.

It was ATV, for example, that was quick to start developing sitcoms and sketch shows as well as theatrical productions. It was also ATV that had the courage (at least initially) to produce something as admirably inventive and unconventional as The Strange World Of Gurney Slade (1960). Whereas Jack Hylton, for example, seemed to struggle to shift his attention from what had been popular in the past, Parnell made an effort to seek out the seeds of future pleasures.

One aspect of the impresario's art where Parnell was distinctly inferior to Hylton, however, was man-management. An impatient character at the best of times, he had little tolerance of 'artist problems', expecting them simply to be grateful for what each job paid, and, believing none of them to be irreplaceable, would much rather dispense with them than debate with them.

Hylton was a tough enough businessman to make enemies if it seemed necessary, but it was never something he welcomed. Parnell, in contrast, seemed to regard such things as simply the price of power ('Mr Parnell', called an anxious secretary after a drunken, and recently-sacked, performer had staggered into the building, 'there's a man downstairs who says he's going to shoot you!' Parnell simply muttered: 'Tell him to get in the queue').

Hylton, having spent years as a performer himself, knew that the management could sometimes make mistakes, and, through his years as a band leader, understood that artist morale was an important thing to maintain, and so he was often prepared to put an arm around a shoulder. Parnell, however, much preferred to put a hand around a throat.

His path towards becoming a powerful impresario was littered with the battered bodies of those who had dared to challenge him. One example was the case of Tommy Trinder.

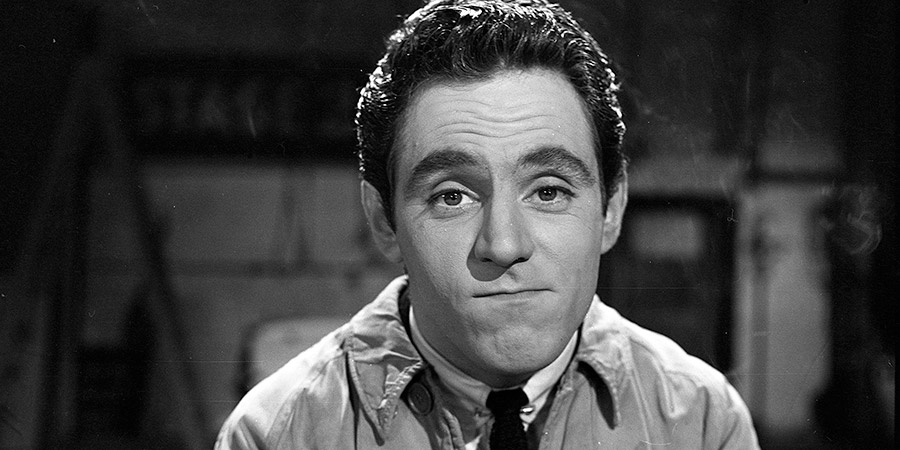

In the mid-1950s, as the original host of Parnell's Sunday Night At The London Palladium, Tommy Trinder seemed to have it all. Playing regularly to an estimated twelve million viewers, the programme had quickly cemented Trinder's status as one of the country's biggest comedy stars, as well as probably the wealthiest.

He had always been an irreverent comedian, quick to joke about anyone or anything that struck him as likely to spark a laugh, but now, as all the fame rushed to his head, he started - in the eyes of Val Parnell - to go too far. He would mock his own show if something went wrong; he would mock its sponsors if he disliked the products they were plugging; and, worst of all, he would sometimes mock his bosses if he thought they had made a mistake.

It was rarely ever done with any real malice. Trinder was just a gag machine, and a famously instinctive ad-libber, who said whatever came into his head if he felt it would keep the laughs coming. Parnell, however, was not laughing.

Feeling that he had created a monster, he soon started looking for a means of removing him. It could not happen immediately, simply because Trinder was still proving so popular, but the process began with Parnell instructing his producers to start searching discreetly for a suitable replacement.

A succession of up-and-coming talents were duly given guest spots and quietly assessed, until one of them - Bruce Forsyth, who not only looked rather like a younger, fresher, version of Trinder, but also had a similar, but less abrasive, comic style - impressed everyone behind the scenes. Parnell then felt the time was right, and brutally blocked Trinder not only from his own show, but also from anything else on ATV.

The comedian had not done anything truly outrageous. He was guilty merely of going slightly too far on the odd occasion, and of daring to sometimes disagree with his bosses. Other employers might have called him into their office, made a few things painfully clear, and then moved on with the professional relationship. With Parnell, however, there were rarely second chances, and, as Tommy Trinder found out to his cost, if he felt that you were finished, you were finished in the business, more or less, for good.

While Parnell went ahead and shaped the more pliable Forsyth into one of the biggest stars of the next decade and beyond, therefore, Trinder was suddenly reduced to touring the provinces and playing the clubs, as lonely as a former mob lieutenant dumped in the Las Vegas desert.

The same thing could easily have happened to Dickie Henderson. Early on in his television career, in 1956, ATV offered the well-regarded young entertainer a new TV series, co-starring with the Scottish comedian Chic Murray, called Young And Foolish. Billed as a 'song, fun and dance show', the show suffered so much, so quickly, from script problems and backstage personality clashes that a desperately unhappy Henderson, after struggling through the first episode, asked to be released from his contract 'on the grounds that the public should enjoy a little respect'. Parnell, appalled at what he saw as sabotage, blamed Dickie for the debacle and told him in no uncertain terms that he would not be welcome on any future ATV productions.

The only thing that saved the ostracised performer was the intervention of one of the boss's new favourites, the producer Brian Tesler. Considered one of the brightest prospects on the other side of the screen, Tesler had only just been poached from the BBC.

On his first day at ATV, he informed his new bosses that he wanted for his initial project to make a Saturday night show with Dickie Henderson as its star. Parnell, sure enough, moved to veto the proposal, but Tesler had a clause in his brand-new contract that allowed him the power to cast his own programmes.

The frustrated Parnell thus had no option but to allow the 'difficult' performer an unexpectedly swift return to ATV, but, still determined to register his displeasure, he insisted that the name of the show would have to be Val Parnell's Saturday Spectacular and not, as Tesler had intended, The Dickie Henderson Show. The opening edition, however, proved so popular, with Henderson's performance so impressive, that even Parnell, for once, felt obliged to back down. He sent Tesler a congratulatory telegram, which read: 'Terrific. It can now be called The Dickie Henderson Show'.

Parnell would go on to be so impressed by Henderson's versatile performing and hosting talents that he ended up being one of his strongest supporters. Henderson, nonetheless, never forgot that, if he suffered one more strike, he would be out - and this time for good.

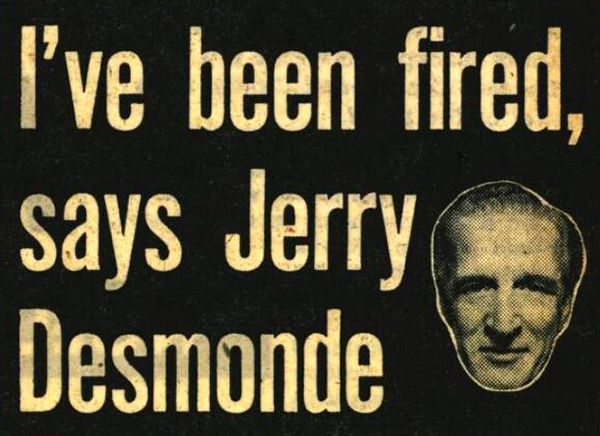

Then there was Jerry Desmonde, the great straight-man to the likes of Sid Field and Norman Wisdom, who for a time in the late-1950s was one of the most popular quiz show hosts of the era. Starting with a short stint on Hit The Limit early in 1956, and then moving on a few months later to become the star of the much bigger US import, The $64,000 Question, Desmonde, with his suave and calmly authoritative on-screen demeanour, was one of ATV's most trusted talents - until, that is, he upset Val Parnell.

Desmonde had never been considered a 'difficult' person, but he rarely hesitated before offering producers his opinions, and certainly felt, during his ATV years, that his input, as the star of his shows, should be welcomed. It seems, however, that it was not.

Parnell rated his quiz show hosts very low in the on-screen hierarchy. He did not think that anyone could do their job, he appreciated it was a position that required polish and poise, but he had no time at all for preening card-reading prima donnas, and if the slightest suspicion of 'trouble' brewing on those productions was brought to his attention he never hesitated to root out the problem. Desmonde was thus rudely rooted-out.

The two flimsy excuses given to the press by ATV were that his contract had simply expired (which, seeing as the common practice at the time was for separate contracts for separate series, was a blatant statement of the obvious) and, far more risibly, that some viewers had 'not liked the way he put on and took off his glasses' when reading out questions. Desmonde took such PR sophistry as tantamount to a provocation, and duly bit back.

If his behaviour prior to his departure had irritated Parnell, then his actions immediately afterwards certainly infuriated his erstwhile employer. Rather than do the 'decent' professional thing, as far as the boss was concerned, and creep quietly away to wait patiently for an issue of forgiveness, Desmonde rushed to the newspapers and ranted about all of his ATV bosses, accused them of treating him unfairly, and insisted that he had been handed 'a raw deal'. It was this show of defiance that probably did for Jerry Desmonde.

Suddenly, the star found himself thrust out into obscurity. There was still occasional film work being offered, but his TV career - at least as a prominent personality (there would, for a short while, still be the odd one-off and minor engagement) seemed to shut so quickly and definitively that, for the rest of his life, he would remain convinced that Parnell had privately blacklisted him.

'When one door closes', Desmonde complained bitterly, 'they all close'. Sometimes reduced to driving a mini-cab to top-up his finances, and depressed by his wife's declining health and eventual death, he committed suicide just under a decade after his disappearance from television.

The entertainment business, in those days, was an exceptionally ruthless business, and some of that ruthlessness came from the way that Parnell ruled. 'They bow to Royalty', one insider said. 'But they kneel to Val Parnell'.

Only the odd one managed, without any internal intervention, to survive incurring the displeasure of such a despot. The comedian Max Miller did so simply by waiting until his career was too copper-bottomed to be crushed.

The fifty-five-year-old Miller, when booked to appear in the 1950 Royal Variety Performance, was so incensed to have been limited, as one of Britain's biggest and long-established comic stars, to six minutes on stage while America's Jack Benny was afforded twenty, he went rogue, abandoned his script, and went on for twice as long as expected. Furious at the mess Miller had made of the schedule, and outraged at the insolence he had shown to his superiors, an apoplectic Val Parnell sought him out afterwards and shouted: 'You'll never work the Moss Empires again as long as you live!' Miller, however, simply shrugged his shoulders and retorted: 'Mr Parnell, you're thirty thousand pounds too late!'.

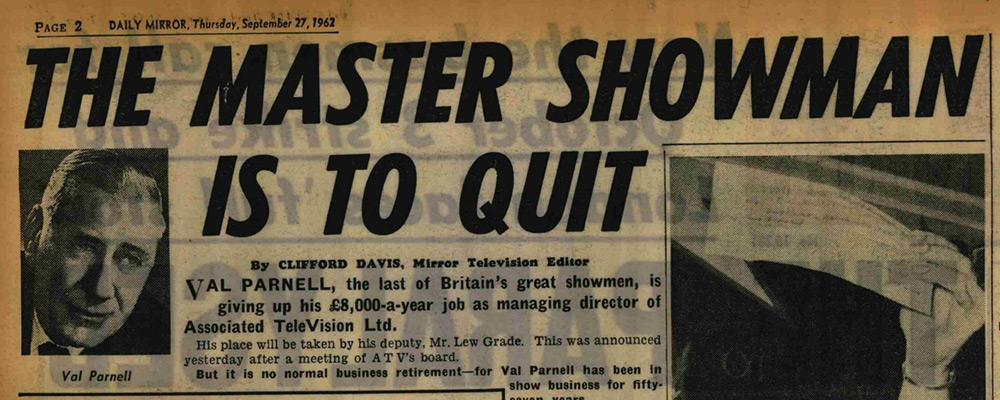

In an industry where it seemed a knife was almost as likely as a hand to land on one's back, Parnell's own professional demise arrived shortly into the Sixties, courtesy of his deputy, Lew Grade. Having recently lost a fierce and bitter power struggle with his fellow impresario Prince Littler (named, incidentally, after neither a patrician nor a pooch, but merely a family ancestor) concerning the control of Moss Empires, Parnell's position as managing director at ATV - where Littler happened to be chairman - was suddenly rendered fragile.

Parnell remained defiant, insisting that he was 'fireproof'. Lew Grade had other ideas.

Now a victim of his own abrasive behaviour, having made far more enemies than friends, the many people who had long resented his attitude now grouped together to speed his end. Grade, who was hugely ambitious in his own right, knew that Parnell had not only lost the support of most of the boardroom, but was also facing public embarrassment with the imminent exposure of some of his many affairs. The target was there for the taking.

One night in September 1962, therefore, Parnell was sitting down to dinner in his home with a couple of his associates when the phone rang. As one who was present would later recall: 'He left the room and took the call. When he came back after a very short while he was... well, I can only describe it as ashen. He sat down and just said to [his current lover] Aileen: "Lew's fired me"'.

Parnell announced his intention to go down fighting. A week later, however, on 26 September 1962, he reluctantly stepped down as MD, telling reporters he was doing so simply 'to give the younger ones a chance'.

Although he would stay on at the company and continue to lend his name to some of its variety programmes, Parnell finally resigned from the board of ATV in 1966 to live in retirement in France. He died a decade later, aged 80, on 22nd September 1972.

His legacy, as one of the country's most powerful and influential showmen, would continue to command great respect, if not quite so much affection. It is his ends, rather than his means, which still inspire.

See also:

Jack Hylton profile

Lew Grade profile

Bernard Delfont

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more