Up the polls!: Election campaigns and comedy

It's a great compliment, in a way, that British politicians think of comedy as a potential vote changer. Once election campaigns begin, those whose political opinions one might assume ought to have the greatest impact - you know, people who actually study the subject - are left to chatter away to their heart's content, while comedians are policed almost as hysterically as a group of harmless football fans in Paris.

It seems more than a little over the top. True, there has been some provocation - comedians have been poking fun at politicians since classical times, and George Orwell did once claim that 'every joke is a tiny revolution'. As Peter Cook observed, however, the soft-powered satire of 'those wonderful Berlin cabarets' still failed to halt the rise of Hitler and the outbreak of the Second World War. Somewhere along the way, politicians lost that proper sense of perspective.

It was probably television that did it. Radio, back in the day, certainly had the reach to rattle the inhabitants of Parliament, but thanks to the BBC's 'Green Book' - the post-war in-house policy guide for the makers of popular programmes - it was ruled that 'political issues should not be made the running theme of any light entertainment programme', and there was an explicit ban on 'anything which can reasonably be construed as derogatory to political institutions'.

When television began, however, it was handed no such sobering warnings from up on-high - partly because so few in politics appeared to take it that seriously. The first post-war PM, Clement Attlee, regarded the medium as 'an idiot's lantern', while the second, Winston Churchill, was convinced it was a minority enterprise 'honeycombed with Communists', so both did their best to keep political matters well out of the picture.

The only interest their immediate successors felt for the small screen was when they wished to impart some important information, such as when, in 1956, Sir Anthony Eden thought that he may as well mumble a few words about what was going on with the Suez crisis. Television treated these rare and isolated occasions much like a suburban family reacted to the vicar coming round for tea, and so comedy, in particular, was shut safely away inside a small dark room, like a naughty child, while the grown-ups concentrated on being dutifully deferential.

It was easier, however, to keep mainstream television from meddling with politics while politics still resisted the temptation to meddle with mainstream television. Once this began to change at the end of the 1950s (when Labour's election broadcasts, in search of a bigger and younger audience, deliberately mimicked the format of a TV magazine programme, and even featured 'humorous' cartoons) so, too, did the nature of the relationship between the medium and its masters.

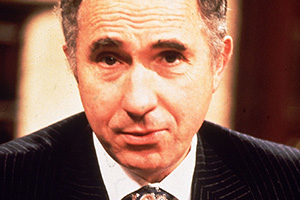

The dynamic definitely grew more complicated early into the following decade, when the more image-conscious Harold Wilson became leader of the Labour Party in 1963. Wilson, at that time, was one of the more progressive figures in Parliament when it came to his attitude to television. This is not to suggest that he was particularly positive about the medium in general, but it is to say that, more than most of his contemporaries, he recognised its potential power, and impact, on the culture and society of the time, and appreciated that, whether they wanted to or not, politicians had better master this medium or risk being mastered by it.

He thus invited the cameras into his home to film him doing such 'ordinary' activities as mending his son's bicycle on the living room carpet, drinking mugs of builder's brew in his kitchen and doing a spot of digging in the garden. Whenever there was an opportunity to use TV to his advantage, he invariably went ahead and did so.

The misfortune for Wilson was that his rise to the top of British politics coincided with the rise of television satire, so he was offering TV his cheek just when it was in the mood to slap it. That Was The Week That Was, for example, started ruffling so many political feathers that (just a couple of weeks after it started, towards the end of 1962) a furious Reg Bevins, the minister then-responsible for broadcasting, threatened 'to do something about it' following some light-hearted criticism of his colleagues. 'Never before,' claimed the Daily Mirror, 'has there been such a tizzy over a BBC TV comedy series.'

The boiling Bevins was made to simmer down eventually by his Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, who, rather wisely, preferred to project an air of aloofness rather than anger in such circumstances. Officials at Number 10 informed the press that 'Mr Macmillan has no television set [...], could not spare the time to watch television and, anyway, he just did not care about such matters'.

By October of the following year, however, far more politicians had come to feel just as bitter as Bevins, complaining about 'misquotations', 'adapted newsreels' and 'tampered sound tracks'. After TW3 suggested that the electorate would soon be facing a bleak choice between 'Dull Alec' (Macmillan's skeletal-looking successor, Alec Douglas-Home) and 'Smart Alec' (the tightly-coiled ball of self-admiration that was Harold Wilson), some of the more conservative members of Parliament (seemingly unaware of what the likes of the caricaturist James Gillray got up to in the Eighteenth Century) were raging at such 'unprecedented' irreverence. The following month, the BBC's Director-General, Hugh Carleton Greene, decided, with great reluctance, to cancel the series before the next election campaign commenced. Although all of the major political players hastened to issue statements assuring the millions who loved the show that they had played no part in its disappearance, they were rejoicing behind the scenes that all of the pressure had at last paid off.

The official explanation given for the show's demise was that it would have lost its 'bite in a General Election year because it could not comment on election issue', but, even if this had indeed been the real and only reason, it was merely reinforcing what was actually mainly a myth. There was nothing, for example, in any of the earlier or latest incarnations (1952) of the BBC's Charter (an extremely vague document at the best of times) or any other broadcasting acts (ditto) to prohibit (outside of formal current affairs coverage) the poking fun at politicians and their parties during election campaigns, right up to the day of the actual ballot, so long as the barbed remarks were reasonably fairly distributed, and the same was true for the new commercial networks. It was far more - then as now - the implied threat of post-election reprisals that encouraged broadcasters to impose their own unofficial period of 'purdah' on the proceedings.

The premature demise of TW3, however, did nothing to discourage the ongoing decline in deference in British culture and society, nor the rise in the reach of television. Buoyed by the arrival of a third channel, BBC Two, in April 1964, more than three quarters of the UK population now owned a set and were watching TV every evening as a matter of routine, with politicians looking on at the phenomenon with a mixture of curiosity, envy, anxiety and fear.

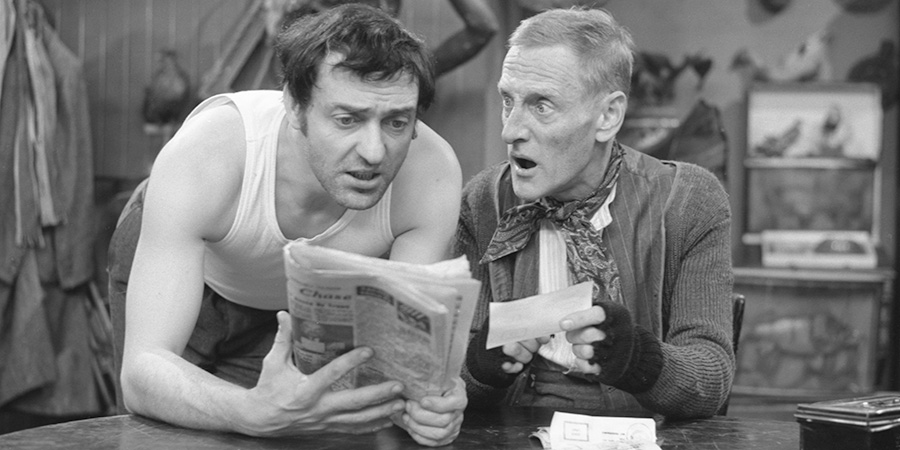

A sign of just how jumpy some MPs had become about the impact of the so-called 'box in the corner' would arrive during the General Election campaign in the autumn of that year, when the popularity of one programme in particular prompted panic to break out in the headquarters of the Labour Party. It was the sitcom called Steptoe And Son.

Steptoe And Son was, undeniably, a huge hit. Its first three series, it was reported, had attracted the biggest audiences for a BBC TV show so far recorded, with an estimated twenty-seven million viewers tuning in each week, and had recently been described by one newspaper as being 'as much a part of the national scene as The Beatles'.

The show was indeed now so big that Harold Wilson feared that, if an episode went out on election night, it might actually stop a significant number of people - especially, he believed, Labour-supporting people - from paying a visit to the polling station. He became convinced, therefore, that, in what was expected to be a close contest, stopping Steptoe And Son might just possibly save the day for Labour.

What is often overlooked about this peculiar incident, and this particular run of shows, was the fact that Wilson's concern was not even about new episodes: these were repeats. Steptoe And Son was such an important show that the Leader of Her Majesty's Opposition was genuinely scared that even an episode that about half the nation had already seen earlier in the year would prevent many of them from venturing out to vote.

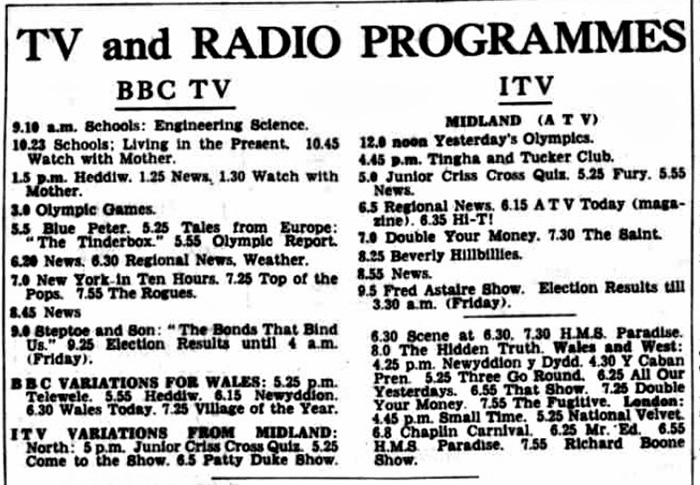

This fear, odd though it might now seem, was not entirely unjustified. The re-run of the third series had begun on BBC One on Thursday 24th September at 8pm, and again went straight into the list of the top ten most-watched shows of the week, with an audience this second time around of about fourteen-and-a-half million.

The episode due to go out on election night - The Bonds That Bind Us - did contain something of a mild political theme, with young Harold railing against the 'something for nothing' culture while old Albert goes on a manic spending spree with the money he has won from his premium bonds ('Lovely shop, Harrods, ain't it?'). The approach was far too ambiguous, however, to invite accusations of ideological bias, so there was no legitimate reason for the show to be shelved - but it still managed to cause a controversy.

Wilson was so preoccupied with the prospect of its imminent arrival on the nation's screens that, one evening during the campaign, as furtively as he could, he left his home in Hampstead Garden and drove the eleven miles or so across London to the private residence of Hugh Carleton Greene, in Addison Avenue, Holland Park, to convey his concerns in person. It was destined to be an awkward encounter.

The Director-General would later recall that the Labour leader was already very evidently in an agitated state when he first stepped forth into his hallway: 'Wilson that evening began by accusing the BBC of plotting against him. I told him that he must really know in his heart of hearts that that was untrue, and unless he withdrew that remark there was no point in our discussing anything. We could just have a drink and that could be that.'

'He did withdraw,' Greene recalled, 'and [then] we talked about the Steptoe And Son "problem".' Wilson thus proceeded to emphasise how important he felt it was that nothing was going to distract voters on election night before polling closed at 9pm, and claimed that, according to his and his campaign team's calculations, a show with as broad an appeal as Steptoe - even as a repeat - that was scheduled anywhere in the eight-to-nine o'clock slot could cost his party as many as 'a dozen or more' seats.

'Hugh didn't think much of this argument,' Wilson later admitted. 'He said: "What would you prefer to put on between eight o'clock and nine o'clock?" I said: "Greek drama - preferably in the original".'

Greene, it seems, assumed initially that such a suggestion was intended merely as a joke, but then saw from Wilson's fixed stare that, in essence, a serious request had been made. The Labour leader did not want anything too 'watchable' shown in that all-important hour.

'The next day,' Greene would recall, 'I discussed the matter further with the Controller of BBC One [Donald Baverstock] and we thought a good idea would be to shift it [Steptoe] from early in the evening until nine o'clock, when at that time the polls closed.'

This most independent-minded of D-Gs, however, was still uncomfortable about the idea of giving-in to political pressure, and felt honour bound to sound-out the show's producer, Duncan Wood, and its two writers, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, before making the decision official. None of them, it is fair to say, was impressed by the news of Wilson's clandestine intervention.

'It was ridiculous when you think about it, but in a way it was a very real backhanded compliment,' Alan Simpson would later reflect. 'Wilson's reckoning was that if Steptoe was on at its usual time, all the Labour voters wouldn't go out to vote: a cheeky generalisation, that - that only Labour voters watched it - and a very snobbish attitude.' Ray Galton agreed: 'My considered advice,' he told me, 'was for the BBC to tell Harold Wilson, very politely of course, to get stuffed!'

In the end, after further reflection, Greene - who was busy fighting all kinds of fires in those fraught days of broadcasting, and needed to choose which risks were most worth running - decided that it would be prudent, on this particular occasion, to go ahead and put the programme back by an hour. 'I rang up Harold Wilson and told him about this decision,' he recalled, 'and he said to me he was very grateful.'

As a sign of defiance, however, the BBC decided to fill the eight-to-nine o'clock slot not with a Greek drama but rather with another programme that was actually quite popular in its own right. It was the American-made crime caper series (starring David Niven, Charles Boyer and Gig Young) called The Rogues, which itself was averaging about 13.5m viewers each week.

The move was not in fact motivated purely out of deference to Wilson's wishes. It was also made because Greene and Baverstock reasoned that, as the BBC's election night coverage was now set to follow straight after the rescheduled Steptoe, their politics programme stood to inherit a sizeable proportion of the sitcom's loyal audience. The decision, therefore, was ultimately deemed to be mutually beneficial.

On the day itself - Thursday 15th October 1964 - the polling closed, therefore, just as Steptoe And Son started. Even in its later and unfamiliar slot, the repeated episode still attracted more than thirteen million viewers.

Many hours later, deep into the afternoon of the following day, the election result was finally known: Labour had, only just, made it first over the line. 'He won, I think, by four [seats],' Greene would say of Wilson, 'and I've sometimes wondered what effect my decision had on British political history!'

Wilson - who was soon paying more attention to television than even many of those around him felt was healthy - would actually be at it again two years later, shortly before the 1966 General Election, when he asked Greene to postpone another hugely popular show, The Man From U.N.C.L.E., until after polling was over. On this occasion, however, the request was rejected. 'Wilson thought he had money in the bank at the BBC,' Greene would later explain, 'but when he came to cash his cheque it bounced.'

Wilson was so angered about this (along with the Corporation's coverage of current affairs in general) that he resorted to a petty attempt at revenge. Once the election was won, he made a point of snubbing the BBC and gave his first post-victory interview to ITV instead. Still rattled by the rebuff, the following year he appointed Lord Hill, one of the BBC's biggest critics, as its new Chairman to act as a disciplinarian and cut the Corporation - and Greene - down to size.

TV comedy, however, would actually grow more mischievous, rather than less, when it came to elections once the decade came to a close. In 1970, Johnny Speight, who had already provoked plenty of political controversy with his relentlessly socially-aware sitcom Till Death Us Do Part, was encouraged to come up with an idea - following the dissolution of Parliament on 29th May - for a special adaptation of the show to mark the forthcoming General Election.

Bill Cotton, who had just become the BBC's new Head of Light Entertainment, would later explain to me the background to the project:

The General Election team, led by Dick Francis [Head of Special Projects], they'd taken over Studio 1 [at TV Centre] and they were getting - I mean, God, they had so many resources there and were busy setting up telephone lines all round the world and pictures from bloody Mars and all that - and they came and said, 'When the polls close at ten o'clock [it had been moved from nine to ten following the previous year's Representation of the People Act], we've got to go out for an hour before the first results start coming in and we won't be able to speak about the Election. We're not allowed to. So we'll have nothing much to say about anything during that block of time. What can we do till the first result comes? Can you - Light Entertainment - do a programme?' And so we came up with the idea of doing this programme called Up The Polls.

Commissioned by Cotton's friend and colleague, the Head of Comedy Michael Mills, and produced by the chronically mischievous Dennis Main Wilson, the plan was thus to have Johnny Speight write a twenty-five minute 'no holds barred' political script, which would be performed 'as live' on BBC One immediately after the polls closed. Set in a pub, it would feature not only Warren Mitchell in his usual guise of Alf Garnett, but also guest stars Eric Sykes and Spike Milligan as the characters they played in Speight's other, deeply controversial, sitcom about trades unions and race relations, Curry & Chips.

Billed in some newspapers, rather confusingly, under the banner of The Campaign's Over!, Up The Polls duly arrived on the screen, at 10:05pm, on the night of 18th June. The irony was that, on this occasion, the comic intervention would end up causing more controversy internally than it would externally.

Some criticisms did come in from various religious leaders - the Archdeacon of Birmingham, for example, professed to have been 'appalled' by the show's 'very bad taste', while the Vicar of Pensnett objected to the 'bad language' - but most politicians were far too distracted by the elation or deflation engendered by their own election results to register any reactions. The real rows were raging inside Television Centre.

Bill Cotton would recall:

The script was outrageous, you know, and Paul Fox [the then-Controller of BBC One] was no fool - he thought this was going to do wonderful business - so he was happy to go along with it. There was one catch to it, however, and that was that when they started rehearsing - and they were going to rehearse and record, rehearse and record, and then they would have it ready on time - it went wrong. We started at eight o'clock, on the night, to be ready in two hours. But when they started filming it, Warren couldn't do it. He could not stop laughing at Spike Milligan's reactions. It became horrific. We just couldn't get it in the can. And in the end Dennis Main Wilson had to go down to Lime Grove and cut it literally as it was going out. Really!

And as a consequence of which we were two minutes late or something, and then Dennis phoned up HQ, expecting to be congratulated, and Paul [Fox] said, 'You're a bloody disgrace' or something like that. And Dennis was absolutely mortified. I mean, you know, here he had managed, against all the odds, to salvage the thing and he'd got savaged for it.

So they told me and I went storming up to see Paul. And he and Dick Francis were there and he said to me, 'Don't talk to me about Light Entertainment!' And I said, 'Do you mean all you fucking grown men, with all this bloody equipment, can't fill two tiny minutes? You should be bloody ashamed of yourself!' And I turned round and walked out. And I walked into the outer room and David Attenborough was sitting there - he was Director of Programmes in those days - and he said to me, 'Hello William, my God you look angry!' I said, 'Bloody right I look angry - with the Controller of BBC One!' And David sort of fussed over me to calm me down.

But the next day Paul Fox's secretary said, 'The Controller of BBC One would like to know if the Head of Light Entertainment would like to have wine with him'. So I said, 'Tell him I'm not thirsty'. So she said, 'Oh come on, Bill, come up, because he's absolutely mortified. He's been upset all day'. And so eventually I went up, and he said, 'I've got to mend fences here'. So I said, 'Well, don't you ever phone a member of my staff with a complaint. You're not in charge of Light Entertainment producers. I am. And you tell me if you've got a bloody argument!' And it all got very, very out of hand - in retrospect it all seems childish, but we soon made it up. We started laughing and it was all gone.

And that was the end of our election night adventure.

The BBC in particular, and British television in general, would grow much more cautious about any connections between comedy and election campaigns in the years that followed. The most egregious example of this self-censoring attitude occurred early in 1979, when Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn's new political/bureaucratic satire, Yes Minister, was being planned.

The pilot episode had been filmed on Sunday 4th February 1979, and a shooting schedule was in place for the series. Then, thanks to 'political concerns', the show was shelved.

There should not have been a strong enough reason for the sitcom to be suspended purely because it had political content, because one of its writers, Tony Jay, had a distinguished record as a former member of the BBC's Current Affairs department, and knew exactly how to keep such an enterprise, as the political thinker Michael Oakeshott would have put it, 'afloat on an even keel'.

'I took charge of that side of the script writing,' Jay later confirmed, 'and so there was never a problem with BBC policy. It was rather like being a libel lawyer: a really valuable one can tell you what you can do and say. It was the same with BBC policy: the more familiar you were with it, the more things you knew were perfectly acceptable; so it enabled us to be less timid about what we said about politics and the political system.'

The BBC, however, buckled in the face of 'events, dear boy, events'. The Labour Government was beginning to crumble, the widespread industrial unrest was worsening by the week and there were increasingly urgent calls for a General Election. The Corporation, panicking about the need to be seen to avoid political controversy during the run-up to an election, feared that Yes Minister, amongst its other overtly 'political' programmes, might well end up reaching the screen right in the middle of what was promising to be an exceptionally fierce and fractious campaign - so it pulled the plug on the production.

The election went ahead eventually on 3rd May 1979, with Margaret Thatcher's Conservatives winning by a majority of forty-four seats. Filming of Yes Minister was then allowed to recommence the following December. The first series finally reached the screen on 25th February 1980 - just under a year late.

Bearing in mind that Yes Minister scrupulously avoided references to any actual political parties or personalities, what exactly did the delay 'save' the British electorate from? A comical but largely accurate account of how Whitehall and Westminster commonly interact? The suggestion that all public officials were to varying degrees flawed and fallible human beings? An acknowledgement that foreign affairs, the domestic economy and integrated planning are very complicated and important matters? A recognition that some people feel they have reasons to resist change and others feel they have reasons to pursue it? How would exposure to, and reflection on, any of that have affected the average person's decision as to how to vote, other than, just perhaps, to have improved it?

The only reason, it seems, that broadcasters, and their various regulators, remain so afraid of letting comedy run free during election campaigns is because, as Yes Minister's Sir Humphrey would no doubt have put it, 'You might create a dangerous precedent'. The only response this position deserves is the one that Jim Hacker gave to Sir Humphrey: 'You mean that if we do the right thing this time, we might have to do the right thing again next time?'

The message for politicians is surely that the commitment to responsible communication begins at home: so long as they are happy to dabble in the dark arts of dissimulation, they are in no position to expect, let alone demand, that anyone else obsesses over 'due impartiality' in the coverage of such claptrap. The era of straight and mutually respectful election campaigns, if it ever existed at all (and the historical evidence strongly suggests otherwise), has certainly long been over, and so should the tradition of television's meek submission to a such an intensely manipulative process.

If politicians really fear that the electorate are so vulnerable to comedy, then they really need to take far more seriously the obligation to give them the kind and quality of education that will arm them against it. Jokes should be part and parcel of any and every election campaign, and if you don't want to be the butt of them, then don't try to ban them: just make more of an effort to avoid doing anything to deserve them.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreA Very Courageous Decision: The Inside Story Of Yes Minister

The behind-the-scenes story of one of the most successful and admired sitcoms of the 1980s.

In 1977 the BBC commissioned a new satirical sitcom set in Whitehall. Production of its first series was stalled, however, by the death throes of Jim Callaghan's Labour government and the 'Winter of Discontent'; Auntie being unwilling to broadcast such an overtly political comedy until after the general election of 1979.

That Yes Minister should have been delayed by the very events that helped bring Margaret Thatcher to power is, perhaps, fitting. Over three series from 1980 - and two more as Yes, Prime Minister until 1988 - the show mercilessly lampooned the vanity, self-interest and incompetence of our so-called public servants, making its hapless minister Jim Hacker and his scheming Permanent Secretary Sir Humphrey two of the most memorable characters British comedy has ever produced. The new prime minister professed it her favourite television programme - a 'textbook' on the State in inaction - and millions of British viewers agreed.

In the years since, Yes Minister has become a national treasure: Sir Humphrey's slippery circumlocutions have entered the lexicon, regularly quoted by political commentators, and the series' cynical vision of government seems as credible now as it did thirty years ago.

Much of this success can be credited to its writers, Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn, who drew on their contacts in Westminster to rework genuine political folly as situation comedy. Storylines that seemed absurd to the public were often rooted in actual events - so much so that they occasionally attracted the scrutiny of Whitehall mandarins.

In A Very Courageous Decision, acclaimed entertainment historian Graham McCann goes in search of the real political fiascos that inspired Yes Minister. Drawing on fresh interviews with cast, crew, politicians and admirers, he reveals how a subversive satire captured the mood of its time to become one of the most cherished sitcoms of Thatcher's Britain.

First published: Thursday 16th October 2014

- Publisher: Aurum Press

- Download: 10.53mb

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Aurum Press

- Pages: 320

- Catalogue: 9781781311899

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Spike & Co.

This is the story of how four people, grouped together inside a set of offices five floors above a greengrocer's shop on Shepherd's Bush Green in West London, launched a golden age of British comedy.

On any weekday morning, if you dared to clamber over the crates of fruit and veg outside on the pavement, and climb the five flights of stairs to Associated London Scripts, you would find Spike Milligan, Eric Sykes, Ray Galton & Alan Simpson, shaping the latest shows, swapping the odd story and searching for a funnier line.

Together, this eclectic bunch, and their bizarre office block, were responsible for a golden age in British comedy, which included The Goons, Hancock's Half Hour, Sykes, Steptoe And Son, Comedy Playhouse, The Frankie Howerd Show, Beyond Our Ken, Round The Horne, The Arthur Haynes Show, The Army Game, Bootsie & Snudge, That Was The Week That Was, and Till Death Us Do Part.

Spike & Co. is their incredible story.

First released: Thursday 19th October 2006

- Published: Wednesday 25th October 2006

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Minutes: 137

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 448

- Catalogue: 9780340898086

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 9th August 2007

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 448

- Catalogue: 9780340898109

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Thursday 5th October 2006

- Distributor: Hodder & Stoughton

- Discs: 2

- Catalogue: 9781844563111

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Complete Yes Minister & Yes Prime Minister

This complete collection includes every episode of the hugely popular political satire Yes Minister Series 1 - 3 (which first aired in 1980 on BBC 2), along with each episode in the subsequent two series of Yes, Prime Minister (which aired from 1986).

Meet the bewildered Rt Hon James Hacker, his scheming and equivocating Permanent Secretary, Sir Humphrey Appleby and of course, Bernard, the piggy-in-the middle, on their fraught journey through the corridors of power.

Easily the sharpest political comedy ever written, with clandestine help from real civil servants, and satire that bites so close to home it sometimes seems more like a documentary. This does the impossible: it makes politics not just fun but hilariously funny.

First released: Saturday 14th October 2006

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 7

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: BBCDVD2113

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: All

- Discs: 7

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: BBCDVD2113

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Till Death Us Do Part

Highly popular - and more than a little controversial - Johnny Speight's classic sitcom satirised the less acceptable aspects of conservative working-class culture and the yawning generation gap, creating a sea change in television comedy that influenced just about every sitcom that followed. As relevant today as when first transmitted, Speight's liberal attitude to comedy shone a light on some of the more unsavoury aspects of the national character to great effect.

Starring Warren Mitchell as highly opinionated, true-blue bigot Alf Garnett, Till Death Us Do Part sees him mouthing off on race, immigration, party politics and any other issues that take his fancy. His rantings meet fierce opposition in the form of his left-wing, Liverpudlian layabout son-in-law Mike, while liberal daughter Rita despairs and long-suffering wife Else occasionally wields a sharp put-down of her own.

Though all colour episodes exist, many early black and white episodes were wiped decades ago. The recent recovery of the episode Intolerance, alongside off-air audio recordings, allow this box set to include a complete run of the series from beginning to end.

First released: Monday 12th December 2016

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 8

- Minutes: 1,166

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: 7954597

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Complete Steptoe & Son

The classic 1960s British comedy series about a middle aged man and his elderly father who run an unsuccessful 'rag and bone' business. Harold (the son) wants to better himself but his father always seems to ruin things, sometimes accidentally and other times deliberately.

First released: Monday 29th October 2007

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 13

- Catalogue: BBCDVD2255

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Monday 31st October 2011

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 13

- Catalogue: BBCDVD3570

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.