Recalling Dora: The comedy triumphs of Dora Bryan

Why isn't Dora Bryan better appreciated these days? Is it because she once recorded a novelty single (All I Want For Christmas Is A Beatle)? Is it because in later years she talked at length about her religious beliefs? Is it because, to some modern media eyes, she is not middle class enough? Is it because not enough of her most repeated performances seem 'cool' enough? If so, none of that should matter, because, for her sheer talent and what she achieved with it, she deserves to be celebrated and respected as one of British comedy's pioneering women.

The breadth and depth of the praise that she received during her long career - for work that encompassed the theatre, radio, television and movies - was, by any standards, quite exceptional. She could play a wide range of characters; she could speak in practically any regional dialect; she could deliver subtle and sophisticated dialogue or broad and bawdy material; she could sing and dance and shine in musicals; and she was also, unlike most of her contemporaries as well as her successors, outstandingly adept at the technique of physical comedy.

Born in the village of Parbold, near Wigan in Lancashire, in 1923 (she would later claim, rather confusingly, that she had been 'born in Southport, but I really come from Oldham'), she started her performing career at the age of twelve, joined Oldham repertory theatre soon after leaving school, and toured with the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) during the war.

She was given her first big break, in the mid-1940s, by Noël Coward. It is often claimed incorrectly that he was the one who persuaded her to change her surname from Broadbent to the 'more theatrical-sounding' Bryan - the truth is that she had made the change herself several years before meeting him, taking the name from a box of Bryant & May matches (which was promptly misprinted in a programme without the 't') - but Coward certainly adored her. Casting her in productions of two of his plays in quick succession, Peace In Our Time and Private Lives, he would later say that there were few if any women who were as naturally funny as her, nor as warm and engaging as a performer.

She was also remarkably versatile. Over the next few years she played a spoilt and cynical fiancée in Robert Donat's movie The Cure For Love (1949); a warm and sympathetic streetwalker in Carol Reed's The Fallen Idol (1948); a gossipy neighbour in No Trace (1950); an unnervingly sybaritic former actor-turned-barmaid-turned-swinger in Emlyn Williams's stage play Accolade (1950); a tough and testy prostitute in Basil Dearden's The Blue Lamp (1951); a no-nonsense, smoking and sipping, heavy-lidded studio publicity agent in Lady Godiva Rides Again (1951); a cheerfully irresponsible single mother in Women Of Twilight (1952); multiple characters, classes, accents and attitudes in The Globe Revue (also 1952); and a kleptomaniac mermaid in Mad About Men (1954).

The critics, even in those early days, could not have been more positive in their appraisals: 'Here is a real comedienne'; 'A remarkable young dramatic talent'; 'She effortlessly carries the whole show on her shoulders'; 'As always, Dora Bryan steals her comedy scenes with alarming ease'; 'She is a compact genius'; 'In films she is invariably the character actress you remember instead of the stars'; 'A comedienne of wit and vitality with a happy ear for an accent'; 'She has an amazing gift for character studies'; 'Whatever she does is funny'; 'probably the wittiest revue artist of our time'; 'She's the greatest stage personality produced by Lancashire since Gracie Fields'; 'The brightest home-produced star to shine since the war'; 'Dora Bryan does everything beautifully'.

A male performer who garnered such garlands would have quickly been elevated to starring roles in movies, but Bryan, frustratingly, continued to be used - at least as far as comedies were concerned - to enhance under-written supporting parts rather than be let loose on the leading roles. In 1956, for example, she appeared opposite Terry-Thomas in The Green Man, with T-T playing Charles Boughtflower, a philandering bounder with the emotional age of about fourteen, while Bryan played Lily, the hotel receptionist with whom he enjoys the occasional tryst, while in 1958 she had a supporting role in Carry On Sergeant as a sweet-natured NAAFI worker called Norah, who dotes on Kenneth Connor's hopelessly fragile soldier Horace Strong.

She did what was expected, better than had been expected, and invested these characters with enough charm, distinctiveness and depth to make them believable and very watchable, but, as many critics agreed, it was a waste of her widely-celebrated comic abilities. It was left, rather ironically, to the makers of dramatic movies to provide her with the kind of opportunities that she deserved.

The kitchen sink drama A Taste Of Honey (1961), in particular, served as a showcase for her prodigious acting skills. Playing a vulgar, alcoholic and man-hungry working-class single mother ('Every wrinkle tells a dirty story'), she was utterly free of vanity as she explored the entirety of this complicated character's soul, at turns touching, funny, vulnerable, depressing, alarming, embarrassing, heart-breaking and heartless, but always human. It was a brilliant performance, and, thoroughly deservedly, it won her a Best Actress BAFTA.

It was television that was far quicker to properly respect her comic talent. Producers and writers, by the mid-1950s, were competing with each other to find her a suitable format, convinced that she was the closest Britain had, in comedy terms, to America's now-hugely popular Lucille Ball. Eventually, in 1956, the commercial channel based in Manchester, Granada, came up with the most ambitious and confident plan: a sitcom, modelled on I Love Lucy, called It's Our Dora.

Written by Reuben Ship (an experienced Canadian dramatist and sitcom contributor who had settled in England after being blacklisted in the US by the House Un-American Activities Committee), this was a genuinely pioneering show in Britain, not only because it was a solo starring vehicle for a woman rather than a man, but also because the first series was set to run for no fewer than thirty-nine episodes over nine consecutive months. No British woman had ever been trusted with anything close to such a major TV comedy project, and it underlined just how highly Dora Bryan was rated by British broadcasters.

It made its debut on Tuesday 18th September 1956. It was well-received, it attracted a good audience, and it was expected to establish Dora Bryan as by far the biggest and most powerful female star on British television (as well as, after selling the package to an American network, one of the best-known British stars abroad, too). The only reason it didn't do so was because tragedy suddenly struck.

Bryan, who had married her childhood sweetheart, the Lancashire cricketer Bill Lawton, a couple of years before, had lost their baby, a daughter, when she had been born prematurely only a couple of months before the show was set to start. Although devastated ('When a woman loses her first baby,' she would later say, 'she feels that the end of the world has come. She feels she will never be happy again'), Bryan made it through the first episode (recorded, with heart-breaking poignancy, on the day her baby should have been due) before she collapsed again, was sent first to hospital and then a nursing home, and the series was abruptly cancelled. ITV, having blocked-out such a long period of time for the sitcom in its schedules, actually hastily revamped the existing scripts to serve as a new show in that slot called My Wife's Sister, but Dora Bryan's well-earned chance, for the moment, had been cruelly taken away from her.

She duly suffered a nervous breakdown, and would not work again for nine months. 'I lost my confidence completely,' she later confessed. 'Frightened of meeting people, dreading pity, I avoided my friends and kept away from the West End. I was taking sleeping pills to knock me out, and pep-up pills to wake me up and stave off depression.'

That ill-fated series was by no means the end, however, of her trailblazing as far as the cause of women on TV was concerned. After losing her second child, who had also been born prematurely, towards the end of 1957 (she would go on to adopt a boy in 1959 and a girl in 1961, before giving birth to another boy in 1962), she gradually recovered her physical and mental health and returned to work, slowly building her confidence back by teaming up with Frankie Howerd for a radio series (Fine Goings On), starring in another theatrical revue (Living For Pleasure), recording several one-off plays for television and taking part in a Royal Variety Performance. Then the TV companies returned and began planning her next possible project.

The aim once again was to find a format as close as possible to I Love Lucy in order to give Bryan the same kind of freedom as Ball to show-off the full range of her comic skills. Several variations were devised but then dropped until, eventually, the commercial channel ABC came up with the vehicle that most appealed: Happily Ever After.

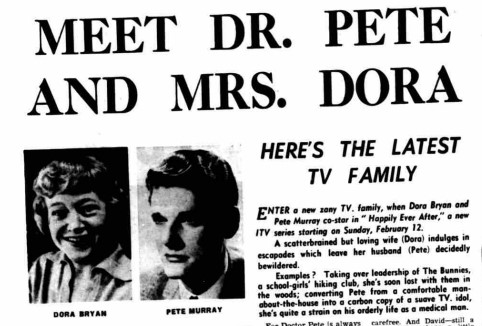

This was a domestic sitcom (written by the British duo of James Kelley and Peter Miller) featuring Bryan as Dora Morgan, a young wife, and Pete Murray as her doctor husband, Peter. Although it was ostensibly about a couple, it was, in reality, very much a starring vehicle for Bryan (indeed, the show would be introduced by her, on camera, and usually also be listed as, 'The Dora Bryan Show' rather than by its official title), with all of the storylines designed to keep her very much centre stage. The affable Murray, who by this time was better-known as a disc jockey rather than an actor, was under no illusions as to his status an Anglicised Ricky Ricardo - 'I'm a Sidney James to her Hancock' was how he preferred to put it - and was perfectly content to serve as her straight man.

Making its debut on Sunday 12th February 1961, it would run for two series over the course of three years (eight in 1961, four in 1964 - the gap was down to her first wanting time with her newly-born baby, and then needing another break to recover from losing another), and did indeed establish her, belatedly, as the biggest female comedy star on British television (and the best-paid comic performer, of either sex, of the time). Sadly, only two episodes are believed to have survived, but it is very easy, when watching them, to appreciate how accomplished her performances were.

The scripts, and the plots, were relatively undemanding and derivative, but Bryan - again much like Lucille Ball - was simply so good at getting laughs, not only with dialogue but also with superbly timed and executed slapstick sequences, that it was impossible not to be impressed by her art. Take, for example, one of the earliest episodes, entitled The Fishing Trip.

This featured a typically contrived and farcical plot that saw Dora try to persuade her hard-working husband to take a holiday with her, only for him to think that she wants him to go without her on a fishing trip with his male friends - which in turn causes her to chase after him dressed as a man. It could easily have been just a mechanical and horribly-laboured affair, but Bryan turns it into something endearingly funny because of the precision of her physical actions and the sheer charm of her key responses.

Joining the all-male group in their cabin as 'Ginger Smith', wearing a ridiculous tartan trapper hat, thick black-rimmed glasses, a tightly buttoned-up jacket, waterproof trousers, thick walking socks and big leather hiking boots while puffing away over-zealously on a pipe, she choreographs the comedy with extraordinary confidence and grace. A big and burly member of the group comes up and shakes 'his' hand, causing her to twist and tip sideways like the arrow on the dial of some kitchen scales before lurching back up and puffing hard again on her pipe. Speaking in a gravelly American accent, she then tries to join in with the bloke-ish banter ('What kind of cigars do you usually smoke, old boy?' 'What kind? Er...brown ones!') before having to swallow a slug of whisky ('Well, here's mud in yer eye!') that makes her fall backwards off the bench.

She remains consistently funny when the roughest and toughest of the men, who tends to shake her around like a rag doll, confides in 'him,' as they sit on a tree stump, that he has made an alarming discovery:

FISHERMAN: You know what this is?

DORA: Er, no.

FISHERMAN: It's a lipstick.

DORA: Yeah?

FISHERMAN: A woman's lipstick.

DORA: Uh...ah.

FISHERMAN: Do you know where I found it?

DORA: Er...no?

FISHERMAN: Back there on the track!

DORA: Oh?

FISHERMAN: Do you know what it means?

DORA: N-No?

FISHERMAN: I think you do. There's no rust or anything - it's just been dropped!

DORA: Ooh.

FISHERMAN: It means that one of us is a woman!

DORA: Er...ha-ha-ha!

FISHERMAN: And I think I know how to find out who it is.

DORA: Oh? How?

FISHERMAN: When they all come back, I'm going to suggest we all go for a little swim in the lake there. And as we haven't got any bathing suits - that should do it!

DORA: And how are you going to tell?

This kind of hackneyed Charley's Aunt-style routine fails to work at all if it's played too broadly (all wide-eyed gurning and fidgeting - the kind of mistake some 'serious' actors make when they stray into sketches or sitcoms) or too straight (which merely makes the absurdity of the situation all the more unfunny and distracting) and it usually is played in one or the other of those styles - but Bryan plays each pose, reaction and expression pitch-perfectly. She was far too good for the material, but it shows what a special comic talent that she had.

The reviews reflected the same sentiment: 'The Dora Bryan Show was very funny, and her reactions to some very awkward situations were extremely amusing'; 'Dora made the most of highly indifferent material'; 'It must be said that Miss Bryan has to provide most of the entertainment value herself'; 'She is consistently more ridiculously funny than her material'; 'She shines in every scene with her peerless comic gifts'; 'It offers more proof, if it were needed, that Dora Bryan is currently Britain's greatest comedienne'.

Once the series was over, she found herself, once again, offered all kinds of projects, ranging from radio shows to West End productions. She cherry-picked the best of them, keeping herself busy with the occasional guest appearance on TV (including the one-off BBC Two show Dora Bryan Entertains in 1964 and, on the same channel, the 1967 sketch series Before The Fringe), a few movies (The Great St. Trinian's Train Robbery and The Sandwich Man, both 1966, and Two A Penny, 1967) and, especially, more theatrical successes (a much-praised role as Nurse Sweetie in George Bernard Shaw's Too Good To Be True in 1965, her own record-breaking revue The Dora Bryan Show in 1965-6 and a long and triumphant run as the star of Hello Dolly! during 1966-8).

There really seemed as though there was nothing Dora Bryan couldn't do. As far as television was concerned, however, she still felt that she had unfinished business.

The BBC, who had been courting her since the mid-1950s in the hope of securing her for a major show, finally got their wish when she agreed to star in According To Dora. The aim was to showcase her versatility more than her previous programmes had done, and a considerable amount of time, money and effort went into bringing the idea to fruition.

Described as a show that 'presents a Bryan's eye view of the world' and introduces 'the new philosophy of laughter' called 'Bryanism', this first series consisted of seven self-contained weekly revues, each one focussing on a particular theme (such as entertainment, love and marriage, commerce and the consumer, home and beauty, or holidays and travel) which was explored via a set of sketches (both filmed on location and recorded in the studio), the odd monologue and a closing comic song.

The writing credits for the show were varied and extensive, and included Alan Melville, John Law, Dave Cumming, Willis Hall, Bob Block, Ronald Chesney and Ronald Wolfe, Dick Hills and Sid Green, John Junkin, Marty Feldman, Eric Idle, Keith Waterhouse and Harold Pinter. The supporting cast, which changed from week to week, was similarly large and impressive, with the likes of Terence Brady, Joan Sims, Patricia Hayes, Diana King, Wilfrid Brambell, Kenneth Connor, Hugh Paddick, Clive Dunn, Deryck Guyler, June Whitfield and Eleanor McCready all contributing to the sketches.

The sight of a woman starring in such a lavish and high-profile BBC show clearly rattled some of the more misogynistic among Britain's male TV critics, who were already reeling from the progress being made by the Women's Liberation Movement at that time. William Marshall, for example, in a quite extraordinarily sexist rant in the supposedly left-of-centre Daily Mirror that read as though it had been written in 1868 rather than 1968, began his review (such as it was) of the first episode by announcing that a woman 'has very little place in her mind, in my experience, for humour or slapstick, because basically she is made to take care of the big things in life, like eating, feeding children, and making herself attractive to the male. Having all these gigantic things to go at, a woman's attempts at humour for me usually go astray'.

Having rapidly ejaculated this unappealing opinion, Marshall then proceeded to demonstrate some obvious confirmation bias when he finally got around to discussing the show itself: 'The excruciating lack of humour in this programme was so monumental as to make it a viewing must next time around. Sort of a collector's piece'.

Another critic - the very experienced Kenneth Baily in The People - sounded as though he was heading down a similar knuckle-dragging route by starting his review as follows: 'Funny women are about TV's rarest commodity. Try naming memorable comediennes. There's Dora Bryan. Then there's...Dora Bryan. And there's...er...Dora Bryan'. He went on, however, to stress that he was not condoning the dearth of female comics on television but merely noting it, and said that Bryan's brilliance was, in those circumstances, especially invaluable and also potentially very inspiring to other women.

The vast majority of critics, in fact, who had managed to escape from the over-long shadows of the Victorian age, were quick to praise According To Dora. 'A very funny show - excellent performances and excellent writing'; 'The quick sketches were some of the funniest I have seen on television'; '[The show is] one of the successes of the year'; '[Bryan] is extremely funny and extremely professional. A joy to watch'; and 'Native wit and captivating gaiety have combined to put Dora Bryan in a class of her own. According To Dora is a credit both to the star and her scriptwriters'.

The series started with an impressive enough audience of 9.5m (which put it sixth in that week's national top ten, and made it the BBC's most-watched programme of the period), and then built up such momentum that, by the time it finished, it was already being acknowledged as one of the BBC's most successful shows of the year.

It was, unsurprisingly, back the following year, from Friday 2nd May 1969, for a second series. The reception, once again, was generally excellent.

One might have assumed that the Daily Mirror's William Marshall had by this time abandoned the profession of criticism in favour of wandering about the English countryside trying to catch a stray woman with a butterfly net, but, no, he was still firmly in situ, and as unimpressed as ever by According To Dora: while admitting that 'Dora Bryan can be gigantically funny,' he moaned once again about the 'weak, hackneyed pieces' and complained when in one sketch her character was seen to wear 'heavy silk bloomers'.

Much more representative were the reviewers who wrote that Bryan 'always sparkles', her material was 'very funny' and the series as a whole was 'a pleasant change' from the normal male-dominated comedy output and was 'high class entertainment'. The show also performed well in the ratings again, and a special forty-five minute 'highlights' edition, shown later in the year on 27th August, fared especially impressively.

There would not be a third series - the show had been expensive to make for the BBC, and Bryan wanted to end the run on a high - but its legacy would not only be to further enhance the star's own reputation but also to encourage more interest, and faith, in broadcasters giving female comedians the chance to shine in their own right, rather than merely in supporting roles alongside men. From this point on, after more than a decade of trailblazing, any talented woman in comedy, when her ambition was ever doubted, had access to an incontrovertible answer: 'Well, Dora Bryan did it'. There was no going back after what she had achieved.

As for Dora Bryan herself, she carried her remarkable success on into the 1970s. She was persuaded to make another sitcom, this time for London Weekend Television, in 1972. Called Both Ends Meet, it featured her as Dora Page, an impoverished widow with a teenage son, an elderly father-in-law and a job working in a sausage factory (hence the show's punning title).

It was devised by the quartet of Brian Chase, Len Downs, Mike Firman and Patrick Radcliffe, who, rather ominously, were devotees of a fleetingly fashionable new algorithmic method of 'calculating' TV success, called 'Television Audience Programme Evaluation' (or 'TAPE' for short) which focussed on such factors as the popularity of the star, the secondary actors, the setting and so on, and then delivered a commercially-viable package, as if it was supplying a fresh flavour of crisps or a new brand of chocolate bar. It was evident, however, that Bryan had also played a part in the shaping of the sitcom, having discussed the dynamics and relationships very carefully until she was satisfied with the basic structure. 'Being a widow gives me scope for romance,' she reasoned. 'The son is good for pathos. And having a father-in-law is better than having a father because it shows you're a warm-hearted lady.'

The problem, however, was that, in stark contrast to her previous show on the BBC, ITV (in spite of all the hype about hiring TAPE) adopted the same 'cheap and cheerful' approach to this sitcom as it was already using for most of its other comic output of the time, relying heavily on the ability and appeal of its star to compensate for the creakily conventional material - and, once the series started (on 19th February), the critics recognised it straight away. 'The situations are contrived and the gags are corny,' wrote one, while others - noting that even the decision to feature a sausage factory seemed like a lazy way to tap into the popularity of ITV's most-watched sitcom of the time, Nearest And Dearest, which featured a pickle factory - complained that it was 'quite unashamedly aimed at the lowest popular denominator of the viewing public'.

The show, none the less, did well enough in the ratings, and so returned for a second series later on in the same year. This time, however, it responded to the obvious fact that this was a starring vehicle for Bryan rather than a bona fide 'family' sitcom - 'This is a one-woman show,' one reviewer had written, 'in spite of the presence of other reliable performers' - by renaming it Dora.

The team of white-coated knob-turners and button-pushers at TAPE made other changes to the sitcom, moving the action away from the sausage factory and focussing instead on Dora's home life, recast one of the other roles, and hired a new set of writers. Bryan, however, was so unimpressed by the 'improvements' that, even at the launch party, she told reporters, 'It still doesn't stretch my talents'.

Sure enough, the show limped on without much coherence or conviction. 'Given the talents of its star,' wrote one observer, 'it has tended not only to waste them but [also] in a sense to diminish them by putting them to poor use.'

Not liking the direction that television now seemed to be heading, Dora Bryan grew more than a little disillusioned with the medium after this experience. She continued working, especially on the stage, but she also devoted an increasing amount of her time to running her family's sixty-room Brighton seafront hotel - Clarges on Marine Parade - which she had bought in the Sixties (and was featured in the exterior shots for Carry On Girls).

There would be difficult times during the next few years in her personal life - including struggles with alcohol, financial worries, the premature death of her daughter, a debilitating disease for one of her sons, and another nervous breakdown (all of which, as usual, would excite the tabloids far more than anything to do with the travails of talent) - but she eventually re-emerged to once again show her rare worth as a performer.

There were dramatic and comic roles, and some major theatrical engagements (at one point in the 1980s she was starring in two shows simultaneously - The Apple Cart, alongside Peter O'Toole, and the musical Charlie Girl, with Cyd Charisse - which required lightning-fast costume changes and waiting cabs to manage both curtain calls each night). There was also the odd guest appearance in television series such as dinnerladies and Absolutely Fabulous, and in 2000 she became a regular member of Last Of The Summer Wine, playing Ros Utterthwaite alongside her old friend Thora Hird for the next five years until ill-health intervened.

She died, aged ninety-one, on 23rd July 2014. Having been out of the public eye for some years, the coverage of her passing was respectful but rather modest for someone who had achieved so much.

Bryan had once joked that she could have won far more honours and awards if only she'd spent more time creating 'a bit of an aura' around herself, which, sadly, is probably true, but says far more about the shallowness of society than it does about her own self-effacing decency. She should not have needed to have been a relentless networker and persona promoter to have received all of the regalia that she merited. She had earned it, fair and square.

The time since she passed away has seen her name fade even further from the cultural consciousness. In the BFI's supposedly authoritative list of the 'ten peerless funny women of British TV comedy', for example, she is nowhere to be seen, which is as shameful as it is ridiculous.

Dora Bryan deserves far better than this. Her importance in the history of British comedy can hardly be overstated: a master of every medium, and a trailblazer especially in TV, she was one of the first women to star in her own prime time television show, one of the first to star in her own revue show, the first to star in her own sitcom, the first to have a succession of starring vehicles - she helped break through one glass ceiling after another, and coped with all the cuts that came with them. She battled and beat the bigots, she challenged and changed expectations and she charmed the broadest audience.

She was funny, she was versatile, she was smart and she was brave. Every single woman who works in comedy today owes her an inestimable debt, and everyone who cares about British comedy should remember her, and respect her, and celebrate her as one of the true greats.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more