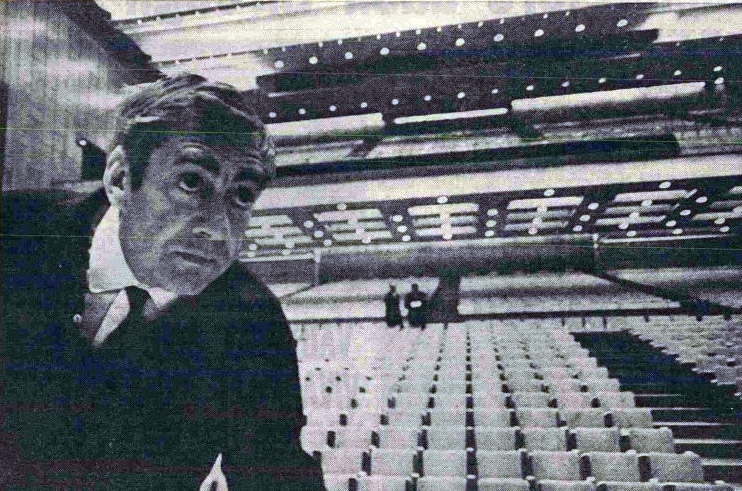

Tony Don't Fall Backwards: Hancock at the Royal Festival Hall

'Here's one for the teenagers...' It is a line that gets trotted out whenever anyone wishes to joke about their own 'outdated' reference, but the irony is that, for many, the origin of the phrase itself has long been forgotten. It was actually first said fifty-five years ago this month, in circumstances that were quite strikingly tragi-comic in nature.

The line was uttered by none other than Tony Hancock, on 22nd September 1966, on the stage of the Royal Festival Hall. It came during his comeback concert, his last real shot at redemption, and sounded so painfully, as well as playfully, self-aware that it seemed to know that tears were as relevant as laughter.

It cannot be understood fully simply by watching it back as it happens. One also needs to know the story behind it - a tale taut and twisted by ambition, addiction and passion - because so much of the past was pressing down on the present that night, lending a particularly poignant meaning to a line like that.

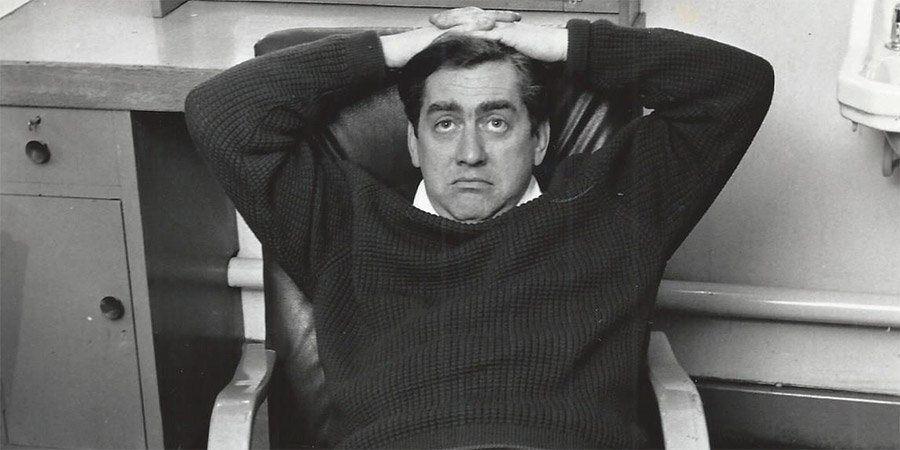

As far as the ambition was concerned, it was about the desperate attempt to claw one's way back up the cliff face. Only a few years before, Tony Hancock had been Britain's most popular comedy star. On radio and then on TV, his sitcom Hancock's Half Hour had become a national institution, and his character had become a national icon - Anthony Aloysius Hancock, the quintessential lower middle-class misfit, the perfect comic symbol of chronic self-delusion.

Then, without really knowing it, he started to throw it all away. First he tried to prove that he could do it without most of his supporting cast - so Bill Kerr, Hattie Jacques and Kenneth Williams were left behind. Then he tried to prove he could do it without his main sidekick, Sid James - so he, too, was left behind. Then he tried to prove he could do it without his writers, Galton and Simpson - so they, too, were left behind.

He dreamed of being another Chaplin, another Tati. He dreamed of being an auteur.

The dream, however, kept being dashed. While the likes of Jacques, Williams and James had gone on to enjoy greater prominence and popularity on TV and in movies, and Galton and Simpson were now revelling in the success of Steptoe And Son, Hancock had suffered one disappointment after another, and his star was in steep decline.

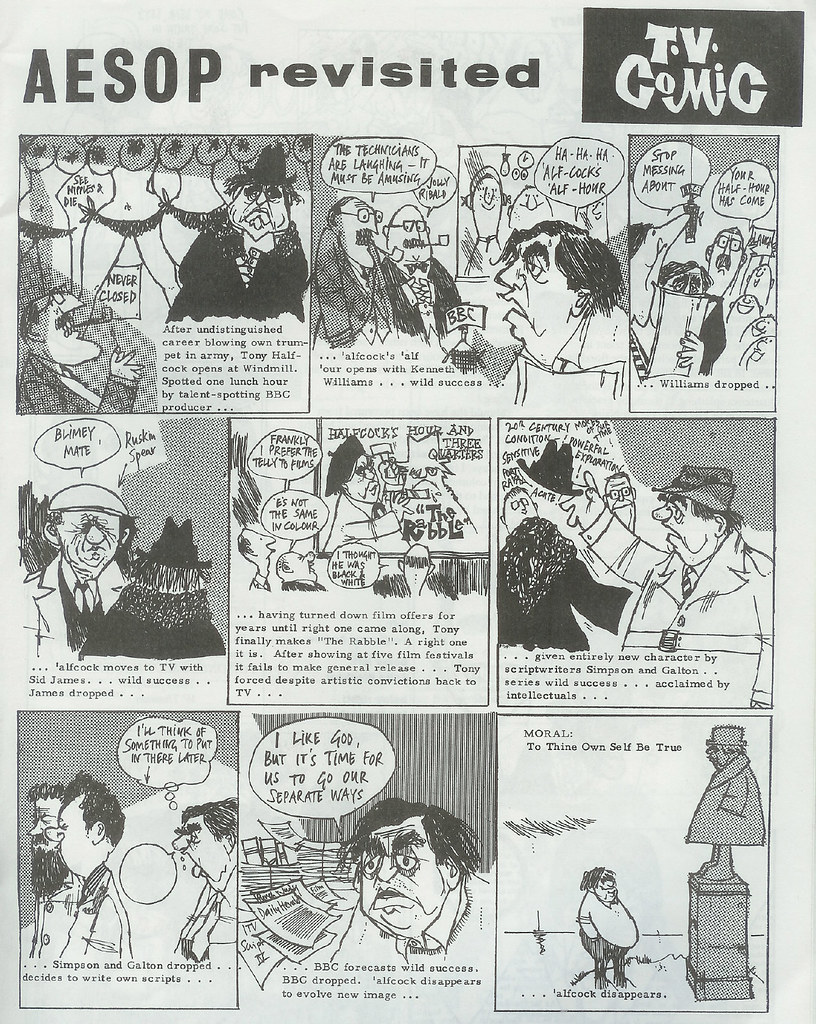

Private Eye, cruelly but pertinently, had recognised what was happening as early as 1962, when the magazine published a cartoon strip about a TV comic called 'Tony Halfcock' - a rapidly-developing megalomaniac who eventually dismisses everybody ('I like God, but it's time for us to go our separate ways') and ends up lost in the shadow of his own statue.

This, increasingly, was the image that was being imposed on to Hancock himself. By the middle of the decade, he had not only cut his ties with his old colleagues but also severed his connection with sitcoms as well. 'I feel I must forget situation comedy,' he told a reporter at the start of 1966. 'So many other people are trying it and there is a limit to the number of ideas and changes to be used.' There was a perception of him, as a result, of being strangely rootless and directionless, unsure of how best to recover some momentum.

He had tried and failed to make his mark in America. Both of his movies, The Rebel (1961) and The Punch And Judy Man (1963), had flopped on that side of the Atlantic, with one influential New York critic, Bosley Crowther, dismissing him scathingly as 'every bit as low' as Norman Wisdom 'and even less comical'.

It had been the same story on US TV. Imports of his old shows had fallen flat for American viewers, and an attempt at making a US-style TV series (modelled, he would freely admit, on The Andy Williams Show), in which he would 'chat to the audience, introduce a guest or two, try interviewing, work in a couple of sketches, and add a little music', failed to come to fruition after he first mooted it in 1965.

He had also tried and failed to revive his career in Britain. The most recent attempt, in the summer of 1966, saw him agree (at short notice) to host an ITV variety series called The Blackpool Show (for a fee no bigger than the ones he was receiving back in the mid-1950s), but the move backfired badly. Burdened by sub-standard stand-up material and unsuited to the role of an MC, he appeared unhealthy and ill-at-ease, being heavily reliant on the idiot boards that were positioned in the wings and the orchestra pit, and his stumbling performances (along with his unplanned absence from one episode because of 'stomach trouble' - he was actually being sedated in a nursing home - and all of the negative publicity that came with the news that his long-suffering wife had been rushed to hospital in a coma after taking a drug overdose) only reinforced the view of him as a burnt-out and unreliable star.

'Hancock's attempts at humour were pathetic,' complained one particularly unimpressed critic, 'and instead of the comeback we hoped for, on this showing alone his career is reduced to ashes.' Another self-proclaimed 'embarrassed fan' of the 'one-time top comedian' asked the question: 'How long is this fast-disappearing comic going to fool about with his career?'

All Hancock had left, after this disappointment, was the prospect of a very prestigious one-man show at the Royal Festival Hall a few months away in the autumn (secured for him, after much pleading, by his old friend and patron Bernard Delfont, and slotted in the schedules between a concert by the London Mozart Players and a screening of La bohème). This, he realised, was his one real chance to put things right. This was the last throw of the dice.

The ambition, therefore, had not yet been extinguished, but one of the things that had been undermining it for some time was an addiction. Hancock was now an alcoholic.

He had always been prone to depression and self-doubt, but for the past few years he seemed unable to cope with the pressure without reaching out for the alcohol. It was rumoured that, on a number of occasions, he had drained the best part of a bottle of brandy before going out on stage, and some sources claimed that he had started drinking through the day as well as the evening as his discipline continued to decline.

There had been no respite when Hancock was at home, because his first wife, Cicely, had taken to drowning her own sorrows on a regular basis, rationalising her behaviour by saying, 'What goes down my throat does not go down his'. Early in 1958, soon after the couple had left London for what both of them hoped would be a healthier new home in the country - an attractive property at Lingfield in Surrey that they christened 'MacConkey's' - they invited several of their close friends down for the house-warming party. 'It's okay,' Hancock announced brightly, 'the drinks will be arriving any minute.'

Sure enough, a short while later, a three-wheeled van turned into the drive and pulled up at the front door: it was loaded to the roof with case upon case of vodka. Back inside, Cicely handed everyone a beer mug and Tony proceeded to fill them all up to the top: no tonic, no lemon, no ice - just a full pint of neat vodka.

His second wife, Freddie, whom he married in 1965, had tried valiantly to keep him from his demons, but to no avail. He remained in the grip of drink, sometimes disappearing on binges for days, and, as his career continued to decline, so, too, did his health as he drifted in and out of specialist clinics and nursing homes.

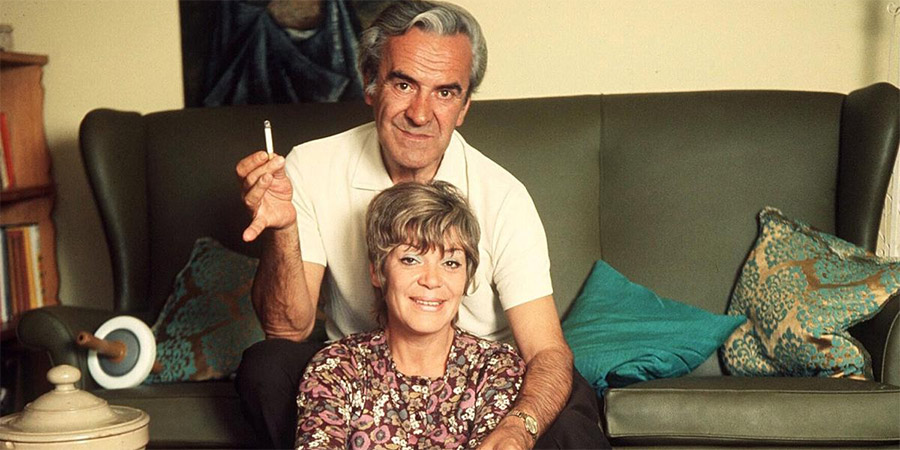

It was at this stage that the ambition was compromised not only by an addiction but also by a passion. Hancock had embarked on an intense, and very complicated, affair with the wife of his best friend, John Le Mesurier.

Le Mesurier had actually introduced his then-girlfriend, Joan Malin, to Hancock back in 1964, soon after they had started dating. As they relaxed together over dinner at a local pub, Hancock had nodded at Joan and said to John, 'You've got to keep this one, Johnny'.

It was during the summer of 1966, a few months after John and Joan had married, that Hancock's relationship with both of them started to change in the most dramatic of manners. One Sunday evening, a dramatic telephone call came suddenly from Hancock begging John urgently for help. He and his second wife had finally broken up, and he had shut himself away in his Knightsbridge flat with just a single upright chair, a bed and a mound of empty bottles. He had, he explained, gone for days without opening the door or picking up the telephone, but now, with the prospect of his high-profile Festival Hall concert (which was also set to be recorded for posterity by the BBC) plunging him into a state of panic, he desperately needed company and support.

Le Mesurier, unhesitatingly, rushed off to collect his friend and brought him back to stay with him and Joan in their own London home at Barons Court. As he came bounding through the door of the flat, with a broad and almost manic grin on his face, Joan was shocked to see how ill and gaunt he now looked, but she was happy, as she later put it, 'to have the chance of mothering him'.

He remained there for just over a week, sleeping on the couch and wandering around wearing John's dressing gown. He did not eat much, but he drank a little and talked a great deal and seemed to relax in the company of a couple he trusted.

With John usually spending the evenings learning his lines, Hancock would sit in the kitchen with Joan, chatting about a wide range of things, leaping up whenever she rose and following her around 'like an amiable bloodhound'. 'He never flirted with me,' she would say. 'The idea of him flirting with anyone would have seemed ridiculous. But he was just very "fixed" on me.'

The following Monday morning, after John had left early to begin work on his latest movie at Borehamwood, Hancock, in a rare moment of honesty and self-awareness, sat in the kitchen with Joan and asked her, 'Do you know that I'm an alcoholic?' She replied that she had always suspected that he was. He then went on to explain that his agent had arranged for him to go into a nursing home in Highgate to dry out before commencing a week-long run at the Bournemouth Winter Gardens, where the aim was to rehearse some new material (supplied by his current writers John Muir and Eric Green) intended for the big event at the Festival Hall.

Seeing how nervous he was, she agreed to accompany him in his car to the clinic, and she sat with him in the waiting room sipping tea and munching on biscuits. 'How romantic,' he said with a wry smile, 'our first meal alone together.'

Just before he was taken inside for the treatment to begin, he made Joan promise that she and John would visit him that night. The two of them did so, but were told that Hancock was currently under sedation and unable to see anyone, so they returned home and spent the remainder of the evening talking about the man who was now very much their mutual friend.

Once Hancock was out of the clinic he went straight down to Bournemouth to prepare for his show. The following week, John was told that he was needed in Paris to shoot some location shots for his latest movie, so Joan saw him off at the airport and then went back to Barons Court.

She was making plans to spend a short period away in Ramsgate with her son and parents when the telephone rang. It was Hancock, asking if he could come back to stay for a few days with her. Joan tried to explain that, as John was away, she was about to take a break, but he persisted. 'Look,' he said, 'I'll be out all day. I'm rehearsing for this show and it's scaring the shit out of me. I'm sure John won't mind.' Joan relented and told him that he could visit.

She was hosting a small dinner party that evening for a few friends, and, when Hancock arrived, he charmed all of her guests and then, when they had left, he charmed her. After sharing another bottle of wine, they started to look at each other intently, sensing that, unless they were careful, something dramatic could well be about to happen. Eventually, Hancock decided to make a move, kissing her passionately. 'I'm John's best friend and I'm in love with his wife,' he then exclaimed. 'What are we going to do?' Joan simply said, 'Let's sleep on it'.

Who seduced whom? 'It was mutual' Joan would tell me. 'Well, he made the first pass. And I told him to stop because I knew I was falling for him and just couldn't fight him. But he became so romantic, saying he wanted to marry me, give me babies, move to the country...all of those things.'

The two of them woke up the following morning convinced that, as sudden as it was, they were now firmly in the grip of 'a grand passion': 'In one single night,' Joan would later reflect, 'Tony had become the centre of my life and his happiness was my first priority.'

The world, for them, seemed to stand still and silent during those next few days. The doors stayed shut, the telephone was left off the hook, and the couple remained in bed, finding out all they could about each other. It was the most intense kind of reverie.

Reality then rudely intruded one morning when a postcard arrived from John. 'Here I am in Paris, France,' it read cheerfully. 'Can't wait to get home to my little friend and wife.'

Both Hancock and Joan suddenly seemed to wake up and take in the enormity of what had just happened. Joan said that she simply could not bear to hurt John after all that he had been through with his two previous marriages, and so the affair, if it was to continue, would have to remain a secret. Hancock, however, refused to agree: 'It wouldn't be honest,' he insisted. 'It would make John more unhappy in the long run.'

He suggested that he should take responsibility and talk to John face to face, but this only made Joan even more agitated and she begged him for more time in which to think. She decided to call a close female friend for advice, perhaps hoping that rational intervention would shame her into doing the decent thing, but, when the friend came to see them at the flat, she, too, was soon charmed by Hancock and ended up urging Joan to make a clean break of it and go off with her lover.

Joan, however, was still wracked by doubts. 'I kept thinking about John's gentleness and his love for Tony,' she would explain. 'I felt as if I were about to commit a murder.'

Hancock simply refused to relent, and telephoned his mother, explaining what had happened; he then handed the telephone to Joan, so that his mother could tell her to choose her son. The pressure on her was, in both senses of the word, remorseless.

Joan would later claim, rather generously, that, in her opinion, Hancock was so impatiently manipulative mainly because of his desperation to drive away his own great sense of guilt: 'Tony was as horrified at the thought of hurting John as I was; yet he was equally horrified at the thought of losing me. By convincing others, he was trying to convince himself that he was right. He pulled out every stop and in the end John's fate was sealed.'

Joan said that she needed to be alone when she talked to John, so Hancock moved out the day before he was due to fly back from France. Taking another female friend with her for emotional support, she met John at Heathrow and, after he had handed the two women gifts of perfume from Paris, they went off to a restaurant for dinner.

It did not take long, predictably, before John asked Joan if she had heard from Hancock. Trying hard to seem casual, she mentioned his rehearsals for the imminent show at the Festival Hall and then quickly changed the subject.

The conversation continued for a while until, unable to bear the strain of trying to seem 'normal' any longer, Joan complained of feeling tired and, cutting the evening short, John took her home to Barons Court. Once inside, she broke down immediately and told him what had happened.

'Even then,' she would later reveal, 'he didn't get angry - it would have been so much easier if he had. He just walked up and down hugging himself, and then he wept.'

Once the tears had subsided, she gave him a sleeping pill and got him into bed and then prepared herself for a long and painful night alone with her thoughts. The following morning, she arranged for a mutual friend to come over to comfort John, and then she left the flat and set off to see Hancock.

He had installed himself in the opulent Maharajah Suite at the Mayfair Hotel, and, while he waited anxiously for Joan to unburden herself of the truth, he had started drinking (and, with the craven crassness of an addict, had called his estranged wife to inform her: 'I have found someone younger and prettier than you'). By the time that Joan arrived, he was very drunk, in tears and on the phone to, of all people, John.

'You've got to go back to Johnny,' he shouted over at her and sobbed. 'I can't bear it - you've got to go back to him.' When Joan hugged him, however, he hugged her back, and, quite predictably, the telephone was put back down. Such brief and isolated contrition was typical of Hancock in this sort of state: it slid out of him like the dregs at the bottom of a bottle, merely leaving more space to be filled by a fresh draught of self-serving thoughts.

Back at Barons Court, John - who had ended the call from Hancock by doing his best to console Joan - was still in a profound state of shock. 'There was nothing I could say or do,' he would later reflect, 'because nothing made sense to me.'

As the days went by, and some of the shock subsided, he tried hard to rationalise how his 'little friend' had behaved: 'I think she felt, rightly or wrongly, that Tony needed her more than I did, that she could be a steadying influence on him - even that she might eventually stop him drinking. She also felt that if he could regain his professional confidence, then all would be well'.

John, however, had lived through such a scenario himself during the latter part of his own first marriage to the theatre director June Melville (who had also become a chronic alcoholic), so he could not help but now feel that Joan was bound to end up being similarly, and very cruelly, disabused: '[L]ike all alcoholics, Tony was really two people. He was the life and soul of the party, the funny man who inspired love and affection, the generous friend who sought approval and desperately wanted to be liked. And he was the drunken braggart whose black moods of self-loathing almost always ended in violence and abuse directed at those who loved him most'.

In the immediate future, however, there was no time for much reflection, because Hancock was obsessed with his make or break date at the Festival Hall and Joan was desperate to get him into the right frame of mind to turn it into a triumph. Once again, his ambition was fighting against his failings and driving him on.

Dogged by fears that the event would prove a disaster, however, he fussed over every detail, rehearsing with far greater effort and care than he had invested in a performance in years. 'He was trying so hard,' Joan would tell me. 'Trying to keep out the doubt, trying to keep in the hope, trying to keep believing in himself.'

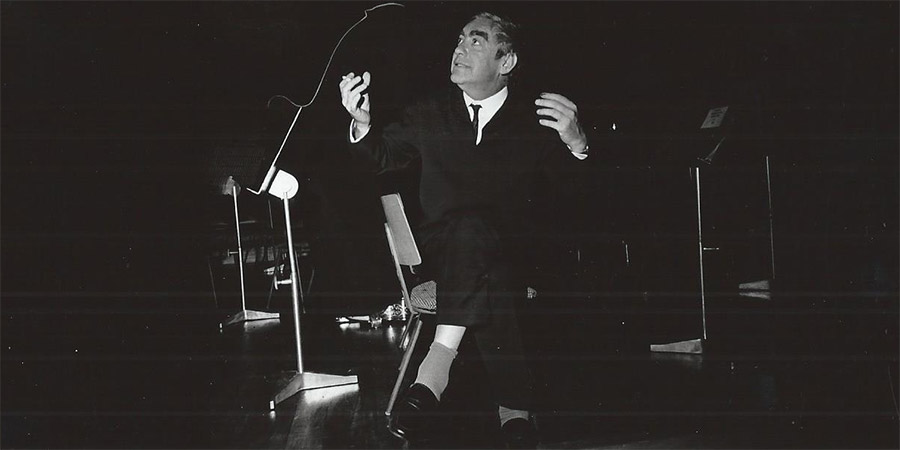

Sometimes it sounded as though he was thinking of the concert as his swan song (he spoke of 'going out with a bang and not a whimper') while at other times he talked animatedly about all of the brand new beginnings it could create, but, one way or another, he was clearly committed to confounding all of his critics and conjuring up something truly special. When the moment finally arrived, however, he failed to do anything that discouraged suspicions that his career was already in terminal decline. He had worked so hard to sell the show that he had over-sold it to a catastrophic degree. He had promised to be at the top of his game, bursting with energy, in a performance that would be full of fresh and funny material. None of that would turn out to be true.

Panicking in the last few weeks and days leading up to the performance, he had reached out to his old friends and colleagues, the ones he had so callously left behind, in the hope that they would now race to his aid. He had called Galton and Simpson to ask if they would write him a new sketch. They declined. He had also tried repeatedly to contact Kenneth Williams to see if he would reprise the RAF pilot sketch from Hancock's Half Hour ('It ain't half cold out here, can I come in?'), but the actor had refused to return the calls ('He must be either very stupid or mad,' he said to his Carry On colleagues). Hancock had no choice but to keep shuffling what fragments he already had, mixing the recent with the ancient, desperately trying to hit on the best, or least worst, sort of order while the clock kept on counting down to the big day.

When the big day did indeed arrive, he was in a strange state of mind. 'Ring your Dad,' he asked Joan just before he stepped through the stage door, 'and find out if there's a vacancy for a crane driver in Ramsgate. I'm going to be out of a job tomorrow.' He wasn't smiling. Joan would recall that he resembled 'a small, brown bull going in to the arena to meet his end'. She was intensely worried about him. He had already warned her that, if things were going badly during his act, he would be sorely tempted to bring the proceedings to a sudden halt and deliver a farewell speech that would begin, 'Ladies and Gentlemen, as I'm obviously dying a death up here, I'm not going to bore you any more with this load of old rubbish...' She was genuinely afraid that such a breakdown might happen.

When the event commenced at 8pm on that cool and cloudy September evening, in front of a packed audience of three thousand expectant people, there was immediately a sense that it was going to be a strangely amateurish occasion. Many of the paying customers, for example, were surprised and disappointed to discover that they were going to have to sit through a ninety-minute first half that was to be completely Hancock-free.

They knew that Marion Montgomery, a popular American jazz vocalist of the time, was set to sing a few songs with the musical accompaniment of Tony Hatch, but few had expected that they would have to wait one-and-a-half hours before the comedy finally started. Hancock, who was sitting in his dressing room listening via a loudspeaker, could hear the growing sound of restlessness amongst the audience as Montgomery battled through a succession of technical problems. Fearing what kind of mood they would be in once he finally appeared, he promptly vomited in the sink and started drinking his way through a whole bottle of brandy.

When, at long last, it was finally time for 'The Lad Himself' to appear, neither he nor the audience was in the right frame of mind for what would follow. Hancock himself, emerging to the sound of 'Mr Wonderful', looked emaciated, ashtray grey and terribly strained.

Everything, from that point on, seemed jarringly half-thought-out, with the audience left to interpret what was supposed to be 'funnily' pathetic and what was just plain pathetic. His outfit, for instance, was, presumably, meant to look as bad as it did - an ill-fitting suit jacket, overly-short trousers, white socks that, bizarrely, resembled spats and a pair of dark leather loafers - but it was never really clear why it was meant to look as bad as it did. He just seemed badly-dressed.

It was the same with his material. With a delivery that was sluggish right from the start, he started out by sticking to the Muir and Green script (which he performed with plenty of squinted stares at his cue cards hidden in the wings) but quickly lost confidence in it and subjected those who were present to a selection of career 'highlights' instead - most of which dated back at least a decade.

The most painful section, in this sense, was when he resorted to performing a set of knowingly incompetent impressions. First up was the actor Robert Newton (who was ten years dead) - 'Ha-aaaaarr, Jim, lad...' - followed by Charles Laughton (four years dead) - 'Mr Christian...'. The audience, sounding confused as to whether this was meant to be taken as a 'so bad it's good' routine, or just a bad routine, were forcing a few laughs, but there were plenty of puzzled-looking faces. As if on a whim, Hancock then said, by way of a cold sweat quip: 'Here you are, here's a cracker - one for the teenagers!' He then launched into his ancient impersonation of the actor George Arliss (twenty years dead), which was not so much an impersonation as merely a five-second mime. Staring out glumly into the darkness, he said: 'What do you mean, you've never heard of him? He's only been dead forty years!' It was as if Hancock was alternating between poking his audience, and himself, with a sharp stick.

With his once-expressive face now stiff and slow, and his fine comic timing no longer truly sharp, his worst impersonation of all that night was of the great Tony Hancock in his prime. The friendly audience had done their best to respond warmly to his efforts, but, when a recording of the show was screened the following month on BBC Two, the painfully pedestrian nature of the performance was exposed for all to see ('I saw that load of crap you did on the telly,' a taxi driver told him the following day. 'Well, I'm not mad about the way you're driving this cab,' snapped Hancock). Even Joan would later acknowledge that much of the applause on the night had been down to 'pure nostalgia, a thank-you for his past glories'.

If it happened today, some people might try to spin the whole sorry thing as an elaborate post-modern joke, a car crash in quotation marks, a sort of brave and artful meditation on tired and aimless naffness, but, back in 1966, it was no such thing. It was just, plain and simply, a depressing mess.

The 'Here's one for the teenagers' line was merely the most open and incisive instance of the bitter self-critique that Hancock had woven through most of the show. Here was a once-great comic, trying and failing to again be that great comic, and reflecting and commenting on that failure as it was actually happening. Instead of raging at the dying of the light, he was distracted by the lengthening shadows that were being cast across the stage.

This was really the end of his career. He would do other things in the eighteen months or so that he had left of his life - another half-hearted variety show called Hancock's, a movie for Disney (The Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin) from which he was sacked, and, of course, his ill-fated and incomplete series for Australian TV - but he already knew, on that stage at the Festival Hall, that the magic - his magic - had well and truly gone.

Anyone, therefore, who today is tempted to use that old line, 'Here's one for the teenagers,' in a lazy and throwaway manner, might think again and perhaps leave it alone. Hancock, when he said it, was - as another over-used phrase would put it - not waving but drowning.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreThe Tony Hancock Collection

This collection contains all 37 surviving episodes, from 1956 to 1961, of the classic TV sitcom written by Galton and Simpson, featuring East Cheam's most famous resident, Tony Hancock, alongside supporting stars including Sid James and Kenneth Williams.

Sadly, 17 episodes from the series are missing believed wiped, but their scripts are included in PDF form amongst the set's extras.

First released: Monday 22nd October 2007

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 8

- Minutes: 1,083

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: BBCDVD2168

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.