Utterly Buffery - The short but special comic career of Tony Buffery

Tony Buffery was, in comedic terms, the one who got away. He was part of the golden Cambridge Footlights generation that went on to help create I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again; I'm Sorry I Haven't A Clue; At Last The 1948 Show; Broaden Your Mind; Do Not Adjust Your Set; Monty Python's Flying Circus; The Goodies; Rutland Weekend Television; Fawlty Towers; and Yes Minister.

He fascinated John Cleese, who marvelled at his fearlessness. He astounded Eric Idle, who described him as 'the most inventive cabaret talent ever,' with 'an ear like Peter Cook and a mind from outer space'. He delighted Clive James, who said that he 'made people laugh until they ached'.

While the others left Cambridge, however, and pursued their various individual and collaborative careers in comedy, Tony Buffery stayed behind, trained as a neuropsychologist, and remained in academia. The others went on to write about dead parrots, giant kittens, funky gibbons, four Yorkshiremen, three heads, two legs, one mistaken messiah, Mornington Crescent, nudge-nudges and wink-winks, SPAM, sperm, Scottish hospitality, self-defence against fresh fruit, cheeseless cheese shops, Lancastrian martial arts, mad hoteliers, The Rutles and Arthur 'Two Sheds' Jackson, but Tony Buffery went on to write about 'Sex differences in emotional and cognitive behaviour in mammals including man,' 'Brain function therapy: Computerised neuropsychological rehabilitation' and 'Learning and Memory in Baboons with Bilateral Lesions of Frontal or Inferotemporal Cortex'.

How on earth did this strange bifurcation happen? One may as well start at the very beginning.

Anthony Walter Harold Buffery was born in Birmingham on 9th September 1939. The son of Winifred, a secretary, and George, a railway worker, he was educated at the local Moseley grammar school, where he not only shone academically and athletically but also acquired a reputation as a wildly unpredictable and largely uncontrollable comic performer in serious as well as light-hearted plays.

He could dream up the most unlikely and intriguing and sometimes disarmingly silly ideas, such as radio shows full of mime; he could suddenly burst into song about the most surreal of things; he could mimic his masters and mock their attempts at scholarly mystique; and he could leap about doing comic dances, pratfalls and silly walks; he could react to a single word by spinning it into a spiral of madcap laughs. More than half a century later, many of his fellow Old Moseleians would still be able to recall him having 'us all in fits as he ad-libbed his way across the school stage'.

He studied for his first degree at the University of Hull before commencing his doctoral research in 1960 at the University of Cambridge. Under the supervision of Dr Lawrence Weiskrantz (who would later be credited with discovering the phenomenon of blindsight), Buffery's principal focus for the next three years would be on 'The effects of frontal and temporal lobe lesions upon the behaviour of baboons'.

It was quite an enterprise. No fewer than nine East African baboons (none of them aged more than eight months) were imported to The Fens, given names (Li'l Abner, Orc, Houdini, Chunk, Freckles, Tock, Tick, Hobbit and Chips) and then separated into groups of three (one receiving bilateral lesions within the dorsolateral frontal cortex, another bilateral lesions in the inferior temporal cortex, and the other, luckily for them, serving as the control group). It would eventually be found - spoiler alert - that 'the temporals have difficulty in retrieving classified visual information from storage,' with the results also supporting 'a modified disinhibition hypothesis of frontal impairment'.

As he would come to note, with uncommon graciousness, Buffery basked throughout this time in the 'warm personality' of the always-supportive Weiskrantz: 'For many days,' he wrote at the front of his thesis, 'I have been trying to think of a suitable acknowledgement for all the guidance Dr Weiskrantz has given me - for the knowledge he has imparted - for the successful surgery he performed upon my baboons - for giving me his time, thought, effort and, above all, his friendship - but a suitable acknowledgement, couched in such terms as "without whose help..." or "he taught me everything I...," seem both inappropriate to the man, and insufficient to the debt'.

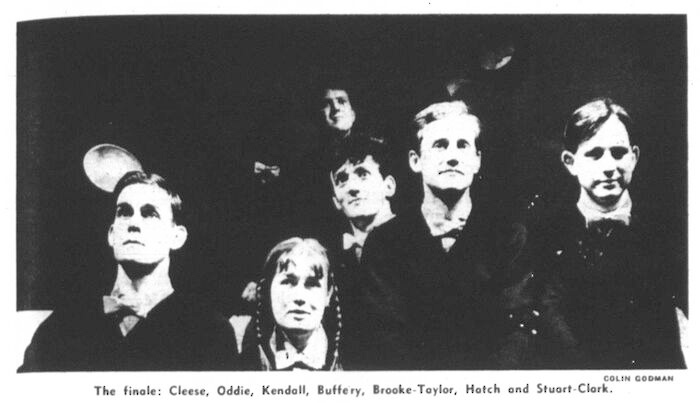

It was in part due to the thoughtful indulgence of this good-humoured supervisor - who never liked to see his young researchers be submerged too deeply, for too long a period, in their studies - that Buffery felt able to pursue an extra-curricular interest in performing. He thus joined the Footlights Society, where he would go on to meet and mingle with such talented undergraduates as John Cleese, Jo Kendall, David Hatch, Miriam Margolyes, Humphrey Barclay, Chris Stuart-Clark, Jonathan Lynn, Tony Hendra, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Bill Oddie, Graeme Garden, Graham Chapman and Eric Idle.

A number of things made him stand out from this particular crowd. The most obvious one was his height - he was about six-foot-five - followed closely by his looks - with his dark curly hair and big darting eyes, he appeared like a mixture of Harpo and Groucho Marx that had been shaken together inside a cigar tube. There was also the fact that, as a graduate student, he was two or three years older than most of his fellow performers, and so had a worldliness, as well as an unworldliness, that intimidated a few and intrigued many others.

Something that held him back for a while was his failure to become part of any of the little cliques that tended to form among Footlights members over the course of a couple of years. It was natural for certain undergraduate members to bond together because clusters of them came from the same colleges, studied in the same faculties and went to the same lectures and supervisions (indeed, it wasn't unusual for their early routines to arise organically from their shared desire to joke about or parody the academic subject they happened to be studying). Buffery, on the other hand, led the solitary and far less structured life of a doctoral student, researching his own individual thesis and seeing only his personal supervisor, and so circumstances consigned him for a time to the role of a misfit.

It was John Cleese who started to bring him into the (or at least one) inner circle. He simply knew that Buffery offered something different.

As Cleese would recall in his autobiography, So, Anyway...:

Of the rest of the cast, I thought that the most interesting chap was a psychology post-graduate student called Anthony Buffery who was doing research on the memory of baboons. He was very bright, and I managed to learn quite a lot of academic psychology from our chats. He couldn't act for toffee, but he did weird solo acts that were extraordinarily original, and that he always invented on his own. His appearance helped his eccentricity; he was very tall and strong and upright, with a long, very pale face, huge eyes and a permanently surprised expression. An example of his work: he did a mime of a javelin thrower at an ancient battle who takes a long time before he actually launches his javelin... and then has nothing else to contribute to the occasion. Variations on embarrassment played a large part in Anthony's humour.

When Cleese, in his third and final year, was playing a dominant role in shaping the annual revue that would end up being called A Clump Of Plinths, he made sure that Buffery was very much involved. One consequence of this was that Cleese gave him the key role of the defendant Arnold Fitch in the most accomplished piece of writing of his career so far, a sketch entitled 'Judge Not':

BARRISTER: You are Arnold Fitch, alias 'Arnold Fitch'?

DEFENDANT: Yes.

BARRISTER: Why is your alias the same as your real name?

DEFENDANT: Because, when I do use my alias, no one would expect it to be the same as my real name.

BARRISTER: You are a company director?

DEFENDANT: Of course.

BARRISTER: Did you throw the watering can?

DEFENDANT: No.

BARRISTER: I suggest that you threw the watering can.

DEFENDANT: I did not.

BARRISTER: I put it to you that you threw the watering can.

DEFENDANT: I didn't!

BARRISTER: I submit that you threw the watering can!

DEFENDANT: No!

BARRISTER: Did you or did you not throw the watering can?

DEFENDANT: I did not!

BARRISTER: YES OR NO? DID YOU THROW THE WATERING CAN?

DEFENDANT: No!

BARRISTER: ANSWER THE QUESTION!

DEFENDANT: I-I didn't throw it!

BARRISTER: So - he denies it! Very well - would you be surprised to hear that you'd thrown the watering can?

DEFENDANT: Yes.

BARRISTER: And do you deny not throwing the watering can?

DEFENDANT: Yes.

BARRISTER: HAH!

DEFENDANT: NO!

BARRISTER: Very well, Mr Fitch - would it be true to say that you were lying if you denied that it was false to affirm that it belied you to deny that it was untrue that you were lying?

DEFENDANT: Ulp...Er...

BARRISTER: You hesitate, Mr Fitch! An answer, please - the court is waiting.

DEFENDANT: Yes!

BARRISTER: What?

DEFENDANT: Yes!

[The barrister tries desperately to work out if this is the right or the wrong answer]

BARRISTER: No further questions, m'lud.

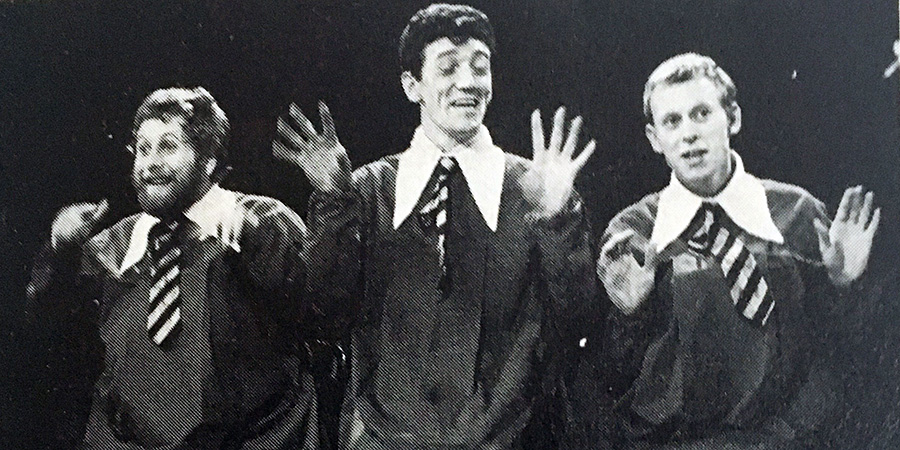

A Clump Of Plinths, which was performed in Cambridge in June of 1963, featured Cleese, Buffery, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Graham Chapman, David Hatch, Bill Oddie, Chris Stuart-Clark and Jo Kendall. A young impresario named Michael White saw the show and liked it enough to volunteer to stage it in London under the new title of Cambridge Circus.

Once the production reached the West End (not, somewhat confusingly, at Cambridge Circus but rather at the New Arts Theatre Club in Great Newport Street), all but one of the performers revised and developed their material in response to the general dictum: 'If they don't laugh, there's something wrong, and you've got to fix it'. The one non-conformist was Tony Buffery.

As Cleese would recall:

Just occasionally it's not quite as simple as [reacting to laughter], which is why I found Tony Buffery's solos so fascinating to watch. At one moment in the show we pretended something had gone wrong; there was an awkward pause, and then Tony would be pushed on to the stage and would stand there looking embarrassed and confused. He was wonderful at this, as he had an astonishing range of distressed expressions, intensified by his alarmingly pale complexion. He now explained to the audience that he had been asked to 'fill in' and that he would do so by performing some farmyard impressions. Then he did his impersonations of a cow, a cockerel and a sheep - and they were all absolutely awful. He apologised, but explained that those were the only ones he did. By this point the audience would be confused and uneasy. Tony now announced he would tell a joke. And he did. And again it was terrible. He apologised again, said he would try to do better and told another one - this time a fairly good one, and the audience laughed, partly out of relief. When they did, Tony jumped up and down with excitement and called to the wings, 'They laughed! They laughed!' Then he thanked them for laughing, and said that as they had liked the joke so much, he'd tell it again. So he told it again, exactly the same way. Silence. Tony looked crestfallen. He looked at the audience, paused, and then said, 'Please laugh'. I have never felt such discomfort in the theatre. Then Tony confided in the audience, 'Please laugh. My mother's in the audience tonight'. By now, some people were trying to hide under their seats. Tony scanned the balcony for some time, looking for his mother, and then smiled sadly and said, 'It's all right, she's gone now'.

Cleese thought it was 'wonderful', although he did later concede that it would take the rest of the cast quite a while to cheer up the audience after Buffery had vacated the stage.

It is not really known what the critics thought of Buffery, because, while Bill Oddie tended to be singled out as the most promising performer (one reviewer dubbed him 'a young Mickey Rooney' and another 'a comedian of uncommon ability'), most of the others, including Buffery, were usually mentioned only in passing. The Guardian did pause to describe him as 'an Eddison [sic] type,' which was not much help to anyone, but the others deigned not to dwell.

Cambridge Circus would eventually move on to a larger London theatre - the Lyric in Shaftesbury Avenue - before embarking on a tour of New Zealand and then a brief residency in New York. Buffery, however, would not go with it. He had decided, in Cleese's words, to resume 'his academic career with baboons,' and Graham Chapman was brought in as his replacement.

Buffery left Cambridge in the autumn of 1963 for the Psychology Department of the Montreal Neurological Institute in Canada, where he met with various specialists in his field, continued working on his thesis, and did some research for a couple of academic articles. His PhD dissertation (completed and examined the following year) would remain unpublished, but he had been given encouragement not only by Lawrence Weiskrantz but also the eminently well-connected Oliver Zangwill, Cambridge's Professor of Experimental Psychology (and the founder of British neuropsychology), to start applying for junior research posts back at his alma mater.

The result was that Buffery returned to Cambridge in September 1964, after just over a year in Canada, to sit his viva voce and then take up a three-year Research Fellowship at Corpus Christi College. His post involved the option of a little teaching, but was primarily a means of establishing himself as a notable new contributor to his specialist subject.

Rather than turn away entirely from his old extra-curricular activities, however, he threw himself straight back into the Footlights. He soon struck up a new friendship there with an Australian mature student named Clive James.

The twenty-five-year-old James had recently started his undergraduate studies in English, but was keen to make a mark as a performer (and just about everything else) as well. The stories about Buffery's past comic triumphs (and courageous failures) were still buzzing back and forth among senior Footlights members most evenings in their clubhouse (secreted conveniently in Falcon Yard, behind Petty Cury, near the town centre) - and the fact that he had turned his back on such a promising pathway into show business only added to the myth that had arisen in his absence. When, therefore, the man himself suddenly reappeared for the regular 'Smokers' (informal revues) at the cosy little ADC Theatre in Jesus Lane, James could not resist seeking him out ('He couldn't have been more approachable, so I approached him').

Chatting away to this inquisitively squinting Antipodean (one of the first things he did was to ask James what precisely he objected to about podeans), Buffery reminisced for a while about the old days with Cleese and Co, and explained why he had never felt driven by the same kind of ambition - 'I never finished anything. Lacked discipline. Still do' - and then, in a rather casual manner, suggested collaborating on some new material. James already had the outline of a routine about the Olympics folded up in his jacket pocket, so Buffery proposed adding to it by playing a succession of athletes, improvising visually as a mock-BBC commentary covered the event.

Standing in the shadows and providing the words, James was immediately dazzled by his partner's performance:

Buffery kept crossing the stage in various personae. He was the German Superman Hans-Heinz Reichstagger. He was the Russian female javelin thrower Olga Stickintinskaya. He was Tomkins, the perennial British loser with the pulled hamstring who might have done so much better. Hidden in the wings, I sometimes lost my place in the script, so entranced was I by the way Buffery became these people. Without leaving the ground, or not by much, he could mime Reichstagger doing a sixteen-foot pole vault, clicking his heels in mid-air as if he had suddenly met a superior officer.

The pair would go on to write and work fairly regularly together over the course of the next few years, not only contributing to Footlights productions but also, rather bravely, appearing at a couple of boozy May Ball college cabarets. Buffery was something of a mentor to James during this period, advising him on everything from how to direct to when (after awkward gigs) to take the money and run, but he was also enjoying the feeling of treading the boards again. In terms of comic creativity, his confidence was returning.

The sight of Buffery back in action certainly excited those who had known him in earlier times, and when his fellow Cambridge graduates Graeme Garden, Jonathan Lynn, Bill Oddie and Tim Brooke-Taylor were recruited alongside the old Oxonians Michael Palin and Terry Jones to write and appear in a new BBC comedy and music show called Twice A Fortnight (21st October - 23rd December 1967), they were quick to bring in Buffery as a regular performer.

It was a bitter-sweet experience for him. On the one hand, suddenly finding himself, at the age of twenty-eight, finally on national television, right in the middle of 1960s pop culture (the likes of The Who, The Moody Blues, The Scaffold, Small Faces, Cat Stevens and Cream were among the musical guests), was an enjoyably surreal moment, working with his comic peers again on another eye-catchingly irreverent show.

On the other hand, he was quite a caged creature comedically, obliged to fit into other writers' sketches (which were often filmed, quite hurriedly, by the director Tony Palmer) and never really given the opportunity to bring forth his full-blown 'Bufferyness' in any scene. Most of his physical humour and distinctive characterisations, and certainly all of his unnerving quirkiness, was missing as he was used mainly as a minor supporting figure.

When it was over, he went back to Cambridge feeling a little lost. His research fellowship now over, he was torn between waiting patiently for a senior position to become available (with all of the soul-destroying networking that, even in those days, was fast becoming obligatory) and looking elsewhere for academic work. In the meantime, he drifted for a while, doing independent research (at what was then the University's Unit for Research on Medical Applications of Psychology, situated inside a permanently chilly Victorian house quite some distance from the town centre - and the Footlights - on a street near the train station), trying the odd bit of teaching, and collaborating again with Clive James - which resulted, amongst other low-key things, with them staging a month-long two-man show at the Edinburgh Festival in the summer of 1968.

He left Cambridge soon after that to take up a position as a senior research officer at the University of Oxford's Human Development Research Unit. Even there, in a new place and at the start of a new decade, he still wasn't quite ready to shed the show business skin. He quickly became involved with the Oxford Experimental Theatre Group, and in 1970 ended up directing their latest revue, An Exhibition Of Ourselves, in Edinburgh that summer at the Festival Fringe. Contributing a routine of his own - a dead-pan parody of a TV news bulletin - he was praised by one critic for his 'laudable prowess in comic timing'.

Once the run was over, however, Buffery finally withdrew back into academia and concentrated on his research and his growing number of administrative duties. He still mixed every now and again with the local groups of budding comic performers (and once even agreed to play the psychologist Hans Eysenck in a stage dramatisation of the Oz magazine obscenity trial), but such excursions were far less frequent than before.

Indeed, a sign of how distant from his old life he had become was the fact that his name (alongside those of many old and obscure variety performers) was now showing up in the long list that Equity, the actors' union, was posting regularly in the trade papers, urging its 'missing' members to come forward and claim the money they were due.

Having been married, divorced and married again, and with young children to support, Buffery now felt obliged to at least try to act more like a conventional adult. Immersing himself in his work, he produced important insights into the possible differences between male and female brains, and how they might affect cognition, emotions and behaviour, and later on would help develop computer programs with a view to assisting recovery from strokes and brain injuries.

He chaired seminars. He attended conferences. He sat on committees. The comic sensibility was still in circulation, but now, most of the time, it was bubbling away from behind a carapace of scholarly sobriety.

He left Oxford in 1974 to join the Institute of Psychiatry at the University of London as a Senior Lecturer in Psychology. Many of the students he taught there would go on to be respected specialists in their own right, and would speak fondly of his fresh, fascinating, amusing and highly inspiring style of instruction.

That, however, would not quite be the end of Tony Buffery's performing career. He returned to the subject of comedy, and stood-up to do so, when, in July 1976, he agreed to give a paper at the International Conference on Humour and Laughter, which was held on that particular occasion in Cardiff.

Entitled 'Funny Ha-Ha or Funny Peculiar,' the paper was delivered in the same kind of daringly risk-laden style that had so impressed the likes of John Cleese about fifteen years or so previously. Complicating things immediately by discussing a condition called 'palilalia' but - for some unknown reason - referring to it as 'echolalia,' he began:

Professor Chairperson Junior, Doctors, M.A.s, B.A.s, Ladies and Gentlemen....B.Sc.s and Students.

Professor Chairperson Junior, Doctors, M.A.s, B.A.s, Ladies and Gentleman....B.Sc.s and Students.

Had the Convenors of this the International Conference on Humour and Laughter,

Had the Convenors of this the International Conference on Humour and Laughter,

Doctors Chapman and Foot,

Doctors Chapman and Foot,

realised that I suffer from a rare, nay unique,

realised that I suffer from a rare, nay unique,

speech disorder,

speech disorder,

I feel sure that they would not have invited me

I feel sure that they would not have invited me

to speak,

to speak,

but they didn't so they did so that's

but they didn't so they did so that's

that.

that.

My speech disorder is called

My speech disorder is called

Echolalia.

Echolalia.

I say things twice,

I say things twice,

or, if I shout,

or, if I shout,

thrice [shouted].

thrice [normal].

thrice [whispered].

Though listeners are all too aware of my speech disorder

Though listeners are all too aware of my speech disorder

I am not.

I am not.

People have told me about it

People have told me about it

but to no avail.

but to no avail.

My formal address will be boring enough

My formal address will be boring enough

and does not bear

and does not bear

repetition.

repetition.

Consequently, I'm afraid that you, my audience, are going to become very bored,

Consequently, I'm afraid that you, my audience, are going to become very bored,

all of you that is except for

all of you that is except for

my grandmother

my grandmother

who is unable to be with us this evening,

who is unable to be with us this evening,

and even if she could be with us is mercifully deaf

and even if she could be with us is mercifully deaf

and dead

and dead

and has been for the past twenty-nine years.

and has been for the past twenty-nine years.

Echolia is a congenital abnormality

Echolia is a congenital abnormality

found only in tall, curly-haired, male one-eyed neuropsychologists,

found only in tall, curly-haired, male one-eyed neuropsychologists,

so that lets me out [the Speaker removes the eye patch to reveal a second normal eye -

a long pause during which the Speaker looks much relieved - but...]

so that lets me out.

Who said that?

Who said that?

Me?

Me?

So much for miracle cures.

So much for miracle cures.

By the way, occasionally I do not repeat precisely what I have just said,

Sometimes I do not say exactly the same thing twice,

Though the meaning is more or less the same.

but the sense is similar.

This usually immediately precedes a cessation of echolia [there is a silence followed by another sigh of relief from the Speaker], but - it also usually immediately precedes some other form of speech disorder such as stammering or stutt... stutt... stutt... stutt... stuttering or even complete amnesia [the Speaker develops a dazed look and then a blank expression].

He then went on tell an anecdote ('A funny thing happened to me on the way to the conference...') about encountering a coypu, in a British Rail restaurant car, who was reading a copy of The Times. The coypu told him a bad joke and then jumped out the window without paying for its meal.

While recounting this tall tale, he checked his pulse, reacted with alarm when he supposedly couldn't find one, and then leapt up on to the table, rolled up his right trouser leg and revealed a pulsating knee-cap with a red heart painted on it, and then, visibly relieved, he climbed back down again and continued with his address.

He then announced that the main theme of his talk was actually 'Sex differences in the ontogeny and phylogeny of the neuropsychological development of verbal and non-verbal cathartic codes in solitary, dyadic and group interaction: towards a heuristic theory of client-centred merriment'. He attempted to 'illustrate' this via a sequence of slides (which, he claimed, included images of a German skier and his mother-in-law on holiday, but not in the same frame), which he presented by snapping his fingers and then pulling each 2x2-inch slide from out of his breast pocket, holding it up to the light and squinting at it.

Finally, he concluded by noting that, as many of the previous academic speakers had discussed the idea of the 'transgression of taboo as a source of tension reduction and thence laughter,' he may as well provide a practical demonstration of such a process. With that, he produced a plastic bottle with a squirting spout, supposedly full of 'strongish' sulphuric acid, pretended to burn a hole in a newspaper with it, and then squirted the 'acid' over the front row of his audience, letting them run around and scream before assuring them it was only tap water.

'Each of you,' he went on to say, 'now has a smile on your face because you think that I did not transgress the taboo of wiping a smile off your face by wiping off your face. My audiences usually think like that, they desperately need to believe that tragedy is comedy, that death is life, that acid is water - well, it was in fact acid, but I'm probably lying...probably, so I will not say anything else - except don't leave anything behind in the auditorium...particularly fingers, and be sure to count your ears before you go to bed'.

That was more or less it. After promising to leave his audience with 'this thought' - which was conveyed via a very long and pensive stare - he rolled up his left trouser leg to reveal the death card on his knee cap, shot a look of terror, and hobbled off while muttering to himself.

The audience was left to debate whether this had all been 'funny ha-ha' or 'funny peculiar,' which of course had been Buffery's intention (being an academic playing at being an academic whilst mocking academia from an academic standpoint), and it was certainly proof that he had grown even more of a comic maverick over his many years in semi-hibernation. It is hard to imagine any professional comedian of the time attempting something quite as audacious at a regular venue on the circuit, let alone in an international academic environment.

Andy Kaufman was taking similar risks in American clubs at the time - actually, Buffery had been doing something similar in British clubs long before Kaufman had even started - and, if Buffery had now been seriously inclined to resume his comedy career on a full-time basis, his best chance would arguably have been as the British equivalent of Andy Kaufman (with all of the controversy, confusion and chronic financial precariousness that such a role would have engendered).

That conference performance, however, would mark the end of Tony Buffery's on-off relationship with comedy - at least in terms of public appearances. He continued working in London for what was left of the 1970s, and then, during the next couple of decades, he moved on first to the University of Melbourne and then to hospitals and clinics in the U.S. (until, after leaving his post at New England Rehabilitation Hospital under something of a cloud after clashing with colleagues over their conservatism, he allowed his psychologist's licence to lapse).

Early in the current century, following several bouts of ill health and another divorce (his third), Buffery met a woman named Maria Kowalska in New York, and they married in 2006. Having trained to teach English as a foreign language, he moved with her to her homeland of Poland, where he spent the last years of his life, quite contentedly, and continued to make those who knew him laugh long and loud in strange and interesting ways.

Tony Buffery died on Boxing Day, 26th December, 2015. He was seventy-six.

He was not the Syd Barrett of British satire nor the Stu Sutcliffe of the Pythons, nor, ipso facto, Tony the half a bee. He was an internationally respected neuropsychologist, he was a naturally and prodigiously funny person, he was an individualist, he was a free spirit, he was sui generis, he was his own, his very own, A.W. H. Buffery, PhD (Cantab) Footlights (Hons).

He never missed out on anything. It was just the rest of us who missed out on him.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

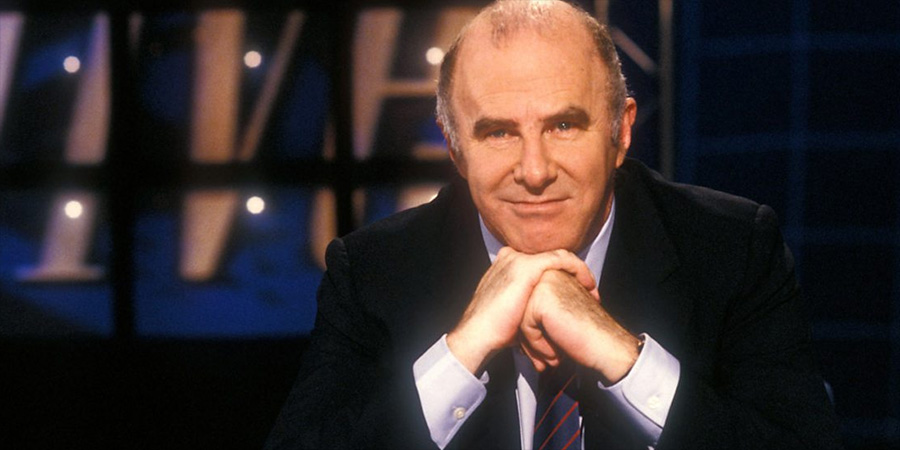

Love comedy? Find out moreJohn Cleese - So, Anyway...

Candid and brilliantly funny, this is the story of how a tall, shy youth from Weston-super-Mare went on to become a self-confessed legend. En route, John Cleese describes his nerve-racking first public appearance, at St Peter's Preparatory School at the age of eight and five-sixths; his endlessly peripatetic home life with parents who seemed incapable of staying in any house for longer than six months; his first experiences in the world of work as a teacher who knew next to nothing about the subjects he was expected to teach; his hamster-owning days at Cambridge; and his first encounter with the man who would be his writing partner for over two decades, Graham Chapman. And so on to his dizzying ascent via scriptwriting for Peter Sellers, David Frost, Marty Feldman and others to the heights of Monty Python.

Punctuated from time to time with John Cleese's thoughts on topics as diverse as the nature of comedy, the relative merits of cricket and waterskiing, and the importance of knowing the dates of all the kings and queens of England, this is a masterly performance by a comedy star.

First released: Thursday 9th October 2014

- Publisher: Random House

- Pages: 400

- Catalogue: 1847946968

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 4th June 2015

- Publisher: Arrow Books

- Pages: 432

- Catalogue: 9780099580089

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Cornerstone Media

- Download: 23.35mb

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Thursday 10th November 2016

- Distributor: Random House

- Minutes: 816

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Thursday 24th November 2016

- Distributor: Random House

- Discs: 12

- Catalogue: 9781846574153

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.