The Tales of Hoffnung: The Unscripted Genius of Gerard Hoffnung

Cases of pure comic genius are rare enough without us forgetting or overlooking any of them, so it is particularly important that more people discover, and enjoy, Gerard Hoffnung's quite brilliant conversations with Charles Richardson. Recorded in the late 1950s, they sound today as fresh and as funny as ever, and represent some of the most inspired, audacious and influential head-to-heads in British comedy history.

Hoffnung does not appear to be remembered by many these days, and of those who do still remember him, most of them do so more for either his unconventional musical activities, or for his laugh out loud 'Bricklayer's Lament' monologue, than for his collaborations with Richardson. The whole range of his work deserves reviving, however, because, at a time when true non-conformists seem so hard to find, the brief but bright career of Gerard Hoffnung is as refreshing as it is enlightening.

He was never a conventional character. He never led a conventional life.

Born in Grünewald, Berlin, in 1925, as Gerhardt Hoffnung, the only child of German-Jewish parents, his father fled to Israel in 1938 in the wake of the Nazi persecutions, while he and his mother escaped to England, where they rented a house in Hampstead Garden Suburb, which was to be Gerard's home for the rest of his life. It was here that, in a remarkably short space of time, he not only learnt the English language but also reached deep into the English psyche, re-emerging as someone who was still very much an outsider, but who could act and sound like an insider, and expose, at will, the intrinsic silliness of a narrow but notable range of native figures like no one else in the country.

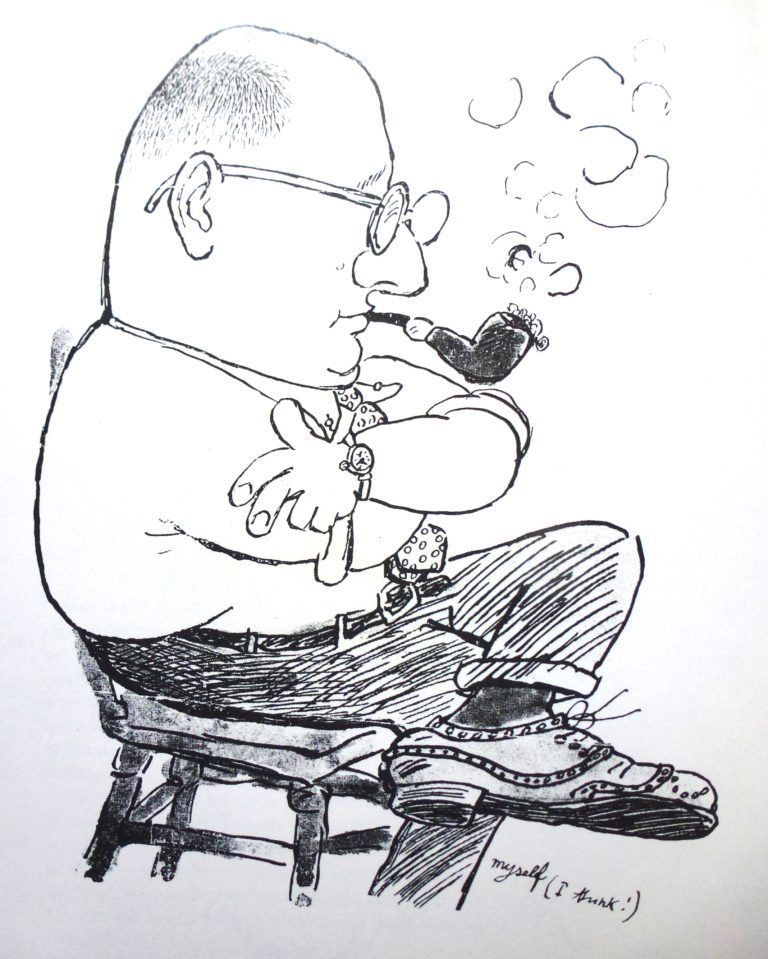

Stocky and prematurely balding with an inextinguishably benign outlook on life, he was likened by one admirer to a 'Teutonic Pickwick'. As if possessed by some wizened comic sprite, he looked, sounded and behaved so much like a far older man that his wife, Annetta, was sometimes mistaken for his daughter.

'He had so much humour in him,' she would later say. 'We used to travel by bus, and he would sit opposite me and he would try and make me laugh. I'd take no notice of him and then suddenly he would do a big twitch, or he could roll one of his eyes in a circle without the other one moving. And he would sit there looking terribly vacant while rolling this eye. And I'd try not to take any notice of him but he was so funny, and in the end I'd be laughing. But I wouldn't sit in front of him if I could possibly help it!'

A newspaper journalist who visited him early one morning at his home found him dressed smartly in a suit and tie and feasting on a breakfast that comprised of 'orange juice, grapefruit, cornflakes with cream and two chopped bananas, a boiled egg, four rounds of toast and butter, a small piece of smoked ham, a portion of liver sausage, three rolls and butter, chopped chives, Dutch cheese with radishes, pumpernickel bread and grapes,' rounded off with a pint of milk. He then started playing the tuba. The rather dazed reporter later emerged from the house with the gift of a hand-crafted pipe that Hoffnung had picked out from his extensive collection.

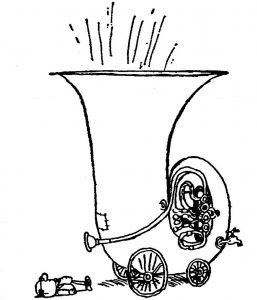

Hoffnung first made an impact as a cartoonist. Drawing mainly with a mapping pen and Indian ink, his clear and crisp comic images, which usually featured endearingly flawed-looking little human beings baffled in some or other way by mechanical objects, were published in the UK by the likes of Punch, The Strand Magazine and The Tatler, as well as numerous other newspapers and magazines in the US and countless other countries.

It was initially through his cartoons that he expressed his passion for music ('I love music to the point where it eats me'). In 1953 he published The Maestro, the first in a series of six books of comic illustrations on musical themes, which sold over 250,000 copies and further enhanced his fame.

Always driven by a desire to convert others to the magic of music - his wife once came home to find a rag-and-bone man's horse and cart tied up outside the house, and a somewhat bemused rag-and-bone man inside sitting on a couch while an excited Hoffnung, with a baton in his hand, hovered over him and 'conducted' a recording of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring - he used humour more and more to stifle any stuffiness. By the time that his third book - The Hoffnung Music Festival - was published in 1956, plans were well underway to translate his drawings into a full-length live concert ('a serious attempt,' as he put it, 'to combine music and humour').

After securing the Royal Festival Hall as a venue, Hoffnung commissioned six British composers to write new and suitably unconventional pieces for the event, promising that it would be 'a caricature symphony concert of immense proportions,' and 'an explosion of musical exuberance such as London has never heard before'. Tickets sold out in less than two hours (breaking all records for the Royal Festival Hall at that time), the BBC agreed to televise it, and the impact was impressive.

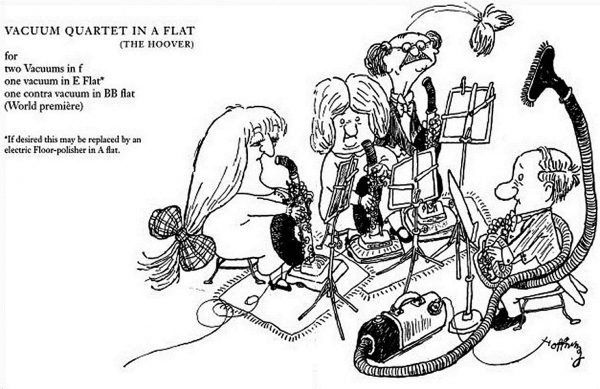

One of the most ear-catching compositions for the concert was Malcolm Arnold's Grand, Grand Overture - a piece scored for three vacuum cleaners (one upright in B Flat and a horizontal with detachable sucker in C), an electric floor polisher (in G), four rifles and a full orchestra. The score was dedicated, of course, to President Hoover.

Other highlights included the British virtuoso horn player Dennis Brain performing one movement of a concerto by Mozart's father on a mouthpiece, hosepipe and funnel, a Chopin mazurka re-arranged as a tuba quartet, and a fierce battle between an orchestra playing Tchaikowsky's Piano Concerto No 1 and a pianist persisting with Grieg's Piano Concerto. Not all of the reviewers enjoyed it ('I have heard less horrible grunting on a farm' moaned one classical critic), but most did. 'Its overwhelming success,' wrote one about the festival as a whole, 'does suggest that our present-day musical public is eager for a chance to laugh at its own foibles,' while another remarked that they would 'not readily forget the sight and sound of a huge audience rocking (if not rolling) with laughter in that most solemn (normally) of venues - a concert hall'.

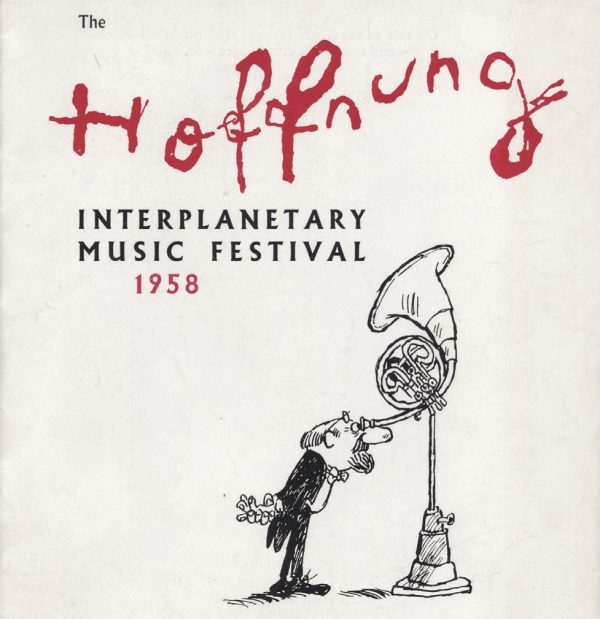

A second, similarly celebrated, event - the Hoffnung Interplanetary Music Festival - followed in 1958, and a growing number of composers and performers were drawn to the cause. Tours and broadcasts were planned, and further interest was shown from abroad, where he was applauded by music critics for his fusion of art, wit and populism.

Apart from cartoons and music, however, he was also making his mark as a distinctive, unpredictable and engagingly witty broadcaster. Beginning in January 1950 with a short talk on radio for the BBC's Home Service entitled 'My Intentions Were Serious: A Cartoonist's Problems,' he was soon in demand both for monologues and panel shows, and in 1951 became a regular on One Minute Please.

Devised and produced by Ian Messiter, One Minute Please was the more complicated forerunner of Just a Minute, and it proved perfect for Hoffnung's improvisational skills. Free to take wild flights of fancy in relation to a succession of random topics, his contributions were always engagingly eccentric, and rapidly won him a huge national audience.

Invitations soon followed from numerous institutions looking to make use of his skills as a witty and unpredictable social speaker, which saw him make several memorable appearances at both the Cambridge and Oxford Unions. He sometimes surprised audiences there with his seriousness - he was a Quaker and a regular prison visitor, with strong and sincere opinions about pacifism, social justice, sexual equality and the need to combat racial prejudice - but he always charmed them with his playful humour.

Alistair Sampson, who was President of the Oxford Union when Hoffnung was first invited to speak there in 1953, would later write of the visit:

Gerard came and gave one of the most superb comic oratoric performances that the Union can ever have heard. Devoid of cruelty and vulgarity, it was a superb example of pure humour. He was enchanting, fascinating and tumultuous. One moment he was offering snuff to his undergraduate audience, the next he was touching the microphone and leaping back as though electrocuted [...] So it is that others may remember him as musician, conversationalist or cartoonist, but I think of him as a speaker. He had all the graces for which those who analyse good speaking look - sympathy, observation, style and masses of audibility. He felt very deeply about many aspects of social and political life, but always at the back of his mind was the desire to keep the world sane with laughter.

It would be at one of his subsequent visits to Oxford, on 4 December 1958, that he was recorded giving a talk that included a tall tale about a bricklayer's letter to his employer recounting the multiple misfortunes endured while attempting what ought to have been a routine procedure:

Respected sir,

When I got to the top of the building, I found that the hurricane had knocked some bricks off the top. So I rigged up a beam, with a pulley, at the top of the building and hoisted up a couple of barrels full of bricks.

When I had fixed the building, there was a lot of bricks left over.I hoisted the barrel back up again and secured the line at the bottom, and then went up and filled the barrel with extra bricks.

Then, I went to the bottom and cast off the line.Unfortunately, the barrel of bricks was heavier than I was, and before I knew what was happening the barrel started down, jerking me off the ground.

I decided to hang on.

And halfway up, I met the barrel coming down, and received a severe blow on the shoulder.

I then continued to the top, banging my head against the beam and getting my fingers jammed in the pulley.

When the barrel hit the ground, it burst at its bottom, allowing all the bricks to spill out.

I was now heavier than the barrel, and so started down again at high speed.

Halfway down, I met the barrel coming up, and received severe injury to my shins.

When I hit the ground I landed on the bricks, getting several painful cuts from the sharp edges.

At this point I must have lost my presence of mind, because I let go of the line.

The barrel then came down, giving me another very heavy blow on the head, and putting me in hospital.

I respectfully request sick leave.

The hugely positive reaction this anecdote elicited, both on the night and in a subsequent broadcast on the BBC, has made it probably his most widely-known and warmly celebrated comic achievement, but that is not quite fair. It was indeed a brilliantly-delivered performance - potentially quite flat on paper, but rendered by his reading into something akin to a musical composition, subtly evolving its rhythms and intonations as it rose to a crescendo - but it was also by far his most contrived.

He claimed at the time that he had read the letter in a recent issue of the weekly bulletin of The Federation of Civil Engineering Contractors. The truth was that the story originated back in the 1930s, as a letter that had been received by a government agency. It had first appeared in print in an edition of Reader's Digest in 1940, recording a missive supposedly sent by an enlisted seaman to his naval officer explaining his late return from leave.

Hoffnung had first seen the piece as a light-hearted 'miscellany' entry in The Manchester Guardian on 11 June 1957 - six months before his Oxford Union appearance. This version was - word for word - the same one that he would go on to use himself, except that he changed the location of the bricklayer from Barbados to Golders Green for ease of understanding.

He then proceeded to polish his performance of it (a cartoonist bringing a cartoon-like incident to life) while working as a panellist on One Minute Please at the BBC. As his producer, Ian Messiter, would later explain: 'I was just about to do the warm-up, and he said, "Oh, Ian, I wonder if I can do the warm-up for you? I want to read to them from out of the papers". I said, "Well, that's not a very good idea for a warm-up, but I guess anything's better than mine, so off you go". And he went out on the stage and he read a most extraordinary letter'. It was about the bricklayer. 'Well, he read this story every single week that we were doing One Minute Please. So that by the time he'd read it about, oh, six or eight goes, he'd got it pretty well perfect'.

That Oxford performance, therefore, was very unusual for Hoffnung, because, as inspired a performer as he always was, his real genius was rooted not in such scripted and pre-rehearsed routines, but rather in the entirely spontaneous interactions he would enjoy with his fellow broadcaster Charles Richardson.

Richardson was a Canadian actor who also worked in radio, and, during his time in Britain at the BBC, presented a number of programmes - including, from 1958, a 'mixed bag' sort of show (described at the time as 'a three hour miscellany designed to meet the needs of an audience most of whom would not be listening continuously') for the Light Programme called Saturday Night on the Light. Hoffnung was recruited to contribute a few minutes of light-hearted chat each week, with Richardson acting as a mock-serious interviewer.

They made for an excellent comic contrast: Richardson, with his slick, sober and precise style of speaking, sounded neat, proper and buttoned-down, probably with brilliantined hair and a plain bowtie; Hoffnung, with his reedy, wheezy-sounding voice, sounded - although he was still only thirty-three at the time - like an elderly member of the country's ruling class who had just emerged from his gentlemen's club, splattered in soup stains, after a long and well-lubricated lunch.

What followed, right from the start, was a kind of artful deconstruction of the conventional interview format, with Richardson trying to stick doggedly to his brief while Hoffnung sat back and supplied a textbook demonstration of how to reduce such a conversation to a shambles by (a) not listening carefully, if at all, to most of the questions; (b) interrupting repeatedly with completely unrelated information or observations; (c) causing confusion by treating serious things as trivial and taking trivial things very seriously; and (d) suddenly taking offence for no coherent reason.

Their first - as always completely unscripted - exchange stayed relatively civil, but it still hinted, towards the end, at the conflict that was to come:

RICHARDSON: Mr Hoffnung, ever since I first met you, there's one question I've been desperately wanting to ask you. I hope it won't embarrass you, but could you tell me something about-

HOFFNUNG: No, just ask me about anything you like.

RICHARDSON: Well, could you tell me something about your childhood?

HOFFNUNG: Yes. Yes, certainly. What do you want to know?

RICHARDSON: Well, just, if you would start at the beginning...

HOFFNUNG: Well...I was born at a very early age...As a matter of fact I was two when I was born. I remember that. Very well.

RICHARDSON: Did you play any instrument at that early age?

HOFFNUNG: Yes. I played practically all instruments in the orchestra, when I was about that age. But, believe it or not, I was a very ugly child. When I was small. Very ugly. Hideous. The, er, only nice thing about me was my hair. I had a head of the most beautiful curly golden hair. As a matter of fact it used to go - it was so long, my hair, that it used to trail behind me in the dust. As a matter of fact, my hair grows inwards now. And it comes out on my chin every morning, and I shave it off. If you really want to know.

RICHARDSON: Well, what I really wanted to-

HOFFNUNG: That was what you wanted to know, wasn't it?

RICHARDSON: Well, no, it wasn't exactly. I was wondering, if your musical education was complete at the age of two, what happened after that in your childhood?

HOFFNUNG: Yes. Oh yes. Certainly.

RICHARDSON: (Confused) Y-You mean...things did happen?

HOFFNUNG: Yes. Oh yes. I, er, certainly, yes. I grew up. I grew up. I went to school.

RICHARDSON: And at what age did you decide to follow the career which you subsequently did?

HOFFNUNG: Oh, I, er, I decided that long before I ever went to school. I decided to become an artist. I'm an artist, you know.

RICHARDSON: More than a musician?

HOFFNUNG: Oh yes. Oh yes. I, er, my musical friends, they think I'm a very good artist. And my painter friends, they think I'm a very good musician.

RICHARDSON: When did you switch from art to music?

HOFFNUNG: Oh, I switch all the time. I, er, sometimes, I used to do a bit of both - ha ha ha! -

RICHARDSON: You mean at the same time?

HOFFNUNG: Oh yes, yes, yes! Not at the same time, no, don't be silly!

RICHARDSON: You can't draw while playing a tuba?

HOFFNUNG: No, no! How can you do things like that? That would be impossible!

RICHARDSON: Well, you're a remarkable man, Mr Hoffnung.

HOFFNUNG: It's not possible. No, no! Nobody, ah...I rather resent you saying that to me. I, er, nobody could possibly do that together!

RICHARDSON: Well, it's just because you said you did do them together, you see, that's why I mentioned -

HOFFNUNG: No! I didn't mean, ah - that's absurd!

RICHARDSON: Well, I'm sorry if I upset you.

HOFFNUNG: (Softly, sounding hurt) No, no, no. I think you shouldn't have said that, you know. I don't think you should have said that.

RICHARDSON: I'm very sorry. What you mean is, you play the tuba for a couple of hours, and then you put it down, and then you perhaps draw for a couple of hours?

HOFFNUNG: (Very softly, sounding very hurt) I think you should think your questions over more carefully.

RICHARDSON: Yes, well, you did give me a bad lead there, you said that you did-

HOFFNUNG: No, I didn't! I didn't! You gave me a bad lead! I don't think you should have said...I think you should, er...well, I hope that you're sorry. 'Two things the same way'!

The thing that made these dialogues not just delightfully silly but also consistently engaging was the fact that both men played it so 'straight' and thus kept the comedy characterful. Richardson, in his nasal, nagging way, never stopped sounding as if he really, really, wanted to understand what on earth Hoffnung was wittering on about, and Hoffnung never stopped sounding as if he genuinely was this bizarre old solipsistic eccentric.

The key moment that sets the tone for the entire series is when Hoffnung utters that ludicrously aggrieved, aggressive, absurdly accusatory line, 'If you really want to know': he was the one who volunteered the information, and then elaborated on it, but then is reacting as though it was dragged out of him by an impudently intrusive interviewer - and yet he says it in such a strangely natural-sounding manner. It is impressive not just as improvisation but also as acting, and that is what makes these sessions so special.

The subsequent conversations would grow increasingly surreal, irrationally combative and sometimes hilariously incoherent, oscillating between awkward public inquisitions and quasi-marital spats, with Hoffnung sounding as though he was drifting in and out of a dream and Richardson, on many occasions, as though he was finding it harder and harder to resist the temptation to knock the other man flat out with his fist:

RICHARDSON: What have you been doing since I last-

HOFFNUNG: I remember the last time I saw you, you were coughing and spluttering away like an old drain.

RICHARDSON: Yes, well, you probably said something to embarrass me.

HOFFNUNG: You looked really down and out, you did, my dear fellow.

RICHARDSON: Did I?

HOFFNUNG: Really down and out.

RICHARDSON: You probably embarrassed me.

HOFFNUNG: Did I? Oh, no, I wouldn't want to do that!

RICHARDSON: Yes, that's probably what happened.

HOFFNUNG: Oh. Well, I'm sorry, I do apologise.

RICHARDSON: (Determined to move on) What do you think of this weather?

HOFFNUNG: I don't like to embarrass you ever, Charles. I may call you Charles, may I?

RICHARDSON: Yes, indeed. What do you think of this weather?

HOFFNUNG: Because we've known each other for so long now.

RICHARDSON: (Sounding impatient) Yes, we have. Well, we must talk about something. Could we start with the weather? Do you like the weather?

HOFFNUNG: ...What can I do for you?

RICHARDSON: (Getting even tetchier) Well, I just wondered if we could start talking about the weather!

HOFFNUNG: The WEATHER???

RICHARDSON: Yes! Do you enjoy this rainy weather that we've had?

HOFFNUNG: No, no, no. Of course I don't. Do you? Do you like the rainy weather?

RICHARDSON: I don't mind it, I don't mind it. I'm inside most of the time.

HOFFNUNG: That's why you got that cold last time. That's why you were coughing and spluttering away....

RICHARDSON: Are you inside most of the time?

HOFFNUNG:...with that drrrripping nose. And drrrripping eyes, with rrrred rrrims.

RICHARDSON: I'm going to keep saying this until you answer!!!

Other topics covered included cinema; smokeless pipes; cricket; hunting humans who hunt animals; cocoa; haircuts; monkeys on the moon; broadcasting in colour; dieting; dreams; and a gloriously bad-tempered non-discussion of travel. One of the best of all, for its mixture of whimsy and simmering irritation, wandered its way to a strange winter's tale:

RICHARDSON: Mr Hoffnung, you always appear to me to be particularly immaculate all the time.

HOFFNUNG: 'Immaculate'? I don't look immaculate! I always look very clean and neat! I don't know how you can say that!

RICHARDSON: Well, that's what I mean, you see, by 'immaculate'.

HOFFNUNG: No! You said I looked 'immaculate'. That doesn't mean clean and neat!

RICHARDSON: Er, well, I've always thought it did.

HOFFNUNG: I look very tidy. I take a special pride with my appearance.

RICHARDSON: But-But 'immaculate'- that's just what that means, Mr Hoffnung!

HOFFNUNG: (Quietly) No, it's all right, no, no, so long as if we just leave it at that I'll be quite satisfied. Okay?

RICHARDSON: Er, all right, all right, I, er, what I was leading up to was-

HOFFNUNG: (Sounding hurt) I can't understand you, because I've always taken a particular pride in my appearance.

RICHARDSON: Yes, well, that-that's what - we agree on that basic point. Which made me wonder, are you married, or...who looks after you?

HOFFNUNG: It's none of your business whether I'm married...Of course I'm married!

RICHARDSON: Oh...Oh, well, it was just a...thought.

HOFFNUNG: I don't like these sorts of questions.

RICHARDSON: Do-Do you prefer being married?

HOFFNUNG: (Testily) Yes, yes! Yes, I'm very happy, thank you very much! I'm very happily married!

RICHARDSON: Um...

HOFFNUNG: I wasn't always married.

RICHARDSON: No? Not when you were young?

HOFFNUNG: No, no.

RICHARDSON: What, er, what did-

HOFFNUNG: I used to have a housekeeper to look after me.

RICHARDSON: (Sounding more interested) Oh, yes, I think I've heard of this, somebody told me, yes...she was a bit odd, wasn't she?

HOFFNUNG: No. No, no. She was very small, that was the only odd thing about her. I'll never forget the first day she came to me, I could see her through the window. She was jumping up at the bell. Trying to ring the bell. She was jumping up at it, she was so small.

RICHARDSON: Did she ring it?

HOFFNUNG: No! She couldn't - she was too small!

RICHARDSON: Has she ever...rung the bell?

HOFFNUNG: Yes. Of course she's rung the bell!

RICHARDSON: And she used to look after you?

HOFFNUNG: She used to look after me. She was, ah...Ha! I'll tell you what happened to her once. She was very fond of animals, you know? She woke up one night, I remember, it was about midnight, and in the moonlight she went to the front door and opened it up and there'd been a fresh fall of snow. It was winter, y'know?

RICHARDSON: Were you up too or did she-

HOFFNUNG: No, no. She told me this. I could hear her grovelling about in the house but I didn't know what it was. I just thought it was a burglar or something like that. So she opened the door, and in the snow, she saw a hedgehog. With all the prickles, y'know? Well, this hedgehog was sitting on her front doorstep - it was very cold, y'know, it was frozen - and she took pity on it. She went into the kitchen and she made some broth, some hot broth for it, and she went down, and she put it in a little saucer, poured some milk over, and left it there. She didn't want to pick it up because they're prickly, y'see?

RICHARDSON: Is this going to be a very long story?

HOFFNUNG: Yes.

RICHARDSON: Oh.

HOFFNUNG: So she went back to bed. And then - ha ha ha! - she woke up, because she couldn't sleep, y'see, she was so worried about it, and she went and had another look, and she went down and found that this animal was still there, and hadn't touched its broth, so she took it back in the kitchen and heated it up and sprinkled some breadcrumbs over it wanting to make it more attractive for the hedgehog.

RICHARDSON: (Sounding almost past caring) She told you all about this the next day?

HOFFNUNG: She did. Oh yes.

RICHARDSON: She always told you these things she was doing in the night, did she?

HOFFNUNG: Yes, yes. Sometimes she used to tell me the day before. But usually she used to tell me the day after.

RICHARDSON: How could she tell you the day before?

HOFFNUNG: Look: LET ME JUST GET ON! So she, er, she... What was I saying? Oh yes. This little thing was still sitting there, so she just put the broth in front of the animal and she went back to bed. And the next morning, when she came down, she found that not only had the snow melted completely, my dear fellow, but the hedgehog turned out to be a lavatory brush which she'd left there the previous day to dry.

RICHARDSON: Really?

HOFFNUNG: Really.

RICHARDSON: That's a true story?

HOFFNUNG: Absolutely true.

RICHARDSON: Well, I think it was immaculately told, I must say, immaculately told.

HOFFNUNG: Oh, yes, it certainly was, yes.

RICHARDSON: Thank you.

There probably would have been far more of these conversations but for the tragic fact that Gerard Hoffnung suddenly collapsed and died from a cerebral haemorrhage, at the age of just thirty-four, on 28th September 1959. Among the countless tributes, The Times probably put it best when, in reference to his multifarious achievements, it said: 'It is usual to say that a man has left behind a gap that cannot be filled. For Gerard Hoffnung there would be needed a handful of men, all of them greatly gifted'.

His work, however, would continue to inspire many of those who remembered him, or had newly discovered him, during the decades that followed. His artistic and musical adventures were celebrated in a succession of exhibitions, festivals and concerts (as well in such significant compositions as The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band's 1967 The Intro & The Outro), while the surviving recordings of his comedy performances were reissued on several occasions.

This meant that one can still recognise echoes of his much-loved 'The Bricklayer's Lament' in subsequent comic routines, such as Jasper Carrott's 'Insurance Claims'. One can also, more broadly, appreciate the enduring impact of his conversations with Charles Richardson in the work some of the most accomplished comic stylists who followed him.

One sketch, for instance, that is so Hoffnung-esque it is practically an homage, is John Cleese and Graham Chapman's wonderful Monty Python piece in which the eminent composer Arthur 'Two Sheds' Jackson becomes progressively rattled while being asked about the fact that he is known as 'Two Sheds':

HOST: 'Two Sheds'. How did you come by it?

JACKSON: Well, I don't use it myself, it's just a few of my friends call me 'Two Sheds'.

HOST: I see. And do you in fact have two sheds?

JACKSON: No, no, I've only one shed. I've had one for some time, but a few years ago I said I was thinking of getting another one, and since then some people have called me 'Two Sheds'.

HOST: In spite of the fact that you have only one?

JACKSON: Yes.

HOST: I see. And are you thinking of purchasing a second shed?

JACKSON: (impatient) No!

HOST: ...To bring you in line with your epithet?

JACKSON: NO!!

HOST: I see, I see. Well, let's return to your symphony. Did you write this symphony in the shed?

JACKSON: No!

HOST: Have you written any of your recent works in this shed of yours?

JACKSON: No, no! It's just a perfectly ordinary garden shed!

HOST: I see, I see. And you're thinking of buying this second shed to write in?

JACKSON: No, no. Look. This shed business - it doesn't really matter at all! The sheds aren't important! It's just a few friends call me 'Two Sheds' and that's all there is to it! I wish you'd ask me about my music. I'm a composer! People are always asking about the sheds, but they've got it out of proportion! I'm fed up with the shed - I wish I'd never got it in the first place!

One can also discern traces of Hoffnung in some of Peter Cook's writing and performances, from E. L. Wisty and the Not Only... But Also... Pete and Dud dialogues through to the Derek and Clive exchanges (such as 'The Worst Job I Ever Had,' 'Squatter and the Ant' and 'I Saw this Bloke'), as well as the conversations between his Sir Arthur Streeb-Greebling and Chris Morris in the Charles Richardson role which were broadcast under the banner of Why Bother?.

In fact - if you really want to know - once you've heard Hoffnung himself, you can even hear him in all kinds of far more recent British comedy. Once you do that, you will cherish the memory of this remarkable man even more.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more