Hark at the other Barker: The many achievements of Eric Barker

The notion that appearances can be deceptive certainly rings true in the case of Eric Barker. He is best-remembered these days for his roles in countless British film comedies from the middle of the 20th-century, including several of the Carry Ons, usually portraying peevish little officials forever tut-tutting at the chaos and incompetence all around them. That, however, is merely the tip of the iceberg, or the brim of the Barker, as far as this fascinatingly multi-faceted man is concerned.

He did much more than movies. From the 1930s to the 1950s, before becoming a near-ubiquitous presence in British cinema, he was a stand-up comedian, a radio star, a critically-admired novelist, a poet, a playwright and director. To properly appreciate him, then, we need to reveal what's since been hidden and take in the totality of his talent.

Born in Thornton Heath, London, on 20th February 1912, the youngest of three children (two boys and a girl), Eric Barker was brought up in Croydon, Surrey, in considerable comfort (the family were tended to by several servants), and educated locally (and miserably, he would later say) at the independent Whitgift School. Writing was something that rapidly became a passion, and, although his first full-time job (at the age of sixteen) was at his father's paper merchants' company in the City (Aylott & Barker, in Queen Victoria Street), he soon left in order to concentrate full-time on writing.

There followed many anxious months, typing away in a room in his parents' house, until, at last, he had a short story accepted in Twenty Story Magazine, paying him five guineas. After this breakthrough, he pushed on with greater conviction.

His first novel, a self-consciously PG Wodehouse-style comedy entitled Sea Breezes, came out in 1932, under a pseudonym, Christopher Bentley, because, he would later say, 'I was so ashamed of it' (even though his humour impressed Wodehouse himself sufficiently to see him later invited to contribute to one of the latter's edited collections). His second work, Day Gone By, a satire about suburbia, was published the following year under his own name, and received some excellent reviews ('It is many years', wrote one critic, 'since we have met a first novel of such amazing promise'), as did his third, The Watch Hunt (a comic school story, also published in 1933).

The mockery of authority was a theme that would run through these books, and, indeed, beyond them to much of what else he would create in terms of his style of comedy. He had hated most of his teachers at school, and would never warm to anyone else who abused their position of power. Right from the start, there was a satirical sharpness to his humour, a punch behind the playfulness, that niggled those who realised that they were among the targets of his taunts.

Novels were only one of many outlets in these early days for Barker's creative energy. He was also increasingly busy performing stand-up comedy (with topical impressions being a key ingredient), had short spells in rep at Oxford, Birmingham and Croydon, appeared in a succession of satirical revues, wrote several three-act plays (both dramas and comedies) as well as a number of songs, submitted poetry to various journals and magazines, and also worked as a lyricist for, amongst others, the composer Rex Burrows. He simply never stopped.

In 1933, his first agent, the magnificently grand Madame Cecilia Arcana (whose real name, before she dyed it, was Olive Clifton, and who was blessed, Barker would say, 'with an unalterable conviction that she knew more about the theatre than anybody else, living or dead'), arranged for him to be a resident comedian and sketch performer (for a fee of £4 per week) at the then-relatively new Windmill Theatre in Piccadilly. Appearing in ensemble shows called 'Revudeville', he was an instant success - 'One of Revudeville's greatest discoveries,' wrote one critic, 'is Eric Barker - [although] he may be a trifle over the heads of the average audience - his material is always so clever, and he puts it over in a very original way'.

The fact that some observers were indeed rather baffled by Barker's material never bothered him in the slightest. Although never arrogant, he possessed a strong sense of conviction as to what counted as high quality comedy - he was alert to the threat of cultural 'dumbing down' as far back as the Thirties - and was uncompromising in his outlook. As his boss at the Windmill, Vivian Van Damm, would later recall of this precocious performer, 'I soon learned that he didn't give a rap what the audience thought of him, and still less what I, as his employer, thought'.

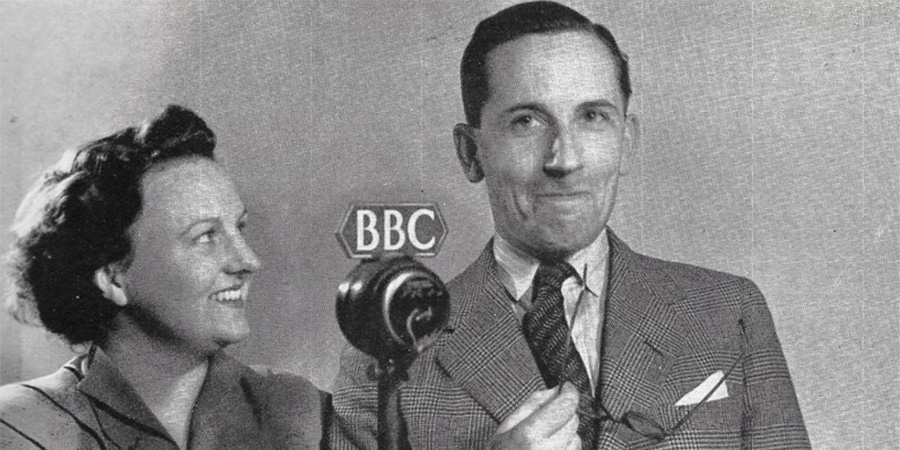

One of his fellow performers there was Pearl Hackney, a young dancer and comic actor who had come down from Liverpool in the hope of winning roles in the West End. They not only worked very well together on stage but became close friends off it as well, forming an informal partnership in which her ebullience and his shyness found a remarkably happy balance.

Their budding romance was interrupted when Barker's part of the revue troupe was hired for a lengthy engagement in Australia, spending ten weeks at the Tivoli Theatre in Melbourne followed by six weeks in Sydney. Once he was back in Britain, however, the relationship was resumed, and rapidly grew more serious.

They married in 1936, settling together for a short time in a small flat in Chelsea until they found an 'absolutely enchanting' long-term home at Hillside Cottage in the village of Stalisfield in Faversham, Kent. They would stay there for the rest of their lives, and their daughter, Petronella Barker (born in 1942), would grow up to be an actor in her own right.

Marriage, however, did nothing to slow the progress of either performer's professional career. Both Eric and Pearl - often working together - continued to take on whatever challenges came their way.

One of the ones that arrived first for Eric saw him bid to make a name for himself in radio. The story of how he made his entrance into the medium, however, tells one rather more about the whimsical workings of the BBC in those days than it does about the quality of his comic performances.

It happened in 1933, when he went for an audition at the BBC, which took place in a studio on the tenth floor of the newly-built Broadcasting House, in the presence of Eric Maschwitz - playwright, songsmith, sybarite and, at that time, the BBC's Head of Variety. 'Radio is the future', Barker's agent Madame Arcana had told him. 'You need to get yourself in there quickly.'

Suitably motivated, Barker performed a routine there that he was currently performing at the Windmill. It featured, amongst other things, a few impersonations of various public figures of the time, including the Labour Party leader and Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. When he had finished, Maschwitz sat back and said, 'Hmm... yes, that's very nice, but you must have something suitable for broadcasting'.

Barker nodded obediently, but actually was completely baffled. 'I didn't know what he was talking about at all'.

Once he was back home, he sat and pondered what 'suitable for broadcasting' could mean. What Maschwitz probably meant, given that the BBC was always chary about being seen (or heard) to be irreverent about public figures (although a formal ban on that practice would not come until the publication of its notorious set of guidelines, known as The Green Book, in 1949), was that the routine needed to lose the political impersonations - but, then again, Maschwitz was a mercurial character and he might simply have been seeking a standard of script that struck him as slightly superior. Barker, however, remained none the wiser.

A fortnight later, Cecilia Arcana called him with the news that she had arranged for him to appear on First Time Here, a teatime show the BBC used to try out new untested talents. 'But I haven't got anything written', he exclaimed. 'They want something "suitable for broadcasting" and I still haven't worked out what that means!' Arcana ordered him to calm him down: 'Don't worry, dear,' she said, 'just go along and do what you did last time'. He remained in a state of anxiety - 'I can't!' he said, 'Eric Maschwitz didn't like it!' - but the formidable agent insisted: 'Do as I say!'

He did continue to worry, but he did what she said and went back to the BBC with exactly the same script as last time held tightly in his hands. This time he found himself in a different studio, with - much to Barker's relief - a different figure observing from behind the glass. As Barker started the repeat performance, however, he was shaken to spy a second presence, lurking behind his fellow producer, partly hidden in the shadows. It was, he soon realised, none other than Eric Maschwitz. 'Well, that's torn it', he thought to himself. 'That's the end of that!'

When the show had finished, however, Maschwitz stepped out of the darkness, came out to meet Barker and shook him warmly by the hand. 'Thank you very much, that sort of material is ideal for radio,' he declared. 'If you can turn out stuff like that for us we'll be able to use you often!' Barker was again left bemused, but also, this time around, very happy. He was now in radio.

What he went on to do in radio, from this time up to the start of the Second World War, remains something of a mystery, beyond the basic listings, because all of the recordings, along with his artist's file, were among those items destroyed during the Blitz. What we do know is that, in 1934, he appeared in a series called The Chariot Hour, followed by, among many other things, a spell as compère of a show entitled Dance Cabaret, and his own operetta in 1939 called His Majesty's Pleasure.

Once war intervened, he continued to be a radio regular. Although in 1940 he volunteered to serve in the Royal Navy, he was recognised immediately by officers as 'that bloke on the wireless', and was put to better use as an entertainer in forces broadcasts.

He would go on to contribute to a show known as Howdy Folks (which sometimes ended with a question mark and sometimes an exclamation mark), followed later the same year by a series called Wait For It. He was also able to team up again with his wife Pearl when they co-starred in the 1943 series Three's A Crowd, and then the following year he became a regular in two more revue series for the forces, one called Navy Mixture and the other Mediterranean Merry-Go-Round (shortened the following year to Merry-Go-Round).

One of the distinctive features of Barker's input into these shows was the slyly iconoclastic quality of his monologues and sketches. Countless authority figures, and institutions, were roundly mocked by the comedian, with the BBC, the Government and the military forces all included among his many targets. Always instinctively resistant to rigid disciplinarians, as well as to the pompous and pretentious, he seized any opportunity he had to cut them down to size with comedy.

Merry-Go-Round, in particular, became a place where service men and women, along with the public at home, could tune in to hear some refreshingly irreverent takes on various current political and military affairs. A sort of sitcom with musical interruptions, set on H.M.S. Waterlogged at Sinking-in-the-Ooze, it would see Barker adopt an affected 'posh' accent and play the fussy but incompetent officer, issuing silly orders and generally failing to get much done while his underlings dozed off, dodged duties or went missing.

An example was this typical exchange between Barker and his wife, Pearl, playing their Navy characters, when, once again, they went 'off message' and reflected on their irrelevance:

PEARL: Look, Eric, I hate to say this, but I don't think you're cut out for the Navy. Now, please, don't let that make you too unhappy.

ERIC: Oh, that's all right, little woman, I can take it on the chin. I've had some pretty tough knocks in my time - but not cut out for the Navy?

PEARL: No.

ERIC: Blimey, I've been trying to sell that one to every M.O. I've met for the last five years! What have I ever got out of it? - a course of injections.

PEARL: What are you going to do when you leave the Navy, Eric?

ERIC: Oh, the same as when I've been in it.

PEARL: Don't be silly - you must do something!

By the later stages of the war, however, these mildly satirical routines about the senior service had reached the attention of the Admiralty, who were so displeased by Barker's irreverence that, in November 1945, they actually felt moved to send a spy to assess a situation they described as 'getting a bit strong'. The man they chose to be this spy, however, was a young lieutenant by the name of Jon Pertwee.

Pertwee proceeded to go native more or less immediately once in Barker's presence. Arriving at the Criterion Theatre, where the show was recorded, he sat in the darkness and watched the latest rehearsal with great interest until it stalled because the man who usually served as a 'plant' in the audience, shouting out questions on cue, had gone absent with a cold. Pertwee, who had greatly enjoyed what he had heard up to that point, could not resist stepping out of the shadows and volunteering to act as a stand-in.

'Who are you?' asked a puzzled Barker. 'Well, um, I'm a spy, actually,' Pertwee confessed. 'You're a SPY?' Barker replied. 'Yes,' said Pertwee, 'but let me do this and then I won't spy.'

Barker, recognising a kindred spirit, was happy enough to comply, and, sure enough, Pertwee did well enough for Barker to ask him to come back the following week. The erstwhile spy thus became a current member of the cast, playing several characters and establishing himself in the process as a promising radio performer in his own right, while continuing to learn invaluable lessons from his more experienced colleague.

The BBC, unlike the Admiralty, was sufficiently satisfied with all of Barker's efforts to award him an exclusive contract, guaranteeing him a steady income of twenty guineas per week while he continued to work in radio. He was, to put it mildly, an unusual employee with which to deal - he often corresponded with the Corporation's contracts department via rhyming couplets, or Shakespearean parodies, or knowingly verbose bursts of esoteric allusions which sometimes amused and sometimes bemused those who were obliged to reply - but such idiosyncrasies, in those days, were indulged by executives who rather liked the idea of having such quirky 'individualists' in their midst.

The show went on until 1948, when it metamorphosed into the peacetime sitcom Waterlogged Spa and continued more or less as before. This, to an extent, made sense, because the situation and its characters remained popular, even though Barker, as its writer, knew that there were only so many variations on the theme to keep rotating.

It did not take too long, however, before Michael Standing, the BBC's Head of Variety, started to circulate his opinion that Waterlogged Spa was sounding somewhat soggy, with 'the old magic' seeming to have 'temporarily deserted' its star. He had a point - the scripts were growing increasingly self-referential, with gags about old gags and comments about catchphrases - and Barker himself would later admit that he became 'so exhausted mentally I could not tell in the end if I was writing well or badly', but he was still disappointed when, in July 1949, he was informed that the Corporation had decided not to extend his contract.

He did make some guest appearances on radio in the months that followed, performing his own rambling brand of stand-up comedy (the style would later serve as one of the formative influences on Ronnie Corbett's better-known sit-down monologues), but he sailed rather close to the wind with material that joked about his changed relationship with the BBC and its bosses ('I don't care', went one of them. 'What does radio matter? I'm looking for a job with a future... The last series I did, Merry-Go-Round, you know, that ended on purely technical grounds. There was a strange noise the engineers couldn't account for until a doctor wrote in and said it was the arteries hardening...').

There were, nonetheless, still some people at the BBC who wanted to work with Barker, and late in 1950 one of them, Charles Maxwell, agreed to make a pilot of a new show he had proposed, called Just Fancy. The pilot was judged a flop - the subtlety of the humour, and the laidback nature of the approach, seemed to confuse some listeners more used to loud and brash performers, and it scored a very low figure in terms of its internal audience appreciation report - but enough people within the Corporation believed in its potential for a series to be commissioned.

Just Fancy, which began its eleven-year run in January 1951 (and featured, aside from Barker himself, the likes of Pearl Hackney, Deryck Guyler, Desmond Walter Ellis and Kenneth Connor), would go on to prove itself one of the most unusual, imaginative and defiantly unfashionable shows on the wireless at that time (and Barker would judge it 'my favourite and happiest radio series of all'). It did without the usual studio audience, as well as conventional gags, was unafraid of surreal routines, slow-paced sketches or even moments of silence, and, very much reflective of Barker's uncompromising attitude, was content to leave the listener to make their own sense of the nonsense it contained.

One of the most enduringly popular segments of the show featured two old gents, played by Barker and Deryck Guyler, talking to (and sometimes over) each other about very little. The idea for the characters had come to Barker one afternoon when he was at a cricket match, sitting behind a pair of elderly buffers who talked incessantly without ever seeming to listen to what each other was saying.

In this segment, for example, they have temporarily left their usual residence at the Cranbourne Towers Hotel and are making do at another, unexpectedly noisy, guest house nearby, but are just as confused and confusing as ever:

GUYLER: Oh my word... Oh, that was a lovely forty winks... [chuckles to himself] What does he look like? Rupert?

BARKER: [Waking up] Oh...ha...I must have had forty winks, I think. Did you drop off?

GUYLER: Yes, I think I did. It was a good lunch today.

BARKER: Lunch? Yes, not bad at all. What's the time? Good gracious - it's seven o'clock!

GUYLER: That clock always says seven o'clock, doesn't it?

BARKER: Oh yes, so it does...Where's my hunter? It's gone!

GUYLER: What?

BARKER: My hunter! It's gone! I always keep it in this pocket, as you know!

GUYLER: Now, now, let's be calm about it. Now, when did you last have it?

BARKER: Let me think...I went to the jewellers this morning... Of course - I left it there to have the chime repaired, didn't I? Oh dear, I must be getting old, I think.

GUYLER: [Chuckling] The times you do that sort of thing lately! And you get so excited!

BARKER: Yes, I know.

GUYLER: That time you lost your glasses, and they turned up...er...where did they turn up? Er...

BARKER: Yes.

GUYLER: ...Down the back of the chair!

BARKER: It's not turned out to be much of a day after all, has it?

The success of Just Fancy earned Barker another exclusive contract with the BBC, which would see him into the 1960s in regular employment on the radio. He also starred in his own TV show, The Eric Barker Half-Hour (which ran for three series between 1951-3), further extending his fame.

He published his autobiography, Steady, Barker!, in 1956 - a fact that underlines how unfortunate it now is that most people, who know of him solely through his film work, seem to assume that it was only at this point that his career was beginning. The truth is that this was the period in which, after more than twenty years of success on the stage and radio, he was about to start the second phase of his career in cinema.

As the decade had gone on, Barker sounded increasingly frustrated by the changing fashions of the time, mocking the trend for quiz shows and cash competitions that were fast making his own preference for gentle-paced, eccentric and character-driven humour appear somewhat old-fashioned. The consequence was that he was increasingly open to the distraction offered by the film industry.

He had actually made his film debut back in 1937, with a crime short called Carry On London (no relation to the later comedy franchise), followed by a musical-comedy called On Velvet (the fact that some movie database compilers seem to have assumed that only one human being in world history could possibly have possessed a name as exotic as 'Eric Barker' has led to various other, much earlier, credits, for a child actor also called Eric Barker, being wrongly attributed to this Eric Barker).

It was only in the late Fifties, however, that he began to make his mark in the medium (commencing with a role as a barrister in the 1957 satirical comedy Brothers In Law, for which he would win a BAFTA as 'Most Promising Newcomer'), and went on to appear in a quartet of 'proper' Carry Ons (Carry On Sergeant, 1958; Carry On, Constable, 1960; Carry On Spying, 1964; Carry On Emmannuelle, 1978) - as well provide the original story for another (Carry On Cruising, 1962) - and a trio of St Trinian's (Blue Murder At St. Trinian's, 1957; The Pure Hell Of St. Trinian's, 1960; The Great St. Trinian's Train Robbery, 1966), as well as many other popular comedies during the next couple of decades.

He was usually a supporting player with limited screen time, handed characters who mainly reacted to the action going on elsewhere, but he invested these roles with such unforced realism, and such subtle wit, that he drew the audience to him. There was never anything cartoon-like about his contributions, even when the script had suggested it; he knew, and disliked, such types far too well to let them off the hook with a pantomime-like impersonation.

A subversive playing servants, an outrider posing as an insider, he chipped away at each character from within, gleefully yet gently allowing the audience, as the scenes flowed on, to glimpse more of the shiveringly vulnerable, and reluctantly ordinary, human being hiding behind the façade of social superiority. It was always a deft demolition, a subtle skewering, of those who worshipped - and expected others to worship - routine ranks and rules.

Barker was particularly memorable playing the sort of order-obsessed middle-ranking official, usually as attached to a desk as a baby is to a breast, who sought to stall any strategy before it could reach any higher and thus threaten to achieve any success. With his eyebrows arching, his beady little eyes widening behind his black horn-rimmed spectacles, his shoulders jerking up as if a clothes hanger had been rudely reinserted inside his jacket, and his mid-pitched voice threatening to rise all the way up to an agitated squeak, one could see the panic percolating up inside of him as he pondered any plan of action.

No one better captured semi-repressed tetchiness: not quite confident enough that they had sufficient authority to shut people down, but not quite controlled enough to affect an air of indifference, his characters would grow more and more flustered, the body stiffening, the voice slightly quivering, as they struggled to keep their composure while coping with the latest minor crisis. He kept enacting the cruel transition whereby a supposedly important man is reduced to little more than an isolated exclamation mark.

Anything could set these bristling bureaucrats off - clerical errors, a call from head office, an intrusion from a visitor, incorrect application of regulations, questionable syntax - and wind them up into a 'Well, what do you expect me to do about it?' eruption of irritated helplessness. Take, for example, his performance as the chronically irascible Inspector Mills in Carry On, Constable, who gets increasingly rattled by all the individuals he finds roaming freely among his new recruits:

MILLS: [To one constable] You shut your trap, I've had enough of this! [Pointing at another one] And I remember where I've seen you before, too! You're a society playboy. Lothario! You're one of the-the syphon squirters and waiter debaggers of this world!

PC POTTER: Ha-ha, happy days, sir, eh?

MILLS: Happy days? You lot won't know what's hit you soon! [Marches off] Horrible! Disgusting! [Turns back to address his sergeant] I don't want trouble - you can't afford trouble. Right?

SGT WILKINS: Right, sir.

Mills then retreats to his quiet little office, back behind the security blanket of his desk, and scribbles admonitory reports about everyone else. He fumes at the fact that he lacks the power to rid himself of all the disorderly spirits ('If I had my way I'd suspend the whole lot of you from duty immediately, but unfortunately it's out of my hands - it's got to come from higher up') while growing increasingly paranoid about what he suspects is the disrespect being shown to him once his back is turned ('And you!' he barks at the closed door as he imagines the two fingers being thrust on the other side). It is a fine comic performance, free from all clichéd gestures, all-too believable in its portrayal of routine institutional peevishness.

He became so closely-associated with these kinds of characters that it came as no surprise when, early in 1965, he was chosen to play a sort of Jungian distillation of them all in an episode of the popular secret agent series Danger Man called The Ubiquitous Mr Lovegrove. This officious little busybody only existed in the agent John Drake's mind, burrowing into his brain like a recurring bureaucratic nightmare, as he drifted in and out of consciousness after a car accident.

It was a real tour de force from Barker as, revelling in the surrealism of the piece, he kept showing different shades of the same basic figure from one scene to the next. Looking back on it now, the episode could serve as a microcosm of an entire satirical career.

Unfortunately, he would suffer a major stroke soon after recording that memorable appearance, leaving him paralysed down one side and unable to walk. He would only manage to return to work in 1967, seated in his wheelchair, playing the lead role of yet another bad-tempered man, the critic Sheridan Whiteside, in a stage production of The Man Who Came to Dinner.

Defying his doctor's prediction that he would never walk again, he fought and fought and was soon able to stand up and move with the aid of a stick, and would go on acting, and mocking his usual types of character, for another few years, before deciding to retire, in his mid-sixties, and spend more time at his cottage with his beloved wife Pearl. Contributing occasionally to his local BBC radio station in Kent, while Pearl served as a parish councillor as well as continuing with her own acting career, Barker supported various charitable causes and, as a devout Anglican churchman, contributed occasionally as a lay reader. He died on 1st June 1990, aged seventy-eight, at a hospital in Faversham.

He had always played down any praise that he received - 'I am a dull man to myself', he once said, 'full of vexing mannerisms and weaknesses which I cannot throw off' - but he deserved all, and more, of the encomia that came his way. There was never, in truth, anything remotely dull about the bright Eric Barker, but, through the sheer wit and insight of his writing and acting, he captured so well those who were far duller than they ever believed, and exposed their vexing mannerisms and weaknesses for all to see.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreEric Barker - Steady, Barker!: The Autobiography Of Eric Barker

Autobiography of the writer, actor, novelist, director, comedian and broadcasting star Eric Barker.

First published: Sunday 1st January 1956

- Publisher: Secker & Warburg

- Pages: 240

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.