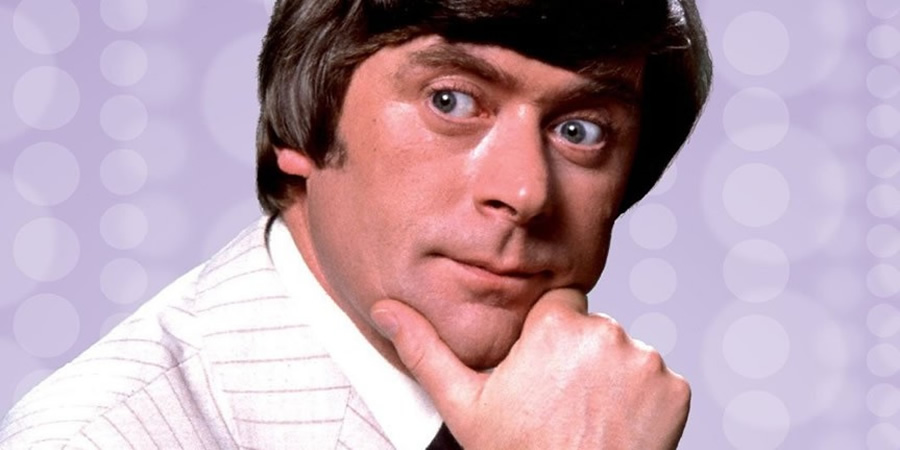

And this was him: The life, art and anxieties of Mike Yarwood

It was good to see how wide and warm were the tributes to Mike Yarwood when he passed away in September of this year. Although he had been largely out of the public eye for more than a couple of decades, he was still remembered, quite rightly, as a major figure in British comic history.

He remains interesting not only for his achievements, but also for his anxieties. The arc of his career is as significant for its decline as it is for its rise.

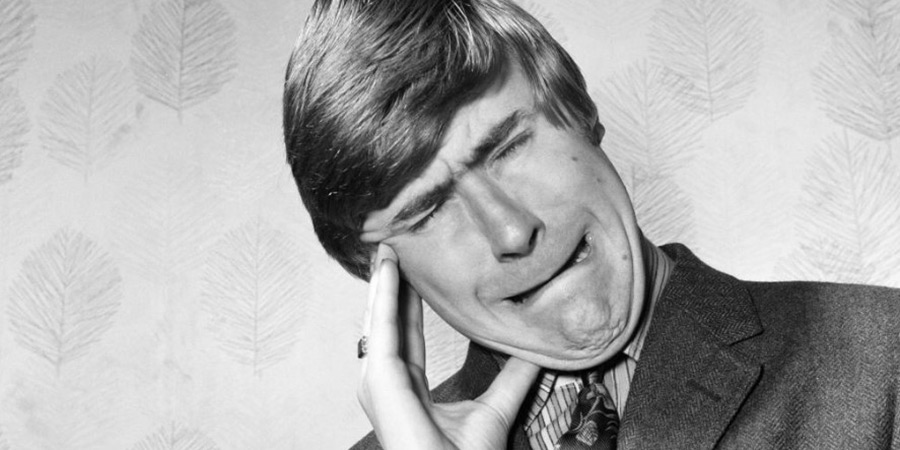

The job of an impressionist has always been an exceptionally high-pressured one. Being funny is difficult enough. Being funny whilst also sounding and acting remarkably like someone else represents another level of difficulty altogether. Mike Yarwood was one of the first, in a mass media age, to take on such a double-barrelled challenge.

It is important, however, to try, at the outset, to put his achievements into some kind of broad and less parochial perspective. Dominant though he was domestically, he was found somewhat wanting internationally.

His Canadian contemporary, Rich Little, occupied a slightly higher level. Better and more biting in his political engagements - his take on Richard Nixon, especially, along with his satirical reflections on Watergate, set the standard for the art - but also often inspired when tackling the more trivial celebrity targets, there was always something more professional, as well as polished, about his performances when compared to those of Yarwood.

There were a number of significant differences between these two stellar impressionists. One of them was simply down to nature: Yarwood had a rather tinny, reedy voice, whereas Little was blessed with a much richer range. This meant that, while Yarwood had to rely on a much more limited array of voices, Little could dip in and out of a far more varied set of levels, from the deep and powerful vocal tones of a Raymond Burr to the much higher and strained sneers of a Don Rickles.

Little was also, by a long way, the more confident of the two as a performer; while Yarwood tended to tense-up when drawn outside of his comfort zone, Little seemed to relish the invitation to run the risks. Little was a regular on the Dean Martin celebrity roasts, when the impressionist had to imitate his target to his face; Yarwood would have dreaded such incessant close-up confrontations.

Yarwood did once dare to impersonate Harold Wilson while sitting next to Harold Wilson, and he did so quite brilliantly, but he already knew Wilson well, and knew that Wilson enjoyed the impression (so much so that he would recommend Yarwood for an OBE in his 1976 resignation honours list), and such a face-to-face situation, in his case, was very much the exception to the rule. Little, on the other hand, would regularly impersonate his subjects whilst in their presence, often without any strong sense of how well or badly they would take it, and he was fearless in the way he attacked such challenges (see, for example, the way he 'taught' Jimmy Stewart to 'do' Jimmy Stewart - an astonishing performance that Stewart himself later described as 'unnervingly magical' - and his similarly inspired incarnation as Johnny Carson, adding one telling tic after another until the personality was complete, right in front of the notoriously prickly talk show host).

Another aspect in which Little out-performed Yarwood was not so much in listening to his subjects, but more so in continuing to listen to them. Little's Cary Grant impression, for example, aged as Grant aged, growing deeper and throatier as the years went by. Yarwood, in contrast, had a tendency to stick with his first take on his impressions, with the likes of his Ken Dodd, for instance, retaining the strength and exuberance of youth long after the 'real thing' grew much breathier and more laboured.

In the British context, nonetheless, there was no one to match Mike Yarwood - and (in contrast to Little's situation, where there were several talented rivals in circulation) no one to push him. There were one or two other impressionists around - Peter Goodwright, for example, was a very capable and likeable performer - but none who ever threatened to knock him off his perch. He was the one who took the skill centre stage, he was the one who made it seem like an essential part of popular entertainment, and he was the one who captivated the current, and the next, generation of copyists.

There were three basic stages in Yarwood's career. The first was as a turn; the second was as a star; the third was as a problem.

The first stage was, for him, the happiest. It saw him find a voice, find multiple voices, go on stage, do his act, and go home.

He had always been able to listen, imitate and amuse. Born Michael Edward Yarwood in the Cheshire village of Bredbury in 1941, he first started eliciting a reaction to his efforts at the age of about six, when he made some of his family laugh (but not his mother, who thought it was rude) by stuffing a cushion up his sweater and copying Gerald Campion's portrayal of Billy Bunter from TV. Once he realised that he could achieve that kind of rewarding effect, even if it was for seeming to be who he was not rather than who he was, he proceeded to use his gift for mimicry more deliberately as a means of masking his essential shyness as he mixed with others at school.

After finishing his education, having failed his 11+, at the age of fifteen (his teachers marked his departure by inviting him into the staff room to impersonate each one of them in turn), he drifted in and out of a number of uninspiring jobs - messenger, salesman, trainee footballer - before trying his hand at being a stand-up comic on the northern pub and club circuit. This is when mimicry helped mask another problem: namely, the weakness of his material.

He dodged in and out of impressions, as if using them as a shield, depending upon the quality of each gag, and they helped him get laughs with lines that otherwise would have fallen flat. That was enough, after a while, to get him work as a warm-up man for television shows such as Comedy Bandbox, which in turn was enough to get him the odd spot in front of the cameras as an act in his own right.

By the mid-1960s, guided by his mentor and first producer Royston Mayoh (who taught him stage craft and then studio craft), he started shining in guest spots on such high-profile shows as Sunday Night At The London Palladium, with his impressions now established as the defining element of his routines. The critics started to take note of his progress, with one of them remarking perceptively that he 'not only captures the voice and accent of his victims, he [also] seems to get to the very spirit of them'.

Driven on by his distinctive talent, he also had the good fortune to find himself very much in the right place at the right time. The first reason for this was that northern entertainers, thanks especially to The Beatles in music and Ken Dodd in comedy, were now coming to dominate the country's popular culture, and Yarwood, as someone from the north himself, was very comfortable capturing accurately their accents as well as their characters. The second reason was that Harold Wilson, whose self-consciously modulated Yorkshire accent and nasally tinny vocal timbre suited Yarwood better than any of the other political grandees of the time, had just risen to power as the new Prime Minister.

The third reason was that, after several years of overtly provocative satirical TV comedy via the likes of That Was The Week That Was, broadcasters were looking for a more playful, and less legally hazardous, approach to political humour, and here was precisely the performer they craved. Always more of a Hogarth than a Gillray, he never went in blade glinting for the kill, but, every now and then, he slipped in for one or two flesh wounds, and he inflicted them all with a smile.

It made Yarwood's repertory of imitations seem increasingly on point as well as on target. It also helped that this was happening just as terrestrial television was entering into its most effectively intense era, with audiences rising into the multimillions, all of them united with a common range of cultural reference points. A good impressionist, in such a context, could become a comic commentator for the whole nation, and that, indeed, is what Mike Yarwood went on to be.

He graduated from a turn into a star with the arrival in 1968 of the first of his own series for ATV, Will The Real Mike Yarwood Stand Up?. Quickly establishing the basic format of character-driven stand-up and sketches broken up by one or two musical guests, the show won Yarwood some outstandingly positive reviews.

'Fantastic, an over-worked word and one frequently misused, must surely be the only correct description for the talents of Yarwood,' wrote one critic. 'His impersonations, particularly of David Frost, were so authentic that it is a wonder the characters he portrays can remain in business.'

His career was further advanced when, in 1971, he moved over to the BBC for a show called Look - Mike Yarwood. Bill Cotton, the BBC's recently-installed new Head of Light Entertainment, had known him for some time, admired him greatly, and signed him up to be part of his ambitious plans to make the BBC the unrivalled provider of high-quality popular variety, music and comedy.

It worked. Mike Yarwood, throughout the rest of the 1970s, would be considered one of the jewels in the Corporation's entertainment crown, alongside the likes of Morecambe & Wise, Dave Allen, The Two Ronnies, Bruce Forsyth and Dick Emery.

The first and most obvious reason for this was his exceptional talent. Like all of the other performers that Cotton was so keen to collect, he had the right ability, and attitude, to appeal to and also impress a mass audience.

Secondly, he was a genuinely likeable personality. Cotton wanted his stars to establish and maintain strong long-term relationships with the viewing audience, and that only worked if there seemed to be something authentically amiable about the artists concerned. Yarwood was a nice (and rather vulnerable) man as well as a talented one, and that personal quality shone through.

The third reason was that, as Cotton ensured with all of those key programmes he oversaw, Mike Yarwood was surrounded and supported by an exceptionally able and professional production team. His show featured numerous top comedy writers, such as Eric Davidson, Spike Mullins, Eric Merriman, Neil Shand, David Renwick and Lawrie Kinsley; a superb technical crew; and some of the best producer/directors in the business, including, at various times, Michael Hurll, James Moir and John Ammonds.

It was the synthesis of these three things that made the show sparkle. Week after week, year after year, it kept itself fresh, it kept itself competitive and it kept itself engaging, peaking, in terms of audience figures, with a Christmas special in 1977 that attracted a record 21.4 million viewers.

As a showcase for a mainstream impressionist, it was, and remains, unrivalled. It helped Yarwood to change the common perception of what he and others did from being a 'speciality act,' a relatively trivial trick, to a proper comic art.

His eye for detail, during these peak years, was often so unnerving for his subjects that it could push them towards paralysis if they allowed the impression to creep too deep into their consciousness. Yarwood's slight exaggeration of Michael Parkinson's repertoire of physical tics - such as the earlobe fiddle, the nose pick and the elbow pump that suggested he was trying to combat a slow puncture - left the talk show host so acutely self-conscious that he had to avoid seeing them copied for quite some time, while Harold Wilson's own expression, when he once saw Yarwood, in his presence, perfectly replicate his playing-for-time ploy of lighting his pipe whilst glancing up and to the side as he repeatedly blinked and smiled, radiated a grudging 'the game's up' recognition.

One of his other great strengths was the fact that, so closely-attuned was he to some of his subjects, his occasional 'embellishments' - such as a high-pitched part-bleat/part-chuckle for Wilson, an excited yodel for the 'up and under' rugby league commentator Eddie Waring, a dry gargle for the political inquisitor Robin Day or a shiny-lipped reptilian smirk for Bob Monkhouse - appeared such natural comic encrustations that they seemed, in time, to sink within their subjects' actual flesh. The Labour chancellor Denis Healey, indeed, was so taken with the popularity of Yarwood's warm and rhythmic 'silly-billy' catchphrase for his character that he ended up assimilating it himself.

The strain of maintaining such high standards, however, gradually made Yarwood's stardom a problem. 'My fondest memories,' he would later say when looking back on his whole career, 'are when I was a supporting act. When I was doing The Mike Yarwood Show, I'd walk into the television studio and see all these people working on one project, all because of me, and I wanted to run away'.

He grew increasingly neurotic, developing a long list of peculiar rituals in the hope of calming himself down during the build-up to performances - one of these involved the refusal to eat anything that required chewing, because, he said, he could not bear to hear the 'noise' of his jaws opening and closing - and he found it harder and harder to make any crucial decisions. Each new success only seemed to fuel his fear of failure.

'I was worrying more about everything,' he would later admit. 'Have I got enough characters? Is the script going to be funny enough? Are we doing too many shows? Are the ratings going to stay high? Everything was eating away at me'.

All impressionists tend to a greater degree of insecurity than other types of entertainers for the simple reason that so much of their relevance is parasitic upon the relevance of their subjects. If the celebrities whom they copy start to decline, so, too, will the impressionist, unless they can master a new and younger set of replacements.

The second half of the 1970s saw so many of Yarwood's favourite subjects - such as Harold Wilson, Ted Heath, Harry H. Corbett and Wilfrid Brambell, Max Bygraves, Harry Worth and Malcolm Muggeridge - fall, for one reason or another, out of fashion that his act suddenly started looking outdated. His prospects of responding positively to this challenge, by incorporating a new up-and-coming generation of targets - a task already compromised by the fact that, physically as well as emotionally, it is far harder to capture the voice of someone younger, rather than older, than oneself - were further undermined by both the rise to power of Margaret Thatcher (his initial ill-considered attempt to dress up in drag to imitate her betrayed his growing sense of panic) and the first stirrings of alternative comedy (which was hard for him to mock when it was mocking, amongst many 'traditional' performers, himself).

His alcoholism, of course, was another factor in his decline. He had, since relatively early in his TV career, been troubled by nerves before performances and drank increasingly heavily to overcome them. The greater the success he achieved, the more intense was the pressure he felt to sustain it, and the more reliant he became on alcohol, and the more it, in turn, affected his personal and professional life. 'Just being who I was,' he would say, 'was too much for me'.

Arguably an even greater factor in Yarwood's descent from stardom concerned the consequences of his decision, in the second half of the Seventies, to be an impersonator as well as an impressionist, obsessing first as much, and then more than, on the look as he did on the sound of his subjects. He thought, as he strained to stay at the top, that this would accentuate his achievement; the reality was that, increasingly, it diminished it.

At the peak of his powers, he had only required the most basic of props - such as a pair of spectacles for the likes of Eric Morecambe or Robin Day, a pipe for Harold Wilson or a fez for Tommy Cooper - to accentuate his imitations, and, indeed, many of his best and most popular routines only required a quick ruffle of the hair or a sudden change of facial expression to help summon his subject into being.

That was an important aspect of his magic. The real art came from behind the eyes, not in front of the face. He didn't need to hide behind make-up or costumes for his audience to suspend their disbelief. All he needed, at his very best, was the spirit to complement the sound.

Yarwood used to be eminently clear and committed about this. Speaking in 1967, for example, he said: 'I never use wigs because I think it is cheating. [...] I just go for the expressions and mannerisms. I might wear the sort of things they wear, but I don't try to change my whole appearance because anybody can do that.'.

By the late 1970s, however, his attitude had started to change. Rather than continue to build his characters from the inside out, he began to concentrate more on building them from the outside in.

His producer of the time, John Ammonds, recalled his own frustration as he saw this change start to happen. He told me:

It was a confidence thing, I think, but Mike started to get more and more obsessed with looking like the people he was impersonating. He spent more and more time getting the make-up just right, the clothes just right, the hair just right, and so on and on. Now, he felt that this was helping him improve the impression, but I felt it was doing the opposite, because it was as if he was hiding inside of all this make-up and stuff. It was as though he was trying, without being entirely aware of it, to compensate for his doubts about the actual voice he was doing.

I suppose the way he used to do it, just straight to camera, made him feel very exposed, and as his nervousness got worse, I think he was sort of running away from that. So while I was trying to get him to just concentrate on the actual impression itself, trying to make him work harder at that - and to be honest I don't think he was working as hard as he used to do, at least away from the rehearsal room - he was distracting himself, in my view, with all of this other business.

And he also wanted all of these multi-image, split screen things, you know, increasingly complicated camera set-ups and special effects, for his sketches, which took a long, long time to do, and they ended up all right - thanks in large part to Alan Boyd, my assistant, who was really good editing the video - but I did feel that Mike was getting away from doing what he did best - which was the voice. And that was sad.

The technical complexity led to slower-paced sketches and 'stiffer' performances - especially the pre-recorded sequences where Yarwood had to act opposite himself, or several 'selves' - and, more generally, a less engaging style of show. The polish might have been a little brighter, but it came at the cost of the personality.

A lucrative move to Thames Television in 1982 (which was announced with rare bitterness by the BBC in a statement that said: 'we have come to the parting of the ways - over money') only accelerated this process, with the emergence of a new generation of impressionists (who, ironically, had been inspired by him and his earlier shows) only highlighting the decline in energy, sharpness and relevance of his own efforts. Ammonds, who was brought back to work with him again at Thames, would later recall for me how much worse this concentration on vision at the expense of sound had now grown:

I'll give you an example: Neil Kinnock. Now, I'd felt for a while that Mike was too slow at bringing in new impressions - we'd argued a bit about that - so I was always pleased when he did want to do someone 'new,' but once again he'd start fussing over the look rather than keep working harder on the voice.

He'd want to look exactly like Kinnock, but his face wasn't the right shape. It was easier when he did, say, Ronald Reagan, because Reagan's forehead is quite high, like Mike's. But Kinnock's forehead went straight back, so to speak, so Mike would forever be asking the make-up people to come up with some kind of solution.

And I'd be saying to him, 'Look, Mike, it doesn't matter, it really doesn't matter. You don't have to look just like the person. What matters is: how accurate is the voice and how funny is the material. Stop worrying about the look!' But he didn't. He got worse. And they indulged him far more at Thames than they had done at the BBC. They allowed him more and more time to fuss over getting the look right, and he spent less and less time getting the voice right. It was tragic, in a way. He just lost sight of, or lost belief in, what had made him so good and so special.

Mike Yarwood In Persons - which began in January 1983 and ran for two series into the following year - was by no means a flop, but it certainly fell short of expectations in terms of its audience figures (which started at a healthy 13m and then started slowly to slide down into single figures), and the critics were fairly quick to fasten on its flaws. Many complained about the 'over-familiarity' of his range of impressions, and his decidedly shaky singing (likened by one to the sound of a 'cat being thrown through a window'), and how many 'distractions' there were in what was now only a half-hour show, with the use of dance routines ('by a troupe of tired old hoofers who look as if they've escaped from Cruft's') coming in for particular criticism alongside the over-reliance on technical 'gimmicks'.

1985 would be Yarwood's annus horribilis. In the space of a few months, his marriage broke up, Thames scrapped its plans (which he had already made public) for another series, and, after a hard-earned dry period, he started drinking again. One journalist who met him during this time lamented that his conversation was so full of 'fear, doom and gloom' that it seemed as though the very air was set to rain 'tears of salt, if not blood, from his wrung-out soul'.

The following year would not be much better. There was a rather desperate-looking personal makeover, with a boyish new hairstyle and more youthful styles of outfits, and three more ITV specials, each one of which tinkered with his traditional format in the hope of reviving his fortunes, but with diminishing returns. He and various producers also made some significant losses from his live shows, with reports of attendances declining significantly in a number of provincial venues ('I started to be able to see the colour of the seats,' he later admitted).

At the end of 1987, following one final and rather half-hearted Christmas special, Thames TV decided not to renew its contract with Mike Yarwood. Aside in the months ahead from the odd brief appearance here and there on the small screen as merely a guest, he was left with no real option but to concentrate on theatre and club work.

Television already looked to have moved on. Other impressionists - livelier, cheekier, in some cases more daring - were already queuing up to take his place via such ensemble shows as Copy Cats and Spitting Image, and one or two - such as Phil Cool and Rory Bremner - were already starring in their own series. There seemed no way back now for Yarwood, even though he was still only in his late-forties.

'It's like a parking space,' he would say. 'If you're away from it for too long, you'll return and find that somebody else has taken it over'.

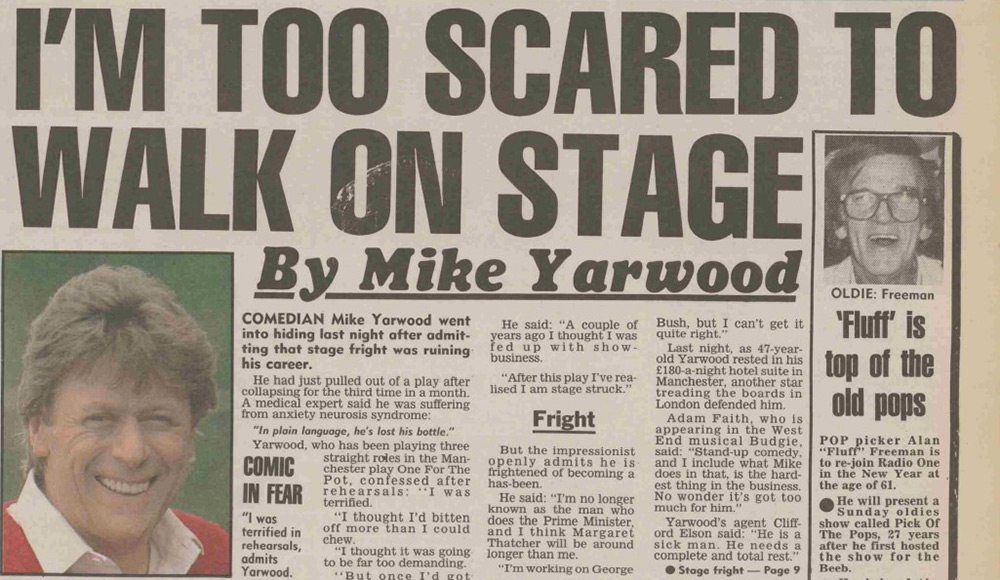

The next few years saw several failed attempts at reinvention. In the autumn of 1988, after announcing his intention of exploring some opportunities as an actor, he collapsed three times on stage in the space of a month through what was described as 'anxiety neurosis' while in a touring version of the Ray Cooney farce One For The Pot; he was ordered by doctors to drop out of the production (he was replaced by Nicholas Bailey), as well as cancel a planned appearance in pantomime later the same year. His agent of the time admitted: 'Mike is very depressed and unwell, and he will take as long as is needed before resuming his career'.

He did return in the summer of 1989 with a new plan, seemingly out of nowhere, to become a chat show host for Grampian TV. A pilot of Mike Yarwood In Conversation was filmed, featuring him interviewing Anthony Hopkins (contrary to some accounts, it was broadcast, but not in all ITV regions and not until a couple of years later), and sources at Grampian claimed that they were so encouraged by the results that work was under way for 'at least two more' episodes. The project, however, was soon quietly abandoned.

Yarwood, by this stage, was clearly in a very vulnerable state of mind. He was even (he would later say, laughing at the black humour of it all) having panic attacks on his way to seeing psychiatrists about his panic attacks, and his confidence was quicker than ever to crumble.

Already rattled by the increasingly common tendency of the tabloids to refer to him as a 'fading funnyman', he threatened to sue one newspaper when it claimed that a recent 'comeback' appearance he had made at an awards event had been an embarrassing flop (even though several other publications had carried very similar reports). He contended, furiously, that it had made him seem like 'an incompetent performer'. His solicitors persuaded him, eventually, to abandon the case.

A subsequent visit to Los Angeles to promote Virgin Airlines prompted more negative publicity when, during a planned performance at a Santa Monica hotel, he walked off the stage only a minute or so into his act, then later upset other guests by launching into an impromptu and tasteless Sammy Davis Jnr impression only hours before the singer's funeral, and then clashed angrily with Virgin staff during the flight home. The only explanation his agent could offer was that he 'had been a bit upset'.

This desperately sad period culminated in July 1990 with him being admitted to hospital after suffering a heart attack at his home in Weybridge, Surrey. Although there was an initial attempt to have it reported as merely a 'chest infection', he soon decided to make the truth public. It would turn out to be the wake-up call that he needed to quit drinking for good the following year.

As his health improved (he would also, at a later stage, undergo treatment for depression at the Priory Clinic), there would be a few more sightings of him every now and then on the screen, including appearances on Des O'Connor Tonight and The Royal Variety Performance in 1993, doing an impression of the then-Prime Minister John Major on both occasions; the May 1995 BBC special Call Up The Stars, a recreation of a 1940s wartime concert in which he appeared as Max Miller; a somewhat uneasy guest appearance on Have I Got News For You in November 1995, and then an undemanding role as host of the one-off BBC clips show All The Best For Christmas; and then there was also, very touchingly, an honest and engaging chat on stage with one of his old targets, Bob Monkhouse, in 2003. There was no longer, however, any sense that such contributions would reignite his career.

'It was never difficult to get Mike Yarwood work,' his latest agent, Laurie Mansfield, would say of this period. 'It was always difficult to get Mike Yarwood to go to work'.

The truth was that, for the first time in his life, he was at last getting used to having his own persona. Financially secure, he was able to relax, do what he wanted, and enjoy his relationships with his two always-supportive daughters, Charlotte and Clare, and the grandchildren on whom he now doted.

He would spend his final couple of years at the Royal Variety Charity's nursing home Brinsworth House, in Twickenham, South West London, for whose upkeep he used to help raise funds. Those who knew him there would say that he was happy and contented, still doing impressions, and still making people laugh.

When he passed away, at the age of eighty-two, on 8 September, his fellow impressionists - Rory Bremner, Jon Culshaw, Alistair McGowan, Kate Robbins, Steve Nallon and so many others - were among those who paid tribute, calling him 'The Gov'nor,' and acknowledging that, without him, they would never have had such a career. One can only hope, however, that he knew, in the end, that he would be missed not just for having been others, but also for having been the very good, the very kind and the very talented person that was Mike Yarwood.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more