The ITV Job: The day when the BBC almost lost British comedy

Some stories, like a bullet whizzing narrowly past an ear, don't end with a big bang, but they still leave you thinking, with a shudder, about what might so easily have been. This is one of those stories.

It is about an attempt to pull off one of the most audacious coups in the history of British broadcasting. It is about the time when, just after the BBC lost its monopoly, the nation's brand new commercial network hatched a plan to monopolise the country's comedy.

This was, of course, merely the first in what would turn out to be a long and wriggling line of bids by ITV to undermine the BBC. Rather than fully embrace the onerous challenge of actually trying to counter its competitor's successes - by striving to create and cultivate similar triumphs all of its own - it has, on a number of notable occasions, preferred to poach the best of what, and whom, the Corporation has prepared earlier.

Indeed, its attitude to the BBC over the decades has sometimes resembled that of Peter Cook's impatient and tin-eared millionaire Mr Stigwell to Dudley Moore's principled but poor piano teacher Blanfeddy: 'I like your style. I like the cut of your jib. Integrity! That's a valuable thing and I'm willing to pay for it!' As if to prove the point, and in the process stamp down on irony like a jackboot squashing the most delicate of worms, ITV proceeded to hand Cook and Moore themselves a hefty raise, two years after they performed this sketch, so that they, too, would abandon the BBC and swap sides ('That's more like it, boy!').

To be fair, such actions are only to be expected when one sticks a small island of public service broadcasting in the middle of a vast sea of commercial operators. One has to accept the fact that there will be plenty of sharks swimming ominously close to the shore.

Whenever they pounce, however, it can be quite a brutal and bloody sight to see.

In the space of a couple of years in the late 1970s, for example, ITV tried to tear the beating heart out of its rival's prime time entertainment output by luring not only Morecambe & Wise but also Bruce Forsyth and Dick Emery over to 'the other side'. It pursued a similar plan for the news, talks and consumer affairs sectors when, in 1980, it coaxed Michael Parkinson, Angela Rippon and (albeit briefly) Esther Rantzen, along with a number of backroom staff, over to help plan and launch TV-am.

Then, of course, there was ITV's so-called 'Snatch of the Day' in 1988 (following on from an aborted £9m attempt a decade earlier), when it shelled out the then eye-watering sum of £44 million to abruptly block the BBC's access to top-flight football (and then did much the same thing again, in 2000, at the even more dramatic cost of £183 million, as well as another deal, in 2013, for exclusive rights to all of England's friendly and qualifying internationals). It also headhunted the BBC's top sports executives, first Brian Barwick and then Niall Sloane, as well as its top presenter, Desmond ('The BBC is a cause, not a job') Lynam.

Such prêt-à-porter pouncing has never really stopped. There was even an attempt, in 2010, to blunt the burgeoning popularity of the BBC's early evening staple The One Show when ITV's director of television Peter Fincham (the very man who had launched the show before himself upping sticks and shooting over to the other side) plucked its two most familiar presenters, Adrian Chiles and Christine Bleakley, straight off their cheap and cheerful pegs, for what was reported to be a pair of 'multi-million pound deals,' to try to replicate their 'chemistry' in the mornings on Daybreak.

The fact that most of these noisy blows to the BBC were soon followed by the even-louder sound of ITV shooting itself in the foot with the best Beretta that money can buy suggests either that there was, repeatedly, an extraordinary amount of incompetence at production level, or else the desire to inflict damage on a competitor was actually far greater, and far more carefully thought-out, than was the dream of actually doing something genuinely decent with whatever was grabbed from out of the swag bag.

The very first attempt back in the Fifties, however, would aim to inflict far greater damage on the nation's public service broadcaster - at least as far as its role as a producer of entertainment was concerned - than any of the jabs and japes that followed. ITV, back then, did not just want to blow the bloody doors off; it wanted to blow the whole bloody thing sky-high.

The object of the operation was to take control of British comedy. The means of doing so was to buy-up Britain's comedy writers.

Ted Kavanagh was the man who, entirely unwittingly, started the whole process in motion several years earlier when he decided to provide his fellow comedy writers with some proper representation and commercial clout by forming his own agency. Having written for, amongst others, Tommy Handley since the mid-1920s, he reached a collaborative peak with the comic during the Second World War with their incredibly popular radio sketch show ITMA. Thanks to Kavanagh's scripts full of memorable characters and infectious catchphrases, along with Handley's fast and friendly style of delivery, the show had become a kind of national treasure, a much-needed source of weekly relief as the bombs kept on dropping and the anxieties kept on rising.

Kavanagh, as a consequence, was probably the best-paid comedy writer working for the BBC at that time. He was keenly aware, however, that most of his colleagues were far more meanly-remunerated for their many hours of labour. He also knew that comedy writers generally, in comparison with their contemporaries in the 'legitimate theatre' and movie industries, were often treated like second-class citizens as mere 'gag writers', and therefore found it much harder to win any kind of formal representation to promote their careers and protect themselves from exploitation.

This led to Kavanagh (a kind-hearted man who was already well-known for his generosity to those who were down on their luck) resolving to take personal responsibility for putting matters right for other members of his profession. He decided to invest a large amount his own personal savings and start up an agency - a self-preservation society of sorts - aimed primarily at comedy writers.

Ted Kavanagh Associated Ltd was thus established shortly after the end of the war, on 17th September 1945, in offices at 8 Waterloo Place in London. Starting with four staff writers (E.A. Maguire, Warren Tute, Rodney Hobson and Terry Stafford), and about thirty 'associates' (who included Gale Pedrick, Colin Wills and Roy Plomley), it was, within its first year, not just supplying all of the comic material for ITMA, as well as plenty of scripts for other BBC radio and television shows, but was also already beginning to dominate the comedy scriptwriting input at theatres and clubs for revues, plays, stand-up spots, summer seasons and pantomimes.

Expanding at a rapid rate, it started finding and nurturing a whole new generation of comic writing talents who were flooding back into civilian life from the Forces. Among the new names being added to its books would be the rapidly in-demand all-rounder Sid Colin and the two soon-to-be hugely successful duos of Frank Muir and Denis Norden, and Bob Monkhouse and Denis Goodwin.

The agency was not just attractive to writers because it replaced the old hit-and-miss strategy of trying to sell scripts 'on spec' with far more professional processes for seeking and securing them work, thus winning them a better, and more regular, form of income. It also identified and looked after their legal rights as authors, ensuring proper public recognition of their contributions. Indeed, Kavanagh made it clear quite early on that he was not afraid to take either individuals or institutions to court on behalf of his clients if he ever considered that it was necessary (such as when, in 1951, he sued successfully the movie producer Victor Katona after the latter had failed to pay for, and credit, a rewrite of one of his company's screenplays).

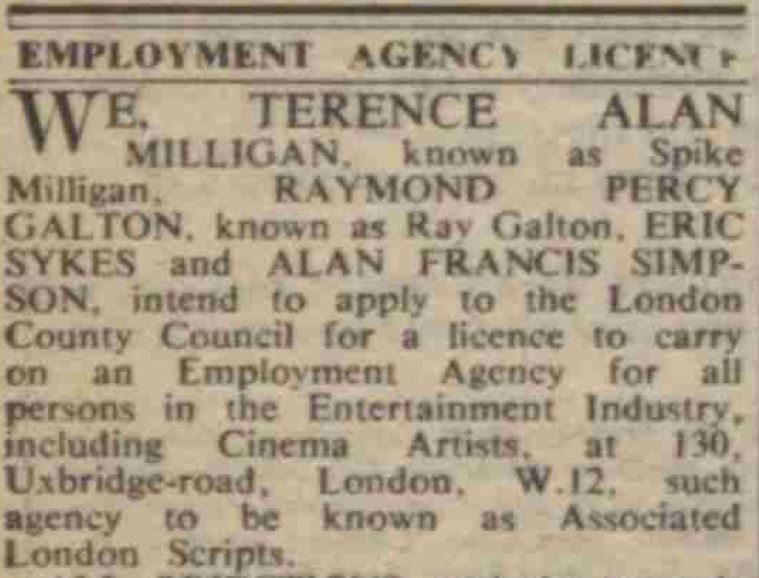

It came as no great surprise, therefore, when others in the business started looking to get in on the act, but possibly on more favourable terms, and, sure enough, the Kavanagh agency was joined in September 1954 by a rival company called Associated London Scripts. Based originally in offices at 130 Uxbridge Road, it was co-founded by Spike Milligan, Eric Sykes and Ray Galton and Alan Simpson because they wanted to take more or less full control over their careers, not only dictating terms but also, increasingly, dictating projects.

What would distinguish ALS from Kavanagh's company was that, whereas the latter had been modelled on the traditional theatrical agencies - complete with a rather stuffily bureaucratic structure and the usual system of commissions - the former had been conceived as a much more informal, but strongly idealistic, 'writers' co-operative'. The scriptwriters at ALS aimed, basically, to cut out the middle man and be their own agents.

That would not quite be how things turned out, as Milligan and Co soon realised that they were far too busy writing and thinking to also be negotiating, and so their young but exceptionally smart secretary, Beryl Vertue, gradually 'evolved' into their shared manager and agent, but everyone continued to pool the same proportion (ten per cent) of their respective resources into the company, and ALS acquired a reputation for being the most creative, and productive, independent source of comic material, and programme ideas, in the country.

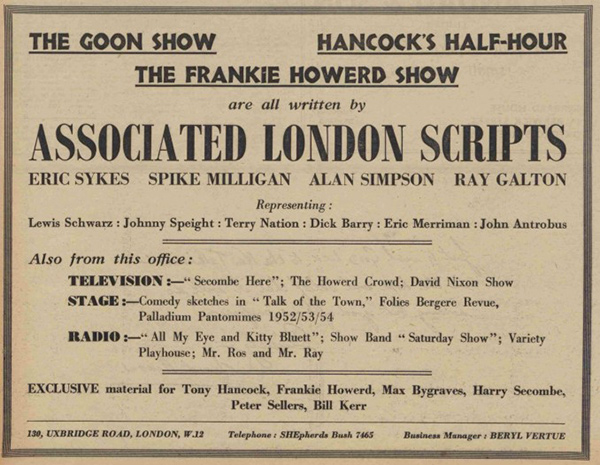

It also did not take long, given the high-profile names of the original owners, for the company to start complementing (more so than just rivalling) Kavanagh's roster with its own fast-expanding collection of younger, hungrier and often less conventional kinds of clients. The list would soon grow to include the likes of Johnny Speight, Terry Nation, Dick Barry, Brad Ashton, Dick Vosburgh, John Junkin, Lew Schwarz, John Antrobus, Barry Took and Eric Merriman.

By the middle of the decade, therefore, Kavanagh Associates and ALS were, between them, responsible for the vast majority of the best comic (as well as many of the best drama) scriptwriters in Britain, and the BBC, having overcome the initial shock of no longer being able to dictate its own terms (and beginning to see the benefits of dealing with organised groups rather than disorganised individuals), was now getting used to haggling with both of these bodies to satisfy nearly all of its entertainment needs. From The Goon Show to Hancock's Half Hour, Take It From Here to Fast And Loose, How Do You View? to The Howerd Crowd, the invoices were usually emanating from one or the other of these agencies.

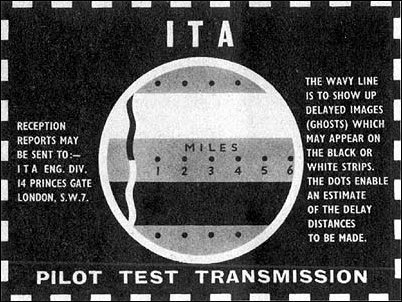

This is the point where ITV came in. The Television Act of 1954 made it possible for a collection of regional companies to be formed which would contribute to a national network of Independent Television. The BBC's monopoly was about to end; competition was coming.

There was some division at the time as to how good or bad a thing this was going to be (with some excited that populist tastes and interests would acquire more power and prominence, and others fearful of the market muscling-out real diversity and daring), but all seemed to agree that, given the influx of advertising and other commercial opportunities, all of the new regional franchises represented, as one observer at the time (Scottish TV's Roy Thomson) famously put it, 'a permit to print money'.

The appeal to the agencies of the change was obvious: more and more shows requiring more and more scripts, and increasingly fierce competition to hike up the price of hiring the best scriptwriters. Both Kavanagh Associates and ALS, therefore, were rubbing their hands in anticipation of the benefits that were about to come.

ITV itself, however, had other ideas. Ironically, one of the first actions of a couple of British broadcasting's first commercial companies was a clandestine attempt to eliminate the competition.

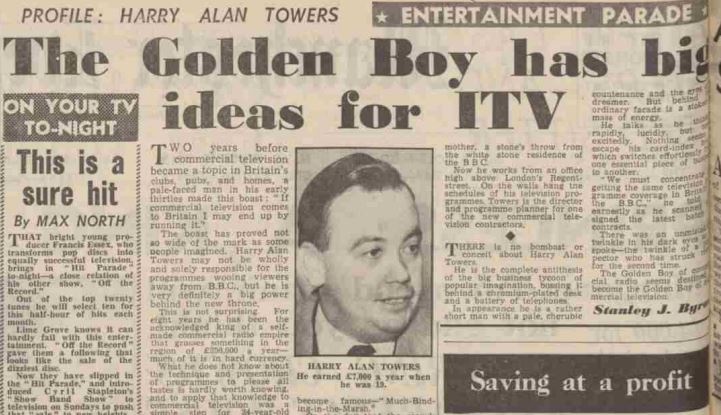

It all started one morning fairly early into 1955 with a telephone call, quite out of the blue, to Kavanagh Associates. It was from a man named Harry Alan Towers.

A talent spotter, impresario, international entrepreneur, stringer, screenwriter, supplier of syndicated radio shows, possibly (at least according to the FBI) a part-time Soviet spy and certainly a man with a sniffer-dog sensitivity to the slightest scent of any new means to make some money, the fast-talking, fast-moving, thirty-four-year-old Harry Alan Towers was, by his own admission, 'a bit of a rascal' who was always 'up to something'. What he was up to now, however, was something potentially very big indeed.

Having thrown himself into the race to get involved as soon as the prospect of commercial television first arose (his connections with the Daily Mail, whose owner Associated Newspapers was eager to invest, allowed him to jam his foot in the door), he had by this stage manoeuvred himself into a predictably fluid and ambiguous unofficial role - part investor, part gofer and part consigliere - that saw him move back and forth between the various interested parties (who included the former BBC executive Norman Collins; the head of electronic equipment manufacturers Pye, Charles Orr Stanley; the industrialist Sir Robert Renwick; the managing director of multiple theatre chains Prince Littler; the boss of the Moss Empire theatre chain Val Parnell; and the talent agents Mike Nidorf and Lew and Leslie Grade), running errands, circulating messages, calming quarrels and helping to organise ad hoc low-key meetings.

One of his most important ongoing duties during this period was discreetly sounding-out some of the BBC's top managers, producers, directors and technicians with a view to signing them up to commercial TV. He had already got the nod from the likes of the well-regarded producer/director Bill Ward, technical engineer Terence MacNamara, outside broadcast specialists Keith Rogers, Frank Beale and Philip Dorte, and director Leonard Mathews, and more names seemed to get added every few days.

He was also being dispatched to address various assemblages of industry groups and unions and 'sell' the commercial TV venture to them as a positive rather than a negative move for their members. A fluent and engaging speaker, he was fighting fires at a rapid rate.

Concurrently, but more self-servingly, he was busy beefing up his own production company, Towers of London, so that it would be ready to supply his new colleagues with plenty of cheaply-made programmes from its base at Highbury Studios in north London. Another company - TV Commercials Ltd - was in the process of being developed, with the help of a couple of business associates, to make some of the ads for the new channels inside a specially-converted old cinema in Barnes.

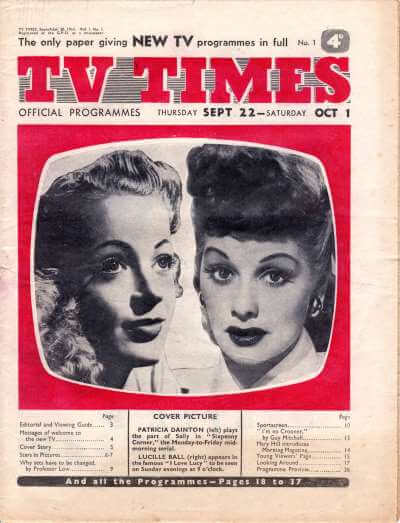

Towers was also in regular touch, on behalf of all his associates (most of whom would soon end up grouping together formally as ATV - which would serve the London region at weekends - with the others gathering at Associated-Rediffusion - which would serve London during the week), with sources in New York to prepare for the purchasing of the cream of America's syndicated TV shows, including the much-coveted ratings winner I Love Lucy. Knowing that the BBC, as previously the sole UK-based customer, had neglected to secure any exclusive arrangements, Towers was flying back and forth across the Atlantic, quietly putting some of the lucrative new deals in place.

He had now been charged with the additional task of contacting Kavanagh Associates because he was known to be an old acquaintance of its owner, having contributed the odd idea for ITMA back in the 1940s when he himself was working regularly in radio. The call, therefore, came in.

Ted Kavanagh, who had long been resigned to the realisation that one could never quite know what was fact and what was fiction when Harry Alan Towers was touting some new project, listened patiently as his caller laid on more and more layers of mystery as he kept referring vaguely to important people and exciting plans and the possibility of making fortunes for a privileged coterie of people. Towers concluded by inviting Kavanagh or a designated representative to a meeting pencilled-in for the middle of the following week, but then added that not only would the directors at Associated London Scripts be asked to attend as well, but also that he wanted Kavanagh to issue them the invitation.

Whether Kavanagh understood why Towers was so keen to cover over some of his own tracks like this, or was simply happy to indulge for a while what was already sounding like some kind of creaky B-movie cloak-and-dagger script, is open to conjecture. He did, however, do as he had been requested and dialled-up ALS.

So now it was their turn, out of the blue, to listen to these intriguing bits and pieces, try to piece them all together, and work out what this breathless waffle was actually all about. Left feeling as unsure but also as curious as Kavanagh already was, they agreed, like he had done, to go to the meeting (set to be held in the Regent Street offices that Towers shared with his redoubtable assistant - his mother, Margaret) and see just what secrets would actually be spilled.

What actually happened there, the following week would not be recorded, and was definitely not intended for the history books. Fortunately, however, many decades later, a few of the details would be recalled for me by some of those who took part.

'I remember it vividly,' Alan Simpson, of ALS, would say:

The Kavanagh agency had arranged the meeting with a consortium of ATV, Associated-Rediffusion, Leslie Grade and Harry Alan Towers, and it turned out that it was to discuss the new ITV contract that was coming up - the formation of ITV. So we, the writers, had this meeting with them. There were seven of us there on our side: Frank Muir, Denis Norden and Sid Colin for the Kavanagh agency, and Ray [Galton], myself, Eric [Sykes] and Spike [Milligan] for ALS.

There were no real doubts, once these two camps of comedy writers found themselves gathered together, where this meeting was going to go. 'Between the two of us,' Simpson noted, 'we must have represented, at that time, getting on for fifty of the top comedy writers in the country'. As his partner Ray Galton would clarify: 'And if you had the top fifty, you had all of the top comedy writers in the country.'

Before any actual discussions began, however, the writers were treated to a flip-chart presentation by Harry Alan Towers - basically a reprise of the standard talk he had been giving in recent months to a wide range of movers and shakers all over the country - about how the ITV network was going to operate, what kind and quantity of programmes they would be looking to import and make, what sort of targets they were aiming to reach, and what size of profits they were expecting to make.

Once this preamble (which was heckled throughout by Milligan) was over, it was time, as Simpson would recall, for the proposal:

The idea was that we - the two agencies - would sign a service agreement to service ATV with all of their comedy. Exclusively. So that was the idea: they would have had all of the top comedy writers working for ATV, and the BBC would have had to make do with whomever was left. Which, quite frankly, was no one of any note.

It is fair to say that the offer, at least initially, elicited diverse reactions among its audience. Neither Spike Milligan nor Eric Sykes, by disposition, was attracted by any notion of restriction and confinement - their main motivation in setting up ALS, after all, had been to protect their independence (and they would break with their fellow directors just over a decade later when they disagreed with the decision to allow ALS to be swallowed up by the much bigger Robert Stigwood Organisation).

Frank Muir and Denis Norden, meanwhile, were feeling rather more pragmatic, but, given their current success at the BBC, were probably fairly wary of burning their bridges for what might turn out, for all anyone really knew, to be a brief bout of boom and bust. Galton and Simpson, as a younger, and considerably less financially secure, writing partnership, were somewhat more open to the general idea. Sid Colin, meanwhile, as someone who was used to switching between solo and group projects for a wide range of employers, was probably uneasy about the prospect of exclusivity but still curious about just how big the sum was likely to be.

Before any further details - and specific money matters - were put on the table, the ITV representatives suggested breaking for refreshments while the agency representatives mulled over the basic idea. Tea, beer and sandwiches were thus served while the executives chatted away idly to each other at one end of the room and the writers huddled together at the other.

'Now that made for quite an amusing contrast,' Eric Sykes would reflect. 'There was them, all up at that end, doing that very polite mumbling and nodding thing at each other but really just wondering what was going to happen. And here was us, in this other corner, looking very conspiratorial, with Spike growing progressively more animated, Frank and Denis getting nearer and nearer to each other, I think I got up and walked about for a bit, and there were all sorts of intriguing noise and action going on.'

Eventually, after much slow tea-sipping and staring at the walls and floor amongst the bosses, and much agitated semi-whispering, arm-waving, groaning, giggling and back-patting amongst the writers, the meeting was deemed ready to resume. This was when the train switched tracks.

Towers, on behalf of his colleagues, was planning, somewhat in the style of a game show host, to execute the big reveal and announce the financial sum on offer. The two agencies, however, had decided during their huddle to seize the initiative, having already agreed among themselves - Simpson would recall - on their own basic terms:

I can't remember who - it could have been Frank or Denis or Sid - said, 'Right, for a consideration of five thousand pounds for each of the directors here - that's a total of thirty-five thousand - we will undertake to service the agreement'.

That was the bullet slotted into the chamber. This was the sliding doors moment.

Shun the deal, and the world of British comedy would carry on evolving in much the way that it was doing. Shake hands, and, all of a sudden, there would be no more Hancock's Half Hour, no more The Goon Show nor Take It From Here, and, who knows, the next great era of radio and TV comedy, with the likes of That Was The Week That Was, Comedy Playhouse, Sykes, Beyond Our Ken, The Navy Lark, Round The Horne, Steptoe And Son, The Frankie Howerd Show, The Frost Report, Till Death Us Do Part, Q5 and so many other weird and wonderful gems, would never be allowed to happen - at least not in the style, and with the substance, and to the extent, that it actually did.

All that the commercial TV bosses had to do, to blow the BBC out of the water, was to pull that trigger.

The men from ITV, however, couldn't do it. The safety catch went back on. As Alan Simpson would put it, after starting out by banking on the writers' supposed greed, they suddenly seemed repelled by the apparent show of it:

Harry Alan Towers said, 'Oh, I'm not going to be held up to blackmail! Thirty-five thousand? It's absolutely ridiculous!!!' Then Leslie Grade said, 'I can get scripts at five pound a time!' And that was it - the whole meeting broke up in acrimony.

Eric Sykes, when looking back, would seem quite content that he and his colleagues had ('semi-deliberately,' in his opinion) priced themselves out of a dubious-sounding deal. Alan Simpson, on the other hand, would still sound slightly disappointed, or at least a little bemused, that the commercial operators had lacked the courage of their convictions:

I mean, even in those days, thirty-five grand wasn't a lot of money. Not for what was on offer. Not for what they would have been getting in return! They could have decimated the BBC if they had done that deal. Absolutely decimated it.

'ITV may have had a licence to print money,' Ray Galton would later reflect on this incident, 'but they certainly weren't prepared to spend it!'

The ITV men, red-faced and furious, left the building hurriedly and returned to their respective offices. The agency men, mainly smiling and joking, ambled off to a local pub. Only Harry Alan Towers, the fixer who had flopped, remained behind in the meeting room, suddenly feeling unnervingly alone.

The future would be the one that we lived through. ATV, along with the other ITV companies, would go ahead and make some popular comedy and (especially) variety programmes all of their own - although it would do so without Harry Alan Towers, who was 'encouraged' to resign from the board at the end of 1955. As he would put it in his memoir, Mr Towers Of London: 'My fellow directors at ATV had gotten together, behind my back, and decided to diminish my responsibilities. On my highway to success, I had ridden too hard and had antagonised many of my colleagues and peers. [...] On top of that, I had failed to control the finances of the many companies in which I was involved and they were in a precarious position. In short, I was in a heck of a mess and had only myself to blame.'

The BBC, in turn, would remain the main base of British comedy for the foreseeable future. It continued to produce its existing successes, while providing the time, patience and patronage required to nurture new adventures in humour that would intrigue and surprise and stretch rather than just pander to pre-existing preferences.

The writers, meanwhile, would generally stay as free agents, and go on to benefit, exactly as they had expected, from the expansion of an increasingly lucrative market. As Alan Simpson later reflected:

It was through the arrival of ITV that fees were soon doubled for many writers. They certainly were for us. We were in a situation where Tony Hancock had a contract with [the impresario and now ITV producer] Jack Hylton to do some more stage work, and he wanted to get out of it, so Jack Hylton said, 'All right, then, do a couple of television series for me, for ATV, and we'll call it quits'. And by that time we were under an exclusive contract with the BBC, and the BBC said, 'No, you can't write it'. So we said, 'It's short-sighted, really, because we've got the BBC series coming, and it's in all our best interests that the shows are successful'. They said, 'Yes, good point'. So then they said, 'Okay, you can write it, but you can't get credit'. So we wrote two or three of these Jack Hylton shows, without credit, but we got double our BBC fee. So when we went back to the BBC to write for them we said, 'Oh, incidentally, ITV were paying us this much...' So Beryl [Vertue] doubled our money.

Those who would benefit most of all from this bullet being missed, however, were the audiences. It was they who ended up with the best of both worlds - a much more attentive and competitive BBC, and a whole new range of interesting additional resources.

How ironic it was, therefore, that such progress was almost stymied, to an extent, by some of the very people who were supposed to be pushing it through.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreSpike & Co.

This is the story of how four people, grouped together inside a set of offices five floors above a greengrocer's shop on Shepherd's Bush Green in West London, launched a golden age of British comedy.

On any weekday morning, if you dared to clamber over the crates of fruit and veg outside on the pavement, and climb the five flights of stairs to Associated London Scripts, you would find Spike Milligan, Eric Sykes, Ray Galton & Alan Simpson, shaping the latest shows, swapping the odd story and searching for a funnier line.

Together, this eclectic bunch, and their bizarre office block, were responsible for a golden age in British comedy, which included The Goons, Hancock's Half Hour, Sykes, Steptoe And Son, Comedy Playhouse, The Frankie Howerd Show, Beyond Our Ken, Round The Horne, The Arthur Haynes Show, The Army Game, Bootsie & Snudge, That Was The Week That Was, and Till Death Us Do Part.

Spike & Co. is their incredible story.

First released: Thursday 19th October 2006

- Published: Wednesday 25th October 2006

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Minutes: 137

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 448

- Catalogue: 9780340898086

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 9th August 2007

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 448

- Catalogue: 9780340898109

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Thursday 5th October 2006

- Distributor: Hodder & Stoughton

- Discs: 2

- Catalogue: 9781844563111

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Harry Alan Towers - Mr. Towers Of London: A Life In Show Business

Here, in his own words, are the illustrious adventures of Harry Alan Towers, rascal and raconteur, a notorious figure in the world of cinema of whom it was said he could go into any production office in the world and walk out with a movie deal.

After establishing himself in 1940s radio with The Lives of Harry Lime and The Black Museum, both starring Orson Welles, Towers produced more than 100 feature films all around the world. He worked in 40 countries from Austria to Zimbabwe, starring the likes of Michael Caine, Christopher Lee, Jack Palance, Klaus Kinski and many more.

A lifelong lover of literature, he brought to the screen the works of authors as revered as H. G. Wells, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie - and as reviled as the Marquis De Sade and Leopold Von Sacher-Masoch. And as a lifelong lover of women, he made friends and stars, national news and international scandals.

First published: Friday 1st February 2013

- Publisher: BearManor Media

- Pages: 174

- Catalogue: 9781593932350

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: BearManor Media

- Download: 1.11mb

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.