The Great Tiddlywinks Caper: Goons, Royals and Cambridge games

Some things in the history of comedy are just so odd that it would be perverse to project on to them any kind of preamble. It is best simply to go straight to the point and say what the story is actually about.

So here goes: this story is about the time when The Royal Family asked The Goons to represent them in a game of tiddlywinks against the University of Cambridge.

This strange little tale (whose origins date back to sixty-seven years ago this month) has settled so snugly into myth over the past few decades that, when one attempts to draw all the various details back together, one finds it is not so much a case that, as someone famously once put it, 'recollections may vary,' but more that recollections are largely non-existent. What follows, therefore, is as much of the truth that, with a nod as well as a wink, we can, so far, gather together and trust.

To set the scene, let's begin by explaining things from the vantage point of tiddlywinks. The activity had actually been around in various forms and fashions for centuries (Stone Age men, it is thought by some, may have essayed an occasional game while chipping flints), before advancing during the Industrial Revolution (when carpets, by now considered essential to playing, first became mass-produced) and then being trademarked and trumpeted in the late Victorian era, but had only become formalised as an actual 'sport' in January of 1955 - and only then, it seems, because of the ineptitude of certain Cambridge undergraduates at more traditional competitive activities.

These students were craving the chance to win the right to wear their university's precious light blue shirt against Oxford in a proper varsity contest, but had so far been found wanting by each and every team game for which they had been trialled - cricket, rugby, football, rowing, hockey, lawn tennis, table tennis, you name it, these characters had failed at it.

Deeply frustrated by their lack of prowess at all of these conventional athletic pursuits, but still determined to represent their university in an official competitive capacity, they thus came to the cunning conclusion that their best chance to do so would be to devise their own game and then proceed to govern it, play it and dominate it. The result was the founding of Cambridge's - and the country's - very first student organisation dedicated solely to the noble sport of tiddlywinks: the Cambridge University Tiddlywinks Club (CUTwC).

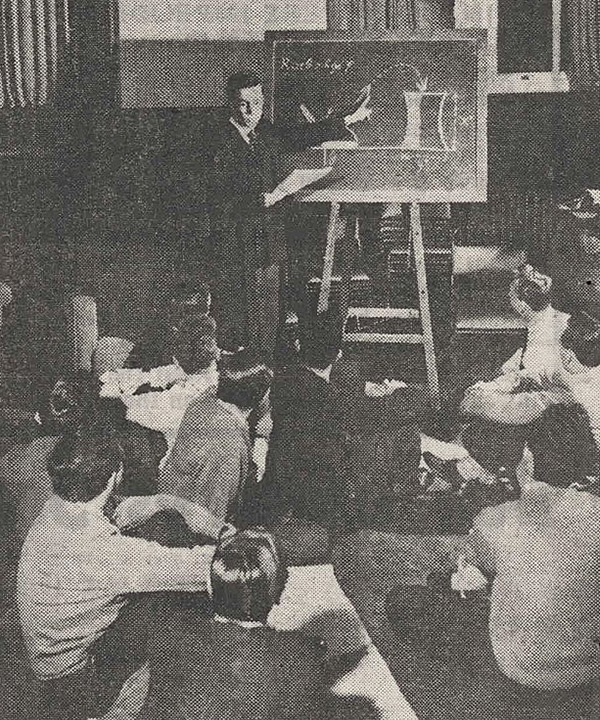

Once the undergraduates in question had subjected themselves to their own less-than-rigorous vetting process, and passed each other with flying colours, they proceeded to design their own tie (a dark background with light blue pots and descendent gold winks), find the appropriate mats (after first sampling all of the small carpets in stock at the local department store, Eaden Lilley's, they ended up settling on a decidedly expensive set made of Berkshire needle loom supplied by Peter Shepherd & Co of Reading), write their own rule book and cultivate their own clique. It was thus not long before - blackboard up, chalk poised - such technical terms as 'squidging' (flipping a wink), 'squopping' (flipping a wink so that it comes to land on top of one's opponent's wink) and 'scrunging' (bouncing a wink out of the pot) were suddenly being bandied about amongst the nascent cognoscenti with an intimidating air of authority.

Two senior members of this brand-new club - Mr Lawford Howells and Mr Bill Steen, both of Christ's College - then snapped into action and, showing typically boundless youthful ambition, sent out a mass of invitations by land and air mail for a proposed First World Tiddlywinks Congress (a letter was also dispatched - never let it be said that a Cambridge undergraduate ever knowingly overlooks an opportunity to network - to the Speaker of the House of Commons). The agenda of this would-be momentous meeting was to include a discussion of the design of a suitable British-based national stadium ('drawings would be appreciated'); the possibility of regular international tournaments; the advisability of approaching the Olympic Committee with a view to adding tiddlywinks to the summer games; and, tantalisingly, 'Any other comments'.

The brave new age of Cambridge tiddlywinks was thus awake and stretching. The much-coveted light blue shirt was beckoning.

Now let's turn to look at the matter from the rather more oblique angle of The Goons. A fixture on BBC radio since 1951, and by the mid-Fifties firmly established as a comedy phenomenon and national institution, it had always been essentially and refreshingly irreverent, never missing a chance to cock a snook at any and every symbol of authority - the wireless and tireless revenge of a wartime generation well and truly sick and tired of being shouted at and ordered about by those claiming to be their superiors.

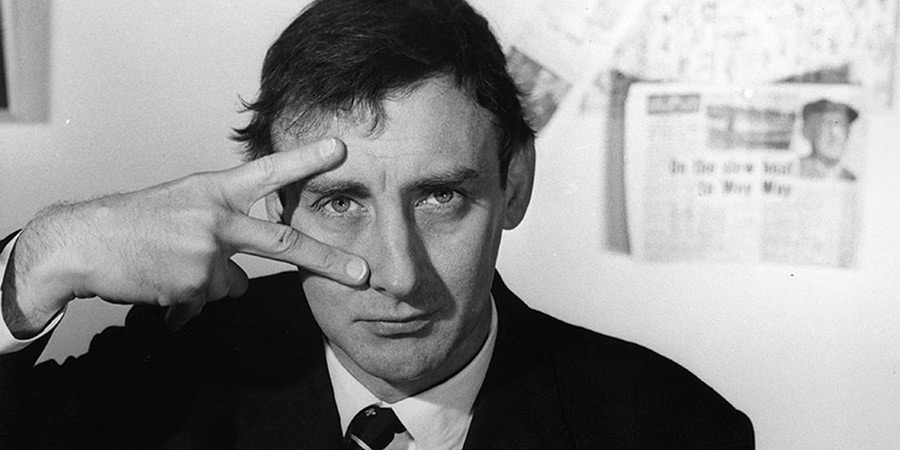

When it came to their attitude to the monarchy, however, the individual Goons were somewhat muddled. Spike Milligan, for example, seemed as skittish as a squirrel on the subject. An egalitarian elitist, an intolerant liberal, a sceptical Catholic, a gregarious misanthrope, a gullible man full of cunning - that was Milligan in a nut shell, and Spike in a nut case, and, as far as his position on the Crown was concerned, it rendered him what might most accurately be described as a republican royalist.

Harry Secombe, meanwhile, had grown-up as a church-going grammar school boy quite conservative at heart, but, having endured more than enough rigid regimentation in the course of his own military travails, he was still far more likely to goose than grovel when invited to mix with the so-called great and good. The painfully insecure but ferociously aspirational Peter Sellers, on the other hand, was even in those early days so dazzled by the shiny surfaces of social ascendency that his nose seemed propelled towards the higher-born fundaments with all the power and precision of a heat-seeking missile.

If the Royals came calling, therefore, the Goons would at least be curious, and, to varying extents, deep down, rather flattered. While they were busy rattling the cages of those who were occupying the upper echelons of the country's class tower, they retained a certain reverence for, or at least sympathy with, those who were teetering right at the very top.

So how did tiddlywinks, the Goons and the Royal Family ever come together? It was, to use a piece of current corporate speak, a case of synergistic opportunism.

The Royal Family, or, more specifically, Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, was one of those who was looking to promote a cause. The cause, in his case, was the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA).

He had become president of the NPFA in 1947, and, with his trademark Albertine spirit, had spent the best part of the next decade doing his best to reinvigorate the organisation in the challenging post-war era. Charged with the task of promoting the aim of creating and maintaining accessible spaces for play, sports and recreation in British cities and towns, he was actively looking for new ways and means of bringing the NPFA to the attention of a new generation.

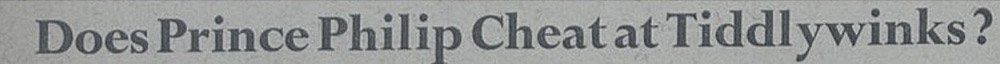

The seed of a similar marketing strategy was growing inside the head of the new titan of tiddlywinks. A nineteen-year-old undergraduate named Peter Downes, the honorary secretary of the CUTwC (quite why the club felt the need, or found the room, for an 'honorary' secretary at this early stage in its development is something of a mystery), had recently read an article in The Spectator magazine (dated 18th October 1957) entitled 'Does Prince Philip Cheat at Tiddlywinks?'

Written by Strix (the nom de plume of a waspishly witty columnist called Peter Fleming), the article had merely been a satirical means of defending the Royal Family from a 'new vogue for cashing in on iconoclasm,' which was particularly unfair on them, Strix argued, because of their conventional reluctance to respond to 'the frivolity of the criticisms' and reveal 'their lack of substance'.

The accusation about cheating at tiddlywinks was simply an eye-catching way of luring the reader in. The point was that, to mix and muddle the metaphor, whatever claim might be made, it was aimed at an open goal.

The precociously enterprising Downes seized on this playfully provocative piece of nonsense and proceeded to hatch a plan. If he could draw the Duke of Edinburgh into the world of Cambridge tiddlywinks, he reasoned, the consequent publicity would push the new sport far beyond the confines of academia and potentially deep into the popular consciousness. He therefore took a sheet of Christ's College-headed notepaper, typed a generally polite but slightly cheeky request, challenging the Prince to a cheat-free game of tiddlywinks, and sent it off to Buckingham Palace, along with several copies forwarded to the national press.

Prince Philip, when he read the letter, realised that, rather than either ignoring it or simply sending back a succinct reply, he could exploit it for his own publicity purposes. He thus first had one of his secretaries sound-out an initially startled Spike Milligan as to the possibility of him representing the Royal Family in this ruse (Philip, after all, was not only a contemporary but also a genuine fan), and then, when that invitation was accepted, he dictated a response to be sent to Downes directly, accepting the challenge in his capacity of the president of the NPFA.

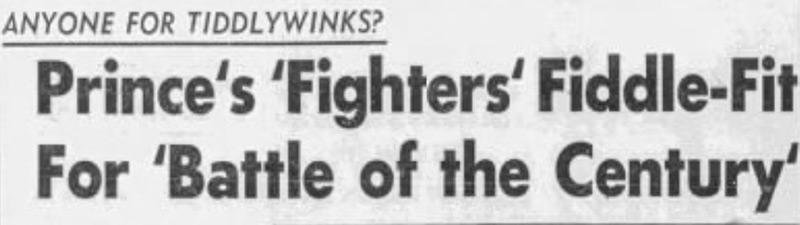

Both parties duly leaked the exchange via their respective contacts, and, taking the bait, the news was promptly announced in the media on 16th November 1957, with a report planted in the then-widely-read William Hickey gossip column of The Daily Express. It was claimed there that, in response to an accusation by Downes and several other undergraduates that Philip 'sometimes cheats at tiddledywinks,' he had challenged them to a 'fight to the last tiddly'.

Revealing that Spike Milligan had been appointed the captain of Philip's team, the comic himself was quoted as saying: 'We shall certainly take the pants off the Light Blues. [...] I have thrown down the gauntlet in no uncertain fashion. I bought a 17s 9d leather glove, real hide. It has gone by registered post to the captain of the Cambridge team. I am told Cambridge take their tiddly-winks seriously. But we shall win - with ease'.

On 20th November, the University's tiddlywink entourage responded excitedly to the challenge via a handwritten scroll, tied up with a light blue ribbon, sent up on the King's Cross train and delivered by taxi to Milligan's offices, situated in those days at Cumberland House on Kensington High Street, at the comedy writers' co-operative known as Associated London Scripts:

Hear Ye, Spike Milligan.

Be it known, mate, that we Cambridge tiddly-winks team taketh up ye gauntlet and will join battle with ye Royal Champion Goons early in ye New Year.

Preparations for the event were rather more intensive on the academic side than they were on the comedy side. In Cambridge, it was announced that the president of the tiddlywinks club would be overseeing a number of trials during the course of the next three months. After trying and failing to enlist the help of certain celebrities to round up a rival team of novice winkers - television's original 'Mr Nasty', Gilbert Harding, informed them brusquely that he had given up the game 'at the onset of adolescence,' while the former footballer and veteran cricketer Denis Compton declined more politely on the grounds that he feared his knee wouldn't stand the strain 'of all that kneeling' - they managed to make a start with a match against the nurses of Addenbrooke's Hospital, in order to select the most white-hot winkers of the lot.

Various shiny-haired and bespectacled young men were thus working very hard to impress, wiggling their thumbs as if undergoing an essential winking workout, examining pots, discs and mats like bespoke technical equipment, and loudly talking tactics in the hope of being overheard by a VIP: 'My thesis,' one of them was reported as shouting (presumably just before someone else hit him), 'is that in squidging a wink into the pot R equals P cos A plus S: R being the normal reaction of the isotropic compressible medium, or carpet, on which the game is played; P being the applied force; A the angle between the wink and the squidger and S the steen factor...'

Behind these alpha geeks hovered the beta geeks, hands in pockets, jangling their change and nodding intently as the waffle warbled on. This, all of them agreed, was a very serious business indeed.

Up in London, meanwhile, Spike Milligan's considerably more leisurely recruitment drive was restricted to whomever happened to be around in the offices at Associated London Scripts on the morning he made a perfunctory attempt to drum up a bit of support. Popping his head meekly around each door, he elicited responses that ranged from the dismissive ('If it's not golf,' Eric Sykes muttered without raising his head from his half-scribbled script, 'I'm not interested') to the whimsical ('I only know the Burmese version,' Ray Galton protested from his usual resting place flat-out on the carpet, claiming that the Burmese version involved teams on elephants who rushed their opponents, wielding rosewood bats, and attempted to toss them into a large vat of porridge). 'I'll leave it with you,' Milligan shouted down the corridor, with a sigh, to no one in particular, and then returned back to the security of his typewriter.

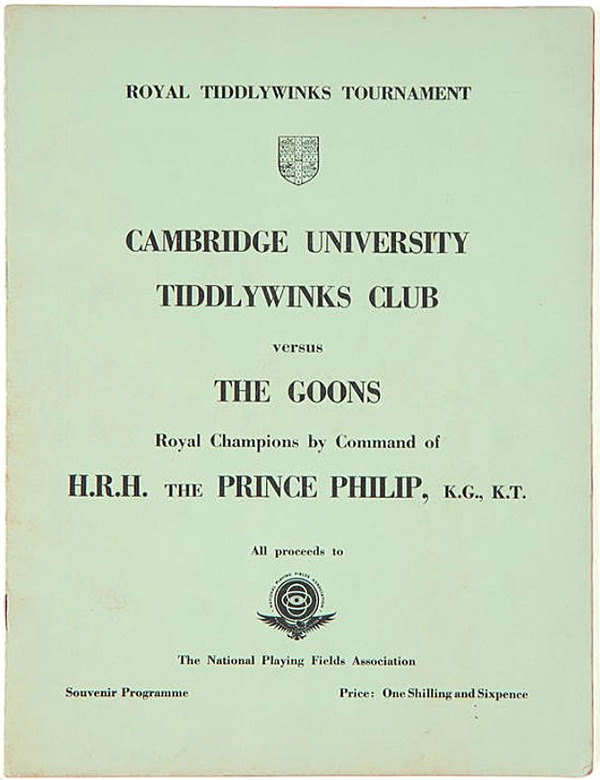

Those who were keenest about the forthcoming competition, however, were already busy cranking up the coverage. Roy Harry, the appeals secretary of the NPFA, did his bit to promote the occasion by announcing: 'This is turning out to be a very serious affair indeed. I have been in touch with the secretary of the Cambridge club, Mr Peter Downes, and I have here a full set of rules. Each game will last eighteen minutes, starting with a pistol and ending with the ringing of a bell'. It was all set to be, Harry and Downes agreed, one of the most distinctive, distinguished and memorable sporting contests of the season.

The national newspapers, once nudged enough by Messrs Harry and Downes, were certainly pleased to give the event plenty more free publicity. One report, dated 4th February, claimed excitedly that 'many of the most enthusiastic tiddlywink men for miles around will be travelling into Cambridge for the match, and parties will be travelling north from London'. Television previews followed, with a variety of shivering homburg-hatted, tweed-jacketed hacks (hugely grateful for something to discuss after several planned events had been postponed due to the current inclement weather) providing brief 'light-hearted' coverage of the preparations for Sportsview and similar shows.

The big day finally arrived on the morning of Saturday 1st March 1958 in what was known as 'The Large Hall' of the Guildhall building in Cambridge town centre, situated by the market square, just a mortar board's toss or two away from King's College Chapel and Auntie's Tea Shop. Six-hundred seats were set up (priced five shillings for matside or three shillings and sixpence for gallery), for paying members of the public to settle down on and watch the action unfold, while overcoated representatives from Eaden Lilley's brought in the playing tables - which, having quickly learned their own trick or two, they were now selling as 'tiddlywinks tables' - and placed them into position.

As had been promised, it proved to be quite a spectacular event. There were queues around the block - Cambridge on a Saturday was always bustling with hordes of shoppers, but all of the interest in this particular occasion had attracted cars, trains and busloads of additional visitors, and there were also camera crews (including one from America's CBS network, as well as BBC TV, ITV, Pathe News and British Movietone) and print news teams (from all the nationals and quite a view provincials), and packs of police officers, too - and several scuffles broke out while touts haggled with punters (a tranche of forged tickets - bearing the wrong date - had been discovered) as wave after wave of excited Goon fans - ranging from young children to senior citizens, many of them mimicking the voices of Bluebottle, Bloodnok and Eccles - struggled to squeeze themselves (both legally and illegally) inside the grand old building.

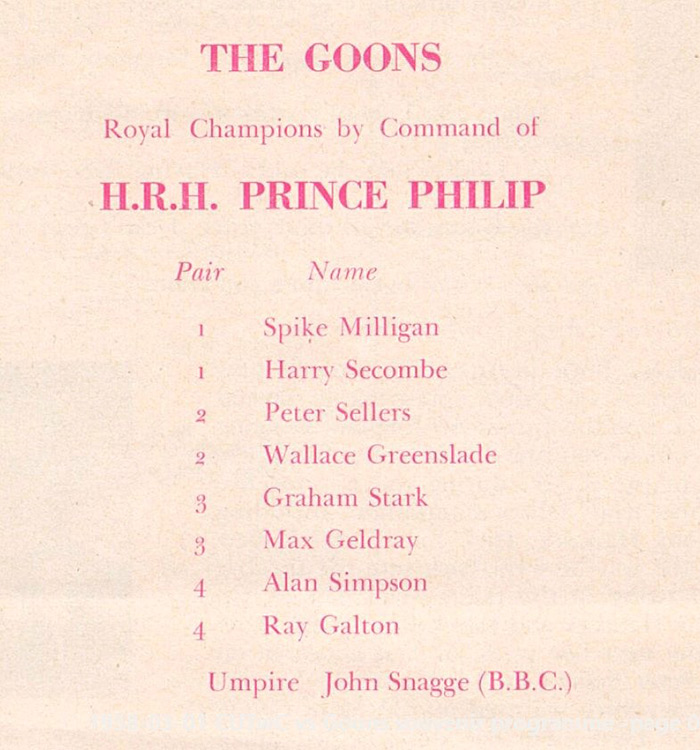

Each team, waiting patiently within (they had all arrived in the basement via a secret subterranean passage beneath what in those days was the public library around the corner in Wheeler Street), was composed of eight members. The Royal team consisted of Milligan, Sellers and Secombe (the latter of whom having flown in at the last minute from his pantomime in Coventry via a helicopter loaned by the Cambridge-based company of Fison's Pest Control), plus Goon Show associates; the announcer Wallace Greenslade and harmonica-player Max Geldray, Sellers' unshakeable sidekick Graham Stark (a hurried replacement for the advertised but otherwise-engaged Ray Ellington), and Milligan's fellow writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, with the BBC's sober-voiced news announcer John Snagge co-opted as their umpire.

The Cambridge team, led by David Arundale (a twenty-four-year-old graduate student researching Chemical Engineering), was made up of a selection of rather nervous-looking youngsters drawn from Christ's, Caius, St. Catharine's and Pembroke colleges. The St John's College alumnus and Olympic athlete Christopher Brasher was acting as their own chosen umpire.

All members of the University team were resplendent in smart dinner jackets and bow-ties. The Goons and their colleagues sported orange, yellow and black-coloured school caps, long canary-yellow nightshirts and 'Royal' tiddlywinks ties.

Shortly before the proceedings began at 11.03am, John Snagge stood before the audience and, with his usual sombre expression, read out a message from the Duke of Edinburgh:

Please give my best wishes to the two teams taking part in the great contest, but try if you can to do it in such a way that you convey that I wish the Cambridge team to lose and my incomparable champions to win a resounding and stereophonic victory.

At one time I had hoped to join my champions, but unfortunately, while practising secretly, I pulled an important muscle on the second or tiddly joint of my winking finger. This is naturally very disappointing, but at least it gives my side a very much better chance to win.

Wink up. Fiddle the game. And may the Goons side win.

-PHILIP.

Christoper Brasher, with a suitably melodramatic flourish, then fired his cap pistol to signal that the contest had started. What followed was the kind of 'mirthful mayhem' that most people had been expecting.

'The comedians made up for their lack of tiddlywink skill with a humorous patter and clowning performance which kept the large audience surrounding the four mats highly entertained,' reported one observer.

The proceedings took about an hour-and-twenty minutes to complete. The result, much to the audible disappointment of the majority of the spectators, was a comfortable win for the CUTwC by 120-and-a-half points to 50-and-a-half.

Mrs B.J.S. White, the Conservative Mayoress of Cambridge, then took to the stage to present David Arundale, the Cambridge captain, with a commemorative pewter tankard. Somewhat bizarrely, she also handed out a mounted and engraved plastic 'model chamois' (specially made for the occasion by one of the sponsors, the drinks manufacturer Showerings of Shepton Mallet) to each of Milligan's losing team.

The event came to an end after Harry Secombe (complaining that 'we tiddled when we should have winked') sang - to the tune of Men of Harlech - a specially-composed tiddlywinks anthem:

Other nations are before us,

With their 'Sputniks' and 'Explorers'.

What can confidence restore us?

NAUGHT BUT TIDDLYWINKS.On the fields of Eton

Former foes were beaten.

But today

All patriots play,

This sport which needs such grit and concentration.

Through the game of skill and power

England knows her finest hour,

And her stronghold, shield and tower,

MUST BE TIDDLYWINKS!!

The triumphant captain, David Arundale, strode over and took centre stage to call for 'three cheers for the Duke'. Clearly unencumbered by the draining weight of callow humility, Arundale then proceeded, in the manner that has always so endeared students to the general public, to 'entertain' the assembled professional comedy writers with his own, quite lengthy, humorous victory speech, to which they responded with short but still generous applause.

With the proceedings now declared over, the hundreds of spectators stood up and started to disperse in multiple directions. Secombe said his farewells and then raced off in a taxi down the nearby Grange Road to St John's College's playing fields, where the Fison's helicopter was waiting to fly him back to Coventry for the next matinee performance of Puss in Boots. All of the other participants wandered off a short distance away for a long and leisurely lunch at the Lion Hotel in Petty Cury, where the comedians slurped champagne and the students supped on their official 'training drink' of Babycham.

During the festivities, Milligan slipped away to the reception desk to dictate a telegram to Prince Philip: 'PREPARE TO ABANDON SHIP, [SIGNED] ROYAL CHAMPION'.

Adding to the lingering sense of surrealism that had surrounded the occasion, the BBC then provided sound-only highlights of the contest later that day, courtesy of a predictably bubbly Brian Johnston, in the 'kaleidoscope of words and music' that was the Saturday Night On The Light programme. Newspaper reports would follow, not only throughout the UK but also in many other countries across the world.

Once the day was over, the various parties departed, looking somewhat tired and emotional, and it would not be long before those who had witnessed the weirdness of it all started to think of it as akin to a strange sort of dream. The way that it was recalled by those who took part, however, would very much be coloured by their respective responses to what it had been deemed to have achieved.

For the Royals, the memory could hardly have been sunnier. The event had managed to raise (adding to the receipts an additional filming fee from the BBC and a one-hundred guineas donation from Showerings) an estimated £225 for the National Playing Fields Association, which would be multiple thousands of pounds in today's money, as well as generating the most widespread publicity (international rather than merely national) the organisation had probably ever enjoyed. From Prince Philip's point of view, therefore, it was clearly a case of mission accomplished.

It was nothing like that happy fact as far as the members of Cambridge's tiddlywinks club were concerned. No sooner had they finished jumping up and down and hugging each other in celebration on that momentous first day of March, a serpent started to slither its way through the long fenland grass and straight into their tiddlywink Eden.

Their own rather fanciful claim to have become 'world champions' on the strength of their triumph over the Royal comedy troupe came crashing down just a couple of months later, when (following a warm-up session against a scratch team of West End women dancers - organised by The Daily Mirror journalist Noel Whitcomb - called 'Whitcomb's Winkers') they lost their very first match against Oxford (hosted in the Forum Ballroom on the latter city's high street) in highly contentious circumstances. Unable to agree even on the name of the game - the Oxford students, sporting mischievous smirks, insisted on calling it 'tiddlewinks' - the two teams argued from start to finish, with some competitors even coming close to exchanging blows, and the embittered Cantabrigians eventually departed still protesting that, as far as they were concerned, it had merely been an 'experimental' meeting, run without proper rules, and the result therefore had no bearing on their continuing claim to rule the entire world.

They did, in their defiance, go on to hold their long-promised international congress back in Cambridge, at Christ's College, where a package of procedural practices was formally agreed and the first official English Tiddlywinks Association was established. The teasing from their Oxford rivals, however, would continue for some time, and they were left to feel that the joke, which had started out so amusingly, had ended up rebounding on to themselves.

As for the Goons, it had been more of a mixed experience. Harry Secombe's hapless publicity agent, George Bartram (whom he shared with Morecambe & Wise), ended up being fined £3 and had his driving licence endorsed after being booked for speeding, having incurred the wrath of the Coventry constabulary when racing to get his client to Baginton airport for the helicopter ride to Cambridge (Secombe was not best pleased when Bartram suggested that he help out with the expenses). Peter Sellers, on the other hand, had loved every minute of it, having been pictured beaming with pride as he listened to Prince Philip's message of support, and evidently regarded his contribution as one more stepping stone in his move to be mates with the members of the Monarchy.

Spike Milligan, meanwhile, was, as usual after rubbing shoulders with any members of the Establishment, unsure whether to celebrate or shower. Ever the pragmatist, however, he did get a Goon Show script out of the venture: Tiddlywinks (Series 8, Episode 24), first broadcast, one week on from the contest, on Monday 10th March 1958.

It seemed to be quite a cathartic exercise, as the storyline flirted with the facts ('Cambridge should never have beaten us,' Neddy moans, before becoming even more enraged upon hearing that no message of consolation has come in from the Palace. 'Coh! He's a lot of good, innee? My life! There we were, dressed up like idiots, popping little buttons into a cup - and still no signs of a knighthood!) before flying off into fantasy.

Intent on revenge, Neddy challenges Cambridge to a leaping contest, armed - or rather footed - with the devious secret weapon of rocket-propelled boots. When Bloodnok snitches on Seagoon to the Cambridge Leaping Team, Neddy flees to Wales and becomes an outlaw, holding up travellers for their own tiddlywink treasures.

He then devises a devilish plan to attack Trinity College, Cambridge, and steal the university team's entire supply of their premium winks. Eventually, however, John Snagge, still identifying himself as the umpire, reappears, judges Neddy's conduct to be utterly unbecoming of a supposed Royal Champion, and insists that he hand back all of his winks. To further atone for his nefarious stratagems, Seagoon is ordered to raise his right leg, face east and sing the new tiddlywinks anthem.

Having thus exorcised whatever demons were dogging him, Milligan would go on as usual, mocking the powers-that-be, and, at least some of the time, having a good laugh as he did so. Times changed, moods moved on, and never again would he and his fellow Goons return to Cambridge (or anywhere else) at the 'command' of the Crown, and many years later, Spike, tipping the wink to a million or two watching on TV, would strike a rather more comfortable pose when he responded to the then-Prince Charles' tribute to him by calling him 'the little grovelling bastard'.

That seemed to bring, belated though it was, a decent sort of balance to the bargain. To rephrase the tiddlywinks anthem: What can confidence restore us? Naught but comic cheek.

Help British comedy by becoming a BCG Supporter. Donate and join us in preserving, amplifying and investing in comedy of all forms, from the grass roots up. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more