The duo you don't know: Jimmy Jewel and Ben Warriss

Before Eric and Ernie, there was Jimmy and Ben. After Eric and Ernie, there was no Jimmy and Ben. It is as if the huge success of the one erased the existence of the other. Without Jewel & Warriss, however, there might not have been a Morecambe & Wise.

Jewel & Warriss were the double act that the young Eric and Ernie aspired to be. They were the northern double act who made the breakthrough to a national audience; they were the ones who won their own show.

When Morecambe and Wise first auditioned in London, in the early 1950s, for the big BBC radio show Variety Bandbox, they were sent back home with the sobering message. 'You sound too much like Jewel & Warriss. Come back in five years.'

'We used to watch Jewel and Warriss and they would do twenty-five minutes and we used to think it was bloody awful,' Eric Morecambe later admitted. 'In fact, they weren't, it was just our envy and jealousy.'

That thought, in itself, ought to make people curious about the double act before Eric and Ernie. They were good enough, and popular enough, to make the other two jealous.

Who, then, were Jewel and Warriss? They were first cousins whose lives were locked together from the moment they emerged into the world. Their respective parents (the mothers were sisters) lived together under the same roof, and they were born, just a few months apart during 1909, in the very same bed - Ben on 29th May and Jimmy on 4th December.

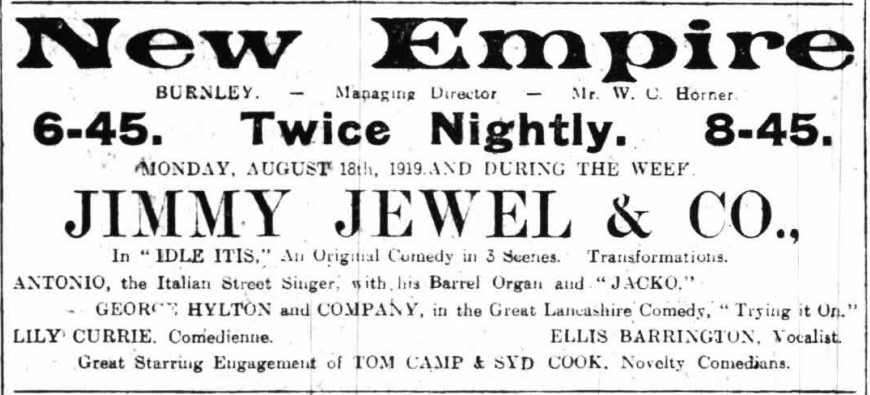

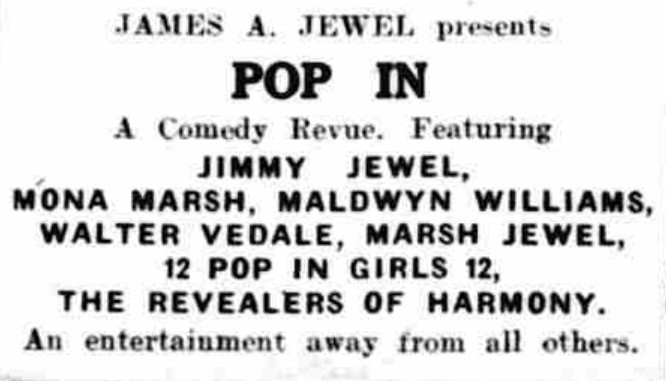

The home that they shared - at 52 Andover Street in Sheffield - was a house full of entertainers. Both of Jimmy's parents had been treading the boards for years: his father, James Marsh, was a comic actor-manager (and master set-designer) who toured the music halls as 'Jimmy Jewel' with his small but popular company of fellow performers; his mother, Gertie Driver, had been a solo singer and dancer before joining her husband's troupe mainly as a backstage manager.

Ben's parents were slightly more conventional - his father Benjamin (who was born in Kingston, Jamaica) was an insurance inspector, while mother Mary worked at home. Both of them, however, had been amateur entertainers in earlier years, and continued to perform whenever possible, often with other members of the family.

Ben was the first of the two boys to step into showbusiness. He was just ten years old, in October 1919, when he made his professional debut at the Hippodrome, Stockport, and the following year he made his first London appearance at the Bedford Theatre in Camden Town. He then became a regular in the Alexander & Mose minstrel show, and subsequently took his act on tour as a solo turn.

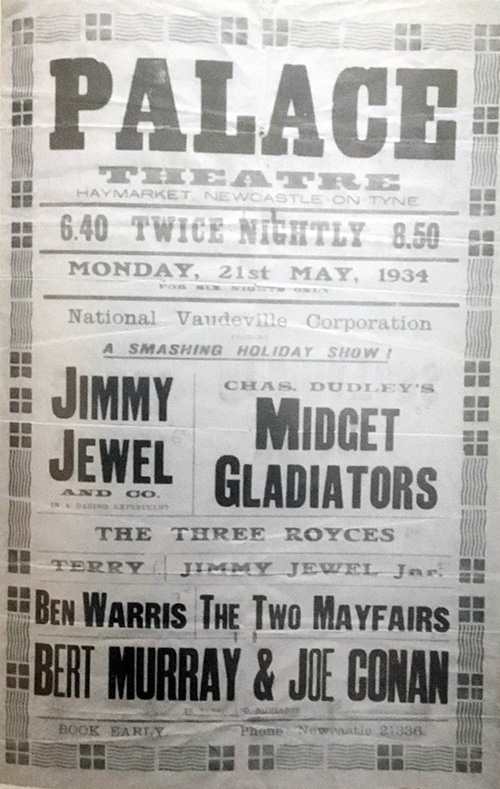

Jimmy was not far behind him. With the encouragement of his parents, he made his own professional début in a walk-on role in one of his family's revues in 1925 (Ben was also in the show) and then, under the stage name of 'Marsh Jewel', developed a solo comedy song-and-dance act that featured impersonations of Maurice Chevalier and Jack Buchanan. As well as continuing to tour, on and off, with his parents' company, he also worked for a spell at the start of the 1930s with Willie Lancet's Midget Troupe and as a solo act on the cinema-variety circuit.

The two young men were brought back together on Monday 21st May 1934 at the Palace Theatre in Newcastle. Although booked there as two separate acts, the scheduled double act from London failed to show up, so they were paid extra to improvise a shared routine ('We pinched every gag we'd ever heard from every comic working,' Warriss would recall, 'and we danced'). It went so well that they agreed to work together permanently as a pair from the autumn of that year onwards, appearing as Jewel and Warriss in a succession of revues produced by John D. Roberton (the father of the future Carry On actor Jack Douglas), and also going on a short tour of Australia.

They returned to Britain to start working on the major Moss Empire circuit, where their act began picking up wide praise for its energy, quick-fire crosstalk and elements of spontaneity. People could see that they were daring to be different.

'There are two comedians in this show who are new to me,' wrote one critic in 1936, 'but Jewel and Warriss, as their names are, will soon, I predict, be well known. Their comedy is unique, and they introduce many fresh ideas in the course of this show. Their work throughout deserves much praise.'

Another, similarly impressed, observer described them as 'an entirely new type of comedy act' who were 'riotously funny'. A third insisted that 'these high-speed funsters' were 'destined for the top of the tree'.

As the positive reviews continued to accumulate, they felt that their fast-growing popularity merited a raise. The management, however, refused to give them one, so they gambled by going out on their own, and attracted such an eye-catchingly enthusiastic reaction (even in Glasgow, where so many English comedians died a death) that Moss soon hired them back at their own terms, which were by now a hefty £100 a week.

A popular act in pantomimes and summer seasons as well as the usual variety bills, Jewel & Warriss were deemed good enough by 1938 to make their West End début at the Holborn Empire under the auspices of Max Miller, and by the start of the next decade they were also getting work on radio. Billed as 'Gems of Comedy', they sparkled in show after show, with the critics celebrating them as 'refreshingly novel comedians' who charmed through their 'spontaneous zest'.

What was their act like at this time? Its dynamics were still clearly modelled on the snappy, fast-talking interplay of American vaudeville partnerships, but with an unusually deft blend of lively physical routines and dialogue-driven sketches.

Jewel played the fool and Warriss the wise guy. Jewel was porkpie-hatted and baggy-panted, a gullible and gormless buffoon, while Warriss was stylishly-attired, sharp-witted and cynical, a domineering dandy.

What made their act more 'modern' than most of their British competitors was its energy, aggression and eagerness to animate and explore its comic ideas. Whereas, say, Flanagan and Allen - probably the UK's most broadly-appealing double act of the day - would stand around and take turns setting up and delivering a series of standard gags, Jewel and Warriss would often start by swapping lines only to shape them into a scenario and swoop straight into a sketch.

They seemed like a double act for a new generation, and a new style of comedy, and the demand for them, as time went on, became increasingly intense. 'They have a stamp about their humour which places it in a class by itself,' declared one critic, and all of those producers who were desperate to sign something 'up-to-date' competed to secure their services.

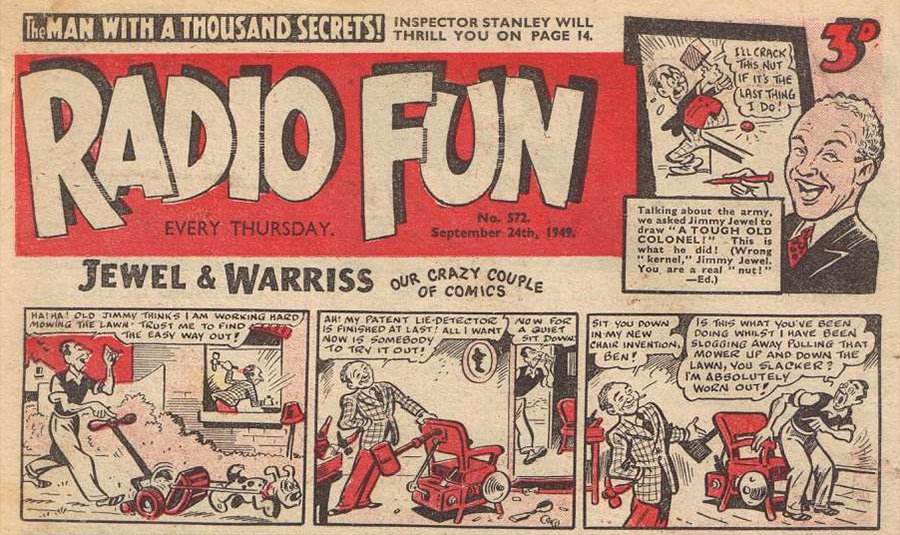

As a consequence, for much of the 1940s and 1950s, Jewel & Warriss were by some distance Britain's busiest comedy double act. They topped the bill at the London Palladium and dominated successive summer seasons and pantomimes at Blackpool. They were picked to appear in no fewer than six Royal Variety Performances between 1942 and 1948, featured in three home-grown movies - Rhythm Serenade (1943), What A Carry On! (1949) and Let's Have A Murder (1950) - and also became fixtures on BBC radio in such popular variety series as Navy Mixture (1946-7). They even had their own cartoon strip in the weekly children's comic Radio Fun.

The BBC awarded them their own radio series, Up The Pole, in 1947. A sort of 'loose' sitcom, broken up by musical interludes, it was something of an achievement for northern comedians - the BBC, while happily broadcasting southern comics to national audiences, tended in those days to restrict most northern comics to its Northern Home Service outlet - and Jewel & Warriss certainly made the most of the national exposure.

Realising that their stage act, with its visual aspects, would have to be adapted carefully for radio performances, they simplified their personalities (with Jimmy becoming more vulnerable and needy, and Ben even more commanding and calculating), brought in some experienced scriptwriters (led by Ronnie Hanbury, who'd already been supplying them with material for some time) and took plenty of guidance from their producer, George Inns. Audibly, the most significant difference was that Jewel (who had quite obviously been influenced recently by some of Sid Field's very popular characterisations, especially - vocally - his camp golfer) now sounded somewhat effeminate. while Warriss (toning down his Yorkshire accent) stayed more or less the same, delivering his lines in his usual strong and snappy tones.

The revisions worked. Up The Pole proved extremely popular, running for four series over the course of the next five years (repeated no fewer than three times every week) and cementing Jewel & Warriss's status as two of the best-known comedy stars in the country.

They also found the time to make a comedy-thriller series called Jimmy And Ben (1950-1) and host a variety series entitled The Forces Radio Show (1953). This fame gained through the airwaves also boosted their stage shows, which were regularly breaking box-office records as fans flocked to see them in the flesh.

American success seemed the next stage in their progress when, in November 1951 (not 61 as some sources suggest), they were chosen to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show. Already one of the biggest entertainment programmes on US network TV (a 'reeeely big shoe', as he tended to pronounce it, regularly attracting an estimated thirty million or more viewers), the programme represented an invaluable springboard to international success.

Described by one critic as 'a man with no perceivable talent', and by another as 'the only dead host of a live show', Sullivan was an improbable TV star. He had the shifty, distracted air of a man who was expecting to be arrested, and moved with all the grace of a badly-handled string puppet. He was, nonetheless, a hugely powerful figure who could make or break careers with his often impetuous and capricious decisions.

Always fearful of offending his sponsors, as well as the more religious sections of his regular audience, he was a notoriously unwelcome presence at rehearsals, repeatedly intervening whenever he saw or heard anything that struck him as potentially problematic. Deeply contradictory, he was known to explode into a torrent of expletives if ever he heard any bad language in an act, and would insist on removing large sections of the script, no matter how close it might be to a recording, once he had decided that something less risky was required instead.

This level of interference and pressure could sometimes crack the composure of the most talented of artists, either wrecking their actual performances or else driving them to storm out before the show had even started. Tommy Cooper, for example, would grow so maddened by his American friend's 'helpful' interventions that he smashed a prop and went off to sob over a Scotch in his dressing room, while Charlie Drake reacted to the first hint of revision to his routine by walking straight out of the studio and never coming back.

The irritations were by no means over even if a performer survived the rehearsal. One of Sullivan's other strange idiosyncrasies as a host was his chronic struggle to remember the right names of his guests. Terry-Thomas heard himself introduced as 'Tommy Tucker', the Italian tenor Sergio Franchi was welcomed as 'Sergio Freako', Shelley Winters was confused with the male stand-up comic Shelley Berman and - sometime in the future - Morecambe & Wise would be disappointed to be introduced to American viewers as 'Morrey, Camby and Wise'.

Not even cue cards could always save Sullivan from such embarrassing linguistic pratfalls. When a floor manager once held up a large sign that included the phrases 'World War I' and 'World War II', he even managed to mess that up by reading them out as 'World War Eye' and 'World War One One'.

Jewel & Warriss, when the call came, knew little of any of this. They simply knew that, if their act went well, they could soon be touring the world, earning a fortune, and making the kind of shows that they most wanted to pursue.

Full of optimism, therefore, they flew off to America (in the company of the up-and-coming young comedian Michael Bentine, who was also booked on the bill) armed with a meticulously-rehearsed ten-minute routine made up from the very best parts of their current stage act. Determined not to leave anything to chance, they continued to perform the material in their hotel room, over and over again, until the cab finally came to take them over to the famous studio in midtown Manhattan.

When they played the routine for Sullivan, however, the problems started arriving. First, he kept asking them - especially Jewel - to tone down their 'Northern English' accent and speak more clearly for Americans. Then he and his associates went through the material, crossing out the slightest line they suspected that someone, somewhere, might construe as having an 'inappropriate' connotation.

Jewel would later reflect on the mounting horror they both felt as they stood there helplessly while 'all our carefully prepared gags were wrecked', and their ten-minute spot shrank to seven, and then six, as the cutting left them 'in a mad whirl of confusion'. Now obliged to perform a much-revised routine whilst trying to speak in a different accent, their timing was compromised and their confidence all but gone. Jewel was physically sick three times simply waiting to go on.

As if to add insult to injury, Sullivan then stunned the pair by introducing them to his audience as 'Jewels and...Walrus!' As Jewel walked past him towards the centre of the stage, Sullivan gripped his arm and growled in his ear, 'Four-and-a-half minutes, you bastard - and no more!'

'Ben was blazing mad,' his partner would remember of the post-show atmosphere. 'If he could have got hold of Sullivan I think he would have killed him.'

While their American adventure had proven a deep disappointment, a breakthrough was made back at home during the same year when they moved into television with the BBCTV series Turn It Up! (1951). A succession of London theatres, including The People's Palace in Mile End Road and the Croydon Empire in Crown Hill, were transformed into temporary TV studios by the producer Michael Mills for these one-hour shows, which combined variety acts introduced by Jewel & Warriss along with their own sketch-based and musical routines (which included such technically imaginative scenarios as fastening a table and chair to a ceiling, strapping Jewel into a seated position, filming him upside down and then getting him to battle against an opened bottle of liquid and various messy items of food; and another routine that saw him get submerged in a see-through tank full of water in order to test a variety of special pens).

They were a huge success - according to some estimates of the time, the series as a whole attained the highest ratings for any light entertainment programme that had so far been measured - and made the double act even more prominent in the country's popular culture. A second series, now called Re-Turn It Up!, followed in 1953, without the guest variety acts but with more comic material from the two stars. The audiences were again huge - by the standards of the time - even though some of the critics now expressed some reservations about the quality of the scripts.

Eager not to lose any momentum, the pair responded to such complaints promptly and decisively by changing their writers. Out went the somewhat exhausted Ronnie Hanbury and his associates, and in came two young up-and-coming crafters of comic material named Dick Hills and Sid Green.

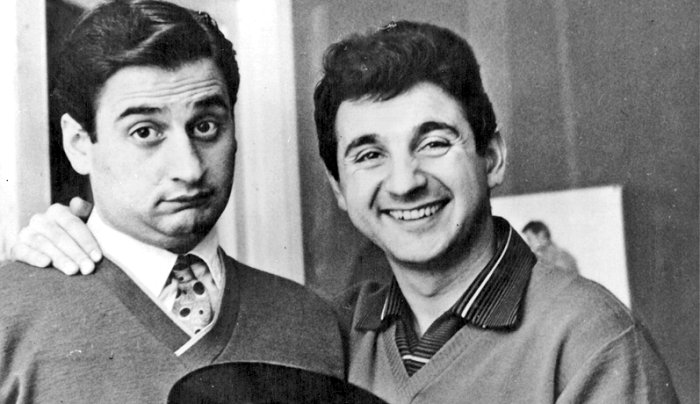

It was an inspired move on the part of Jewel & Warriss. Hills and Green (pictured a decade later with Morecambe & Wise) were fresh, well-educated, self-confident and very ambitious. They had only been working in television for a matter of months, having been taken under the wing of the comedian and actor Dave King, but they were bursting with ideas, and brought a new injection of energy to Jewel and Warriss just when they needed it for a further progression of their career.

Hills and Green started contributing some crosstalk routines for the double act's stage appearances, while they got to know the pair's strengths, and began to develop some possible new programme projects. The first fruit of this process was a series for the BBC called Double Cross (1956), a spy spoof sitcom (inspired by an idea of Jimmy Jewel's about the recent defection of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean to the Soviet Union) that marked the pair's first attempt at carrying a show purely as actors, playing music hall performers-turned-secret agents.

Produced by Ernest Maxin (a future director of Morecambe & Wise), it was one of the most ambitious and expensive TV comedy shows that the BBC had attempted up to this point in its history. Jewel's original (and, for the time, progressive) plan to have the whole show pre-recorded and edited like a movie had been thwarted by the BBC's head of entertainment Ronnie Waldman, who insisted on the core of each episode being filmed live in front of a studio audience, but they did manage to get some sequences specially recorded (including some exterior shots in Paris) by paying for it out of their own pockets.

It was evidence of how determined they were to stretch themselves and create something for the small screen that surprised as well as impressed their audience. Spurred on by Hills and Green, they wanted to show that they were still evolving.

It worked. The critics, who were already tiring of television's over-reliance on filming variety theatre for its popular entertainment, were generally delighted to see two stars who were prepared to push themselves and the medium forward and try something more daring and distinctive.

They were thus widely praised as 'pioneers of television' for 'trying to break new ground'. Even though some reviewers confessed to finding parts of the storyline confusing, and some of the shifts in tone from the comic to the dramatic and back a little jarring, few were inclined to dwell on such negatives, so eager were they to support a show that struck them as pushing TV in the right direction.

The BBC, meanwhile, shaken by the competition from the newly-established commercial TV, was in a hurry to get its two stars back on the screen as quickly as possible. This led to them agreeing, somewhat reluctantly, to return a few months later with a more conventional, but still relatively polished, series (scripted this time by Ronnie Hanbury) called The Jewel And Warriss Show.

They were further distracted from the pursuit of their more ambitious projects by the fact that many producers over at the commercial companies were now so desperate to feature them as guests that a string of lucrative but undemanding engagements duly followed on 'the other side' during the subsequent months. It was never seen as a long-term policy by either of them (they actually had their doubts, it seems, about commercial TV's prospects of survival), but, having seen so many older performers fall on hard times, they were cautious and canny enough to pause while so much cash was coming in.

They were back with Hills and Green, however, to make The Jewel And Warriss Scrapbook for ATV in 1958. A sketch-based series, it disappointed those who were hoping for something of similar quality and care to Double Cross; as one critic put it, too much of the show seemed to rely on 'a backlog of old music hall skits', which were put over 'with the finesse of a road-roller'.

They were probably not quite as bad as that. A compromise kind of project, ATV used the series simply as a ratings weapon, and in that sense it worked; Hills and Green, with Jewel and Warriss, used it as a set of well-funded laboratory sessions in which they could try out a few new ideas, and, to some extent, that worked, too.

The problem, however, was that the BBC - with its greater patience and production proficiency - still represented their best chance of pursuing their prestige projects, but it could no longer compete for them financially. ITV, on the other hand, had no real plan for them, but was prepared to pay handsomely to keep using them.

The consequence was that they stayed at ITV but grew increasingly frustrated. Unable to persuade producers to let them pursue more challenging projects (they and Hills and Green did manage to get commissioned a one-off musical version of the W.A. Darlington play Alf's Button for a Christmas Day special in 1958, but their series ideas kept being rejected), they ended up agreeing to star in a formulaic ABC quiz show called For Love Or Money (1959) - to which they were plainly not suited, and was panned by most critics - and accepted innumerable guest spots on Val Parnell's ATV variety shows.

They were reunited with Hills and Green for a BBC radio series (The Jewel And Warriss Show) in 1958-9, and then again at the start of 1962 for a strange little experiment entitled At Home With Jimmy And Ben. Made for Associated-Rediffusion, this one-off programme took the form of a sketch lasting just fifteen-minutes (ten-minutes without the commercial breaks). Inspired, possibly, by the Sunday Afternoon At Home episode of Hancock's Half Hour, it featured Jimmy and Ben, exhausted after celebrating Christmas and the New Year, with nothing to do but watch television. Whether it was meant as a pilot for a pioneering mini-sitcom, or was merely intended as filler for an awkward slot, is now unknown, but it came and went without any comment.

They followed this later the same year with a conventional sitcom, again for Associated-Rediffusion, called It's A Living. Also featuring Lance Percival, Fanny Carby and Adrienne Posta, the series saw Warriss play the owner of a small general store, with Jewel as his lodger and business partner. The storyline involved the challenges that they were facing from the big modern supermarket situated just across the street.

Written by Fred Robinson (an experienced figure in this area whose previous credits included ITV's long-running sitcom The Larkins), it was hoped that this might be the vehicle for another extended run on the small screen, but it was not to be. Much-hyped by ITV (which was in a hurry to catch-up with the BBC's success rate with sitcoms), the promotional push seemed merely to provoke a negative reaction.

'I have seen this series described as a new Steptoe And Son,' wrote one rattled reviewer after watching the opening episode. 'It turned out to be not even new Jewel & Warriss.' Another complained that the two stars had been 'squeezed into a situation that cramps their style,' and predicted that the formulaic nature of the whole affair might make the more discriminating viewers 'wonder whether fresh, lively, hilarious television is dead'.

The show never recovered. ITV, panicking at all the critical press, pulled the series from its schedules after only four of its thirteen episodes had reached the screen. It was claimed that the series was being paused while certain revisions were made to its style, but it would never actually return.

The cancellation was a painful blow to Jewel & Warriss, who had already started to notice that power was shifting in the show business world of the early 1960s. A younger comic pairing, Morecambe & Wise, had not only recently lured away their favourite writers, Hills and Green (although it should be noted that Ben Warriss had been decent enough to recommend them to Eric and Ernie), but had also taken over from them on television as the leading double act of the day. Another youthful duo, Mike and Bernie Winters, were also starting to get plenty of exposure, as well as many of their old guest spots on the most popular variety shows. Now in their fifties, Jewel & Warriss were starting to feel old and out of fashion.

A dispiriting sign of how rapidly they were now slipping down the hierarchy came when, in the absence of any more TV projects, they were booked to entertain American troops stationed in Germany, and military officials there insisted that they audition before being allowed to perform their shows. 'We were treated as if we were two little insignificant people who could be sent home with our hands slapped,' Jewel complained.

They flatly refused to comply and flew straight back home to Britain. It had been, they said, a humiliation.

They proceeded to sue the agents responsible (one of whom, Don Arden, would later acquire far greater notoriety as the so-called 'Al Capone of Pop'), and in their 1964 High Court action they were awarded a large sum in damages along with costs, but much of the hurt remained. Once hailed as the biggest comedy stars in Britain, they had now been made to feel like yesterday's men.

They drifted on for a while, playing more modest summer seasons and pantomimes (a couple of which, ironically, had been offered originally to Morecambe & Wise, who were now far too busy on TV) as well as touring the provincial clubs. There were also some residencies on cruise ships, and they got involved in promoting an ill-fated project to build an entertainment complex (called 'Wonderama') in Morecambe. They made what would turn out to be their final television appearance as a proper double act, on 5th March 1965, in an episode of a BBC One variety show called Club Night.

Work, however, was not only proving harder to come by, but also harder to enjoy. 'Some places wanted blue stuff,' Warriss would later complain. 'It meant we had to change our style.' Neither performer felt comfortable in such a context; neither of them was enjoying it any more.

Jewel suggested that they offer Galton & Simpson a large amount of money to write a sitcom for them, but neither Warriss nor their current agent seemed interested. 'They knew we were reaching the end of the road,' Jewel would say, 'and I think they were prepared to go down gracefully.'

In 1966, therefore, Jewel & Warriss decided to go their separate ways. The former was still not quite so keen as the latter to let go - indeed, when Warriss, knowing what a worrier his partner was, tried and failed to address the matter definitively face-to-face, and then elected to clarify matters via a letter, Jewel took to his bed for a week - but it did not take long before a mutual agreement was reached. Their thirty-two-year partnership, it was accepted, was finally over.

Although both of them struggled for a while to adapt to a professional life apart - 'It was like losing my right arm,' Jewel would say - neither man, on his own, would struggle in a material sense. Jewel was by no means faultless in his financial dealings - he had unwisely declined an invitation from Lew Grade, back in 1955, to buy into ATV - but, most of the time, he researched each opportunity carefully and had made some shrewd investments, which would see him accumulate a large portfolio of properties (including an entire block of apartments in Knightsbridge) and made him a millionaire.

Warriss, in contrast, was a happy-go-lucky gambler whose bank account tended to rise or fall depending on how he happened to be faring in his regular poker games. He was usually well enough off, however, to indulge his natural inclination to be generous to others, and would be well-known for his many charitable ventures.

Jewel moved into acting, finding a new wave of fame co-starring with Hylda Baker (albeit under considerable duress) in the popular sitcom Nearest And Dearest (1968-73). He then won further critical acclaim first on stage in the 1974 Trevor Griffiths play Comedians, followed in 1975 playing one of the leading roles in the London production of Neil Simon's brilliant meditation on the nature of double acts, The Sunshine Boys, and in 1977 with the portrayal of Willy Loman in Death Of A Salesman, and then in a number of TV plays.

Warriss, after the split, ran a restaurant for a while, but soon felt the pull back to performing, and started appearing in revues and pantomimes again. He also acted as chairman of the stage production of the BBC show The Good Old Days, turned up on the occasional panel game, and, following in his cousin's footsteps, tried his hand at a number of serious acting roles (including Billy Rice in a 1990 production of John Osborne's The Entertainer), while also investing in several hotels.

Jimmy Jewel and Ben Warriss had always been very different characters (indeed, one person who knew them well remarked that they 'might have belonged to different species'). Jewel, an introvert, was something of a depressive; Warriss, an extrovert, was always positive and optimistic. Jewel was never a joiner, whereas Warriss was a clubbable sort who was an active member of the Water Rats charity.

In spite, however, of the speculation that circulated after the double act broke up regarding the nature of their supposedly 'estranged' relationship - every couple of years or so some or other tabloid would run a story suggesting the two men had either always, or grown to, hate each other - they actually remained very good friends. Although they did not have too much in common, outside of reminiscing about the old days and playing games of golf, they continued to like, and, indeed, love each other, and were always supportive of each one's solo career.

They met many times quietly and privately over the later years, did the odd brief charity 'turn', and agreed to be reunited on television, on 15th October 1974, for an edition of the ITV show business nostalgia show Looks Familiar. They talked about the old times, sang some specially-written lyrics about their shared career, and seemed delighted to be back, in that moment, smiling face to face.

Ben Warriss would die, on 14th January 1993, at the age of eighty-three. He had been taken ill the year before while still appearing in panto, and was moved to Brinsworth House - the show business retirement home for which he had personally raised a huge amount of money over the years. When he was brought back on stage to give one final interview, he ended it, after charming his audience for an hour or so with his memories of performing, by saying, 'I miss it so much,' and then putting his head down and fighting back the tears.

'To me,' his cousin wrote in an emotional tribute, 'Ben was more than just a partner - he was a true friend'. Hailing him as 'the best straight man in the business', he went on to add: 'For me it was a privilege to have worked with him and I shall miss him every day for the rest of my life'.

Jimmy Jewel would himself pass away almost three years later, on 3rd December 1995, at the age of eighty-five. 'He made performing look easy,' said one of the obituaries, 'and he did it to perfection.'

By this time, sadly, the double act of Jewel & Warriss had long been forgotten by many, with the powerful popularity of Morecambe & Wise having eclipsed the sun that once had shone so brightly over them. It would be wrong, however, to allow their names to fade entirely away.

They might have been more limited than Eric and Ernie, and certainly left behind less to value in the vaults, but, as Abbott and Costello might have put it, they were on first, and they led the way, and their own achievements, in their own way and day, are definitely well worth remembering.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more