Très Chic: The unique comic genius of Chic Murray

I could say that if you want to appreciate British comedy fully then you need to know about Chic Murray. I could say that, but I won't, because it sounds like I'm ordering a chore. There's no chore at all in finding out about Chic Murray. It is nothing but a pleasure, because Chic Murray is one of the true greats of British comedy.

That he isn't better known these days is nothing short of shameful. He deserves to be celebrated as one of the most important, innovative and subversive comedians that Britain has ever produced.

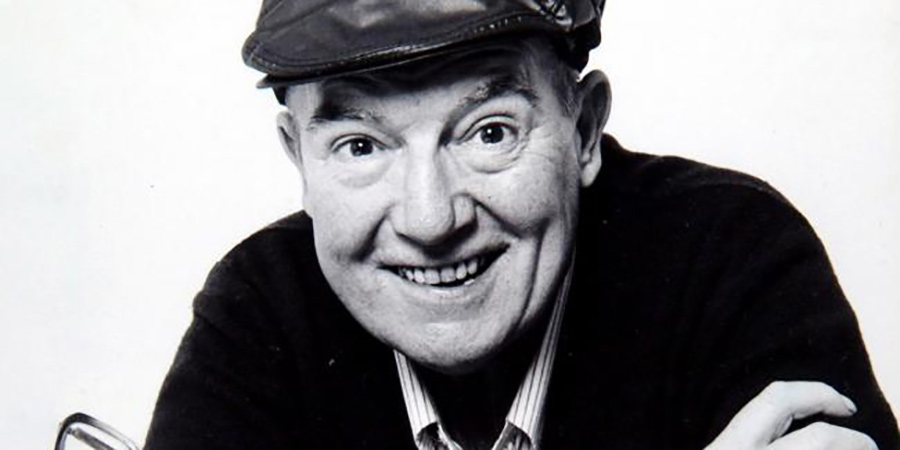

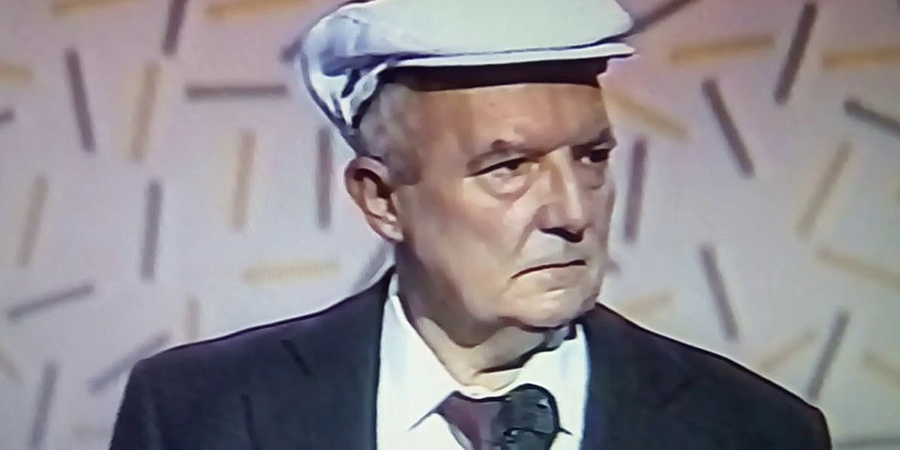

He was, it is true, an unlikely-looking subversive, but that was part of what made him so subversive. In his wipe-clean bunnet, his loosely-knotted Terylene tie, his 'comfortable' lounge suit and his finger-bendable shoes, he looked like he had just escaped from a Chums catalogue. He did not seem like a stand-up comedian. He seemed like a man who had been abandoned at a bus stop.

Behind that lost and lustreless look, however, lurked a bright comic soul in all of its dangerous, alluring, engaging, unpredictable and uncontrollable glory. Immanuel Kant once said of Murray's great compatriot, David Hume, that his stubbornly unrestricted thinking had woken him from his own 'dogmatic slumbers'. Chic Murray did much the same for anyone engrossed in comedy.

He changed the syntax of our thinking, making us pause and find strangeness in what was usually passed over as 'normal'. It was as if his own chronic efforts to become an ordinary person were constantly being thwarted by the sprite who was editing obsessively inside his head, forcing him to explain himself whenever he was trying to race through the banalities of everyday life.

It was like watching an extra-terrestrial trying to seem like a dull human being and believing, quite erroneously, that he was getting away with it. When Chic Murray talked about something routine that had happened, his expression suggested that he was not quite sure why it had happened, nor why people were now laughing at how he was saying it had happened:

This fellow approached me. And he stopped. So I stopped. Just to let him see I could do it. And he was surprised. He didn't say he was surprised. But I know he was surprised. I could see by his eyes. You know - he'd found someone as good as him...

Then each wonderfully rhythmic story would twinge and twist and turn and suddenly you were falling with him into a thick broth of Kafkaesque paranoia, Chekhovian quiet desperation and Celtic whimsy. Here, for example, is him in a hotel:

I'm staying in the local hotel here. And I'm not a complainer. But I made my way downstairs. I could see the manager looking at me. He said, 'What is it?' I said, 'I would like a door in my room'.

So after some time, a door arrived. Not on its own, of course. There were two fellows who brought it up. So once the door was fixed, I made my way out. Because I wanted to get out, y'know? So I turned this handle - there was another one on the other side, I noticed that on the way out. I never used that one - you'd need to have to put your arm around the door.

So the manager said, 'Have you got the door?' I said, 'Yes. The door's in the room'.

So then he said, 'You've no sooner got the door in and you start going out!' He said, 'It's funny, when you made your way in here, I thought, "Here's trouble!"' I said, 'Well, I don't think I've caused a great deal of trouble. It was just the door in my room'. 'Well, you've got one,' he said. I said, 'Yes, I have one'. 'And you're now going out for a little while?' I said, 'Yes'. 'Why?' I said, 'Because I don't want to stay in. That's why'.

So I made my way downstairs. The stairs led all the way down to the street, y'know? They led all the way up, too, of course. Saves them having two stairways there.

Here he is at the doctor's:

I went to the doctor. The nearest one I could see. And I made my way into the waiting room. I mean, you've got to know a doctor fairly well before you force your way into his surgery. So I sat down in the waiting room. There was a bench there, otherwise I wouldn't have attempted it.

And there were other patients there. At least I presumed they were patients. I didn't ask. I'm not a curious person. So I looked at her and I looked at him and wondered what was wrong with them. That's all you can do in a waiting room.

So after some time the door of the waiting room opened. And I looked. Just to give myself something to do. I've seen a door opening before - there was no novelty in it.

And someone came in. I wasn't surprised. But although there was ample room in the waiting room, he chose to sit beside me. I realised that as soon as he plonked himself down, y'know. He was in very close proximity. I thought I felt a nudge, I wasn't too sure.

And then he started speaking to me, this stranger, about this and that. Of which I know very little. He said, 'What do you think of this?' I said, 'Oh, I don't think much of that'. And I thought, 'If he comes out with a bag of toffees, I'm off!'

Here he is meeting a dog owner:

I said, 'You've got a nice dog with you'. He had a dog with him, otherwise I wouldn't have mentioned it.

He had it on a lead. He didn't seem to be too sure about it. He said, 'Yes, it is a nice dog'. It wasn't. It was a dreadful creature. It wasn't trained properly. You just had to stand there and hope for the best. I always think, if they can teach them to beg, they can surely teach them to look up and see if you're lit.

Anyway, he said, 'Do you know the Battersea Dogs Home?' I said, 'I never knew it'd been away'.

So he said, 'This dog - it may interest you'. He said, 'It can talk'. Then he looked down and said, 'Speak! SPEAK!!' He said, 'I don't know what's come over it. This would happen! I'll give it a touch of the hobnails - that always livens it up'. So he had a quick look around and then: THUMP! Then he looked down again and said, 'SPEAK!!!' The dog said, 'What will I say?' The man looked up at me and said, 'Aw, it doesn't make any difference. I'm getting it destroyed'. I said, 'Is it mad?' He said, 'Well, he's not pleased...'

Here he is at a wedding:

So I went to the wedding. A nice wedding. In Blackpool. Nice wedding. Just the usual type of wedding - a man and a woman getting married. That was all that was in it as far as I could see.

Eight times married - I didn't know that. But the fella sat beside me - he knew it. 'Eight times married,' he said, in a whisper that carried all over the church. And then I realised myself as soon as I heard the organist. He didn't play 'Here comes the bride'. He played 'Here we are again...'

There was a woman there with the longest nose I've ever seen. Now, I have nothing against long noses. We have them in our family. They run in our family. But she had a real beaut. You could have touched it. I didn't, but you could have touched it. And I thought, 'If things don't liven up, I'll touch her nose'. And what attracted me to it, speaking in the neutral gender, was the way she turned the pages of the hymn book with it.

And this woman with the long nose was seated opposite me. And I was trying to ignore her. Without being rude. Because it's so easy to be rude.

But I was fascinated by her nose. And what she could do with it. I watched her pick a bun up from the floor. I was just trying to turn it over with my foot at the time.

And then it all happened. Our eyes met, and I didn't know what to do, so I nodded. Y'know, I nodded as if to say 'Hullo'. And she nodded back - and she cut the cake.

Of course, the bride was in tears. So was the cake.

And suddenly, this woman with the long nose, she raises her head, and she's sniffing above. Sniff-sniff-sniff. And she said, 'There's someone cooking cabbage in Manchester'.

Anyway, I said to the bridegroom, 'Why has the cake got candles?' 'Oh,' he said, 'did you not know? It's the bride's birthday'. I don't know what age she was. The heat was desperate.

And this long-nosed woman was at my back. I knew that with the constant prodding I was getting. At least I was hoping it was her.

And then she slipped. And as she fell, she fell face downwards. And as straight as a die, she made directly for the tramline. And her nose lodged in the aperture of the line.

So we took a chance and a few of us bent down. And we tugged and pulled but we couldn't dislodge her nose. So we ended up picking her up by the legs and we wheeled her along to the depot.

This was the world of Chic Murray. It was a world in which social niceties were always problematic, pathways were puzzles, the insides of buildings were never to be taken for granted, stairways were extremely mysterious things, ordinary interactions were unnervingly odd, and strangers were very, very, strange. It was Scottish surrealism at its best.

Where did it come from? It seems simply to have emerged with Chic Murray from birth.

He was born Charles Thomas McKinnon Murray in Greenock, Inverclyde, on 6 November 1919, the son of a railway goods inspector. While most other children came to view the outside world as normal, he continued to regard it with a keen sense of suspicion.

After leaving school at fifteen, he served an apprenticeship in marine engineering at Kincaid's shipyard, then combined his labours there with spells on stage playing various instruments (including the piano, organ, banjo, mandolin and guitar), singing, yodelling and telling jokes in local amateur and semi-professional groups. We don't know much about these early years as a performer, other than the fact that, when his individual contributions were commented upon at all, they were praised for being 'droll'.

The major turning point in both his personal and professional life occurred in the early 1940s, when he met Maidie Dickson. She was an established performer on the Scottish variety circuit (having made her stage debut at the age of four), and quickly saw the potential that he had. They married in 1945, and she persuaded him to leave his engineering job and team up with her as a musical-comedy double act.

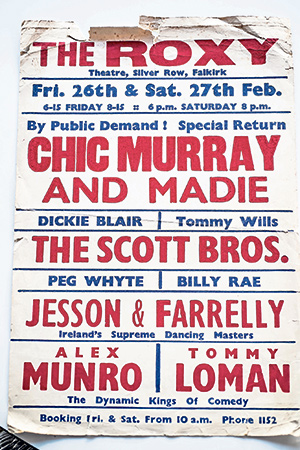

They made a striking visual contrast: he was 6ft 3in, and she was 4ft 11in. As they expected, it got them noticed. They were advertised, at various times over the next few years, as 'The Lank and the Lady'; 'The Musicienne and The Madskull'; and, most memorably, 'The Tall Droll with the Small Doll'.

Although they interacted on stage and sometimes switched positions, she focussed mainly on the musical side (being a very accomplished singer and accordion player), while he specialised in telling increasingly surreal-sounding stories about the mundane details of ordinary life. The combination worked, and audiences loved them.

Appearing in pantomime in Motherwell in 1948 as the ugly sisters, one reviewer wrote: 'If you have never laughed before, this pair will split your sides'. By the early fifties, while both were still being widely praised, he was starting to attract particular attention for his 'deadpan fun'.

Signed up by the powerful Bernard Delfont agency in 1955, the duo made the breakthrough beyond Scotland to UK-wide performing circuits, rising rapidly up the bills, appearing frequently on TV (they had their own monthly show called Highland Fling) and winning plenty of critical plaudits. Their future looked increasingly promising.

By the early 1960s, however, Maidie decided she wanted to retire, and Chic had no choice but to go solo. This should have seen him go on to match, or even eclipse, most of his comic contemporaries, because his style was so refreshingly distinctive, inventive and eccentric.

While most other British comics were reliant on standard one-liners and formulaic anecdotes, Chic Murray was intriguingly unpredictable. His take on summer season digs, for example, was so different from the usual gags: 'I was looking for lodgings. So I went up to this boarding house. The landlady said, "Do you have a good memory for faces?" I said, "Yes. Why?" She said, "There's no mirror in the bathroom"'; 'I rang the bell of this small bed-and breakfast place, whereupon a lady appeared at an outside window. "What do you want?" she asked. "I want to stay here," I replied. "Well, stay there then," she said and closed the window'.

He would also pick prosaic language apart like a baffled mechanic with his head stuck under a car bonnet: 'If something's neither here nor there,' he would complain, 'where the hell is it?'; 'I made a stupid mistake last week. Come to think of it, did you ever hear of someone making a clever mistake?'

It was the same when he recounted supposedly ordinary incidents from his life: 'I fell over in the street. It wasn't intentional. It held no appeal for me at all. But a woman saw it happen and came over to me as I was lying in the gutter. She said, "What's the matter - did you fall over?" I said, "No. I was trying to break a bar of chocolate in my back pocket"'; 'I met this cowboy with a brown paper hat, paper waistcoat and paper trousers. He was wanted for rustling'; 'My next-door neighbour said, "Is it okay if I use your lawnmower?" I replied, "Certainly, just don't take it out of my garden"'; 'I was in this restaurant, and the waiter came over and said, "Aperitif, sir?" I said, "Why, is the steak that tough?"'; 'I met this fellow at the Olympics. I said, "Excuse me, but are you a pole vaulter?" He replied, "No, I'm German, but how did you know my name was Walter?"'

It was the same when he talked about his family: 'My father was a simple man. My mother was a simple woman. You see the result standing in front of you: a simpleton'; 'I had a tragic childhood. My parents never understood me. They were Japanese.'; 'My father took me on holiday when I was a child. We went on a bus. We were going down a hill, and the driver lost complete control of the vehicle. It careered down the hill, completely out of control, and smashed into a wall at the bottom. I wasn't hurt, but luckily my father had the presence of mind to kick my head in'.

No one else was doing material like this at that time. He was just so beguilingly odd.

Other comedians loved him. Eric Sykes adored his 'naturally droll character'; Bruce Forsyth was in awe of his timing: 'immaculate and so different'; Jimmy Tarbuck said, 'Chic was the comedian all the other comedians wanted to watch'; Ronnie Corbett described him as 'a true original: a funny, sweet and engaging man who as a comic was ahead of his time'; Barry Cryer called him 'a surrealist who went his own way'; and Spike Milligan rated him 'the world's funniest comic'.

The problem was, however, that Chic Murray was, by this time, managing himself, and he was a very bad manager. He sat back when he needed to be pushed. He passed on offers that he should have pounced upon. He drifted when he should have been driven.

By the start of the 1970s, his health was failing and his marriage was on the rocks ('If it weren't for marriage,' he once reflected, 'husband and wives would have to fight with strangers'). He and Maidie, although they would always remain very close, divorced in 1972.

He flitted in and out of public consciousness after that. He had already branched out into acting in the mid-1960s (the director Joe McGrath, a fan and fellow Scot, had cast him in the ill-fated Peter Sellers Bond vehicle Casino Royale in 1967), and he would do more from this point on, winning particular praise for his cameo performance as the piano-playing headmaster in Bill Forsyth's 1981 movie Gregory's Girl ('Off you go, you small boys!'), and for his unlikely but brilliant portrayal of Liverpool FC's inspirational Glenbuck-born manager Bill Shankly in Bob Carlton's 1984 stage play You'll Never Walk Alone.

He also continued to pop up on television occasionally, sometimes as a panellist on such shows as Jokers Wild, and sometimes doing guest spots on everything from Celebrity Squares to an entertaining routine in an episode of the Eric Sykes sitcom where he played an overworked ticket vendor.

He should have been a fixture on British TV, particularly given the BBC's need to keep up its yearly quota of 'regional' programmes, but, in one of those seemingly inexplicably unfair twists of fate, while the far inferior Welsh comedian Max Boyce was given plenty of UK airtime by the Corporation to share his 'hilarious' tales about Welsh rugby, Chic Murray remained strangely underused by the national networks.

It certainly didn't help that he continued to hirple on, as his fellow Scots might have put it, without a proper London-based agent putting in the calls on his behalf. It didn't help, either, that he had scared the odd producer in the past with his mischievous flights of fancy (he once tricked the chat show host Simon Dee into trying to repeat the name of the French Polishers for whom Chic claimed he had once worked: 'Hunt, Lunt & Cunningham').

It probably did not help that he had developed an intermittently unhealthy relationship with alcohol. It also probably did not help that he seemed almost as mysteriously 'unusual' in his personal life as he seemed in his comedy routines.

Billy Connolly, for example, who was one of his biggest fans, once invited him over to his home for dinner. Murray surprised him initially by turning up with a large doctor's-style bag that suggested he was planning a sleepover, but then puzzled him further by heading to a guest room, reaching into the bag and pulling out a beige-coloured landline telephone. 'What do you need that for, Chic?' asked Connolly, understandably confused. Murray, blank-faced, merely looked him in the eye and said mysteriously, 'You never know...'

Something similar occurred when a friend paid a visit to Murray's own house in Edinburgh. Needing, at some stage, to go to the bathroom, the guest was bemused to find that there was a shower at either end of the bath. Once he came back out, he asked, 'Why have you got two showers in your bathroom?' Murray, again as dead-pan as he was on stage, simply said, 'You never know...'

Even his two children, Annabelle and Douglas, were well aware from an early age that their father was somewhat eccentric. 'When he got upset,' Annabelle would later recall, 'he'd run into the landing and shout, "Call for Mrs Pollock... Call for Mrs Pollock!" To this day nobody has a clue who Mrs Pollock was, or if she even existed'.

What is undeniable, however, when considering why he failed to fully hit the heights, is that he was the victim, time and again, of freakishly bad luck. Each moment when it looked as though he was about to race up to another level of stardom, something intervened to leave him stranded right where he was.

In October 1956, for example, when he was still performing as part of a double act with his wife, it was announced that they had been chosen to appear in the following month's Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium, alongside such stellar figures as Tommy Cooper, Liberace, Vivien Leigh, Terry-Thomas, Gracie Fields and Sir Laurence Olivier. It was set to give them unprecedented exposure and open up a whole new network of lucrative engagements for them. Then - just four hours before the curtain was due to go up - the whole thing was suddenly cancelled.

The producer Val Parnell interrupted rehearsals to inform the cast that he had received a message from the Palace announcing that the show would have to be abandoned due to the mounting Suez Canal crisis. While Liberace burst into tears and many other performers looked stunned and distressed, Parnell went on to explain that, at that very moment, British troops were landing in Port Said, Egypt, and the Soviet Union was threatening to retaliate with rockets unless British and French forces accepted a ceasefire, and so the Queen had decided that it would be inappropriate to attend the event.

Chic and Maidie, like the other stars, still received the commemorative documentation to confirm their presence at the show that never actually happened, and then it was back to the same old circuit. A huge chance had been snatched out of their hands.

Something similarly cruel happened some years later, when a Los Angeles-based agent saw him in one of his movie cameo roles and absolutely adored what he had done. He thus made contact, and promised that he was going to transform his career, get him work in America and more opportunities in movies. Murray was delighted. Then the agent returned to America and was killed in a car crash a fortnight later. Another career-changing chance was gone.

The result was that relatively high profile appearances from Chic Murray continued be rare pleasures during the final few years of his life. There was the odd chat show appearance, the occasional panel game and a solitary spot on a nostalgia programme, along with some of his ever-popular stage shows, but there should have much more.

He died on 29 January 1985, in Edinburgh, from a perforated duodenal ulcer. He was aged just sixty-five.

Even at his funeral people seemed to be hoping there might be more from him. His tartan bunnet was on his coffin as it moved along the conveyor belt, and at one stage it hit a hitch and the coffin shook slightly, causing the bunnet to flip up, as if signalling a last 'cheerio'. At that point everyone in the church stood up and applauded, and Billy Connolly put his hand up and shouted out: 'Please, please, not too much - the bugger'll come back and do twenty minutes!'

It was apt that Billy Connolly was the one who interjected, because he, more than anyone, had always idolised the comedian he called 'the funniest man on earth':

He was my hero. God I loved him. He was so funny, he used to make me cry with laughter. He wasn't just a great Scottish comedian, he was a great comedian full stop. They should have a statue to Chic Murray in Edinburgh. Never mind these Roman fuckers that nobody knows who they were! Put up a statue to the great Chic Murray.

There have actually been several campaigns in recent years to erect a statue in memory of Chic Murray. Most notably, in 2011, the businessman Colin Beattie, the owner of the Oran Mor bar and restaurant and a long-standing champion of the arts in Glasgow, commissioned a larger-than-life statue of Chic Murray alongside his protégé, Billy Connolly, from the distinguished sculptor David Annand.

Entitled The Patter, the 7ft £100,000 piece depicted the pair at opposite ends of a see-saw, with the senior Murray standing upright with the young pretender Connolly hunched over. As handsome a piece as it was, however, it was destined to languish in the darkness of a storage warehouse indefinitely because of an inaptly humourless land dispute with Glasgow City Council. A petition was launched, urging the council to hand the land over to the Oran Mor - but bosses cited 'pedestrian footfall' and 'damage to the trees' among their reasons for refusing the demand.

The ongoing fight for a joint memorial goes on, and has been reinvigorated this year in Scotland by The Sunday Post. 'If this statue is erected,' the newspaper quoted Murray's daughter, Annabelle, as saying, 'I think it will be quite overwhelming to see my dad and Billy together on the streets of the city they loved and which loved them back. I'd feel extremely proud and would love it for Billy too'.

The campaign deserves widespread support. You probably already appreciate the achievement of Sir Billy Connolly, but if you don't yet know enough about Chic Murray, then you are in for probably the most enjoyable research project of your life.

The man was very special, and it would be apt, as well as nice, to have somewhere to visit and tip your own bunnet to the great man's memory.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more