Fraternally Yours: The Brotherhood of British comedy

We all know the Groucho Marx line: 'I don't want to belong to any club that would have me as a member'. Historically, however, British comedians have so wanted to belong to a club that would have them for a member that they founded not one but two of them all for themselves.

It had something to do with insecurity; rather like Tony Hancock, after he discovered that his blood group was rhesus positive, many comic performers saw a reason to stick together ('A minority group like us, we could easily be persecuted!'). It also had something to do with an inclination to play a more positive role in public life; blocked, in stuffier and more snobbish times, from the conventional routes for doing so, they manufactured a means of their own.

For one reason or another, the door has thus been open, for more than a century, to those of Britain's comedians who have wanted to belong to their own semi-private community. This, then, is the story of how our comics became so clubbable.

It all started with a small trotting pony named Magpie. The year was 1889, and, following a well-received theatre appearance in Newcastle, Joe Elvin, a popular music hall comedian of the time with a fondness for eccentric public stunts (often involving sprint challenges to prove that 'England is not in danger'), had somehow been convinced to 'borrow' the animal from the theatre owner and racing enthusiast Dick Thornton and take her with him on the train all the way back to his home down in London.

Unsure of quite what to do with her there, Elvin was encouraged by a couple of his comedy friends - the 'scientific swimmer' James Finney and the trick cyclist Jack Lotto - to start entering her in the local Sunday morning harness races that were being held on a regular basis between the Horns Tavern in Kennington and the top of Streatham Hill. Much to his surprise and delight, Magpie (who was stabled near his home at 63 De Laune Street) proved such a competitive performer that, within a few weeks of her arrival on the local racing scene, Elvin was able to form a syndicate to cash-in on her regular wins.

Little more would have come from the enterprise, other than some extra bank notes, if it had not been for a colleague of Elvin's called Wal Pink. A popular writer as well as performer of comic songs, sketches and revues (including, in collaboration with Elvin, The Hansom Cabby), Pink was also a man of strong religious convictions, and soon felt so uneasy about benefitting from the money being made from betting on this pony that he began urging the syndicate to start donating their winnings to charity.

All of those involved were comfortable enough financially (and sufficiently ambitious about enhancing their social reputations) to agree to Pink's suggestion, and, gathering together for a discussion over a glass or two of beer, resolved to form a society that could distribute the funds to various good causes of their choice. A number of names were considered, including 'The Noble Order of the Star', only for each of them to be rejected on the grounds that, for a bunch of working-class music hall comedians, they sounded 'a bit bleedin' high falootin'.

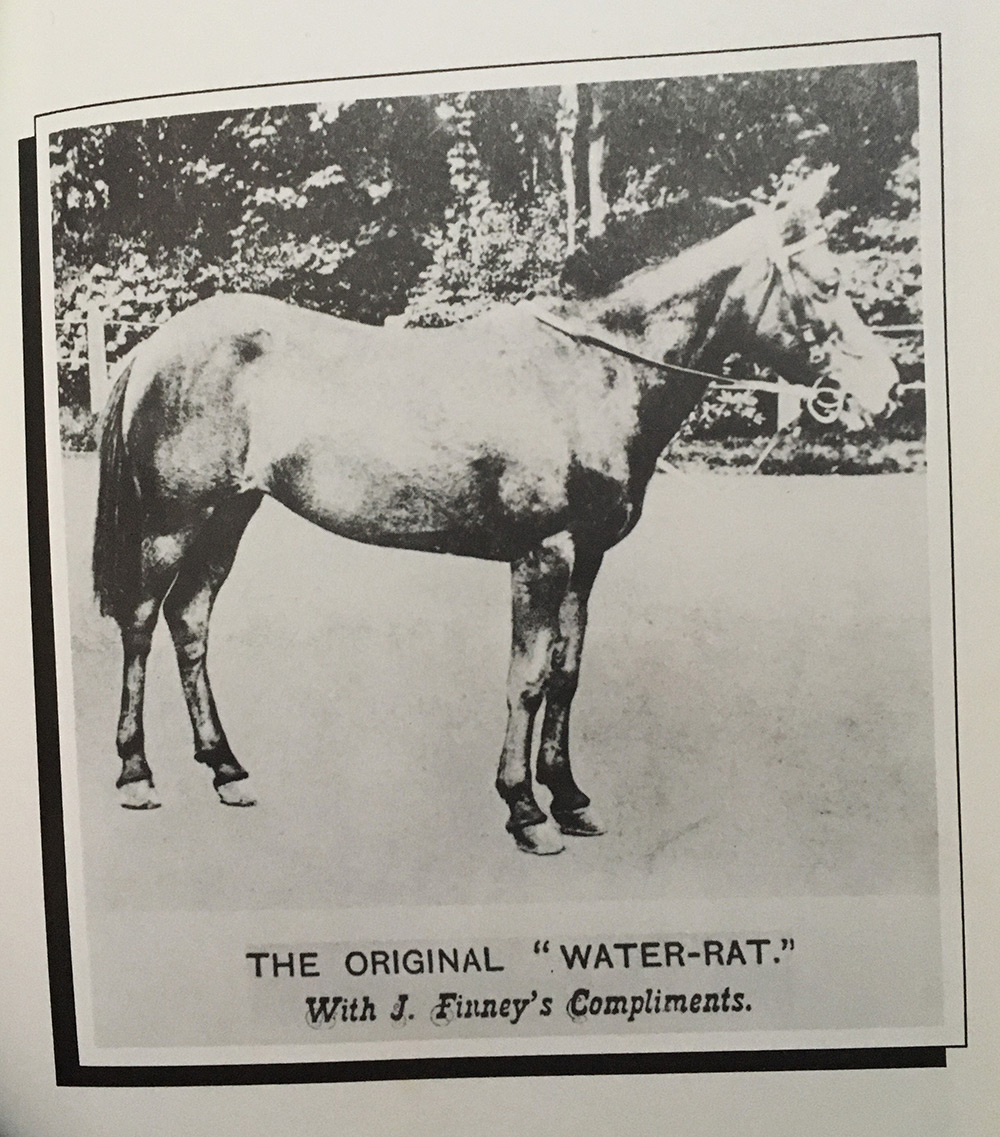

Inspiration finally arrived one wet and windy day, when a passing bus driver, upon seeing the drenched little pony pulling its cart, leaned out of his window and shouted that it looked 'more like a bloody water rat!' It struck a chord with a group of performers who, though now successful, still thought of themselves and others in their profession as under-appreciated underdogs (they also liked the fact, once someone brought it to their attention, that 'rats' spelt backwards was 'star'), and so they adopted it not only as Magpie's racing soubriquet but also as the name for their new community.

'The Pals of the Water Rat', as it was known initially, thus started to take shape. The first twelve members were Joe Elvin, Wal Pink, Jack Lotto, acrobats Fred and Joe Griffiths, comic singer and impersonator George Fairburn, one-man band Tom Brantford, comedian Arthur Forrest, comic singer and pantomime dame Harry Freeman, theatre manager Barney Armstrong, entrepreneur Fred Harvey and the landlord of their local pub (the White Horse in Brixton) George Harris.

They started meeting regularly from the summer of 1889, usually at the White Horse, where it was reported that the atmosphere during one such occasion 'was charged with the delicious odour of tripe and onions', and the evening's entertainment was enhanced by 'songs, smoke and champagne'. It was during these boisterous affairs that the aims and government of the group were debated, agreed upon and then recorded by the so-called 'scribe' of the society, Wal Pink.

The first official meeting of what by this time was being called 'The Select Order of Water Rats' (and would later be renamed again - this time definitively - as 'The Grand Order of Water Rats') took place on 11 April 1890. 'Philanthropy, Conviviality and Social Intercourse' was enshrined as its motto, with funds from the new charity being dedicated to helping fellow artistes who were injured, sick or had fallen on hard times.

As for the ranks and rituals of the organisation, the founders drew, ironically enough, on the bits and pieces of gossip they had gleaned about the various (men only) fraternities and masonic lodges which had so far shut them out. It was decided, for example, that their own community would have a similar air of exclusivity about it, as well as a degree of inscrutability, to mimic something of the snooty respectability of the older and grander institutions.

Their leader - dubbed the King Rat - was to be selected from the most eminent and admired figures in the music hall world, and would serve for a year before handing it on, following another election, to someone of similar stature. Dan Leno, probably the most popular music hall performer of the era, was the first to be offered the position, but, due to the pressure of other commitments, he passed (but would accept it for a later year), and Harry Freeman agreed to take up the role in his place.

The level directly beneath the King Rat was to consist of a sort of rodent cabinet, made up of the most active and experienced of the senior members, called the Grand Council. The rest of the membership was divided in terms of length of involvement, signified by the wearing of blue collars by the most senior, red collars by the middle tier (those who had at least ten years' participation), and white (signalling purity) by the most junior members.

Those who wished to join the Water Rats would have to be recognised as being part of the entertainment profession, and be proposed and seconded by existing members. Their application was then to be discussed in General Council, and then by the broader membership of the Lodge, and then the ballot paper was distributed to all, with a minimum of seventy-five per cent affirmative votes required of the total membership. The candidate was then summoned, blindfolded, to the Lodge to be questioned, and then the blindfold was removed and the new Baby Rat admitted.

The workings of the society would soon grow even more self-consciously elaborate and strangely abstruse. Among the other functionaries identified as time went on would be the Prince Rat, Bait Rat, Collecting Rat, Test Rat, Scribe Rat, Musical Rat and the Preceptor, along with the Trap Guards and honorary Companion Rats. As if this was not 'bleedin' high falootin' enough, a later invented tradition would see a member judged to have elicited a good enough belly laugh among those present to be rewarded by being presented with the Jester's Medal (a star-shaped metal decoration on a blue ribbon), while - following a playful suggestion from the visiting Rats Laurel & Hardy - anyone unfortunate enough to gain only groans from an attempted gag would be obliged to wear the Golden Egg (a large, heavy and quite cumbersome oval-shaped piece of wood) for the remainder of the evening.

It was also decreed that every member of the order must wear a small gold badge, shaped as a water rat, on the left lapel of their jacket, and if one Water Rat met another who was spied not wearing said badge he was to be fined, with the money (which is never referred to as 'money', only as 'coins') being donated to charity. The comedian Charlie Chester, in his exasperatingly evasive history of the order, acknowledged that there were many other rules, but added that 'I feel it would be wrong to tell them all'.

In spite, however, of such internal affectations, the Water Rats would go on to live up to their founding ideals as a force for good in their profession. Basing themselves from 1901 in The Vaudeville Club at 98 Charing Cross Road (they can now be found within the cosy confines of 328 Gray's Inn Road in Kings Cross), they worked impressively hard to raise funds to assist those of their fellow performers who were struggling financially, provided guidance and support for those whose rights were being undermined or ignored, and generally did what they could to promote the notion that popular entertainers were just as worthy of respect and appreciation as those in the so-called 'legitimate' theatre (or, indeed, those labouring on the factory floor).

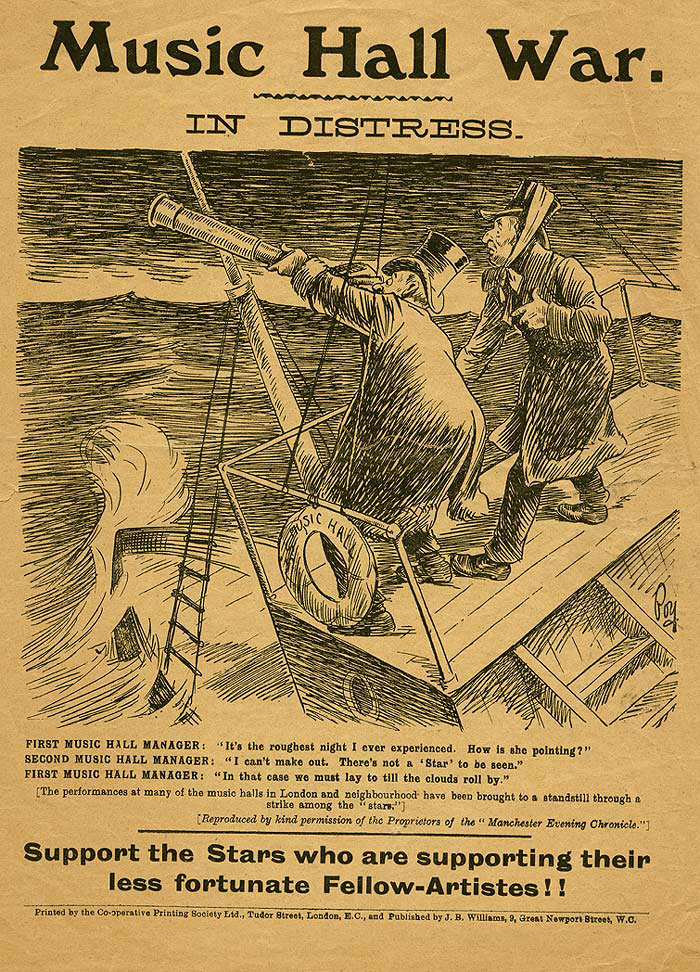

In 1906, for example, the Water Rats were a driving force behind the formation (and funding) of The Variety Artistes' Federation, a trade union that would campaign for better working conditions for music hall performers and lead the fight against the then all-powerful theatre managers. It quickly acquired a membership of nearly four thousand entertainers, finally giving them a clear and coherent voice in political debates and battles.

Among the other early achievements of the Water Rats was the idea, first put forward by Joe Elvin and his colleague Joe O'Gorman, to establish the Variety Artistes' Benevolent Fund to care for those in the industry who were sick, impoverished or elderly. A related initiative - again originating with Elvin - was to find sufficient investment to purchase a special retirement home (later nicknamed 'The Old Pro's Paradise') for veteran performers - Brinsworth House, a mansion on the outskirts of Twickenham, the ownership of which was secured in 1911 - as well as lobby to acquire the cachet of royal patronage, which, following a trial run in 1912, was achieved in 1919 in the form of first of the annual Royal Command Performances (along, for a while, with a nationwide philanthropic exercise called Brinsworth Week), to continue raising funds for this and related causes.

Distracted by the pains and strains of the First World War and the subsequent economic depression, the Water Rats waned for a while (and they actually disbanded completely from April 1922 until April 1928), but gradually regained their old purpose and prominence within the profession once circumstances allowed. Its membership expanded, and in 1929 a 'sister' community, The Grand Order of Lady Ratlings, was established to accommodate the growing number of female performers who also wished to be involved (members would later include Sophie Tucker, Ivy Benson, Vera Lynn, Pat Phoenix, Carmen Silvera and Barbara Windsor).

The Water Rats went on, first, to do what they could to fight against the decline of the Variety circuit, funding their own tours and offering financial support to keep struggling theatres open, and, then, they liaised with the broadcasting companies to help as many performers as possible make the transition to television while supporting those who fell by the wayside.

It was by now a venerable show business institution in its own right, boasting not only many 'local' stars as members (the list included Sid Field, Robb Wilton, Will Hay, Ted Ray, Tommy Trinder, Arthur Haynes, Freddie Frinton and Flanagan & Allen) but also such international luminaries as Charlie Chaplin, Laurel & Hardy, Peter Lorre, Danny Kaye and Bob Hope, as well as such eminent honorary 'Companions' as Prince Philip and Prince Charles.

It was not, however, the only club in the comedy community. There was also a Masonic lodge.

Chelsea Lodge No 3098 was founded in 1905 expressly for entertainers. Like the other already-established fellows of Freemasonry, the principal attraction for those professionals in the entertainment world was the promise of a private place where one could socialise, network and combine to do good works.

A catalyst was the fast-growing tension at the time between artists and management. That particular industrial issue (which saw bosses not only try to control the movements of their performers, but also force them into appearing in more matinées per week for no extra money) would lead eventually to the Music Hall Strike of 1907 (resulting in a rise in pay), but there was also a broader culture of class-conscious conflict (as evidenced, for example, by the formation of the Labour Party in 1900) that was encouraging workers in all professions to crave greater solidarity and political nous and clout.

While the Water Rats might well have struck many performers of the time as providing them with precisely this kind of practical service, it seems that others were drawn to a more traditional, and apparently slyer and stealthier, template for protecting and promoting their currently somewhat precarious professional standing. Freemasonry, having thrived in Victorian business and society via a comparatively discreet but increasingly elaborate web of relevant connections, appeared to offer a tried and tested means of pursuing one's aspirational plans, and many entertainers now sought an entrance to its enclaves.

Some of them, perhaps, were also intrigued by the air of secrecy that surrounded these fraternities, as well as being curious about their campness and theatricality. While Britain's other branches of its working class would surely have found such a strange propensity for peculiar costumes and puzzling conventions unnervingly risible, or worse, many in the music hall brigade (already profoundly tired of, and alienated by, the common sight of the signs displayed in the windows of so many small rented properties, up and down the country, that warned: 'No Irish, No Jews, No Theatricals') seemed to consider such eccentricities as simply a sign of some much-needed kindred spirits.

One reason why any account of their admission and subsequent evolution must sound far more speculative than certain is the fact that - as so often seems to be the case with such societies - the archival evidence is largely unavailable. In the specific case of the music hall Masons, it has been claimed by their own official historian that the first fifty years of paperwork pertaining to their proceedings 'have been destroyed' (something spookily similar, it is said, happened to the records of the Water Rats), and so we have no real choice but to try to fill-in the gaps between whatever fragments we find.

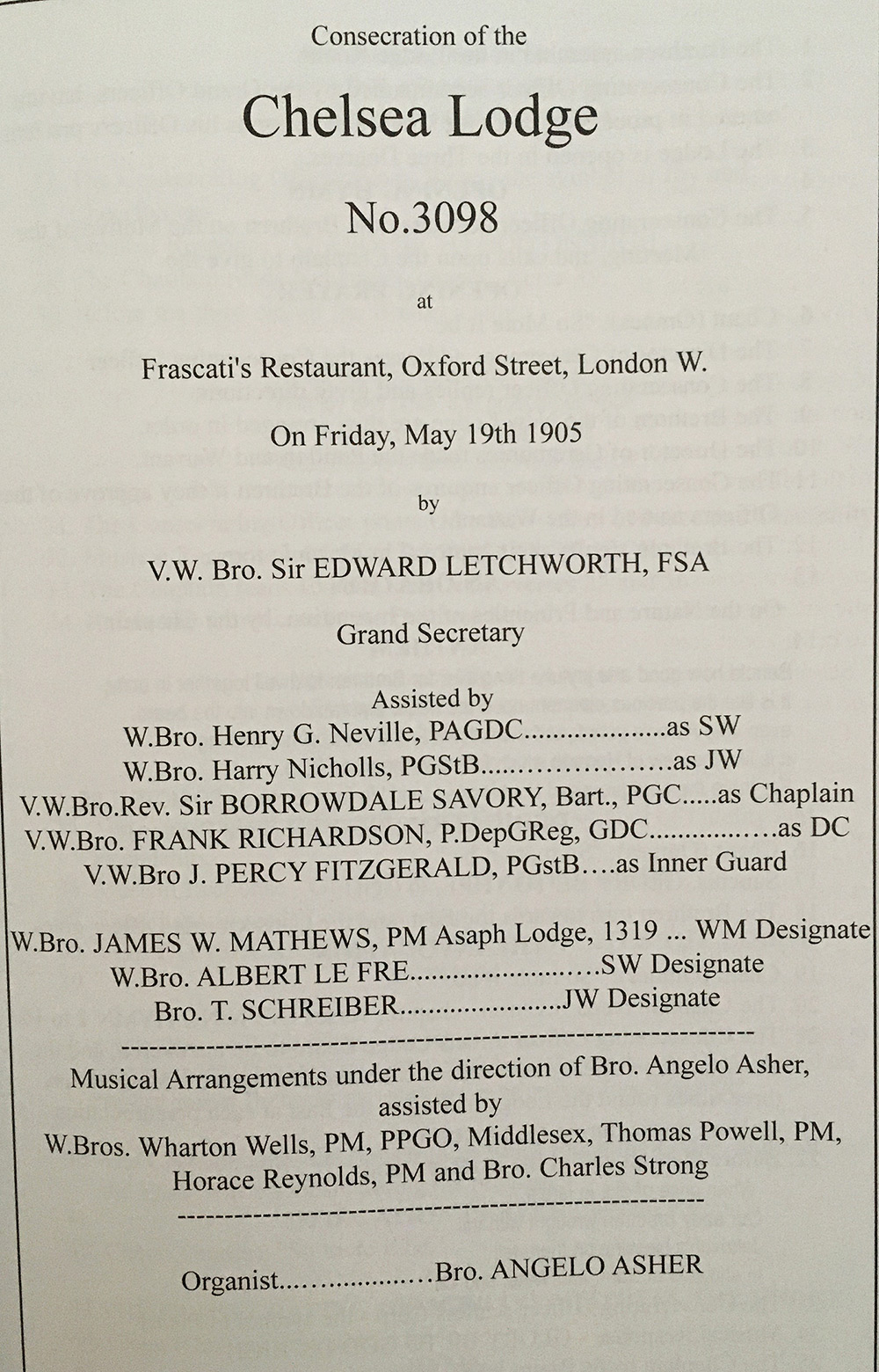

What we do know, from contemporary reports, is that a group of entertainers and backstage labourers, led by Wolfe Lyon (a theatrical upholsterer), got together one afternoon on 10 May 1904 at the Chelsea Palace Boardrooms, on London's King's Road, to plan a request for admission into the United Fraternity of Ancient and Accepted Masons of England. Once permission was given early on in the following year, the new Chelsea Lodge was formally established at a special consecration event held at Frascati's Restaurant in Oxford Street on 19 May 1905.

James Mathews, a New Zealand-born theatrical manager unusually sympathetic to the claims and concerns of performers, was elected to the position of Grand Master, with the stand-up comic George Robey, the character actor George Mozart and the playwright and pantomime artist Will Evans joining a wide variety of other comedians, singers, musicians, magicians and circus performers as founding members.

The location of the Lodge would change several times over the next few decades, starting at Chelsea Palace for a couple of years and then moving on to Chelsea Town Hall; the Queen's Hotel in Leicester Square; and the Royal Adelaide Gallery Restaurant in King William Street; before settling at its current address of Freemason's Hall, at 60 Great Queen Street, in 1936.

As happened with the Water Rats (many of whom would also, contemporaneously, be members of Chelsea Lodge), these meetings of the Masons would be characterised by all kinds of elaborate and arcane rules, regulations and rituals. There were similar bureaucratic hoops through which all applicants had to jump ('...no person shall be initiated, or Brother join, without having been proposed and seconded at one regular Lodge, and balloted for at the next regular Lodge, which ballot shall not take place unless his name, age, profession, and place of abode, with the names of his proposer and seconder, shall have been put in the summons to all the Members of the Lodge...'), similar sartorial accoutrements (including white gloves and light blue collars and aprons, which made them look as if they were ready to wash the dishes in the kitchens at Coventry City Football Club) and similarly intricate and idiosyncratic roles and offices (such as Almoner, Senior Deacon, Junior Deacon, Inner Guard and Tyler).

All members (once they had bared their left breast - to prove that they're not a woman - and rolled up their left trouser leg - to show that they're able-bodied) had three stages of Freemasonry to go through. The first is 'Entered Apprentice', which stresses the idea of equality and the duty to help others; the second is 'Fellowcraft Freemason', whose focus is on self-development; and the third and final stage, which emphasises wisdom and good reputation, led eventually to the highly-prized title of Master Mason.

No doubt many of those entertainers who joined Chelsea Lodge would have insisted that they, like the Water Rats, were motivated simply by the promise of friendship and togetherness, the pure appeal of the organisation's three core principles ('look after those less fortunate, improve yourself, and live life well so as to be remembered for the right reasons'), as well as perhaps a sense of social prestige (providing the public school experience some of them had imagined but never had) and the old pantomimic delight in dressing up and looking rather silly. It was undeniable, however, that participation could also, potentially, serve more basic and career-oriented purposes, with all kinds of influential industrial links suddenly ready to be winked into existence.

The dining and socialising that followed every lodge meeting, for example, certainly offered exceptional and unprecedented opportunities for networking between individuals, groups and companies involved in some or other branch of show business. Members could exchange information, seek credit, organise contracts, find employment, save employment, request or exercise influence, and ensure all kinds of benevolent support against the many cruel vicissitudes of a notoriously unstable profession.

It was this need for greater security, solidarity and discreet assistance, as well as a readiness, when able, to give something back to the wider society, that would see so many entertainers flock to the Freemasons over the next few decades. Peter Sellers, Dick Emery, Alfred Marks, Freddie Davies, Bernard Bresslaw, Arthur English, Jess Conrad, Joe Loss, Billy Dainty, Davy Kaye and Bob Monkhouse would all be among those in the post-war period of the last century who looked to the Masons to lend them just a little more of a lift than, as young up-and-coming performers, they might otherwise have found (many budding comedians, for example, started out in those days in revues at the Windmill Theatre, and the Windmill had at least eight Freemasons from the Chelsea Lodge currently on its staff, and so, once the word about that and similar connections began to spread, the applications promptly increased).

The fashion for such fellowship, however, soon faded, and, as a new spirit of individualism, irreverence and iconoclasm swept through the Sixties, a new generation of entertainers, from comics to rock stars, started reflecting on what little was known, rightly or wrongly, about such strangely coy and old-fashioned-sounding clubs, from the secret handshakes and weird-sounding initiation rituals to the rumours about secret industry deals and devious social machinations, and were far more inclined to mock them rather than join them.

Sketches about Masons, usually featuring a bland middle-class businessman wearing an apron with one or both of his pin-striped trouser legs rolled up to his knees, started creeping into the country's comedy content as more and more people became aware of how little they knew (or liked) about such shadowy associations. Monty Python's 'How to Recognise a Mason' sketch (from Series 2, Episode 4) was memorably eager in its mockery ('It opens doors, I'm telling you!'), with various bowler-hatted businessmen shown hopping down the street with their trousers around their ankles, stopping only to shake hands in the most physically-challenging of ways.

Plenty of sitcoms followed suit. Are You Being Served?, for example (from Series 7, Episode 7), featured the following exchange: MR HUMPHREYS: 'I can't stand secrets, can I, Mr Lucas?' MR LUCAS: 'No, you can't, Mr Humphries. That's why you didn't become a Freemason, isn't it?' MR HUMPHREYS: 'Er, one of the reasons'. (John Inman, incidentally, would go on to be anointed King of the Water Rats.)

'Allo 'Allo! (in Series 5, Episode 9) did much the same: FAIRFAX: 'I say, Carstairs, two men with ducks on their heads have just walked into the public convenience. What do you make of that?' CARSTAIRS: 'They're probably Freemasons'. (Gordon 'Rene' Kaye, by the way, would go on to be another King of the Water Rats.)

Toast Of London (Series 2, Episode 4) was among those comedy shows that devoted most of one storyline to the idea of such a society:

TOAST: My name's Toast, I want to be a Mason - today!

GUARD: You can't become a Mason just like that!

TOAST: Ed Howzer-Black said I could join.

GUARD: Oh, well, right - have you got the money?

TOAST: Yes - twenty-seven pounds and fifty pence.

GUARD: Yeah, well, I'm a little bit too busy today to do the paperwork, so you'll have to use the app.

TOAST: An app?? What, there's an app you can use to join the Masons?

GUARD: Yeah.

TOAST: Wow! ...What's an app?

GUARD: You ask Ed. He'll tell you. You download the app and I'll text you the password.

TOAST: Whoa, whoa, whoa - when do I get initiated?

GUARD: I'll let you know all about that. River ceremony. Bit of a booze up. Finger food. And you, sir, you get a goody bag.

TOAST: Oooh, great! ...Um, I say - what's a goody bag?

Most recently, in 2022, there was Mike Myers' The Pentaverate - a mini-series about 'a benevolent, fully-sequestered, secret society,' led by a blond scruffy-haired Englishman, a soulless Australian-American, an ex-Putin oligarch, a procrastinating nuclear scientist and Alice Cooper's former manager, which has been quietly governing the globe since 1347: 'You may also be asking, "When do I start running the world?"' a rare new member is told. 'Well, let's try walking the world first'.

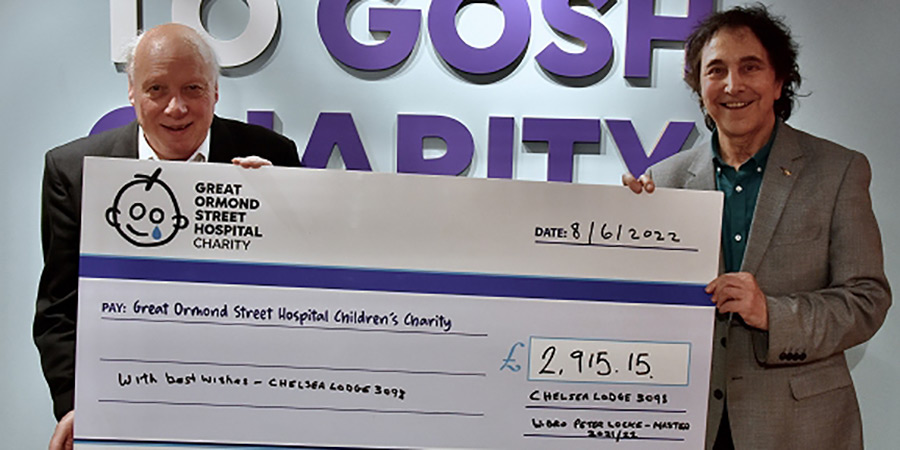

It is only fair to note, however, that, for all of the suspicion and satire that tends to come their way these days, the show business versions of these societies have also been seen to live up impressively to their charitable aspirations, raising and distributing millions of pounds over the decades for a myriad of worthy causes both inside and outside of their own professional provinces. 'What we could not have achieved separately,' the late Roy Hudd (a prominent participant) once said, 'we now achieve together'.

Today, the two bodies (while struggling somewhat to recruit from among the younger generations) continue to thrive, and, while some celebrities prefer to pick and choose which one to embrace (Mungo Jerry's Ray Dorset, for example, is a Mason, whereas Queen's Brian May is a Rat; Bradley Walsh is a Mason, while Jimmy Tarbuck is a Rat), there is still a considerable number of entertainers who find the time and inclination to be active members of both of these fraternities.

Jess Conrad, for example, is a Rat as well as a Mason, as is Jim Davidson, Ian Lavender, Roger De Courcey and Joe Pasquale, while the famously becaped musician and raffish wit Rick Wakeman remains a notably lofty presence in both camps, having been not only a King Rat but also a Worshipful Master of the Chelsea Lodge.

They do seem, these days at least, to be harmless and well-meaning organisations: having seen their old political concerns and campaigns largely taken over by more modern and muscular bodies, these gentler and contentedly nostalgic fraternities have settled into serving mainly as places where performers can relax and reminisce with old friends and sparring partners, have a pleasant meal and a few drinks, while feeling as though they are still capable of doing nice things for those who need them. Whatever more questionable endeavours may persist (or be developing) in other branches of the Brotherhood, these distinctive enclaves for entertainers seem as kind-hearted as they are quaint.

How long a future they have left is another matter. These days, the most successful comedians, with their high-powered personal management teams, are a far more relaxed and confident breed, and seem in far less practical (or, indeed, emotional) need of a community of like-minded comrades. With the likes of Comic Relief now channelling many of their charitable aspirations, and more informal, and far less 'dressy', private members' clubs (including, of course, the Groucho itself) having taken over the dual role of play pens and ports in the show business storm, it looks unlikely that Freemasonry and its neighbouring relations will prove any stronger a magnet for young comics than it will for the rest of our professions.

As for its far-ranging and rich history, however, it will surely continue to intrigue those whom it draws to explore. As places of rebellion and refuge, of scheming and succour, of eccentricity and escapism, they can shed a little more light, because of rather than in spite of their shadowy secrecy, into the lives and dreams and desires of those who, for so long, were treated like outsiders by some of the very people they worked so hard to make laugh.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more