The Big Spin: Billy Connolly and the art of adaptation

In comedy, imitation is rightly frowned upon, but adaptation is a seriously under-appreciated art. Imitation is usually equated with laziness, inauthenticity and, indeed, thievery; all one is doing is exploiting someone else's creativity. Adaptation, on the other hand, is quite another matter; it is not only creative in itself, but also a mark of the impact of character upon content.

There is certainly nothing appealing about joke-stealing. The joke thieves are the kind of people whom the philosopher Francis Bacon once likened to ants, because 'they only collect and use'. What they do is unoriginal and dishonest, because they simply repeat what someone else has written or said.

The adaptors, on the other hand, are the sort of people Bacon likened to bees, because the bee 'gathers its material from the flowers of the garden and of the field, but transforms and digests it by a power of its own'. What they do, in the comic world, is take an existing idea, or even a whole routine, and invest so much of their own wit, vision and personality into it that it becomes something that, while still bearing a family resemblance, is now significantly different from the original source material.

This is what tends to be obscured by the understandable anger about the joke thieves. The focus on their blatant borrowings (or, as some stand-ups call it, 'hooverings') has the unfortunate consequence of suggesting that all comedians are either entirely original or unoriginal, purely authors or imitators. The reality, however, is that very little, if anything, which emerges into the comic world is genuinely sui generis, and what passes as new and original is actually, to varying degrees, a fresh take on an existing idea.

What we need to do, therefore, is to stop being quite so obsessed with those who adapt material really badly and brazenly, and start being more appreciative of those who do it really well.

This has long been a common attitude in other branches of the arts. In opera, for example, Mozart, according to recent research, borrowed fairly heavily from The Beneficent Dervish - composed by several players from his inner circle - when he wrote The Magic Flute, while Puccini's Turandot owed its story to the romantic epic Haft Peykar ('Seven Beauties') by the 12th-Century Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi; and, in drama, George Bernard Shaw drew on Tobias Smollett's 1751 novel The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle when writing Pygmalion in 1913, which was in turn quite brilliantly re-imagined by Garson Kanin for his 1946 play Born Yesterday, and Shakespeare, of course, borrowed freely from the likes of Chaucer, Sir Philip Sidney and Plautus.

The same process of adaptation has long been evident in popular culture. John Lennon, for example, famously used a 19th-Century poster for Pablo Fanque's Circus, purchased from an antiques shop in Sevenoaks, to create the 1967 song Being For the Benefit of Mr Kite! ('Everything from the song is from that poster,' he later admitted, 'except the horse wasn't called Henry'). He also, two years later, reversed the arpeggios of Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata to serve as the basis for the comparably compelling Because.

Similarly, though not quite as exhaustively, George Lucas drew heavily on Akira Kurosawa's 1958 film The Hidden Fortress when making Star Wars in 1977, while Christopher Guest followed the formula of Albert Brooks's 1979 movie Real Life when starting his own series of so-called 'mockumentaries'. In yet another medium in 2008, the American street artist Shepard Fairey used Mannie Garcia's photograph of Barack Obama for his stencilled 'Hope' version, which became an iconic contribution of that year's US election campaign.

Whether or not one agrees with Oscar Wilde's contentious qualification - 'Talent borrows, genus steals' - the influences inherent in our inventions have grown increasingly apparent in recent decades. Television has been eating and regurgitating itself for ages, music is sampling its past to the point of self-parody, and in Hollywood it's now Groundhog Day even for Groundhog Day.

This brings us back to comedy. Thanks to the unprecedented amount of old comic material in easy access via the Internet - the audio, the video, the transcripts and the quotes - it's never been harder not to be influenced subliminally, let alone consciously, by existing ideas, themes and routines. The very evanescence of the experience - a quick glance at a tweet, for example, followed by another unrelated distraction - means that, although it is simpler than ever to search for the original authorship of something, there is less inclination to bother.

That is why, for example, the shamelessly lazy shoehorning-in of a very old joke about Diana Dors (the mayor of her home town, being so anxious not to mispronounce her real surname of Fluck, ends up introducing her as 'Diana Clunt') in 2019 on the first episode of This Time With Alan Partridge ('And here's Alice Clunt'. 'It's Alice Fluck, actually'. 'Ah yes, I see what I've done'), was greeted by many on social media, and in newspapers, as if an ingenious new gag had just been heard.

The provenance, though never irrelevant, arguably matters rather less, however, when the appropriation leads to the genuine craft of adaptation. Some performers do not just lift material; they liberate it from a lesser form.

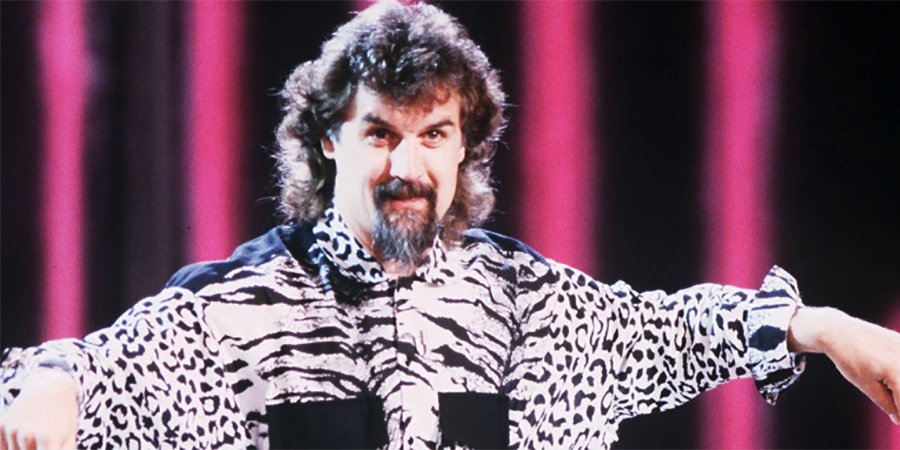

A case in point is Sir Billy Connolly. It was while I was 'ghost-editing' (or, as I believe the more fashionable phrase now puts it, 'ghost-curating') his recent collection of comic material, Tall Tales And Wee Stories, that I became aware of just how well-evolved his skills of adaptation had become over the course of his long career. It is, indeed, hard to think of anyone better at planting a personal flag in someone else's material ('Connollising'?) and gradually cultivating it into something fresh and fertile.

In the early days of his career, there was indeed a fairly 'normal' amount of basic 'hoovering' going on, as he looked for ideas from practically anywhere and everywhere. In his first TV special in 1976, for example, there was a veritable procession of very old club gags parroted for public approval (e.g. straight repeats: 'There was this Irish guy who bought two hundred acres of land - the tide was oot'; and slight revisions: 'What about the two Laplanders doing the crossword? One says to the other, "Oh, Michael, I've got a hard one here". He says, "What's that?" He says, "It's got four letters, and old MacDonald had one". He says. "I've got it - it's a farm!" The other one says, "Ah, yes, of course". He says, "How do you spell that?" The other one says, "I think it's e-i-e-i-o"').

By his own admission, he also took a joke from a musician friend of his called Tam Quinn ('Jesus's apostles were eating a Chinese takeaway when Jesus came in. Jesus asked them, "Where did you get that?" and they said, "Oh, Judas bought it. He seems to have come into some money"'), told it that night during his set, and immediately got a positive reception. In the next few months, as a consequence, he would build on it until it became his early classic, the 'Crucifixion' routine.

Even his celebrated breakthrough gag on Parkinson, in 1975, about the half-buried bum that served as a parking space for a bike, had been in circulation for ages up and down the northern pubs and clubs. His distinctiveness in using it there was simply in being the first one to believe, unlike so many other comics of the time, that he could get away with telling it on a mainstream TV show.

Even later on in his career, there would still be the odd act of somewhat crude appropriation, such as the line that was 'borrowed' from the 1976 TV special, The Barry Humphries Show, which featured Edna Everage in Stratford-upon-Avon (spying a passing Morris Traveller, the housewife but not quite yet a superstar exclaimed, 'Oh, look, there's a little half-timbered car. I love those, I call them Tudor cars!'); this turned up again in a fine 1991 Billy Connolly routine about Scottish women and scones ('They've all got Morris Minor Travellers, with the wood - it's a sort of Tudor estate car!'). He also clearly leaned quite heavily on Richard Pryor's material from the late 1970s when developing his 'Shouting at Wildebeest' routine a couple of decades later; he was indebted to George Carlin's material in the 1996 show Back In Town, from which he picked and mixed to develop his own variations on the dangers of 'beigism'; and dipped into Dave Allen's later riffs on language, commercialism and the nature of ageing to engage with the same range of themes.

Most of the time, however, as a mature comic performer, he could reformulate a specific joke or story, reanimate it from within, and the 'Connollisation' would be complete. Take, for example, the very basic joke that, of all people, Bernard Manning had been telling since (at least) the late 1960s:

A Jewish fella is on his death bed, and he says to his wife, 'Are you there, Becky?' She says, 'I'm here, Hymie'. He says, 'When I came home from the war in 1918 wounded, Becky, you were by my side. I entered the concentration camp in 1933,' he says, 'Becky, you were by my side. I opened that little shop just after the war and I went bankrupt, didn't have two shillings to call my own,' he says, 'and you were by my side. I'm dying now, and you're still by my side. Becky,' he says, 'you're a jinx!'

In the early 1980s, Sir Billy 'revived' it, but also adapted it, to turn it into this routine:

I like older people, you know? Even since I was a wee boy I've liked them. They used to play dominoes in a little park near me, in a wee shed, and I used to go and talk to the old guys. And it's a love that has never really left me. And I remember hearing an old guy in Glasgow, arguing with his wife. And it stays with me to this day.

He said, 'Hey, Agnes'.

She goes, 'What?'

'When were we married? What year was it when we were married?'

'1911'.

'1911? Fucking hell... 1911...That was only three years before the fuckin' war came. Aye. We had three bairns. I went away and fought in the war, didn't I? Away fighting in a place I couldnae even fuckin' spell. And there was nights I was a frightened person. But you know what got me through it, Agnes? I knew you were by my side, every step of the way.

1918 they let us oot. Couldnae get a job. Fuckin' unemployed. As we marched proudly intae the Twenties, and the National Strike. I didnae go on strike myself. I was fuckin' unemployed at the time. It wasnae easy. But I got by, with you by my side, every step of the way. Standing by my side.

Intae the Hungry Thirties we went. We managed to get through the Depression without eatin' any of the children. As we proudly marched toward 1939 and another war. They gave me a steel helmet and a big stick and told me to keep the Germans out of Sauchiehall Street. Which I did to the best of my ability. 'Cause I knew that you were beside me, every step of the way.

1945, they let us oot and I couldnae get a fuckin' job. They said I was too old. Struggled forward for five years, got the pension. We soon tired of the Caribbean holidays and the mad parties. Settled down to a life of starvation with occasional trips to hypothermia. Aye. And you by my side, every step of the way.

And here we are. What are we?...Nineteen-fuckin'-eighty-seven! My God. We're in the middle of a recession, whatever that might be. Feels like a depression to me. It might be a typin' error, y'know what I mean? And you're still beside me, every step of the way.

D'you know, Agnes, I was thinkin'... You're a fuckin' jinx!'

Another unlikely influence was an anecdote - probably apocryphal - much-used by British comics, often on chat shows from the 1990s onwards, about Freddie Starr. The standard version was as follows:

One of the funniest stories I heard about Freddie Starr was when he was living in this huge old mansion in Berkshire, on his own, between wives. He'd get really bored, so he would go outside and hang around on this quiet little country lane near his house and wave down random motorists and say, 'Can you give me a hand, please - I need a push'. They'd recognise him, of course, and so they'd get out and follow him as he walked off at a brisk pace, through the gates, past the front of the house, past the garage, and round the back to the garden - and then he'd get on a swing!

Sir Billy developed this into a 2010 routine called (informally) 'The Push':

There's a couple, in bed, in their house. The rain is lashing doon. It's half past three in the mornin', four o'clock in the mornin'. The rain is lashing against the house, the thunder is crashing, the lightning is flashing. All the ashes are happening: crash, flash, lash. And the man is lyin' beside his wife, and he's feeling very comfortable. They've got the duvet, they're lyin' there, comfortable, oooohh, happy-happy. The comfort you get when there's a storm outside the house and you're inside: ooooh, happy-happy.

Suddenly, there's a thunderous knock on the door.

THUD! THUD! THUD! [Muffled sounds of someone shouting]

'Who the fuck...?'

'Shhhhh, just keep quiet, they'll go away eventually.'

THUD! THUD! THUD! [Louder muffled sounds of someone shouting]

'Fuck, I'm not opening the door to that crazy bastar...'

The guy's wife says, 'You'd better open the door. It might be the police...it might be some tragic news...It might be something awful has happened that we should know about. It sounds really urgent.'

'Oh, fer fuck's sake!'

So he gets up. Puts on his jeans, his t-shirt, his slippers. And he goes doon, opens up the door:

[Storm sounds:] Whhhhooooosshhhhkkkkkk!!!

There's a guy standin' there. Sodden from head to foot. Soakin' wet.

'Oh man - you gotta help me! I'm SO stuck! I really need a push! You gotta help me, man, I'm really, really stuck!!'

'You fuckin' tell the RAC! Get hold of the fuckin' AA! FUCK OFF!!!'

SLAM!

'Stuck? Fuckin' stuck???'

He goes back up to bed.

His wife says, 'Who was it?'

'Just some prick who was stuck, says he needs a push! I told him to phone the RAC or AA.'

'Oh, for God's sake, you didn't?'

'Course I fuckin' did!'

'Oh, for God's sake! You've got a short memory!'

'What?'

'Don't you remember just last summer? When we were on holiday? We were stuck on the motorway with a puncture? A total stranger in a rainstorm stopped, and fixed our puncture, and sent us on our way! We don't even remember his name! Now it's our duty to pass that on! It's your spiritual duty as a human being and as a humanitarian act to pass that along! For God's sake!'

'Oh, for fffffffffuck's sake...Okay...'

Gets out of bed, gets into his jeans, puts his t-shirt on, his slippers. Away doon stairs. Opens the door.

WHHHHOOOOOOOOOOOOOOSSHHHHKKKKKK!!!

And the guy's not there anymore.

'WHERE ARE YA?...WHERE THE FUCK ARE YA?? THE GUY WHO'S STUCK AND NEEDS A PUSH? WHERE ARE YA???'

'I'm over here - on the swing!'

Such comparisons as these do not merely highlight the structural simplicity of the essential gags but, more importantly, illustrate just how thoroughly, imaginatively and intimately Connolly could create something significantly richer, more distinct and superior (what the critic Walter Benjamin called 'narrative amplitude'), not only in his own voice but also via his own inimitable comic vision.

The Starr and Manning manipulations, however, were relatively modest by Sir Billy's high standards. There are other instances of adoption and adaptation that really show the full extent of his ability to take a common seed and grow something that feels unique.

In 1970, for example, Peter Sellers told a short comic story - which he attributed to Michael Caine but had in fact already been in circulation for several years - about alcohol and the Pope:

There are a lot of Italian restaurants in London. You know Mario and Franco's? They've got a chain of restaurants in London. And a Cockney went in there one night. And this guy sat down, and he said, 'Oi, Franco: vieni qui'. So Franco came up and he said, 'Yes, what-a would you like?' He says, 'I want a large plate of spaghetti vongole, and a large double Scotch, right?' And Franco said, 'Look, I'm sorry, I got no dispensation for the Scotch whisky, I'm sorry. We've only got here the vino. You can only have the vino. If you want the vino, it s'aright, but I got no possibility for the Scotch whisky, I'm sorry.'

So the guy said, 'Nah, listen: I can't drink that stuff. I can't drink wine, see? An' the reason I can't drink it, I'll tell ya. It's a bit delicate, only that, well, see, I'm goin' out with this bird, an' if I'm on the Scotch, well, it makes me nice an' lively all night, an' if I'm on the vino it's, er, all dahn to larkin, innit? I mean, you know, nuffin' 'appens.' So Franco says, 'Well, I'm sorry, sir, it's-a not possible for me, no, I can't do it, I'd do it if it was possible but I can't. Look, if you don't like this vino you don't pay for it - I can't say more.' He says, 'All right, then, I'll have it, I'll have it.'

So he tries this wine. He's had two glasses and it's knocked him sideways. He's very, very, sloshed, you know? He says, 'Oi, 'ere, Franco: vieni qui. What was in that stuff? What was in that, what was in that wine?' He said, 'Look, I'll tell you somethin' that nobody knows. Shut the windows and the doors, and I'll tell you somethin'. Not nobody knows this thing what I'm going to tell you now: the Pope drinks due bottles of this same wine every day from his life.' The guy says, 'The Pope what??' He says, 'The Pope drinks due bottiglie - two bottles - of this same vino every day from his life.'

He says, 'No wonder he's got them four fellas carryin' him around then!'

The Sellers version was very much like all of the previous, very basic, versions, except that he tweaked it superficially to suit his distinctive gift for comic accents. As a brilliant interpreter of other people's scripts, it was typically well-judged in its self-limitation, and added just enough charm to work as a revision that was worthwhile.

The Sellers version, however, soon faded from most people's memory, to the extent that when Sir Billy seized on the source later on in the same decade, he stamped his own signature so surely on to the material that it struck the majority of his audience as a completely new routine:

This wee thing is about two Glasgow guys who went on holiday to Rome. These two guys were in Rome, and they were going around, being tourists, looking up at all the famous sights: 'Aye, look at that, that's fantastic . . . Look at that an' all, fantastic, I'm intae that . . . I wonder who papered that ceiling, that's fantastic . . .' And the sun was belting down on them: 'Hey, the sun's beltin' doon on me!' 'Aye, we should go an' get a bevvy.' 'Right.'

So, they shot into a wee bar in Rome. And they go right up to the bar and say, 'Hey, Jimmy, give us two pints of heavy.' And the barman says, 'What?' In Italian, like. And they go, 'Two pints of heavy - are you deef or somethin'?' The barman says, 'Look, we don't have "heavy" in Rome. We've got all sorts of clever things, but we don't have heavy. But look,' and he's pointing at all the different bottles, 'you're welcome to anything you see here . . .'

So, they're looking suspiciously at all these unfamiliar drinks. 'Ah, I don't know about any of these things . . . Hey, tell you what - what does the Pope drink?' The guy says, 'Oh, crème de menthe. I've heard he likes a wee glass of crème de menthe every now and again.' 'Give us two pints of THAT, then!'

Their two green pints duly arrive. And they look at the drink for a moment, a bit unsure about it, and then nod at each other. 'Aw, if it's good enough for the Big Yin, it's good enough for me, okay . . .' They pour the whole glass straight down their throats. 'Nae bad - it's like drinkin' Polo mints, in't it?' 'When in Rome, eh? D'you get it? When in Rome and that!' They lick their lips and turn back to the barman: 'Give us another two, there you go! And they're at it all night. Nothing but green pints.

They wake up in the morning. They're in a crumpled heap in a shop doorway. Their suits are all creased and ruffled up and they've peed their trousers and been sick down their jackets. They've been shouting and hugh-ing all night. HEUEGH! And occasionally calling for Ralf: RALF! Hughie and Ralph. HEUUEEGGHH!!! RAAAALFFF!!! And it's green. Green Hughie. Hughie Green?

I'll tell you what, though - just to digress - talking about being sick. How come - this is a great dilemma - how come every time you're sick there's diced carrots in it? How come? Because I have never eaten diced carrots in my life! You can have lamb madras, a few bevvies, and HUUGHHIE!!! Diced carrots. RAAAALFFF!!! More diced carrots. Every time. And sometimes tomato skins as well, even though I don't eat bloody tomato skins! How come? Now my personal theory is that there's a pervert somewhere, with pockets full of diced carrots, following drunk guys.

But back to Rome. Back in Rome these two guys are waking up in the morning. They're rubbing their faces slowly, rubbing their weary eyes. 'Christ Almighty! . . . Ooohhhhh, ma heid! . . . I think I'm wearin' an internal balaclava!' One of them starts rubbing his body. 'Christ Almighty . . . Oohhh, ma body's so sore . . . AAGGHH! I CANNAE FEEL MA LEG!' 'That's MA leg, ya bampot!' 'Oh, thank Christ for that! Jeez, what a fright I got there!' He looks over at his friend. 'How are you?' 'To tell you the truth . . . I feel kind of funny. I think I've had a tongue transplant. This one doesnae seem to fit.'

'Christ . . . and they say the Pope drinks that stuff?'

'Aye. Nae wonder they have to carry him about on a chair, eh?'

That is the kind of adaptation to admire. The comparison reveals the inventiveness of the adaptor rather than merely, or mainly, his initial source material.

It takes the same basic set-up, and the same basic pay-off, that Sellers himself had borrowed, but, once deconstructed and reconstructed, it reappears bearing the syntax, the structure and the soul of Sir Billy Connolly. It is, as always, not the comic material that is unique, but rather the comic spirit that lives and breathes and plays around within it.

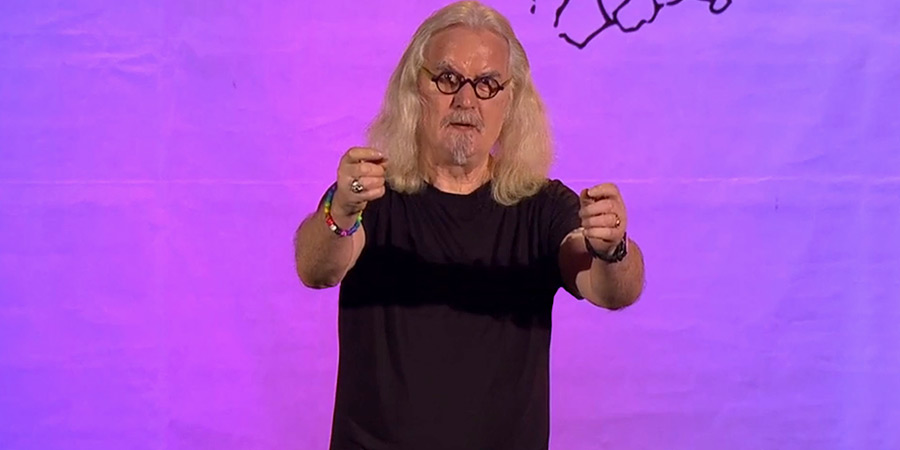

Knowing about such adaptations, therefore, far from diminishing one's respect and admiration for this remarkable performer - this most busy of Baconian bees - surely ought to increase it, because the insight allows us to appreciate more fully the exceptional cleverness of his craft. The same basic stories can pass out of the mouths of many different storytellers before finding the one with the magic to make them really come alive and remain in the mind. No one, in British comedy, has been a better teller, and re-teller, of tales than Sir Billy Connolly.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreBilly Connolly - Tall Tales And Wee Stories

"Coming from Glasgow, it's weird, I don't really tell jokes, like Irish jokes and all that. I tell wee stories. And some of them don't even have punchlines. But you'll get used to it as the night goes on, and on, and on, and on and on..."

In December 2018, after 50-years of belly-laughs, energy, outrage and enjoyment, Billy Connolly announced his retirement from stand-up comedy. It had been an extraordinary career.

When he first started out in the late Sixties, Billy played the banjo in the folk clubs of Glasgow. Between songs, he would improvise a bit, telling anecdotes from the Clyde shipyard where he worked. In the process, he made all kinds of discoveries about what audiences found funny, from his own exaggerated body movements to the power of speaking explicitly about sex. He began to understand the craft of great storytelling too. Soon the songs became shorter and the monologues longer, and Billy quickly became recognised as one of the most exciting comedians of his generation.

Billy's routines always felt spontaneous. He improvised, embellished and digressed as he went: a two-minute anecdote could become a 20-minute routine by the next night of a tour. And he brought a beautiful sense of the absurd to his shows as he riffed on holidays, alcohol, the crucifixion, or naked bungee jumping.

But Billy's comedy could be laced with anger too. He hated pretentiousness and called out hypocrisy where ever he saw it. He loved to shock, and his startling appearance gave him license to say anything he damn well pleased about sex, politics or religion. It was only because he was so likeable that he got it away. Billy had the popular touch. His comedy spanned generations and different social tribes in a way that few others have ever managed.

Tall Tales And Wee Stories brings together the very best of Billy's storytelling for the first time and includes his most famous routines including, The Last Supper, Jojoba Shampoo, Incontinence Pants and Shouting at Wildebeest. With an introduction and original illustrations by Billy throughout, it is an inspirational, energetic and riotously funny read, and a fitting celebration of our greatest ever comedian.

First published: Thursday 17th October 2019

- Publisher: Two Roads

- Minutes: 336

- Catalogue: 9781529361339

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 17th September 2020

- Publisher: Two Roads

- Pages: 336

- Catalogue: 9781529361360

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Two Roads

- Download: 2.62mb

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.