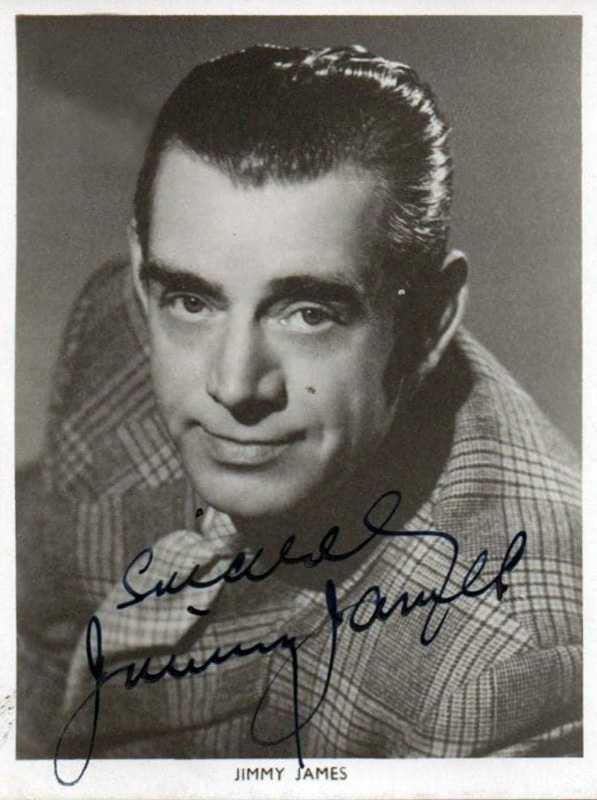

The Comedians' Comedian: The art and impact of Jimmy James

Jimmy James was one of British comedy's great influencers. He wasn't the kind of influencer who goes online and gushes about all the goodie bags they've been given. He was the kind of influencer who, through sheer talent, inspired a whole generation of comic performers. If our comic heritage was displayed as an autographed shirt, his signature would be among the most prominent.

The James Effect would change our stand-up, our sketches and our sitcoms. It would enrich our collective comedy culture. Anyone in Britain with an ambition to make people laugh, who lived when he was working, would study every aspect of his art. He was a one-man academy, an ongoing masterclass, an enduring inspiration.

Making the public laugh is hard. Making one's peers laugh is even harder. Jimmy James managed to do both without ever seeming to strain.

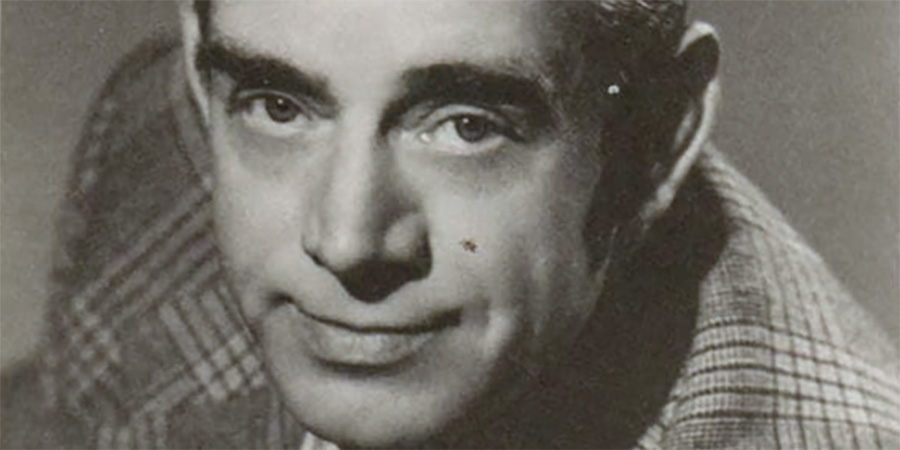

A stocky, barrel-chested little man, whose every feature on his bulldog of a face (the bulging eyes, the poking nose, the protruding lips) seemed to be reaching out to engage with his audience, he played a character who usually found himself trapped between two people, one an idiot and the other an even bigger idiot, whose deceptively banal but essentially surreal chatter, as it sucked him in, gradually made him wonder whether he was a bit of an idiot, too.

He timed lines better than any of his contemporaries; he settled into scenes far more believably than was the norm. Those who knew best, knew that he was the best: the one, and only, Jimmy James.

Actually, to be strictly accurate, he was not quite the only Jimmy James - at least not for a while. There was another comedian called Jimmy James before this comedian called Jimmy James. That Jimmy James, who was active in the 1900s, had described himself as a 'humourist, tambourinist, banjoist and trick and jugging bone solo expert' (the bones in question, in case you're wondering, being percussive instruments played in the hands similarly to the spoons), as well as 'a one-man minstrel show,' and was self-billed as 'The Famous Jimmy James'.

That Jimmy James, however, soon faded away, and the Jimmy James who really did become, and stay, famous was the one who came next. This was the one who was not even really called Jimmy James. He was the one who started out being called James Casey.

The son of a steelworker and part-time musical-comedy performer, James Casey was born on 20th May 1892 in Portrack, Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham. Always inclined and encouraged to perform, he clog-danced outside his terraced home in the hope that neighbours might reward him with a coin or two.

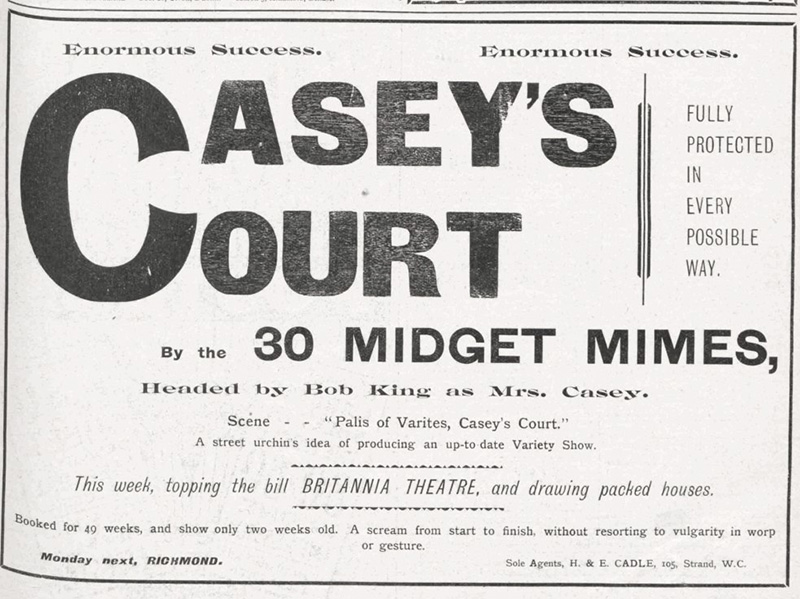

He made his stage debut at the age of ten, winning a boy soprano contest at the Stockton Hippodrome, and two years later, adopting the identity of 'Terry Casey - The Blue-Eyed Boy', he started serving his apprenticeship in a succession of juvenile singing, dancing and comedy troupes, beginning with 'Casey's Court' (an act composed mainly of midgets posing as street urchins), and moving on to Phil Rees's The Stable Boys (a group of youths dressed in riding breeches who sang and danced) and then for Will Netta (the stage name used by his father) in the similarly-themed 'Singing Jockeys' (an eight-strong comedy vocal group).

When his fledgling career was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War, he signed up to serve with the Northumberland Fusiliers on 1st September 1914. His own participation in the conflict, however, was cut short after he was gassed during an attack. Discharged from service on 7th November 1917, his breathing problems (involving damage to his lungs and vocal chords) prevented him from returning immediately to singing, and so he concentrated on comedy instead.

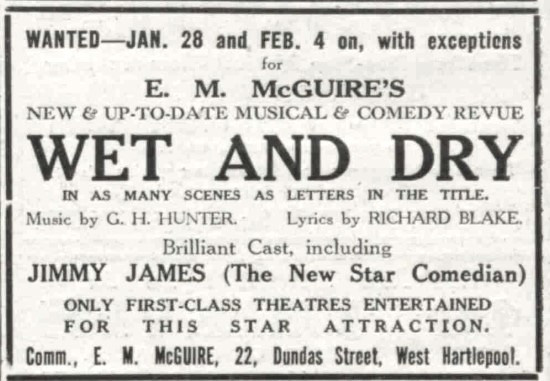

Joining the northern producer Tom Convery's large company of comedians, who toured the provinces in a succession of revues and pantomimes, he now adopted the stage name of Jimmy James (the previous one having retired) and spent the next few years discovering his strengths and weaknesses as a performer while obliged to do everything from stand-up routines to character acting. Improving each year, he was starting, by early on in the next decade, to attract the attention of various other promoters, and late in 1923, after another comic had dropped out of a forthcoming musical-comedy revue called Wet And Dry, James was picked to take his place.

Now billed as 'The New Star Comedian', the show would make his name. Hailed by one observer as 'a comedian who can turn any incident into a laugh', he soon found himself being offered numerous other projects. He had, without any doubt, arrived as a recognised major talent.

One of the striking things about him, even in those early days, was the fact that so much of his performances, though always assured, was actually improvised on the night. He had a rare ability to sink into his on-stage characters so snugly that, within a very loose narrative structure, he could move and speak as the mood took him without ever seeming out of synch. The more the critics praised him, the more the producers craved him.

In 1924, he was signed up, initially on an exclusive two-year contract, to the position of the principal comedian in the company run by the impresario Clara Coverdale. Starring first of all in her sporting-themed revue called 10 To 1 On, James was widely-praised as 'a real comedian who never fails' and a performer who invested a 'rare wit in his every word and action'. Switching rapidly through a range of roles that included an excitable Italian playboy and a henpecked Lancastrian husband, he dazzled in a show that became one of the biggest hits of the next couple of years.

He would follow this with Sidelines - a revue that featured, amongst other routines, a self-contained triptych of sketches (which would later be somewhat clumsily adapted for the 1950 film Over The Garden Wall) that would see him showcase one of his finest comic performances. The opening instalment of these, entitled The First Night, featured his character staggering home, from a long night out, and encountering a policeman near his house, and the last, which was called Sober As A Judge, concerned his desperate attempts to extricate himself from the drink-driven chaos he created in his wake.

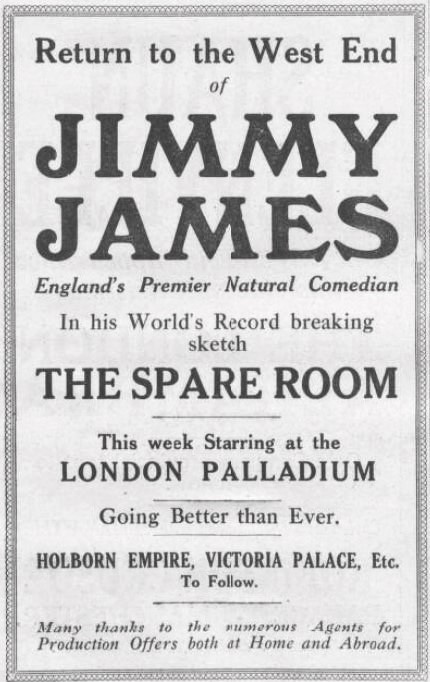

It was the middle moment, however, that would really command the attention of both the public and the critics alike. Written by Dick Batch, it was called The Spare Room, and it followed the awkward efforts of a drunken husband, somewhat dishevelled in a top hat and evening dress, as he staggered home in the early hours of the morning to be confronted by his wife.

This sketch became a comedic tour de force. Although, off stage, he was actually teetotal and a non-smoker, James would come into view each night, through a cloud of smoke, seemingly reeking of booze, and instantly convince the audience that he really was that beer-breathed buffoon with the nicotine-stained fingers.

It was one of the great, and most influential, comic performances of the era. First of all, he went against the acting stereotype of the time and, rather than play someone moving like a drunk, he played a drunk struggling to move as though he was sober, looking like someone slaloming through a crowd that no one else could see. It brought a sense of realism to the role that had never been there before: instead of the usual lolloping limply about, his body was seen to be straining desperately to regain control of various muscles and limbs that were no longer in regular touch with his brain.

The process whereby, rocking as if on choppy waters, he tried to undress, aim his arms and legs into his pyjamas and then find and land on his bed was like some kind of elegant comedy ballet. Each move, each expression and each gasp and grunt was supremely well-timed, and performed so plausibly that the experience of watching the whole scene unfold, as one reviewer put it, 'felt at though one was witnessing it from just inside the shadows'.

One 'straight' actor of note who kept going back to watch James perform the sketch was a young Laurence Olivier, who sat each time in the stalls and stared in wonder at how the comedian varied each step in the sequence, finding new tricks and different nuances on every occasion. Later acknowledging that these and other evenings spent studying James had been a major inspiration for his portrayal of the comic Archie Rice in the 1957 John Osborne play The Entertainer, he described the original performances as 'the most brilliant creation, a genuine theatrical experience'.

This routine alone (and it would be reprised many times due to the enduringly popular demand) would have ensured that Jimmy James would be remembered as one of Britain's most acclaimed comedians, but there was more still to come. There was the box routine still to come.

Introduced shortly before the end of the Second World War as part of a touring variety revue entitled The Merrier We Shall Be, this particular sketch would have an impact and an influence that would last all the way through to today. It featured James bookended by two dozy eccentrics: Hutton Conyers and Bretton Woods.

Hutton Conyers (christened after a village near Ripon in Yorkshire whose name had amused James as he drove past it) was first played by his brother-in-law, Jack Darby. The character sported a mop-topped haircut and a long plain overcoat. Bretton Woods (named after the location of the 1944 international finance conference) was essayed by James's nephew, Jack Casey (later known as Eli Woods). He was a tall, gangling, sad-faced stutterer dressed in an over-tight suit and a check cloth cap.

They would appear together in several routines spread throughout the show. One of them saw James, posing as Lancashire's champion chip maker, attempt to explain to a curious but confused Bretton Woods the noble art of the potato chipster: 'Y'see, you get hold of the potato on the block, y'see, and you grab hold of the handle, y'see, and then it's: On-Pull-Chop! On-Pull-Chop! On-Pull-Chop! Only, get your fingers out quick - otherwise you'll think you've got more chips than you've chopped...' Each one of these sketches, it was reported at the time, elicited an exceptionally positive audience response, and even on some nights standing ovations.

The climax of the trio's collaborations, however, was something really very special. It was 'The Box'.

James would come on to the stage already looking somewhat rattled by his dim-witted acquaintance, Woods, Then Conyers would march on, ready to start a fight, alarming James with his flashes of madness whilst Woods, with a mixture of curiosity and bafflement, listened quietly from the other side.

The routine developed with James, through a mixture of sighs, stares, asides to the audience and muttered exclamations to himself, choreographing the whole thing with such sublime timing, and such subtle but telling reactions, that, no matter how absurd the conversation became, it never, for one moment, seemed as though the collective suspension of disbelief would be strained:

CONYERS: [From off stage] Oi!

JAMES: What was that?

CONYERS: [Striding on stage with a shoebox under one arm] OI!! Have you been putting it about that I'm barmy?

JAMES: Why? Did you want it kept a secret?

CONYERS: Now that's not nice! Someone's been saying that I'm barmy!

JAMES: Well, don't blame me! [Whispers to Woods] I'll keep him talking, you go and 'phone the asylum. Ask them whether they've done a head count lately and are they missing any.

[Woods, blank-faced, stays where he is, open-mouthed and staring]

CONYERS: I heard that! You're the one who's been saying that I'm barmy!

JAMES: No I'm not! Why do you think someone wants to call you barmy?

CONYERS: Well, somebody is! And that's not nice! I'm a well-travelled man, you know.

JAMES: Really? [Mutters to Woods] I wish he'd travel right now!

CONYERS: Oh, I can't travel now, the last bus has gone.

JAMES: You've got ruddy good hearing, any road! Where've you been to on your travels?

CONYERS: I've been all over Africa.

JAMES: I can't say I've ever been there.

[Suddenly distracted, they all look urgently around the stage. None of them looking in the same direction.]

JAMES: Did somebody come on? He got away quick whoever he was. [Turns back to Conyers] Like I was saying, I've never been to Africa.

CONYERS: Oh, you'd love it. I've been to South Africa you know.

JAMES: Have you now? What was your job out there?

CONYERS: Colonial Secretary.

JAMES: Ah. So that's what was wrong.

CONYERS: I was very popular, you know!

JAMES: Oh, well, they're nice people, the South Africans.

CONYERS: Yes, very nice people. And just before I left they gave me a present.

JAMES: Really? What did they give you for a present?

CONYERS: Two man-eating lions.

JAMES: Did they now? Real lions? Did you fetch them home?

CONYERS: Yes.

JAMES: Where do you keep them?

CONYERS: In this box.

JAMES: [Hesitantly] Are they in there now?

CONYERS: Yes.

JAMES: I thought I heard a rustling. [Whispers to Woods] I can see we're going to be here some time - go and get two cups of coffee will you, one with strychnine in, and make that 'phone call while you're about it.

[Woods, still seemingly in a daze, stays rooted to the spot]

CONYERS: Are you tellin' him about the lions?

JAMES: [Humouring him, he turns back to Woods] Oh, he's got two lions in this box.

WOODS: How m-much are they?

JAMES: He doesn't want to sell them!

CONYERS: I've been to Nyasaland as well.

JAMES: Now there's a novelty.

[They're all distracted again: looking around the stage, none in the same direction.]

JAMES: I wish you wouldn't keep doing that! If he comes on again - grab 'im! [To Conyers] I suppose you had a good time in Nyasaland as well?

CONYERS: Oh yes.

JAMES: Yes. They're very nice people, aren't they, the Nyasas.

CONYERS: Yes. They gave me a present.

JAMES: Well, they would. They're very nice people. Er, what was it that they gave you for a present?

CONYERS: They gave me a giraffe.

JAMES: Oh. Did you, er, fetch the giraffe back to England?

CONYERS: Yes.

JAMES: [Mutters to himself while puffing out smoke rings like thought bubbles] I don't like to ask him... [To Conyers] Er, where do you keep the giraffe?

CONYERS: In this box.

JAMES: [Sighing] Somehow I thought you were going to say that! You can't be serious! How can you carry two lions and a giraffe around in a cardboard box?

CONYERS: I tie it up with string.

JAMES: [Whispers to Woods] Make that call - I'll keep him here!

CONYERS: Are you tellin' him about the giraffe?

JAMES: Oh, er, yes. [To Woods] He's got a giraffe in this box! Yes. With the lions!

WOODS: B-b-black or white?

JAMES: [To Conyers] Isn't that nice? He wants to know what colour the giraffe is.

WOODS: N-n-no! N-n-not the giraffe - the coffee! Do you w-want it black or white?

JAMES: Oh good grief! 'Aven't you got it yet? Get whatever they've got - and put some strychnine in mine as well!

CONYERS: Hey - I've been to Kenya as well.

JAMES: Oh yes? You've been all over, haven't you? And did you have a good time in Kenya?

CONYERS: Oh yes. Very nice people, the Kenyans.

JAMES: Of course they are. Very nice people. I bet they gave you a present.

CONYERS: Yes.

JAMES: And what did they give you?

CONYERS: An elephant.

JAMES: Male or female?

CONYERS: No, an elephant.

JAMES: No, y'see, don't you realise that...oh, no, don't bother. I don't suppose it matters to you whether it's male or female.

WOODS: It w-wouldn't m-matter to anyone. Only a-another elephant.

JAMES: I shall have to stop you going to those youth clubs!

CONYERS: I brought it home with me, y'know!

JAMES: Really? [To audience] I hardly dare ask him... [To Conyers] I suppose you keep the elephant in the box as well?

CONYERS: Don't be silly! 'Ow could I get a great big elephant in there?

JAMES: No, no, you're right, it is silly when you come to think of it. Sorry, I was carried away for a moment. [Mutters to himself] I'll be carried away for good before long! [Turns to Woods] Why don't you mind your own business? You couldn't keep an elephant in that box - there's no room!

WOODS: Y-y-you could ask the giraffe to sh-shift over a bit.

JAMES: That's right. You could ask the... - oh, you're as bad as him!!!

CONYERS: No!! You can't keep it in the box - I keep me elephant in a cage.

JAMES: Now that's a relief [To audience] Ohhh, I really am afraid to ask him! [To Conyers] And where do you keep the cage?

ALL: IN THE BOX!!!

It was hailed, quite understandably, as an instant classic. 'Genius,' one critic wrote at the time. 'I thought of the almost uncanny timing Mr James is displaying in his brilliant new act, which may well be just about the greatest he has ever achieved. Surrounded by his two mad stooges, he registers every subtle gradation of baffled consternation, alarm, despondency, worldly cynicism and kindly enquiry. Nothing goes right for him and yet in some odd way he contrives to look splendidly triumphant amid a ruin of surrealist insanity. If this is not comic genius I have never seen it.'

James would continue to perform the routine, with many variations in detail and a succession of stooges, for the rest of his life. A whole generation of young would-be comedians would watch him glide through it on the stage, never wavering from the melodic line of the comedy, always true to his character, always acutely attuned to his audience and its mood, and they would all be entranced and inspired.

Peter Sellers, for example, would cite James as a major role model ('I knew I was in the presence of a master', he said of the time he first saw him live on stage), drawing especially on the older performer's rootedness in the truth of the comic situation. Frankie Howerd learnt much of his own reactive comic touches from the man he considered a mentor, copying the way he won as many laughs from his sighs, scowls and sarcastic asides as he did from his more straightforwardly funny lines. Tony Hancock was another who worshipped the man for the way he mined and managed the comedy from the conversations he conducted with others, with the exchanges in Hancock's Half Hour between Tony, Sid and Bill serving as something of an homage to his hero.

Peter Cook would be similarly inspired by James's clever blend of the surreal with the prosaic. The sketch, for example, that he would write for Kenneth Williams - Not An Asp - was quite openly based on the box routine ('I've got a viper in this box...'), while several of his E. L. Wisty monologues and Pete and Dud dialogues reflected the same Jamesian spirit.

Morecambe and Wise were two others who studied Jimmy James assiduously during their own formative years as performers. 'We appeared with Jimmy lots of times', recalled Eric. 'His way with words and his delivery, but, above all, his mastery of timing, was an example to us all. There never was, nor will there ever be, another Jimmy James.'

They would go on to be particularly indebted to him for two well-known features of their later TV shows. One concerned the celebrated Grieg Piano Concerto routine, and the other involved their famously irreverent treatment of their star guests.

The seed of the former was sewn in the late 1940s when Eric Morecambe saw James perform a sketch in which he struggled to start singing a song in front of a sombre-looking orchestra, whilst chipping away aggressively at the perfectly competent musicians, and conductor, who were waiting patiently for him to get going. First of all there would be multiple false starts, and clearings of the throat, followed by James inquiring with faux-innocence as to the possible culprit who had put him off ('That piano's damp, isn't it?'). Then he would start baiting the conductor:

JAMES: That's an old fiddle, isn't it? An old fiddle, eh?

CONDUCTOR: It's an old master!

JAMES: Pardon?

CONDUCTOR: It is an old master!

JAMES: He's an old - what did you say?

CONDUCTOR: IT'S AN OLD MASTER!!

JAMES: He's an old... - oh, the fiddle, yes, yes, I see.

[Someone whispers an attempted explanation into James's ear]

JAMES: Yes, so did I at first! No, old master, the fiddle...

Eric, along with Ernie, would never forget the routine (which they witnessed on many occasions), and, initially in the 1960s with Hills & Green and later at the start of the 1970s with Eddie Braben, would keep returning to it, adapted for a piano, orchestra and conductor, until, at last, they had crafted something really special (almost) all of their own.

They would also 'borrow' the basics of the box routine for their opening chats with their guests. Eddie Braben - who was also a huge Jimmy James fan - was quick to start writing the kind of dialogue for these triangular interactions that would allow Eric (on most occasions) to assume the directorial role of Jimmy, standing between Ernie and their guest as his two Conyers and Woods-style stooges, driving the comedy on - such as in this exchange with Glenda Jackson:

ERIC: [Muttering to Ernie] There's a drunk just come on from the audience. Leave it to me, I'll get rid of her. [Turns to Glenda] Excuse me, Miss. Or Madam. As the case may be. I'm afraid you can't stop here. Only professional artists are allowed up here in front of the cameras. Go back to your seat - this isn't The Generation Game - please.

GLENDA: I am Glenda Jackson!

ERIC: Oh, ho-ho-ho-HO!!! They all say that! I was with Robert Morley last week - he said he was Glenda Jackson! The way he's walking, I think he is Glenda Jackson!

GLENDA: I am not a member of the audience!

ERIC: [Looks at her close up. Turns to Ernie] She could be right.

ERNIE: Yes?

ERIC: She's sober.

ERNIE: Oh.

GLENDA: Don't you remember me? GLEN-DA!

ERIC: [Puzzled momentarily] Oh...Glen-da! Hey-hey-hey-hey!... [Looks blankly at Ernie, shrugs his shoulders] Er...?

ERNIE: GLENDA!

ERIC: Glendan...Jacklin! The golfer? Show us your putter!

The Grieg routine would actually serve as a double dedication to James's memory, as it was not only built on one of his old routines but also had André Previn join Eric and Ernie as another Jamesian trio:

ERNIE: Could we get in touch with Grieg?

ERIC: That's a good idea.

PREVIN: [Incredulously] You mean call him on the phone?

ERNIE: Call him on the phone - why not?

PREVIN: [Sarcastically] I didn't bring his phone number.

ERIC: Well, it's 'Norway something-or-other', isn't it?

ERNIE: What's the code?

ERIC: 'Fingal's Cave', or something.

ERNIE: I think it's Fingal's Cave.

ERIC: Mind you, you might not get him. He could be out skiing.

'Whenever you hear me using any of your dad's material,' Morecambe would tell James's son, 'there are two reasons. One is because it's a kind of tribute, and the other is because it's very funny. But mostly,' he added, 'it's because it's very funny.'

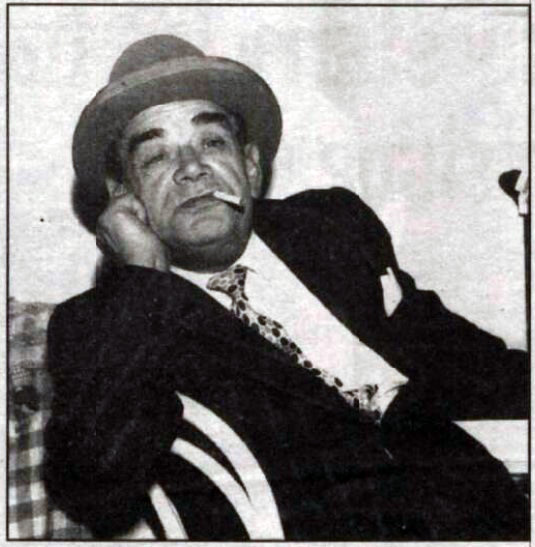

Another, but more unfortunate, way in which Jimmy James influenced his fellow performers was through his struggles holding on to his money. If ever any budding entertainer needed a salutary lesson about the importance of taking proper care of the business side of the profession, they only needed to study the chronically shaky state of Jimmy James's economic position.

He not only, at his peak, earned a great deal of money; he also lost a great deal of it, too. Nothing much mattered to him except making people laugh. Nothing much made sense to him, either, except making people laugh. He was, in general, utterly hopeless at managing his personal finances (he didn't even have a bank account), and at several stages in his life he struggled to pay off the massive debts he kept accumulating without ever appearing to notice their creeping presence.

Addicted to gambling, he lost large sums to the bookies (during one summer season in Blackpool, he took to having a haircut every day after discovering that the local barber accepted bets on all the local races, and once won £28,000 only to squander it all a few days later) as well as too much for comfort on card games and random wagers.

The cash crises were compounded by the fact that he was also generous to a fault. A notorious soft touch for any hard luck story, he was always ready to help out a stranger, as well as numerous charities, friends and family, even when he barely had enough to keep his own affairs in order.

His career, as a result, was increasingly undermined by worries about money, and his health, both physical and mental, would also suffer because of the stress. These problems had been played out in public since 1939, when it was reported that he had been arrested, straight after stepping off the stage at the Lewisham Hippodrome, for non-payment of tax. He spent the night in Brixton jail until the £380 he owed had been paid. After that unhappy incident, the saga of his financial crises would run alongside the success story of his stage act throughout the rest of his life and career.

He would be declared bankrupt no fewer than three times over the years: in 1939, 1955 and then again in 1963. 'I have been a bit of a fool', he said at the last of those court hearings. 'I have been too generous and given away, unthinkingly, the money which should have gone to the tax collector.'

His popularity, however, was never deflated no matter how drained his savings became. The performers who played his stooges would change (entirely amicably) a number of times, but he continued to shine in the sketches that they did. There was never any danger of him sticking too rigidly to the script, because he never really used one - 'I'm an old-fashioned comedian', he liked to say. 'I loathe scripts' - and his peerless ad-libbing ability ensured that many fans went to see him more than once in the same week, so sure they were of not getting the same show twice.

It was, indeed, all the more exciting when he seemed to be tiring of an over-familiar section of a sketch, because that was the moment when his improvisatory skills really sparkled. As the Hollywood star Mickey Rooney once remarked, somewhat ruefully after having to follow him on stage, 'That guy Jimmy James does every trick in the goddamned book!' That was what made people keep coming back to watch him over and over again.

James also, somewhat belatedly, succeeded in radio. His instinct for mischief had undermined his chances earlier on when a BBC producer asked, 'Exactly what do you do in your act, Mr James?' and he had replied, 'I'm glad you brought that up. It's been worrying me for years'. His continuing theatrical triumphs, however, kept him as an obvious candidate for the wireless, and in 1951 he was given his own BBC radio series: Home, James.

A fairly formulaic variety show, with comedy and musical guests linked by monologues and sketches by James himself, it was aired on the Corporation's northern regional service and worked well enough to rise quite rapidly through the ratings, even though it hardly suited his instinct for improvisation. He also appeared often on the national network, guest-starring in numerous popular shows.

In 1952, to build on his stage and radio fame, James was awarded a short BBC TV variety series called Don't Spare The Horses. Another variety show, featuring not only James and his usual stooges but also such guests as his old fans Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe, it was shown at peak time, once every month on Saturday nights, and further extended his following around the country.

There was also, at long last, the honour of an appearance on the Royal Variety Performance the following year ('After thirty years on the stage', he said at the time, 'I had begun to think that the [annual event] had passed me by'), as well as, during 1955-6, a BBC TV version of his old radio show Home James. He took great pleasure, as his career continued, to groom and guide a new generation of up-and-coming comic performers, such as Ken Dodd, Joan Turner, Jimmy Clitheroe, Roy Castle, Larry Grayson and Jon Pertwee.

The one disappointment, during his later years, was the poor reception of his sitcom. Called Meet The Champ, it was written by Sid Colin and featured James as the manager of a gormless young boxer, played by Bernard Bresslaw. It had been quite an expensive programme to make (Bresslaw had been lured over from ITV with one of the most lucrative contracts that the BBC had so far offered to a comedy performer, and James, too, was well-rewarded for his efforts), and one that was, by the standards of the time, heavily hyped.

Broadcast during September and October 1960, it did not show James at anywhere near his best (compromised by the need to stick to a script, his performances were further undermined by his increasingly poor health), although he still did enough to impress most of the critics ('It's not difficult to see', wrote one, 'why he's one of our best loved comedians'). The show as a whole, nonetheless, was slated for its slow pace, weak humour and reliance on wordiness at the expense of action ('insipid', 'amateurish', 'under-rehearsed' and 'lamentable' being common phrases in the critiques).

It did not bother James too much. He remained busy in the best theatres, still playing to warmly appreciative audiences, and still breaking the odd box office record. He was also proud at the progress of his son, James Casey, who, aside from sometimes appearing alongside him, was now one of the BBC's top radio producers at its northern base in Manchester, overseeing shows such as The Clitheroe Kid.

Casey would soon be obliged to assume more of a managerial role in his father's career as his financial and health problems once again began to grow. He did what he could to help pay off some of the many debts, and lent him his flat in Blackpool to rest between engagements. All of the anxiety, however, soon took its toll.

In 1964, after suffering a major heart attack, followed by a stroke, while starring in a well-received summer season in Skegness, Jimmy James was forced to retire from show business. In an emotional tribute written at the time of the announcement by his old stooge and nephew Eli Woods, who hailed him as 'the King of Comedy', it was remarked: 'George Bernard Shaw once said: "To appreciate true genius I should have an audience of philosophers". To appreciate the true genius of Jimmy James he should have had "An Audience of Comics".'

It was a sign of how profoundly James was appreciated within his profession that, the following March, the impresario Bernard Delfont organised the biggest benefit event so far for a British performer in order to raise funds for his retirement. Among the many celebrities who were quick to commit for no fee were Peter Sellers, Frankie Howerd, Bruce Forsyth, Bob Monkhouse, Ronnie Corbett, Dickie Henderson, Peter O'Toole, Michael Caine and Barbara Windsor.

Entitled A Golden Night Of Comedy, it raised several thousands of pounds for the ailing comedian, who, though too ill to attend, was deeply touched by the gesture. A few months later, he and his wife, Emmy, started to make plans to spend the rest of their days back in his hometown of Stockton-on-Tees.

Sadly, that never happened. On 4th August 1965, Jimmy James died in his son's home at Hampton Road, South Shore, Blackpool. He was seventy-three.

The tributes were many and heartfelt. One comedian after another took the chance to express their sadness and acknowledge their debt. In a very competitive profession, there was, on this occasion, complete consensus as to the extent of their loss.

Jimmy James had, it was agreed, not just been very funny; he had also been formative. His legacy was left to continue to spread throughout the comedy world.

Eric Morecambe, one of his greatest fans, as well as one of the very few to eventually reach up to his own rare level, put it best when he said: 'He had that thing that broke all barriers with an audience. He was loved by the pros - professionals - and loved by the audience. Now, Jimmy had this fantastic gift, that he was liked and loved - this is an important word - was loved - by both. One of the few comedians that all the comics used to stand on the side and watch. One of the greats.'

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreOver The Garden Wall

In Over The Garden Wall, a working class couple (Jimmy James and Norman Evans) are planning to give their only daughter and their new GI son-in-law a right Northern welcome. As always though riotous trouble starts to flare up when a young man starts to flirt with James and Evans daughter!

Over The Garden Wall put the two comic geniuses together as a one of the funniest fictional husband and wife teams to grace a British screen and inspired Les Dawson's famous female impersonation.

First released: Wednesday 28th March 2007

- Distributor: Odeon Entertainment

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 94

- Catalogue: ODNF068

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.