The subtle sitcom skills of the one and only Sydney Lotterby

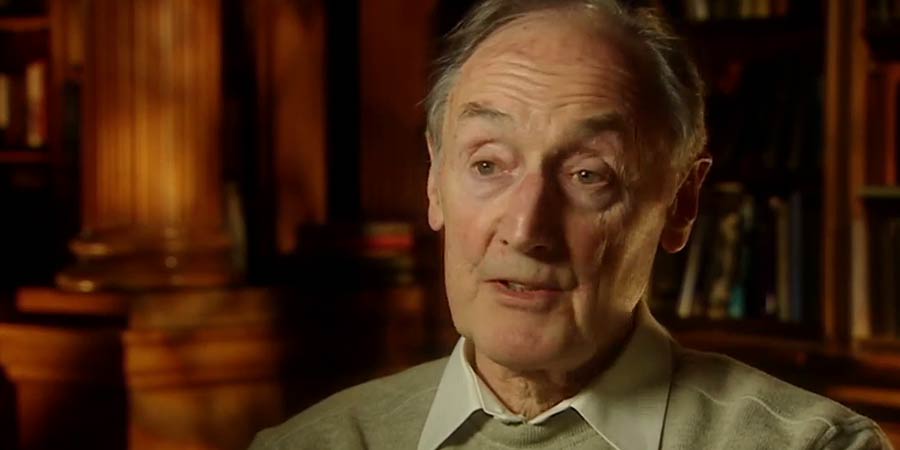

If anyone, after Duncan Wood, deserved the title of doyen of the British sitcom, it was surely Sydney Lotterby. During the course of an exceptionally long and distinguished career, he presided over many of the genre's best and most successful productions, including Sykes, The Liver Birds, Up Pompeii!, Some Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em, Porridge, Open All Hours, Last Of The Summer Wine, Butterflies, Ever Decreasing Circles, As Time Goes By and Yes Minister. For more than forty years, whenever the BBC wanted a well-made sitcom, the first thought usually was: 'If you see Syd, tell him'.

If he had been working in American television, he would almost certainly have been honoured by multiple black tie tributes, subjected to epic commemorative Television Academy interviews, showered with all kinds of lifetime achievement awards, patted very publicly on the back by the Producers' Guild and celebrated in countless articles and the odd biography, and he would have spent his later years in sun-kissed luxury as one of the industry's living legends.

As he was British, however, he - like other highly accomplished BBC producers - rarely got much more eye-catching credit for his achievements than the standard showing of his name at the end of each show. He did manage to get four BAFTAs (and to put this into some kind of perspective, that's ten fewer than Ant and Dec, at the time of counting, have accumulated so far) but he deserved so much more for all the fine work that he contributed.

It might be said that, in this respect, he did not help himself, given that he was guilty of that most heinous modern sin of humility - on the rare occasions when he was invited to speak publicly, he always downplayed his own successes by insisting that they came about simply through 'luck - absolute luck' - but talent should be recognised and respected even when the talent-holder does not shake you by the shoulders and shout in your face 'recognise and respect me' until your eyes sting and your ears bleed (if you're currently in the media, that's probably worth popping on a Post-it Note). What ought to be evident just from looking at the craft of making sitcoms is that there is still an awful lot of Lotterby left in the method of the medium.

The son of a shopfitter, Sydney Warren Lotterby was born in Paddington, west London, in 1926, and grew up in Edgware, Middlesex. He left school (Kingsbury Grammar) at fifteen and worked as a technical storekeeper for the BBC at Broadcasting House. Following the completion of his National Service, in the Royal Signals (for whom he taught radio theory at Catterick), in 1948, he was again drawn to the BBC and a career in programme-making.

Training as a cameraman ('I'd had enough of sound') first at Alexandra Palace and later at Lime Grove studios, he eventually progressed, in 1957, to the supervisory role of technical manager ('most of us were still so young and silly', he would tell me, 'that we'd sometimes do childish things like cue a presenter by squirting at them with a water pistol!'). Transferred in 1958 to the Light Entertainment department, he then served as a production assistant (gaining invaluable experience working under Duncan Wood, who, with his use of multiple cameras, close-ups and fast-paced editing, was by far the most progressive sitcom director of the time) before becoming a fully-fledged producer/director in his own right.

Although perfectly competent at covering several different genres (including popular music shows such as Twist! in 1962 and the talk show Dee Time in 1967), he found himself working more or less from the start on comedy shows, including Charlie Drake's It's Up To You (1960) and the light-hearted panel show Does The Team Think? (1961). The beginning of his sitcom career, however, started in 1963 when he took over from Dennis Main Wilson as the director of the Eric Sykes and Hattie Jacques vehicle, Sykes And A....

The show had already been running for a couple of years, but Lotterby immediately impressed Sykes with his ability to picture quickly the dynamics of key scenes, the quiet efficiency of his technical organisation and, perhaps most of all, his readiness to work with the actors until they understood precisely how each set-up could and would be filmed. Under his control, the show would go on to win plenty of praise both inside and outside of the Corporation, and Sykes ended up being so grateful that he wrote to the bosses at the BBC to urge them to recognise Lotterby as one of the best young directors of comedy that they had.

It would prove to be a vital shot in the arm, because in 1964, shortly after finishing work on Sykes and while making The Graham Stark Show, Lotterby had taken the poor reception of this latest programme so personally that, by his own admission, he suffered a 'mini-nervous breakdown', had to take a long break from work, and seriously considered abandoning his career. The support of Sykes, at that stage, helped him fight his way back to health, start recovering some self-confidence, and return to programme-making.

The recommendation certainly seemed to work internally (where Frank Muir and Denis Norden, shortly before stepping down from their position as the BBC's comedy consultants, had been quick to echo Sykes's encomium), because, for the rest of the decade, Lotterby was treated with a growing sense of trust as he moved from one successful series to the next. 'Step by step,' he would tell me, 'I felt I was getting back into it and doing a better job of it.'

His work on Alan Bennett's On The Margin (1966) proved particularly noteworthy. Featuring satirical sketches and monologues as well as songs and poetry - all driven along, according to one reviewer, 'at a spanking pace' - the show attracted enormous critical acclaim, winning the Royal Television Society Award for the Best Television Comedy of the Year, and Lotterby's reputation was certainly boosted by all the positive coverage.

It was indeed becoming increasingly evident within the industry that his calm and good-natured professionalism (along with his dry wit) was winning him the faith and affection of many comedy writers and performers, including Marty Feldman - who teased him in no fewer than three sketches for the At Last The 1948 Show: 'The Four Sydney Lotterbies', 'The Return of the Four Sydney Lotterbies' and 'Sydney Lotterby Wants To Know The Test Score' (all 1967) - and John Cleese, who would go on to name one of the characters after him in his 1997 movie Fierce Creatures.

People wanted to work with him, because they knew that he would respect them, listen to them as well as talk to them, and help them to improve. He was strict when he needed to be, and relaxed when he felt it was right to be, and, rather than just issue orders, he was always ready to engage with his cast in a spirit of mutual support. Most important of all, he was not one of those producer/directors who would force each individual project into a single fixed format and style; on the contrary, he would feel his way into a new set of scripts, do his best to understand what the author was striving to achieve, and then collaborate with them to bring that special vision to the screen.

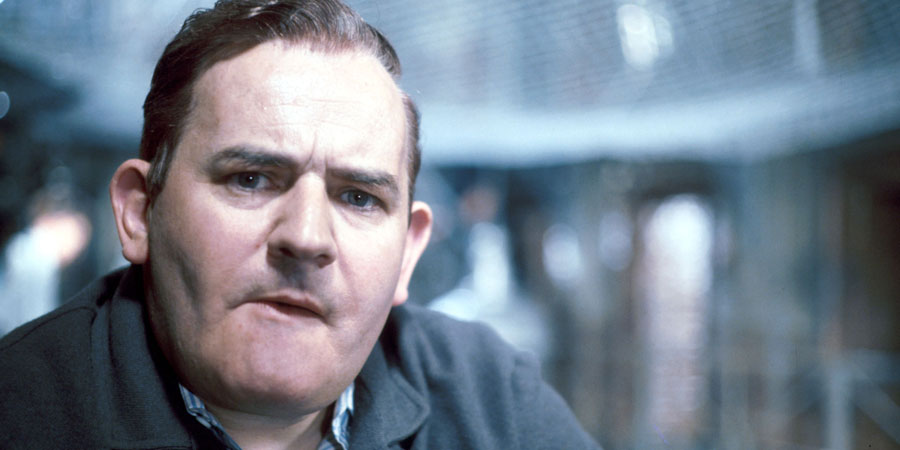

No comedy figure would come to appreciate this collaborative attitude more than Ronnie Barker. He had first worked with Lotterby, very briefly, back in 1964, in an episode of Sykes And A... (Sykes And A Log Cabin), but it was during 1973, when Lotterby oversaw the collection of potential sitcom pilot episodes that went out under the umbrella title of Seven Of One, that Barker really started thinking of the producer as his favourite collaborator.

Seven Of One served, in effect, as the two men's private showreel for each other. Lotterby could watch Barker demonstrate his versatility as an actor, moving each episode from one character, and style of comedy, to another, while Barker could watch Lotterby create a succession of distinctive and insightful contexts in which each character could flourish. It was, as a result, the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Two separate Barker/Lotterby sitcoms emerged fairly swiftly from Seven Of One: one was Porridge (1974-77) and the other was Open All Hours (1976-85). In both cases, Lotterby was perfectly attuned to the moods and methods required.

For one thing, he understood what the two sitcoms had in common: namely, that they were both set in prisons, but in Porridge it was literal while in Open All Hours it was figurative. Norman Stanley Fletcher was stuck in a prison of someone else's making; Arkwright was stuck in a prison of his own making. This meant that both situations could, up to a point, be staged the same way: the people coming in and out of Fletcher's cell were his fellow inmates, whereas the people coming in and out of Arkwright's shop were his local customers, but the dynamic was basically the same.

In terms of pacing and atmosphere, on the other hand, Porridge needed to be steadier and more sedate, because there was an air of familiarity and fatalism about Fletcher and his friends (and foes) inside, whereas Open All Hours needed to be edgier and more erratic, because Arkwright was forever scheming for new ways to survive and thrive, and there was always the option of featuring different customers in each episode.

Lotterby thus collaborated carefully with Barker, and the respective writers (Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais for Porridge, and Roy Clarke for Open All Hours), on the two shows, ensuring that each one's comic potential could be realised as organically, and logically, as was possible. He was also excellent, as a director, at managing the rehearsals - making sure not only that Barker and the others were reaching the right standards, but also calling a halt long before things started to go stale - and at filming in the necessarily confined conditions ('He found every possible way to shoot two people in a small cell', Dick Clement would say admiringly. 'He shot it brilliantly and never missed a trick').

Lotterby also did his job very effectively as a producer, dealing with the usual range of practical challenges that always came with preparing for a new project. In the case of Porridge, for example, he ensured that all the interiors of the fictional Slade prison were rigged up in just a day and a half, but, after the first series, he also spent plenty of time trying to negotiate with the Home Office for permission to film 'one or two brief sequences against an authentic prison backdrop' (in this instance he was a victim of his own professionalism, because the Home Office replied by saying that he had already recreated prison life in Britain so effectively that 'we do not understand the apparent need to use a real prison').

He was similarly assiduous when preparing for Open All Hours. He had to battle with his bosses over an attempt to stop him stocking Arkwright's shop with recognisable products because of the fear of the BBC being accused of product placement. 'It's set inside a SHOP!,' Lotterby kept telling them. 'Shops have things in them! Things that are sold! It's got to look realistic! I can't have him standing in an empty shop, or a shop full of distractingly fake brand names!'

Lotterby eventually got his way. It was decided, after discussions with the relevant internal authorities, that it would be 'editorially justified' for the shop set to have actual brands on display, on the grounds that it had a right to 'reflect the real world', so long as verbal references were avoided whenever possible and close-ups of particular products were resisted.

There were other challenges to overcome when it came to location shooting in South Yorkshire, at the chosen site of Lister Avenue in the Doncaster suburb of Balby. Lotterby found the ideal location to serve as Arkwright's shop: a hair stylist's called Beautique situated at number 15. It was not quite so straightforward, he would later tell me, when he ventured across the road to arrange to use the property directly opposite at number 34:

I'd got myself a sheepskin coat for the occasion, because it was very cold up there. And when I had to choose Nurse Gladys's house, I went along to the place that I'd thought, 'This is the one,' but when I knocked on the door and rang the bell I couldn't get any reply. So I thought I'd better try the next house and see if they know where their neighbour is, so I knocked on that door, and again I didn't get any reply. And I must have gone to about five or six houses in a row, until it seemed as though I was now miles away from the one opposite the shop, when one person finally answered the door. And I said to them, 'I can't get any replies,' and they said, 'No, well, they think you're the tallyman!' They'd all been in hiding!

Lotterby also had to deal with the odd stray member of the public during filming. There was, for example, one elderly local who used to wander into the shop every morning, when it was set up as Arkwright's, in order to buy a box of matches (Lotterby simply arranged to have someone hand him a box each time and send him back out on his way), while on another, mercifully isolated, occasion a large middle-aged stranger interrupted a night-time shoot by brandishing a bread knife and shouting unintelligibly (Lotterby arranged for the crew to bundle him off to a safe distance while he called the police and then calmly completed the scene).

He also had excellent man-management skills when it came to dealing with the actors. With Ronnie Barker, for example, he soon arrived at a method that suited both of them very satisfactorily. 'If I was getting ready to film a particular scene,' Lotterby would tell me, 'and [Barker] would come over and say, "How are you going to shoot this?" I'd tell him, and explain why I was going to do it that way. And then - because he was a very intelligent man - he might well say, "But don't you think it would be better if we shot it this way?" and he'd explain how and why. So I'd always reply, "I'll tell you what - why don't we shoot it both ways, and then in editing I'll see which is best and I'll use that one?" And he was happy enough with that. And if it did turn out that his way was indeed the best, of course I was happy enough to use it.'

That was Sydney Lotterby: unflappable, professional, completely lacking any excess of ego and always ready and willing to do the right thing. In every aspect of the production process, in whatever circumstances, he displayed excellent judgement, and everybody involved saw it and appreciated it.

Probably the only notable person who didn't seem to appreciate it, at least in a very specific situation, was that other legendary sitcom stalwart, Richard Briers. Lotterby and Briers worked together on Ever Decreasing Circles (1984), and, for the first couple of series, the partnership seemed as positive as all of the previous ones had been. Then Lotterby was called into his boss's office and told that he was 'not giving enough direction to the principal actor'. He was promptly replaced by Harold Snoad.

Neither man, at least in my own experience of talking to them, was ever keen to open up about the matter, although Briers, on the couple of times that we did touch on the subject, seemed genuinely pained by the memory, while Lotterby merely sounded shoulder-shruggingly fatalistic. Briers - an inveterate worrier when it came to his work - did once seem to imply (or perhaps I merely inferred) that when news first reached him (towards the end of the filming of the second series) that Lotterby was about to take on the additional responsibility of producing another Esmonde and Larbey sitcom, called Brush Strokes (it would make its debut the day after the start of the third series of Ever Decreasing Circles), he was somewhat anxious about the potential distraction, but, whatever the full truth of their differences, it was certainly a unique incident in Lotterby's otherwise remarkably successful career.

He would go on from strength to strength, investing his expertise in such sitcoms as Yes Minister and Yes, Prime Minister, One Foot In The Grave, May To December, The Old Boy Network, Last Of The Summer Wine and As Time Goes By. Retiring from the BBC in the mid-1980s, he continued making programmes (still mainly for the Corporation) as a freelance until the first few years of this century.

It was never difficult to appreciate what Sydney Lotterby put into a sitcom if you knew where to look, because, if you did know where to look, you knew that there was nothing to notice.

You engaged with the characters and you identified with the situation. You were never distracted by circling camera shots, unusual angles or eye-catching editing.

'If the picture is too interesting,' he said, 'you might not pay enough attention to the dialogue. And if the picture isn't interesting enough, you might start to find some of the dialogue a bit dull. So you need to get the balance right. The director's job isn't to distract, it's to ensure that you're not distracted.'

Lotterby always brushed over his own tracks. He fussed over the form, and then he let you focus on the content. No other producer/director did that more effectively, or smoothly, than he did.

He had a love-hate attitude towards the studio audience. On the one hand, he loathed the artificiality that came with having to do without the fourth wall, and did his best to rebel against it. Rather than, for example, accept the traditional sitcom convention that obliged all of the relevant characters to sit and converse, quite unnaturally, on the same side of a table so that they all faced the camera, Lotterby often insisted on filming one or two figures from one side, and then announced to the audience: 'I'm terribly sorry but you're going to have to see this scene again while we film it from the other side' (and, knowing that they would not laugh as much the second time around, he would then distribute the laugh track so that all the shots were covered).

On the other hand, he accepted that, in spite of the limitations that their presence sometimes caused, the studio audience contributed something special to the atmosphere. 'The actors rise to it, they find more energy and confidence and sharpness, they really do. And laughter is infectious. So, although I always did hate the three-wall set, I had to put up with it most of the time.'

If Sydney Lotterby had a weakness, it was arguably his disinclination to explore properly the art of physical comedy. Physical comedy can be wonderfully clever, subtle, natural-looking and very, very funny (if one doubts it, and the likes of Chaplin, Laurel and Keaton now seem too remote, then just look at David Hyde Pierce in Frasier), but Lotterby shunned it whenever possible.

The main reason for this, at least during the latter half of his career, seems to have been his unhappy experiences when working with Michael Crawford on the third series of Some Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em in the mid-1970s. The problem was that Crawford, as the hapless and accident-prone Frank Spencer, was such a gifted performer of stunts that, when the more elaborate ones won so much laughter and attention, he became obsessed on bettering his own efforts, and then the stunts, at least in Lotterby's eyes, started taking over the show.

There was the famous roller-skating scene where Frank is seen whizzing underneath an articulated lorry; and the one where Frank ends up in a wardrobe that then rolls down a flight of steps; and the one where the Spencers' Morris Minor is teetering on a cliff edge, with Frank hanging precariously from the bumper. These were all before Lotterby came on board (when Michael Mills, as adept at filming slapstick as he was sophisticated comedy, was still at the helm), but that meant, on arrival, that he was dealing with a star who was now even more ambitious when it came to doing these daring and elaborate routines, and the director felt as though he was repeatedly being obliged to break away from filming a sitcom in order to stage and record some complicated stunts (in the first episode alone, this would involve making parts of a terraced house fall apart, and finding a safe way for Frank to be hit by various items of flying furniture, emerge from a tub of hot tar and crash through a bedroom ceiling while holding a live cat).

'I didn't like the physical comedy,' he would say. 'I prefer more character-based comedy, like Last Of The Summer Wine and Porridge. When you are doing special effects, if it goes wrong, you have to do it all over again and the day may be wasted. The pressure is incredible.'

It was a shame that his time making Some Mothers seemed to make him equate all the types and tones of physical comedy with Crawford's acrobatic excesses, because, as a director, it meant that he was overly suspicious of so many perfectly legitimate kinds of visual characterisation and comedy. It sometimes took away a potential change of pace and expression from his sitcoms, which, while never seriously harming the shows that he made, arguably did slightly diminish the potential richness of the odd scene here and there.

His many strengths, however, more than made up for this isolated weakness. Lotterby's sitcoms were always excellent in terms of dialogue, acting, interacting, intimacy and the general comic mise en scène. They cared about their characters, and they made the viewers care about them, too.

Those moments when Fletcher and Godber, stuck in their cell and perched on their bunk beds, rambled away to each other before the punchline hit home; or when Martin Bryce seems almost to melt, like a neglected Mr Whippy ice-cream, in the presence of Paul's relentless sunniness; or when Jim Hacker's eyes dart helplessly about like figures lost in a maze while Sir Humphrey's monologue drones on - these are all authentic Lotterby moments, moments when a sitcom's trapped relationship is shown as close up and personal as any TV screen will ever allow.

Sydney Lotterby was, by disposition, more akin to a character actor than a star. He never did anything to show off himself. What he did was always to show off the sitcom, the grown-up sitcom, for the full entertainment of the audience. That attitude, and that art, was, and remains, a masterclass in ego-free and public-pleasing programme-making.

When he died, on 28th July 2020 at the age of ninety-three, the BBC's then-Director-General, Tony Hall, took the trouble to mourn his passing, saying that he would be 'hugely missed' but had left behind 'a true legacy of laughter'. While he was alive, however, Lotterby was often amused to be reminded how many people within the BBC took him so much for granted that they seemed only vaguely aware that he really existed.

When, for example, the Porridge sequel, Going Straight, was cancelled after just one series, Lotterby, encouraged by countless viewer requests for further episodes, decided to write a polite letter to someone very high up in the BBC, urging them to give the show another chance. He listed all of the positive points from the episodes that had already been screened, he stressed how good the reaction from audiences had been, and he also suggested the ways - such as opening up the situation and bringing in new characters - that a second series could develop in a natural and worthwhile direction. The letter ended by asking 'Why don't you bring it back?' and he signed it 'Sydney Lotterby'.

A week or so later, he received a reply. 'Dear Mr Lotterby,' it read, 'Thanks for your letter. It was interesting. It's always interesting to hear from a member of the public.'

As nice, albeit brief, as that 2020 BBC tribute from Tony Hall was, therefore, the Corporation can and surely ought to do quite a bit better. Sydney Lotterby did, after all, do an awful lot for that broadcaster, and did all of it quite brilliantly.

Some kind of suitable memorial is required. A plaque at one of the BBC's most sitcom-oriented studios would have been apt, if only the Corporation had held on to such buildings, but perhaps BBC Studioworks can still find an appropriate place. A multi-media Sydney Lotterby Production Archive, for the training of future sitcom-makers, would also be welcome, as a means of ensuring that neither his name nor his achievements will ever be forgotten.

Sydney Lotterby did like to say that it had all been 'luck', but while he was right about the good fortune he was wrong about its recipient. It was not him - it was us.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more