Strained Relationships: Bewes & Bolam

The death in November 2017 of Rodney Bewes elicited yet another wave of media interest in the fact that he and James Bolam, his Likely Lads and Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads? co-star, had not spoken to each other for nearly forty years. The truth, however, is that this kind of enduring enmity between sitcom stars is surprisingly common. The two people, on the screen, most responsible for serving as the bricks and mortar of the production often seem like the ones, behind the scenes, who are most set on rendering it into rubble.

There is simply no necessary correlation between on-screen chemistry and off-screen friendships. Sometimes, actors who get on famously in real-life discover, inexplicably, that there is no palpable on-screen rapport, and, conversely, sometimes actors who have no connection off-screen seem to 'click' in front of the cameras.

It is actually the latter equation that has been most evident throughout the history of the sitcom. While audiences may want to believe that the warmth between two actors on screen is genuine, there is, surprisingly often, not much more than icy indifference, if not fiery dislike, behind the scenes.

The Bewes-Bolam relationship is indeed a case in point, because - rather than in spite - of the fact that it is actually rather more complex than either actor has ever admitted.

According to Bewes - who is the only one of the two to have discussed the matter publicly at any great length - the actors (who appeared together in not one but two hugely popular BBC sitcoms, the first running from 1964 to 1966, and its sequel from 1973 to 1974, as well as an above-average cinema spin-off two years later) were firm friends until one fateful press interview in 1977.

Bewes, whose wife Daphne had recently given birth to triplets, recalled the moment when Bolam's partner (the actor Susan Jameson) revealed to him during a routine car journey that she, too, was now pregnant: 'James,' she was alleged to have said, 'you know Daphne had three babies at once... well, I'm just having the one'. The shock, it was claimed, was so great that Bolam almost veered off the road and just missed crashing into a lamp post.

It was, as far as Bewes was concerned, a perfectly innocuous and amusing anecdote ('It wasn't a nasty story,' he later protested, 'it was a nice story'), and, he claimed, Bolam had laughed about it originally when sharing it with him. When, however, Bewes belatedly realised that his intensely private co-star might be upset at seeing it confirmed in print, he rang to explain himself and apologise. According to Bewes, his friend listened silently and then slammed the receiver down, and never spoke to him ever again.

It was only on the occasion of Bewes's death, after countless one-sided re-tellings of the sad story, that Bolam, reluctantly, finally responded, denying that any rift had ever existed. 'There was no fall-out at all, as far as I was concerned,' he said in a brief radio interview. 'We worked together very happily and very well, enjoyed each other's company, and when we finished, we finished.' He added: 'This is what happens in acting. You work with people, you get to know them, you like them, we have a great time, and the job finishes and you go off, and it all starts again with other people, and you can't keep contact with everybody that you know.'

Both accounts, however, were more than a touch disingenuous. Contrary to Bolam's insistence, there had indeed been a 'fall-out'; but, contrary to Bewes's repeated claims, the fuse to it had been lit long before the sudden publication of that one indiscreet anecdote.

Part of the problem stemmed all the way back to when they first started working together in the mid-1960s. Just like the characters they had been picked to play in The Likely Lads - Bolam the round-shouldered, downbeat and cynical Terry Collier, Bewes the upright, nervy and aspirational Bob Ferris - the two actors seemed an odd sort of couple, but whereas Terry and Bob had an emotional bond borne of a shared past, Bolam and Bewes had little at all to hold them together.

Although they came from similar lower-middle-class northern backgrounds (Bolam in Sunderland, which in those days was part of County Durham, and Bewes in Bingley, West Yorkshire) and were of a similar age (Bolam, when the show started, was twenty-nine and Bewes twenty-six), they were very different in terms both of personality and attitude.

The fair-haired, skinny, sloped-shouldered and sad-eyed Bolam (who always looked as though he had just been coaxed out from a very cold room where the ceiling was far too low) was a reserved, taciturn, relatively unassuming character who, while never suffering fools gladly, was generally easy-going on a set, but liked to maintain a strict division between his acting life and his private life ('I'm having new track rods fitted on my car,' he once said. 'I don't want to know anything about the man who's doing it. Why should he want to know about me?').

The dark-haired, hamster-cheeked and boyish-looking Bewes, in contrast, was quite a loud, garrulous and very gregarious figure, already notorious in theatrical circles for twisting small bits and pieces of truth into toweringly tall tales, who remained indefatigably 'actorly' even when he was not acting.

One of the sharpest contrasts between them concerned their respective attitudes towards the personal information that they shared. Bolam was a bona fide confidant, a person with whom one could relax and exchange any intimate news safe in the knowledge that it would go no further. Bewes, on the other hand, seemed to have no confidentiality filter in his head; whatever passed through his ears, so long as it seemed sufficiently interesting, would, sooner or later, get revised and repackaged as one more entertaining anecdote to blast from the public address system that often served as his mouth. That was quite an unsettling thought for many of his colleagues, but, for a colleague as private as Bolam, it was positively nightmarish.

An illuminating insight into the difference between the two men can be found in their respective reactions to having been involved with certain iconic music stars from that era. One man brushed the memory aside like a random piece of junk mail, the other polished it up until it shone like a patent leather dance shoe.

Bolam, while he was working on The Likely Lads, shared a flat in Barnes, South West London, with a diminutive young up-and-coming singer named Mark Feld, who later (according to many accounts) 'adapted' his flat mate's surname to re-emerge as Marc Bolan. It would, for many actors, have served as a sound source for countless anecdotes, each successive one slightly more embellished for full and fresh chat show effect, but James Bolam, as usual, never discussed the matter in public.

Bewes, on the other hand, somehow managed to take (what may or may not have been) a fleeting meeting in a music studio with Jimi Hendrix, during which the guitarist (may or may not have) played a few notes on a song Bewes's friend was recording, and - ever the anecdotal upgrader - turned it into the strange claim that he had persuaded the guitarist to play on the theme tune of The Likely Lads. Even though Hendrix was not in Britain when composer Ronnie Hazlehurst recorded the music, and there were no electric guitars discernible on the track, and Hendrix was dead long before the sequel's much more memorable theme tune was written, Bewes never tired of telling the tale, having somehow seemed to have convinced himself that it was all very vivid and true.

For all of their differences, however, the two men worked together remarkably well in those early days. They loved the characters and the scripts and all of the wonderfully and painfully believable situations in which they were put - and because of that, they were bright enough to know that they needed each other, and needed to help each other, and needed to inspire each other, and so they always did just that.

They sat down together on the set, and they looked at each other and they listened to each other; they became, as performers, what they needed to be, as a partnership, to seem real. Whenever the camera came in close they sparked each other off like fireworks.

The effect stretched over, for a while, into their off-screen lives. They even convinced each other, and themselves, that they were friends.

The contact went beyond the confines of the studio. Bewes had a far greater appetite for London's night life than Bolam ever did, but they still socialised occasionally with their respective partners after the studio recordings were over. It was a simple, solid, good-natured professional relationship, enhanced by the fact that both ambitious actors could see that, on the screen, they seemed to possess real chemistry as a pair.

Gradually, however, over the course of three series in two years, tensions did begin to arise, mainly on Bolam's side - partly because, unlike his co-star, he was uneasy about being associated for too long with one high profile role and genre, and partly because Bewes's often over-bearing nature was starting to niggle. When the final series ended, therefore, it was only Bewes who was left with strong regrets, while Bolam simply moved on with relish to his next acting adventure.

It took a combination of factors to bring the two actors, and the BBC, back together again seven years later for a sequel. First, the continuing public affection for the show and its characters created the context for a viable revival. Second, the co-writers, Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais, developed a nagging feeling that there was far more left for them to explore. Third, a key demographic for the BBC (in those days) was made up of viewers who were just reaching the point when, as they edged into middle age, the wistful lines, 'Oh what happened to you, whatever happened to me, what became of the people we used to be?' seemed guaranteed to strike a chord.

It was immediately clear, however, that the prolonged absence, far from making the co-stars' hearts grow fonder, had only actually hardened the habits that had divided them long before. The initial negotiations, as a consequence, proved complicated - on one side more than the other.

Bolam, during the seven-year hiatus, had immersed himself in a wide variety of roles on the stage, radio, television and movies, doggedly eschewing any reference to his celebrated sitcom as he concentrated on the here and now. When fans on the street would shout out, 'Where's Bob, then, Terry?' a grim-faced Bolam would only mutter by way of a reply, 'He's dead'.

Bewes, on the other hand, had never really let go of the show in either his head or his heart, and continued to embrace the memory of it whenever he was interviewed. Although he had since had a spell as the sidekick ('Mr Rodney') to the television puppet Basil Brush, as well as a starring role in his own popular co-written and co-produced (he also co-wrote and sang the theme tune) ITV sitcom Dear Mother.... ....Love Albert, there remained a certain wistfulness in his comments about the show that had made his name.

In addition to these differing attitudes towards the old sitcom, however, were differing attitudes towards each other. Bewes, when asked about the sequel, was delighted at the prospect of working again with James Bolam. Bolam, on the other hand, reacted to the first mention of the revival by shaking his head and saying, 'Not with Rodney Bewes, no'.

As actors, the distance between the two men had grown even wider and more obvious over time, with Bolam the more protean in his approach, looking to lose himself in a character, and Bewes the more personality-based, preferring to find himself in each figure. There was nothing wrong in either style, and nothing wrong with how well each of them executed it, but it would do nothing to ameliorate their working relationship when the show eventually resumed.

Now in their late thirties, they had changed, too, as people - not in surprising ways, but rather by growing more settled within their own skins, with the callow tastes and tics of their younger years now shaped, refined and entrenched as an intrinsic part of their personalities.

Bolam was, if anything, even more protective of his privacy than before - a decent, very serious, reliable member of any cast or company, liked and admired by most of his fellow performers - who simply did his work to the peak of his powers and then expected to be left alone to disappear off to his home.

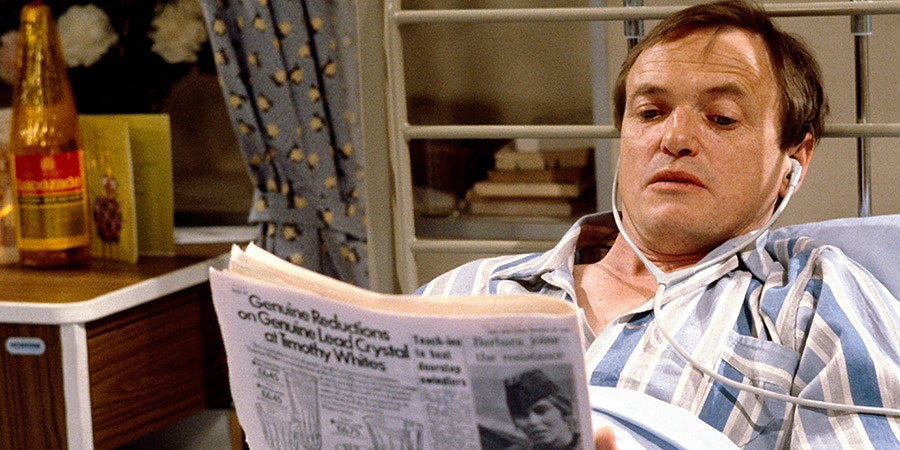

Bewes, on the contrary, was by this time a fully-fledged 'show business' figure proudly showing off all the regalia of modern fame - living in a glamorous London apartment with a couple of Bentleys and a Porsche parked outside; a regular kipper-tied presence at The Garrick and Chelsea Arts Club; an eager participant as 'himself' in television commercials; a frequent interviewee on the chat show circuit; a tireless raconteur; a chronic name-dropper keen to recount his night club encounters with the likes of Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger; and, after a glass or two of red wine, a noisily enthusiastic reciter of old music hall monologues, always delighted to be heard and recognised by passing members of the public.

He was always a much more divisive character than Bolam within the industry. He was considered great company by those of his fellow actors who shared his distinctive sense of fun. Others, however, bristled at the mere mention of his name, calling him 'The Beast' behind his back, and regarded him as a maddeningly unreliable actor and an egocentric bore. 'He doesn't do it maliciously,' Kenneth Williams once remarked of Bewes's excesses, 'cos he's not ill-natured, he is unthinking: that's the problem'.

None of these differences, however, seemed to mean enough - really enough - for the reunion not to happen. Both actors simply loved playing their respective characters, and were sufficiently inspired by the exceptional quality of the new scripts to sign up for the sequel.

Bewes thus breezed back into the production seemingly oblivious to any anxieties within the company. Always more used to being the observed than being the observer, he was never the most sensitive of people, often blissfully blind to those signs, such as rolling eyes and heavy-lidded looks and deep sighs, that signalled the fact that his name-dropping monologues and over-familiar routines were wearing thin; as far as he was concerned, he was simply being welcomed back as the life and soul of the team.

Bolam, on the other hand, just wanted to go in, do his work and go away again, hopefully without enduring as much of the irritation that had irked him the previous time around. He returned, therefore, with a blank-faced wariness that suggested the kind of problems that were set to come.

Sure enough, just as the magic returned more or less immediately on the screen, so too did all the tensions revive behind the scenes. There was no specific incident, no particular problem, no one great explosive moment - just an ever-present and palpable sense of discomfort between the two stars, like a black cloud overhead that was hovering there threatening to break.

Brigit Forsyth, who played Bob's long-suffering fiancée Thelma, would recall the awkward atmosphere in rehearsals and on the set: 'It wasn't great, I was piggy in the middle. But because it was a new thing for me, filming in front of an audience, I didn't notice so much. Looking back on it I think, "Ah ...".'

When, however, she spoke sometime later to the show's two writers, Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais, for their entertainingly candid joint-memoir, More Than Likely, she was more open about how Bewes had exasperated her - along with Bolam - so much that she had often wanted to strangle him: 'It wasn't the thought of going to prison that stopped me,' she said, 'it was simply that I didn't have the strength to finish him off.'

James Bolam coped largely by biting his lip and concentrating on the bigger picture (he would even be overheard saying 'Well done, Rod' when he felt that his co-star had produced a particularly good performance), and also by blocking Bewes out whenever he threatened to distract him with his antics. This passivity worked well up to a point, but it also had the unintended consequence of handing his colleague the initiative to take control of their shared narrative, and thus cause further conflict between them.

Bolam, for example, was more than happy to leave all of the publicity chores that went with such a high-profile show to his co-star, and so Bewes, through his typically ebullient interviews, was effectively given licence to spin the story that all was sweetness and light behind the scenes of this much-loved sitcom, and that he and Bolam remained the very best of friends. That, in turn, would crank up the simmering on-set resentment another notch.

There were even one or two rare instances during the run when Bolam, confiding privately to old allies, would open up and grumble about the strain of the relationship. When, for example, he took part in a voiceover session alongside another actor, Warren Clarke, who had himself collaborated uneasily with Bewes in the past, he was asked what it was like to be working again with 'The Beast'. Bolam merely rolled his eyes at Clarke and said glumly, 'Still the same'. For most of the time, however, he managed if not to grin then at least to bear it.

The fall-out from the infamous phone call in 1977, therefore, was no sudden rupture in an otherwise warm, stable and close relationship. It was, at least for Bolam, merely the last in a long line of irritations caused by his co-star, and a convenient excuse to cut all ties with him for good.

For many years after, Bewes tried rather desperately to maintain the illusion that he was still in touch with Bolam, telling journalists who inquired that they had only recently had dinner together, enjoyed 'a swift half' or met up at the races - 'It was easier that way,' he later confessed - but, after Bolam declined to appear as a guest in his edition of This Is Your Life in 1980, and then ignored a number of other attempts at a rapprochement, Bewes finally began to address the issue in public - first in his 2005 autobiography, A Likely Story, and then in countless interviews over the final twelve years of his life.

It will remain a matter for conjecture how much he really believed, or managed to convince himself, that he was now mourning the loss of a genuine friendship, but certain elements in the narrative that he would recite always sounded somewhat contrived. He made a number of conflicting and confusing claims, for instance, that Bolam, riding high in a succession of other series while his erstwhile co-star was now struggling to revive his flagging career, had selfishly refused to sanction repeats of The Likely Lads on network British television.

In 2007, a mere two years after he had claimed that he was 'happy they keep on showing the old episodes' ('let's face it,' he added, 'you get the repeat cheques, and the bank manager smiles'), Bewes, in a bizarre volte-face ignored by the media, told an interviewer that Bolam had 'vetoed' all repeats of the shows 'for 18 years' on the grounds that it would have been 'a retrospective step' in his career. He then, even more confusingly, conceded that some episodes had since been shown, but then added acidly, 'I'd love to have asked Jimmy, "Did you send the repeat cheque back because of your principles?"'

Bewes returned to the topic in 2010, when (electing to ignore the fact that, even in his relatively reduced circumstances, he still owned a large house in Putney and a substantial holiday cottage in Cornwall) he accused his former co-star of condemning himself and his fellow cast members to poverty: 'Jimmy Bolam's killed it, which is such a pity,' he said of the two related sitcoms. 'I'm very poor so I have to tour one-man shows because Jimmy has buried The Likely Lads. You have to sign a waiver for them to repeat it and he stopped it while he did New Tricks. Well, New Tricks has been on so long, and is so repeated, that he must be very wealthy; me, I've just got an overdraft and a mortgage.' Bewes added: 'He should let it be repeated on BBC Two or BBC One; to stop other people earning money is cruel.'

The reality, however, was that, since Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads? finished its run in 1974, episodes from both versions of the sitcom had been repeated on BBC One or Two in 1975, 1977, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1985, 1986, 1989, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2004, plus 2013 and 2015, in addition to countless re-runs on the satellite channels, as well as numerous repeats of the BBC radio adaptations, and have remained an option in terms of subsequent mainstream repeats.

Many in the media, failing to check such facts, merely sensed a good saga to sell, and proceeded to build up the myth in the public realm of some kind of callous conspiracy, stretching it even further to suggest that Bolam had been blocking most or all repeats since the late 1970s. Bolam himself, meanwhile, as stubbornly private as ever, doggedly maintained a dignified silence.

No solid evidence ever did emerge to confirm the allegations that he had personally attempted, or succeeded, to block any repeats, and, as the records show, the programmes were indeed screened many times during some of the periods when Bewes insisted that they were not. Although it is true that the BBC did not broadcast episodes during the years when Bolam was appearing regularly in New Tricks (2005-11), there is no available archival material to suggest that Bolam himself was involved in this decision, and the actor, when he finally consented to discuss the subject following Bewes's death, strongly protested his innocence: 'How could I do that? I can't stop repeats. A, I get paid for them, which is very nice, and B, there's no way I could do that even if I'd wanted to.'

Bewes, however, never stopped airing the accusations about his old estranged co-star, sounding increasingly embittered as, while Bolam continued to appear on television on a fairly regular basis, he was now reduced to touring increasingly small theatres with his one-man show - a critically praised adaptation of Jerome K Jerome's Three Men In A Boat - which necessitated him, he claimed, driving around Britain in an eleven-year-old Vauxhall Nova with a coat hanger for an aerial, lugging a 24ft boat from venue to venue, and serving as his own road manager, producer, director and backstage crew. At the end of each performance, he would invite the audience on stage, or have a drink with them at the bar, where, inevitably, the same old story, among many others, was re-told.

Even in one of his last interviews in 2015, shortly after the death of his wife, Rodney Bewes was still raking over the coals of the old relationship with James Bolam, seemingly unable to cope with the other man's chilly indifference. Oscillating as usual between rage and regret, he began, with a startling lack of self-awareness, by angrily accusing Bolam of having an 'ego' for thinking that their sitcom was 'beneath him', before slipping into self-pity: 'I would love to be friends with him, but he doesn't want to be friends with me'.

'I can't be like Jimmy. I can't be that angry,' he added sadly. 'We're different animals.' It was actually the most truthful and insightful thing he had ever said about the two of them - they were just 'different animals' - and the great sadness was that it had taken more than forty years for him, so close to the end of his life, to finally admit it.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more