The comic that time forgot - The lives and deaths of Stainless Stephen

A fair few senior comedians have been made to feel terribly old and out of fashion whenever a member of the public comes up and asks them, 'Didn't you used to be...?'. None, however, have been made to feel quite as badly out of date as the former radio star Stainless Stephen once was. He picked up the paper one day and discovered that he was dead.

The claim, in truth, did not come as a total surprise to him. He had, after all, been out of the public eye for quite a while.

At the age of seventy-three, however, he still felt that he was in with a fighting chance of reaching seventy-four. He was disinclined, therefore, to take such sombre news lying down.

Born Arthur Clifford Baynes in Sheffield on 30 November 1892, he had once been one of the busiest, best-loved and cleverest comedians in the country. Adopting his stage name from the invention associated with the steel-making city of his birth, he was an English teacher-turned-comedian (and the son of a linotype operator) whose highly distinctive style was inspired by his genuine fascination with the nuts and bolts of language.

More specifically, he was particularly intrigued by the art and action of punctuation, the unspoken stage directions of speech, and saw, and heard, the comic potential to be had from turning the signs into sounds. This curiosity crystalised into a comic routine while he was working as an instructor at the Northern School of Signalling at Tynemouth during the First World War.

As he was obliged to highlight what was normally hidden as he taught the mechanics of communication, the way that this made the normal sound strange ('Message for Lieutenant oblique stroke comma Colonel...') struck him as a special source, in another context, of great potential amusement. 'Audible punctuation', therefore, became his main way of making others laugh.

He started by telling old and conventional jokes whilst articulating every comma, colon and quotation mark, so that the humour became as much to do with the form as with the content (e.g.: 'At my sister's boarding house all the windows have stained glass, comma, stained with the soup the visitors throw at them, exclamation mark'). Then, as he grew in confidence, he did the same thing with gags and stories and rambling reflections all of his own:

Somebody once said, inverted commas, comedians are born not made, full stop. Well, slight pause to heighten dramatic effect, let me tell my dense public innuendo that I was born of honest but disappointed parents in anno domini eighteen ninety something, full stop. Owing to my female fan following, the final two digits must be left to the imagination, end of paragraph and fresh line.

No one had heard anything quite like it. It was laughing at language; it was satire about structure. It would soon turn him into a star.

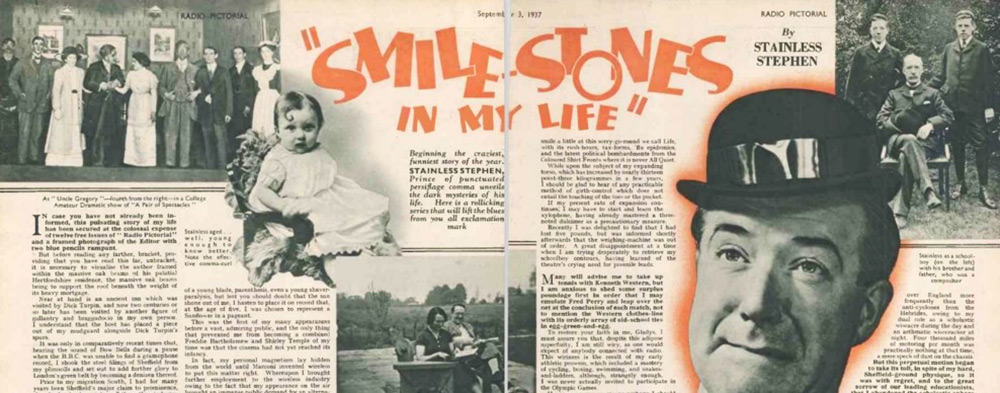

One of the first British comedians to appear regularly on radio, he made his debut on the BBC (or as he would put it, 'the B dot B point C ditto') at the start of 1924 and within a few months had 'spread like marmalade' to become a regular on various entertainment shows (even though he continued to teach full-time as an assistant master at his local Crookes Endowed School). He was known, initially, by his real name of Arthur Clifford Baynes, and played several other speech-specific characters in addition to Stainless Stephen, including Sibilant Cyril, Atmos P. Herics and Oscillating Oscar.

Eventually, the exceptional popularity of the syntactical comedy of Stainless Stephen saw the other figures fade away (or, more accurately, absorbed, to some extent, into the surviving character), and the creator became synonymous with his key creation. He persuaded the Sheffield steelmaking firm of Firth-Vickers to make him a special stainless steel shirt-front; he added a stainless steel band to his under-sized bowler hat, and further embellished the look with luminous waistcoat buttons and even a revolving bow-tie; and he mixed-in some artfully surreal thoughts and smart puns with all the stops and starts of his patter.

Then there was the sound of him. It was rather like Robb Wilton through a megaphone; a harder and flatter Yorkshire counterpoint to the other's softer and richer Lancastrian, with a stronger and sharper sense of exasperation, a less hesitant show of fussiness, but with similar northern rhythms and emphases, and the same sort of dry self-irony. He worked on it, settled into it, and went forward with it.

The profile of Stainless Stephen was thus sharpened. He was now ready to impose the persona upon the country's culture.

The occasional stage appearances increased and the regular radio broadcasts continued ('This is Stainless aimless brainless Stephen, semi-colon, broadcasting semi-conscious at the microphone, semi-frantic'), becoming increasingly ambitious and elaborate in the way that they kept folding the form within the content. Realising that, as the duration lengthened, the amount of audible punctuation needed to be selective to keep the ostensible theme comprehensible, he played on and in words as well as between them, dancing around the three dimensions with remarkable dexterity, such as in this review of the year:

What a wonderful year 1930 was, semi-colon, said Stainless Stephen, semi-conscious. Thousands of new motorists took to the roads, comma, and as a result millions of pedestrians took to the fields. Some cars were fitted on the dashboard with a red light that flickered in and out the day before the next instalment was due. Stand at ease and straight on.

FARMERS, capital letters, had a poor year. Even the BBC had to pronounce 'glaass' as 'glass,' the a being so short (subtile, brackets). One agriculturalist even taught his cows to Charleston, semi-frantic, so that they could churn their own milk, semi-curdled, while another crossed his bees with glowworms to allow them working the night shift...

Fresh paragraph.

1930 has seen some new inventions. The most important is a wheelbarrow fitted with handles at both ends so that two men can do the work of one. A tobacco manufacturer made his cigars half an inch shorter, because nobody smokes the last half-inch anyway, and one Scotsman was tattooed so that he could travel as printed matter...

Compared to the standard stand-ups who dominated the radio in those days, Stainless Stephen sounded refreshingly different, imaginative and engaging for listeners eager to hear material and performances that encouraged a little more care, thought and attention in their reception. One had to listen not only to what he said but also to how he was saying it, and how it was meant, in order to appreciate the full effect.

The novelty drew people in, but then the quality of his material, and the skill of his performances, kept them coming back, making him, as a new decade began, one of the most in-demand entertainers around ('The wireless', he said, joking about his rapid rise, 'enabled a comedian to make ten years' progress without bothering about nine of them'). In 1932, for example, he was voted the most popular radio artist in a Daily Herald newspaper poll, released a record of one of his routines, featured in a BBC series called Vaudeville, made his film debut (in Radio Parade, which was released the following January) and toured the country's variety theatres with his solo act. By the end of 1934 he had gone well past the two-and-a-half century mark in terms of radio appearances.

Realising that he would have to make major changes if he was going to deal with the mounting demands on his time and energy, he finally, rather reluctantly, gave up his teaching job in October 1935 (the decision prompted the headline: 'Comedian, yes, semi-colon; teacher, no, full stop') and moved to London to concentrate on being a full-time entertainer. Now aged forty-two, he wanted, belatedly, to test his full comic potential.

Singular in every sense, he had no need for other writers ('I read a lot of heavy stuff and take an interest in people,' he explained. 'I have never had a scriptwriter. It all comes,' he said, tapping his head, 'out of here'), he was by now a confidently commanding presence on the stage, and as a radio performer his delivery was so powerful that even the BBC's notoriously dour Director-General, Sir John Reith, had pronounced himself impressed with his professionalism. Celebrating the start of his full-time show business career with a radio special he called Tittle Hyphen Tattle, he was ready to embrace all of the opportunities that were now arriving.

There would be more radio work, more tours of the halls, regular summer seasons and pantomimes, and a number of performances abroad (in France, for example, he was celebrated as 'Monsieur Inoxydable'). He was even mentioned in the House of Commons, during July 1936, as an example of what the rather aloof Postmaster General George Tryon should listen to as a means of getting more in touch with the mood of the nation ('He must humanise himself,' said another MP. 'I would suggest that he listens in from eight till nine on Saturdays').

The industry of Stainless Stephen, during this period, was immense. 'There's only one way', he would say of his 'incessant' attitude. 'You've got to treat it as a business. There's no glamour, only work'.

One of the things that particularly impressed his audiences was the meticulous research he put in as he prepared for each performance. Whenever he toured, he would spend his free time in the local libraries, scouring the newspapers, guides and history books for information relating to both the past and the present about each town, and then he would rapidly develop some material that was rooted in the place he was playing.

When he appeared in Peterborough, for example, he surprised many there by launching into comic routines that engaged with a wide range of traditional and up-to-the-minute local events, individuals and themes. 'His topical humour was brilliant', wrote one reviewer. 'It seemed as if he had learned all there was to be known about Peterborough, and proceeded to turn his information into something inimitably funny'.

It was much the same in Skegness, where he teased about current traffic congestions and made fun of several councillors; and in Bristol, where he even mentioned a recently retired train station ticket collector; and also in Hastings, the day after a new mayor had been elected; and the same in Coventry, where he even made fun of an altercation in the marketplace that had happened earlier that afternoon; and the same in Sunderland, where a critic wrote that 'his patter is so full of local allusions so witty and so accurate that Stainless might be taken for a native'; and on and on it went. He was known, for his radio broadcasts as well as theatre appearances, often to still be adding new and pertinent tiny details to his material as he was about to set out to the microphone.

It was that kind of professionalism, and that kind of care, that was making him one of the most admired comic performers around. Audiences knew that they were getting a well-worn act with most comedians of the time. They also knew that, with Stainless Stephen, they were getting something mostly new, and specially tailored for their tastes, every time he set foot on the stage.

It helped cement his status as a star. He was now earning enough money to be able to afford to own a country home at Grange-over-Sands and a town house at Widnes, as well as a rented apartment in London at Pine Grove End and a couple of vintage cars, in addition to being a shareholder in a chain of hotels. He had performed before royalty, and prime political figures, broken multiple box office records up and down the country, and had even had a racehorse named after him in his honour.

Throughout the second-half of the Thirties he was, without any doubt, one of the most successful comedians in the country.

Fiercely patriotic, and still haunted by his harrowing memories as a survivor of the battle of the Somme, he toured Europe and the Far East during the Second World War to entertain the troops (where his bravery - he didn't just perform at organised events but also in foxholes, travelling by jeep from unit to unit to wherever he might be needed - earned him the soubriquet of 'The Front Line Comedian'), whilst continuing to broadcast regularly on the radio. He also endeared himself to the public back home by visiting factories, hospitals and schools to lift morale, championed numerous government campaigns and worked tirelessly to raise funds for the poor, the elderly and the bereaved.

A good judge of when the mood was suited to escapism and when something more topical was required, he modulated the tone of his broadcasts well, choosing his moments to be more pointed and political in his humour. In a monologue during March 1941, for example, he made some affectionate references to the adventures of the Home Guard, alluded to the need for American involvement, stressed how strong the national spirit remained, and ended by saying: 'And so, countrymen, semi-colon, all shoulders to the wheel, semi-quaver, we'll carry on till we get the Axis semi-circle, and Hitler asks us for a full stop!'.

His continuing contributions to the war effort were actually so constant, and so noticeable, and frequently courageous, that it came as something of a surprise when, unlike a number of other, similarly public-spirited entertainers, he was overlooked for an official honour. His commitment, nonetheless, remained sincere and intense.

Once the war was finally over, however, he seemed to be drained of ambition as well as energy. He had hardly had any proper rest for several years, and his health had suffered during his arduous wartime tours, with him succumbing to dengue fever for several weeks in what was then known as Ceylon. He was hospitalised again late in 1945, back home in England, undergoing what was described as a 'serious operation' at St Lukes in Bradford.

There was the honour of an appearance at the Royal Variety Performance in 1946 at the London Palladium, which he enjoyed immensely, but, after that, the arc of his remarkable career began its slow descent. He was still very popular with the public, and well-regarded by the critics, but he was beginning to find all the touring more of a chore.

There was still plenty of work for him in radio, but he was growing wary of repeating himself (as well as frustrated by the BBC's increasingly cautious attitude to topical humour, which was hindering his 'stop press in jest' style of script). Television never really interested him (although he had appeared on it as far back as 1937), and he resisted several offers to explore his potential in that medium. He had been rather good in his solitary cinema excursion, but the industry had since moved on, and his own gifts no longer seemed suited. There were no regrets on his part; he felt that where he had come to rest best reflected his strengths.

'It seems', he reflected, 'that I have now tried everything there is to try in the sphere of entertainment, with the exception of being shot from a cannon, or placing my head in a lion's mouth'.

By 1952, on the verge of sixty, he decided that he had had enough, and announced his retirement from show business. 'You can't go on for ever,' he said. 'I think I'm just a bit past it'. Satisfied with what he had achieved on the stage and radio, he resolved to start plotting an entirely new way to live his life.

During the war, he had preferred, when performing at provincial theatres, to stay at the nearest farm, rather than lodge in a local hotel, and spend his free time working on the land (High Cross Farm in Wolvey, Warwickshire, becoming a particular favourite). He had actually enjoyed the experience so much, and grown so curious as to the business of agriculture, that now, as he looked for a third career, he found himself drawn to the idea of finding a farm of his own.

In 1954, after a couple of years of searching, he eventually decided to settle on a place in Kent called Chested Farm in the village of Chiddingstone, on land (all 125 acres of it) that nestled within the well-wooded countryside between Tonbridge and Sevenoaks. Declaring himself a 'gentleman farmer' - 'All I raise is my hat' - he was actually very serious about his new career, and committed to making it work.

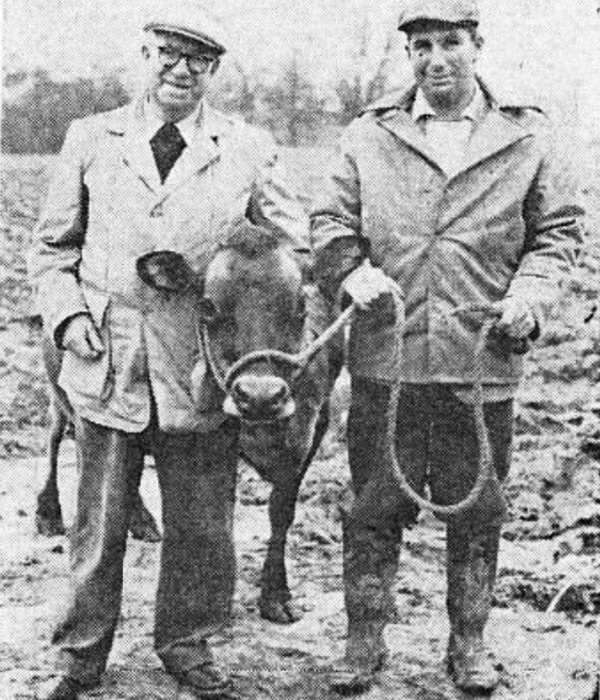

Always rational and rigorous in whatever he did, he now devoted an intense period of time to researching the many intricacies of milk production, and it was not long before he was making a success of his new venture. Within a few years, his pedigree Jersey herd had risen up to second in Kent with an average yield of more than a thousand gallons from twenty-three cows.

Supported by his wife Jean and their son Ian, he was thoroughly content in this new environment. He did make the odd appearance at London charitable events, where he could meet up with a few of his old friends from his radio days, and accepted an occasional invitation to address various Chambers of Trade as an after-dinner speaker, but most of his time was now spent out and about on his tractor or labouring away on his land.

He was, indeed, so invested in the civic culture of the area that he also served, for a spell (1959-62), on Sevenoaks Rural District Council. It was said that, although some of his contributions could end up sounding more like stand-up routines, he took his responsibilities seriously and volunteered plenty of ideas for practical solutions to ongoing problems (including the pressing need for a public convenience for the frustrated people of Penshurst and Leigh).

A prize-winning racing cyclist in his youth, he had taken to his bike again now as he looked to maintain his fitness into his seventies, pedalling through the country roads at a pace that some found surprising. He was a familiar figure locally, but only, to most people, as 'old Arthur', the man who happened to live on the nearby farm.

Then, however, came the confusion that would, for a while at least, thrust him, and Stainless Stephen, back into the public eye. It happened in the summer of 1966, while the national spirit was still shimmering with the afterglow from the excitement of England winning of the World Cup, and the tabloids were in quite a whimsical frame of mind.

The comedian Stainless Stephen, now farmer Arthur Clifford Baynes - having passed the semi-colon stage but still some distance from the full stop - had been retired from show business, but not from life, for more than a decade when, one morning, he was perusing his newspaper over breakfast when he came across the report declaring that he was not only dead, but also had been dead for a number of years. It was in a letters column in the Daily Mirror, published on 10 August, called 'Old Codgers'.

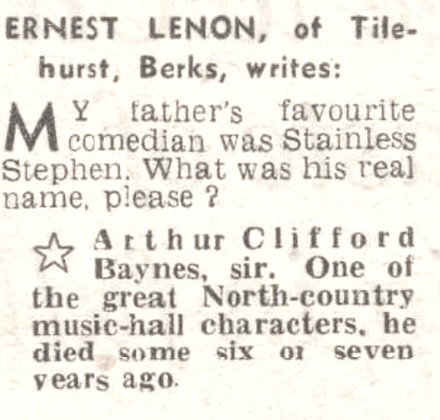

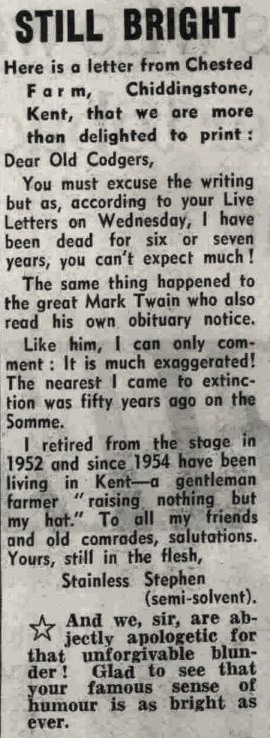

A young reader named Ernest Lenon, of Tilehurst in Berks, had written in with a question: 'My father's favourite comedian was Stainless Stephen. What was his real name, please?' The Mirror answered perfectly correctly as far as his appellation was concerned, but then added: 'One of the great north country music-hall characters, he died some six or seven years ago'.

This was certainly news to the man himself, who was quick to register his scepticism. Two days later, the 'abjectly apologetic' newspaper printed his response: 'Dear Old Codgers, You must excuse the writing, but as, according to your Live Letters on Wednesday, I have been dead for six or seven years, you can't expect much!' Echoing Mark Twain's famous line about his expiration being much exaggerated, he sent salutations to all his old friends and comrades, signing off: 'Yours, still in the flesh, Stainless Stephen (semi-solvent)'.

'We checked all through our file of newspaper cuttings,' someone at the Mirror later explained, 'and we couldn't find anything about him for the last few years. So we phoned an entertainments magazine, and they told us he was dead. Well, you can't really blame the magazine. They probably had a relief duty or something, and after all you can't come down too hard on people who are trying to help you. It was an awful mistake to make, though'.

The coverage of the erroneous obituary sparked a new wave of interest in the old, but most definitely still alive, veteran radio star ('I've got to reply to about a hundred letters now', he said, pretending to grumble). The family farm was suddenly invaded by a succession of newspaper and radio teams, countless photographers, and several old fans who wanted to see him in the flesh. There was even a television appearance, in November 1969, on David Frost's show Frost On Saturday, in which he so enjoyed himself, after a somewhat nervous start, that he practically took over the show for several minutes while ignoring attempts off-camera to wind him up.

'When I retired', he would reflect when one journalist sought him out to discover what had happened since his disappearance from public life, 'I decided it was best to make a clean break and so I seldom make any public appearances now'.

He appeared quite content, in spite of his sudden 'rediscovery', to be seen as fully out of fashion, playing mischievously on the combined stereotypes of the lugubrious Yorkshireman and the cranky farmer to accentuate the effect. Listing 'the Labour Party, long-haired pop singers and nuclear disarmers' among his current pet peeves, he preferred to guide any visitors through the granular details of his many learned tomes on the two world wars ('That book there', he would say excitedly, pointing at a shelf, 'will tell you more of the battle of Kohima than any other book I know'), or rage for a while about the local one-way traffic schemes ('There's getting to be so many islands in Tonbridge it'll soon look like the Outer Hebrides').

Once the interest died down again, he took his retirement even more seriously than before. With his son now in day-to-day charge of the farm, he spent his final years reading his way through his large library and taking long and healthy walks over his fields.

He died on 13 January 1971 at his home in Chiddingstone, one week after suffering a heart attack. He was seventy-eight.

Although he had not seemed too bothered about his later reputation as a semi-forgotten star, his impact, in fact, would live on. His long success on radio with his short comic monologues paved the way for other quirky speakers to follow, including Gerard Hoffnung, with his charmingly surreal ramblings, and Stanley Unwin, with his crafty gobbledygook.

The legacy of the old comedian would actually stretch far beyond this. His kind of humour was the sort that made people think ('dot-dot-dot'). A new generation of imaginative, intelligent and inquisitive comics had grown up listening to and loving the way that he had with words.

Spike Milligan, for example, had taken some of Stainless Stephen's style of wordplay and imagery as an ingredient for The Goons (whose other members, Peter Sellers and Harry Secombe, had started out on stage doing impressions of his distinctive delivery), and thus contributed to much of the new wave of comic groupings that followed, while Peter Cook, as another youthful fan, showed the influence in the way that he used the structure as well as the sense to build up his comic effects. There would also be plenty of echoes of Stainless Stephen in Ronnie Barker's many routines for The Two Ronnies and elsewhere, that involved him manipulating language and its conventions as a means of eliciting laughter.

Even now, therefore, the reports of the death of Stainless Stephen still remain, in a sense, somewhat exaggerated. You might not remember the name, nor the original material, but, here and there, you and many comics are still tapping into his signature spirit (open brackets, exclamation mark, close brackets).

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more