Stage Fight: When comics fall out in plain sight

The history of British television comedy is littered with tales of the co-stars who couldn't stand each other off-camera. Stuck together in a long-running sitcom, the likes of Rodney Bewes and James Bolam in The Likely Lads, or Jimmy Jewel And Hylda Baker in Nearest And Dearest, could hardly wait to escape each other's company. At least, however, the recording time for each series was relatively short, and the time away from the set relatively long, so there was always a chance to cool off and calm down between those periods when the lips had to be bitten and the friendship had to be faked. In the theatre, however, it's always been different. Trapped together in a lengthy tour, play or panto, it's harder to hide the tension. On the stage, everyone can hear you scream.

While the most tempestuous of TV partnerships have thus largely been able to keep their most egregious explosions away from the eyes and ears of their audience, some of the worst theatre pairings, lacking the discrete assistance of careful editing and corrective re-takes, have struggled to stop their spats from spilling out straight in front of their paying customers. It's often been awkward, occasionally ugly, and on some occasions downright violent.

Double acts, for example, have a notably ignoble tradition of their partners ending up getting pugilistic. The pattern was so prominent that Neil Simon dedicated an entire play to it, The Sunshine Boys, in which the two ageing comics, Al Lewis and Willy Clark, have grown so tired of each other's attitudes that even the odd improvisation, such as one of them suddenly deciding to say 'enter' instead of 'come in' during a tried and tested sketch, is enough to send the other one into a volcanic rage.

Plenty of real-life American comic pairings have succumbed to such a sorry fate. In the late 1930s, for example, the American comics Eddie Cantor and George Jessel were performing a routine together at a theatre in New York. During one evening's appearance, Cantor, feeling bored of going through the motions yet again, suddenly ad-libbed a line that got a big laugh. Jessel, his competitive comic instincts duly triggered, reacted by ad-libbing his own line, which got an even bigger laugh.

Cantor, after trying and failing to come up with another ad-lib, took his shoe off and hit Jessel over the head with it. This sparked the biggest laugh so far.

Jessel, enraged at the injustice of it all, responded by walking down to the footlights and addressing the audience directly. 'Ladies and gentlemen', he said with a scowl, 'this so-called grown-up man, with whom I have the misfortune of working, is so lacking in decorum, breeding and intelligence that, when he was unable to think of a clever retort, had to descend to the lowest form of humour by taking off his shoe and striking me on the head. Only an insensitive oaf would sink so low!'

Having got that out of his system, Jessel sighed, rubbed his head, smoothed down his suit, and walked back to his mark - and then Cantor hit him over the head again. It got the biggest laugh of the night.

Such public meltdowns, between so-called 'friends', would come to seem, in the years that followed, more the norm than the exception amongst Stateside comedic duos. Abbott & Costello, Martin & Lewis, Cheech & Chong - all of them eventually disintegrated as the friendship fell apart, and quite often in full view of the paying public. Abbott & Costello, for example, ended up detesting each other so much that, during some club appearances, the fake fighting grew real and the sound of stinging slapping shook the fans in the front row.

It has never been quite as widespread or as bad on this side of the Atlantic, but, nonetheless, there have been a few depressing incidents over the decades. The brothers Mike and Bernie Winters, for example, became so angry at each other that, during their final year as a double act, they sometimes started fighting as they were walking off the stage.

Then there are the partnerships that, though never quite descending to full-on public punch-ups, certainly deteriorated to the extent that, for some audiences, it felt more like watching a bad marriage than a comedy duo. Think, for example, of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore during the death-throes of their Derek and Clive days, when the drink flowed and the insults hit home, or Rob Newman and David Baddiel sniping at each other as they passed on stage, or Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson on their final tour of Bottom, when sometimes neither could still be bothered to pretend that the old bond was quite as strong.

'Deep down', Bobby Ball would joke to his partner, Tommy Cannon, 'you really hate me, don't yer?' It touched a nerve, that line, among many double acts, and it has been tempting, when watching some of them, to suspect that the sentiment was all-too true.

Such tensions, however, have never been limited to the club or stadium circuit partnerships. Some of the most volatile, and violent, comedic relationships in plays have spilled over from fights in the shadowy backstage area into squabbles in the full glare of the spotlight.

One memorable example involves Noel Coward, when in 1915, at a very early stage in his career, he was touring in a production of the cross-dressing farce Charley's Aunt in the company of his fellow actors Esmé Wynne and Arnold Raynor. The catalyst for this clash was the decision to make Coward room with Wynne rather than Raynor (on the grounds, according to the production manager, that two men sharing a room would give the show a bad name).

Coward and Wynne were, at least initially, very good friends, but were not without their tensions, and, forced into close proximity in a succession of cramped little digs, the niggles started to grow more numerous. Things had become especially bad by the time that they reached Chester, when Coward was caught 'borrowing' Wynne's make-up, and got even worse in Manchester, when Wynne forgot to book their accommodation, and then exploded into outright violence in Wolverhampton, when Wynn finally lost patience with her friend and, after shaking him vigorously by the shoulders, punched him hard straight in the face.

Coward, who was waiting in the wings at the time to make his entrance, was knocked flat on the floor, and had no option other than to get back up on his feet and stagger onto the stage with blood dripping down his cheek, his shirt collar torn and his white tie curled over his left ear. Once he was back in his dressing room, however, he went off to Wynne and announced angrily, 'Now, then - we must have this out!' She promptly punched him once again in the face and knocked him down again.

Infuriated, Coward staggered back up and threw a make-up box at Wynne. She responded by striking him yet again, this time so hard that he hit his head on a wall and slid back down to the ground unconscious.

It was at this point that their co-star Arnold Raynor, upon hearing the commotion, raced into the room and, upon seeing what had happened to Coward, struck Wynne on the head with a hairbrush. She fell down as well, joining Coward flat out on the carpet. A number of fans who had arrived backstage to collect their autographs were thus left staring at their prostrate bodies.

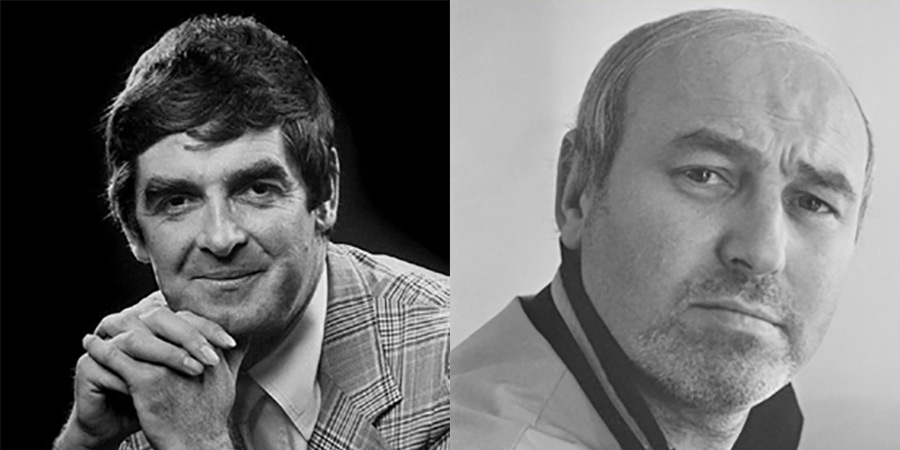

Perhaps the most notable example of these close encounters of the head-hitting kind, at least in the context of British comedy, arose when Bill Maynard was paired with his fellow comic actor Derek Nimmo. It was meant to be a formula for fun; it turned out to be a recipe for resentment, rage and revenge.

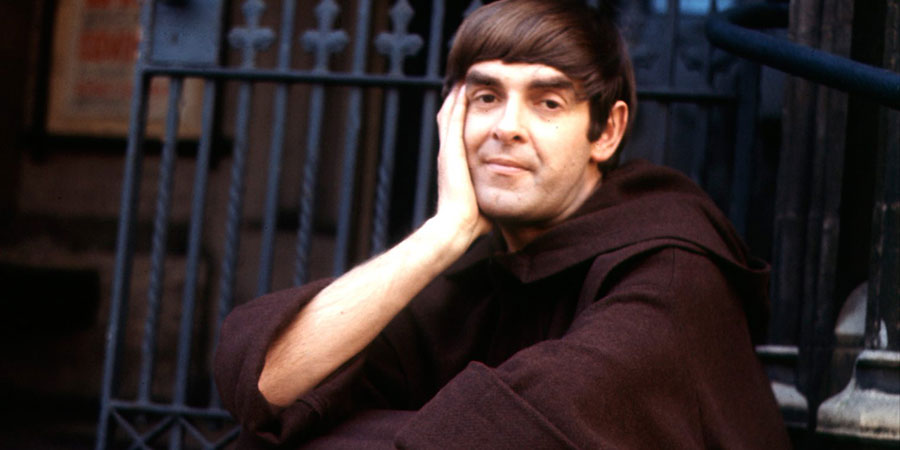

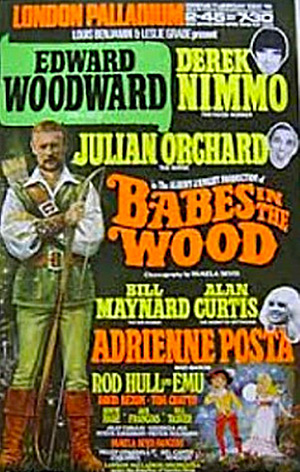

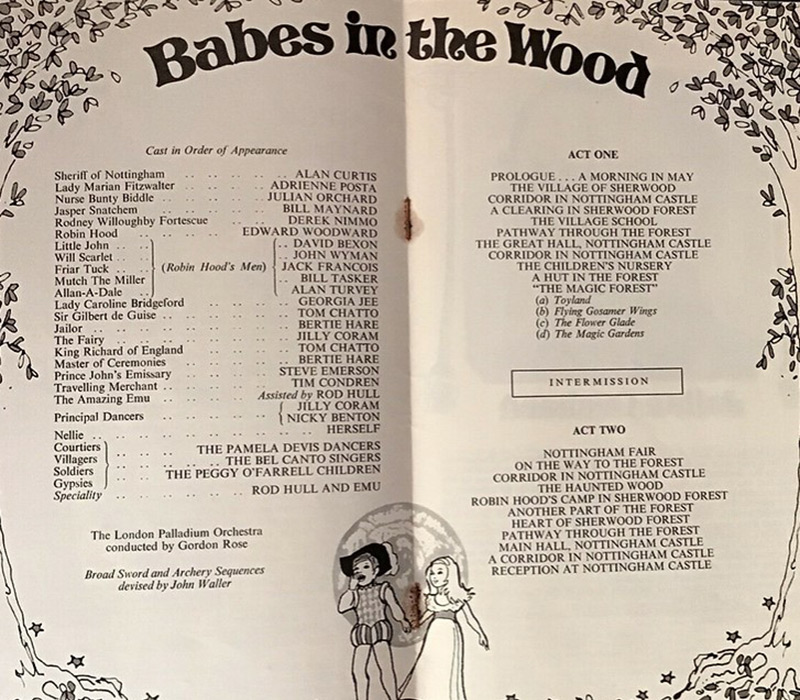

In the summer of 1972, the agent Richard Stone, who at that time represented both actors, was asked by the impresario Leslie Grade to help him cast a prestigious pantomime - Babes in the Wood - for the London Palladium. Edward Woodward (hugely popular at the time after appearing in several series of the TV spy series Callan) was to be the star, with support from the likes of Adrienne Posta, Alan Curtis, Julian Orchard and, of course, Rod Hull and Emu.

The burly Maynard had already been sounded out about playing the tougher of the two comedy robbers, but Grade wanted the increasingly in-demand Nimmo (who was on tour abroad at the time) to play the other one. Stone, however, was uneasy about the suggestion, knowing that there was bad blood between his two clients.

It dated back to the mid-1950s, when Maynard was working mainly as a stand-up comic and Nimmo (who was two years his junior) was first dipping his toe into show business as a stage manager. When, in 1956, they came to work together on a panto - Aladdin at the Empress Theatre in Brixton - the animosity between them was more or less immediate.

Maynard was to appear in the production, and Nimmo was to work on it behind the scenes. This, in the latter's eyes, made them colleagues, but, in the former's eyes, it made them master and slave.

Maynard - by far the more experienced of the two, having already starred in his own TV show (a collaboration with Terry Scott called Great Scott - It's Maynard!), and currently, as he would later confess, 'drunk on my own success' - wasted no time in bullying his younger associate around, sending him on trivial errands, blaming him for any errors on set, mocking him in front of the company and generally making his life a misery. Maynard thought nothing of it when the production came to an end, but Nimmo would never forget it.

By the start of the 1970s, however, the tables had been well and truly turned, and, for Maynard, the old lesson 'be kind to people on the way up, because you'll meet them again on the way down', was, belatedly, about to hit home hard. His status had declined quite dramatically over the course of the previous decade: sliding steadily and seemingly inexorably from star to has-been, he had fallen out of favour with TV producers after clashing with them one too many times, and fallen into huge financial problems with the Inland Revenue after failing to pay attention to his tax, and, after being forced to sell his big house in Fleet to settle in a much smaller one in Sapcote, had for a long time been teetering on the brink of bankruptcy and taking on just about any work that he could find.

Nimmo, in stark contrast, had gone just as rapidly in the opposite direction, having starred in a long-running and award-winning West End hit - Charlie Girl (at the Adelphi from 1965 to 1971, for a run of more than two-thousand performances) - as well as a couple of popular TV sitcoms - All Gas And Gaiters (1967, 1969-71) and Oh Brother! (1968-70) - and had recently been named as the Variety Club of Great Britain's Showbusiness Personality of the Year. He was now in the enviable position of being able to pick and choose his next projects at his leisure.

Intrigued by the idea of a high profile (and very well-paid) West End pantomime, Nimmo asked Richard Stone if Maynard would be prepared, this time around, to behave in a professional manner, treat him as an equal, refrain from any bullying and not attempt to steal any of his laughs on stage. Stone, crossing his fingers behind his back, assured him that this would indeed be the case.

Stone then summoned Maynard to his office, told him with whom he was set to be partnered, and made him swear to treat Nimmo, this time around, with proper respect ('I don't want you to shout at him or take the piss out of him. Most of all, I don't want you to hit him'). The desperate Maynard, affecting the humility of a much-changed man, nodded repeatedly and promised him that all would be sweetness and light ('You know me, governor!').

Stone then sorted out the contracts with Leslie Grade and his team and the preparations went ahead. As to what happened next, there are two main primary sources: although Nimmo (even though he was a prodigious memoirist and anecdotalist) would never discuss any aspect of the incident(s) in public, Stone would provide a candid and very balanced account in his 2000 autobiography You Should Have Been In Last Night, whereas Maynard, while scrupulously avoiding identifying Nimmo by name (he only referred to him, rather patronisingly, as a 'rising new star', or 'the gentleman in question', or 'a clerk', or, blatantly inaccurately, as 'a newcomer to the stage'), would write about the experience, to a fashion, in his 1997 memoir, Stand Up...and Be Counted.

It appears that as soon as rehearsals began at the start of December, all of the old tensions between the two men returned. Maynard, first of all, was rattled by the sight of the playbill, which had Nimmo's name up in large letters as the second lead, while his own name (he would exaggerate) was 'right down there at the bottom, in type so small that if a fly had landed on it my name would have been obliterated'. Remembering his promise to Richard Stone that he would behave, and knowing just how much he needed the money, he gritted his teeth and tried to seem reasonably pleasant to his now far more successful new colleague when they first met up again, but deep inside he was already feeling a strong desire, as he later admitted, 'to hit him'.

Nimmo, meanwhile, being eager to maintain the momentum by making a big impact on his return to the West End, had commissioned a scriptwriter to provide him with several pages of bespoke comic material to smuggle into the production. Maynard, upon discovering this, did not hesitate to point out, as the more experienced pantomime performer, that not only would the additional material cause the show to overrun, but it would also bore all of the children who appreciated visual gags far more than verbal ones.

It was now Nimmo's turn to seethe behind a fake smile as Maynard won over the producer, Bert Knight, and succeeded in getting all of the new written material dropped in favour of some tried-and-tested bits of comic business that Maynard had used in previous pantomimes. That victory, the preening old pro felt, would put the younger man firmly in his place.

Then, however, it was his turn once again to have his feathers rudely ruffled. It began when Nimmo retaliated to the loss of his extra lines by questioning the quality of Maynard's new suggestions, especially a brief routine that started with his 'growing' a fruit tree and ended with him throwing fruit pastilles out to the children in the audience. Everyone liked the idea, he would later say, except Nimmo, who sighed and remarked: 'I think we can find something funnier than that'.

Maynard, who had stubbornly retained all of his pomposity long after losing most of his power, was infuriated by what he regarded as the sheer impudence of a 'young' man who, years before, had merely been 'the clerk who brought me my wages', but who was now daring to criticise his superior stagecraft. The critiques, however, kept on coming, and, after enduring a couple more days of them, they would eventually cause him to snap.

As Maynard - clearly still fuming about the incident so many years later - would recall in his book:

One day, just before opening night, the gentleman in question came up to me and made some suggestions of how I should change my performance. This newcomer, damn it, was giving me notes! I waited until he finished and then coined a new phrase: 'If you give me one more note, I'm going to turn you into a mural'.

He stepped back, hands raised in genuine alarm. 'I don't know what you mean'.

'I'm not surprised', I said. 'What I mean is that if you don't stop giving me notes, I'm going to put you all over that fucking wall...'

A shaken Nimmo retreated for a while after that unexpectedly intimidating exchange, but the power struggle would see-saw onwards long after the production had opened.

Maynard, feeling that he had finally re-established himself as the rightful alpha male of the supporting cast, proceeded, bit by bit each afternoon and evening, to undermine his fellow actor during the performance, using all of his old tricks to dominate the scenes they shared and monopolise most of the laughs.

Nimmo, who by this time had accumulated a fair few tricks of his own, but was currently far more interested in keeping the comedy pacy and on point, became, as a consequence, increasingly exasperated by the way Maynard (after lecturing his colleague on the importance of not over-running) was now quite shamelessly ad-libbing so much that each routine was taking about twice as long to complete - especially as it was always left to Nimmo to find a suitably discreet way to drag Maynard back to the plot.

Both men, separately and privately, were now calling their mutual agent, Richard Stone, protesting about each other. Stone would recall that his advice, repeatedly, to Nimmo was, 'Please do your best to ignore him', while his advice, repeatedly, to Maynard was, 'Please be a good boy - and don't hit him'. That worked for a while, for both of them, but then, quite spectacularly, it didn't.

The escalating animosity finally came to a head, quite literally, during a scene which saw the two robbers attempt to break into a safe. Nimmo and Maynard had been performing this over and over again for quite some time, with Nimmo trying to keep it more or less as it had been rehearsed, and Maynard trying to change it however he felt, on any particular day, it should be changed.

As rehearsed, the slapstick routine was supposed to proceed with Maynard, who was holding a steel wedge, instructing Nimmo, who was clutching a rubber hammer, as to how to help him prise the door of the safe open: 'When I nod my head', he would say, glancing down at the wedge, 'you hit it'. Nimmo's dim-witted character would then nod obediently and hit the head rather than the wedge.

Eventually, however, Nimmo, after having endured yet another evening of his co-star stepping on his lines, stealing most of his laughs and ad-libbing away from the action, suddenly cracked. Enraged at receiving a crafty wink as yet another cue, quite deliberately, was missed, he started hitting Maynard over the head repeatedly, and very hard, with the rubber hammer. Once that started to bore him, he reached over and picked up a wooden handle, and began beating his colleague with that second and rather harder instrument instead.

Most of the children watching, being children, simply lapped-up the violence and cheered more and more as Nimmo continued to batter Maynard. It took the latter's body to collapse into a heap, and be hastily hauled off the stage, for the children to sense that the action was over and start cheering and applauding.

Maynard, in his memoir, would completely ignore this incident, perhaps because, if he had included it, he would also have had to include at least some of the inconvenient details that had precipitated it. Many contemporary observers, however, would later confirm that it most definitely occurred, and Richard Stone, who happened to be in the audience on that occasion in the hope of seeing peace break out between his two tormented clients, went on to describe it in detail in his own book.

The result, backstage, was that the now semi-conscious Maynard was quickly assessed by a local doctor, the show was brought to a premature close, and the dazed actor, after notifying the management that he was suffering from concussion, was driven back to his home in Leicester. That, it seemed, was that.

Nimmo, initially, was triumphant. The battle, backstage and onstage, was finally over, the panto was now being played as planned, and the sense of camaraderie amongst the cast had belatedly been greatly enhanced.

After a few days of having to carry Maynard's less-than-capable understudy through the show, however, Nimmo actually started pining for his old enemy. The show was suffering, he realised, so something had to be done. In a move, therefore, that startled just about everyone else involved, he urged the bosses to hurry up and bring back Bill Maynard.

Maynard, once he had moaned long enough ('It's against doctor's orders, governor...') to finagle himself an under-the-counter cash bonus, did indeed return. It didn't take long, however, before the old toxic cycle resumed turning.

One morning a short time later, two phones started to ring in Richard Stone's office. On one line was Derek Nimmo. On the other was Bill Maynard.

Nimmo told Stone that, in order to 'freshen-up' the panto, he had recently acquired a blank cartridge pistol, with which he had threatened Maynard's character in the duel scene. He had, he said, fired it harmlessly up into the air, but Maynard (in spite of previously introducing plenty of his own props without bothering to warn his co-performer) had reacted to this surprise by storming off the stage and had refused to go back on for the second house.

Maynard, on the other phone, told Stone that, having already been beaten about the head and neck by Nimmo with a rubber hammer, he had feared the worst when his co-star had suddenly produced the pistol and, according to his account, aimed it directly at his nether regions. 'I am NOT', he shouted, 'going to risk having my BALLS blown off by that madman!'

Once the ear-rattlingly indignant-sounding Maynard had made it crystal clear that, unless immediate action was taken, he would not go back on stage for the forthcoming evening performance, Stone arranged for the two actors, along with Bert Knight and Leslie Grade, to join him in an office at the Palladium for an urgent clear-the-air meeting. What followed had an air of farce about it.

First off, Grade and Knight took turns to aim the allegedly offending pistol at each other's groin in order to assess how uncomfortable the experience might have seemed. Both of them came to the conclusion that, had such a pistol indeed been pointed at their respective groins, it would indeed have been alarming, but they did not get very far in establishing if, or if not, said pistol had truly been aimed at Maynard's groin, rather than, as Nimmo had claimed, up in the air.

Maynard, meanwhile, chose to focus on the earlier, more easily corroborated, assault. He started pointing angrily at what the others regarded as an invisible dent in his cranium, claiming that he was almost certainly still suffering from concussion.

Nimmo, concurrently, invested his energies into mounting an eccentric form of defence against Maynard's latest allegations. He thus began hitting a startled Richard Stone on the head with his rubber hammer, demanding that he acknowledge that it was causing him no real pain.

No significant progress had been made by the conclusion of this group discussion. Grade and Knight walked away rather awkwardly, muttering to each other, while Stone went off rubbing his head.

According to Maynard's later (highly selective) version of events, he and Nimmo had their own, much calmer, tête-à-tête soon after that chaotic meeting. It was prompted, Maynard would claim more than somewhat implausibly, by an almost Dickensianly meek Nimmo knocking on his dressing room door one morning and asking to have it explained to him 'what he had been doing wrong'. 'I told him, of course, in no uncertain terms', Maynard wrote, 'and, to give him his due, he marked my advice down as a serious and important lesson in theatrical etiquette'.

According to the far more reliable Richard Stone, on the other hand, both parties simply accepted a stern warning from the management to behave themselves, then bit their lips, and the show went on to the end of its scheduled run without further, noticeable, incident. A fragile truce was, just about, maintained until each was finally able to escape from the other.

Amazingly, Maynard would later make the jaw-dropping claim that, as the passage of time peeled away the memory of the pain this 'spat' had engendered, he and Nimmo actually became 'close friends'. Such an assertion caused many of those who knew both men to splutter with incredulity.

Nimmo, however, not only maintained a dignified silence while his 'close friend' continued to sneer about the 'clerk who used to bring me my wages', but was also magnanimous enough, when he heard that Maynard was struggling through one of his fairly regular economic downturns, to reach out and offer him some quite lucrative work in the overseas theatrical productions he was by now overseeing. 'I'll work for you,' Maynard responded to his 'close friend' rather less than magnanimously, 'but not with you'.

Those two comic actors muddled on, to a fashion, while other fights, in their wake, would follow. It will probably always be one of the latent hazards of the live environment, the emotional sinkhole of the stage, but one can at least learn from looking back at previous public fallings out, and be a little better prepared to defuse any ticking tension bomb before it actually detonates right in front of an audience. Just remember to keep a helmet handy, and beware of colleagues bearing rubber hammers.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more