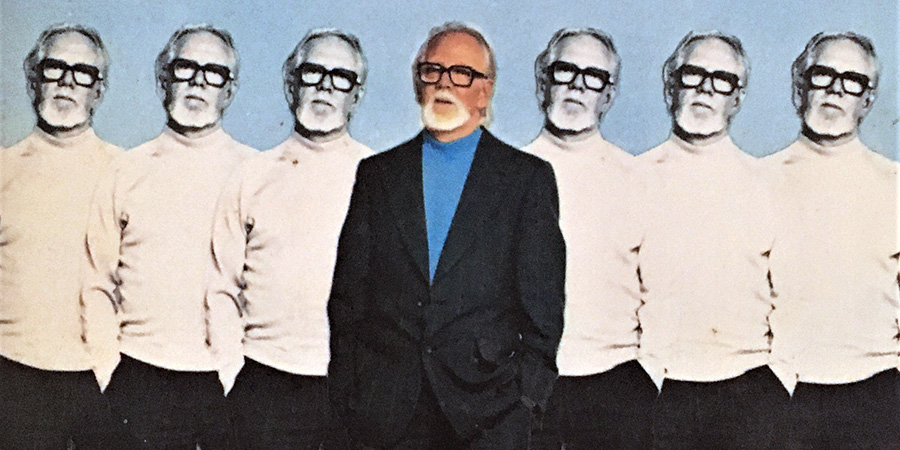

The sinuous comic art of Spike Mullins - Before I begin I'd just like to say...

There's an old saying among writers: 'Where were you when the page was blank?'

Most people who claim they want to write are wrong. What they really want to do is to have written.

They imagine the fun to be had after the fact, while blocking out all the pain and strain of the pre-fact slog - the great and horrible fog of nothingness that sinks down and surrounds you as you contemplate the cold white page. They are often not even right about the fun part - that part, in reality, is usually reserved for the stars rather than the scribblers.

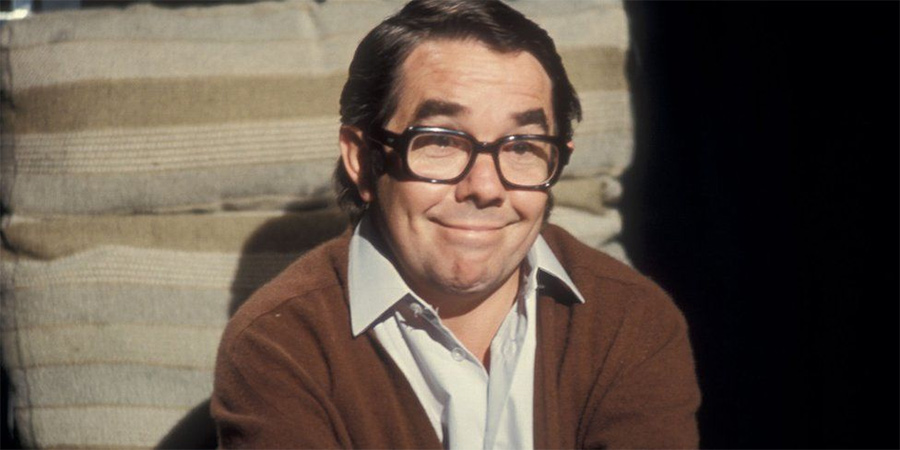

That is what happened, for example, when a small man sat down in a big chair and told all of those tall tales on TV. The scripts were written by a man called Spike Mullins, but Ronnie Corbett got all the credit.

It is a little different these days, but, back in the Sixties and Seventies, comedy shows tended to close with shots of the stars as all the names of the writers scrolled by at a 'blink and you'll miss it' speed. Spike Mullins's was one of the few monikers that some viewers might have noticed, simply because it so often figured in such lists, and also because it stood out like a misprint of 'Spike Milligan,' but while the performers for whom he wrote stayed pin-sharp on the celebrity scene, he, like most of his colleagues, remained a blurred and ephemeral presence.

If, by the way, you are wondering as to why we have taken some time to get to the actual subject of this piece, it is because the subject of this piece was such a master of the art of meandering. 'So let's talk about Spike Mullins,' he might have written. 'But first: here are some other things...'

Spike Mullins was a comic sat nav that was dedicated to detours and diversions. You turned it on to enjoy the journey, never to get to the destination.

He was one of the most productive and influential comic scriptwriters of his generation, but, outside of British entertainment's inner circle, one of the least properly appreciated. This, then, is a celebration of an under-celebrated comic figure; a man who, indirectly, got millions laughing about, and through, indirection.

Born Dennis Jeremiah Mullins on 2nd October 1915 in a room above a sweet shop on Bromley Road in Southend Village in south-east London, he would follow a route to a career in writing that was even more circuitous than any of the stories he went on to structure. The son of parents 'so ill-matched that I sometimes wonder if they got married for a bet,' he was a sickly child who was plagued by 'so many ailments' that he seemed more likely to become 'a laboratory specimen' than assume any of the adult roles about which he dreamed.

The Mullins family lived near a fledgling silent film studio at Southend Hall, so his ambitious mother often touted baby Dennis, along with his older sister, Kathleen, for screen time. 'Apparently whenever there was a part for a small boy that the audience would feel sorry for my mother used to wash me and cart me over there. And then they would dirty me up and make me cry.'

When he was seven, after his parents had drained most of the family's resources in the Tiger's Head pub next door, his fiery Irish father left abruptly in search of a new life in America, while his mother dragged him and his sister from one boarding house to another as she sank inexorably into alcoholism. This unhappily peripatetic existence lasted for a year or so until an impoverished Mullins Snr, having spent most of his time Stateside drinking hard and sleeping rough, returned to move everyone off to some insalubrious premises in Greenwich so that he could begin work at the docks as a stevedore and part-time petty thief.

He was not a very discerning part-time thief - among his dubious loot was some raw asbestos, a consignment of stale almonds, several bags of inedible brown sugar, one large, live and writhing eel, and a green Amazon parrot - but he was at least more resourceful than his wife, who by this time was often drunk in some or other pub or else at home being violent to the children. Both parents were inclined to let young Dennis do whatever he wanted to do, but only because, as his father once put it, 'I suppose as he is going to finish up in the gutter he might as well have something to do while he's there'.

Dennis left school at fourteen and commenced work as an office boy. That occupation would not last very long ('Mullins,' sighed his distinctly unimpressed employer, 'I'm afraid you are not quite what I am looking for'), and nor would his subsequent stint as a messenger boy. 'My average stay in any job,' he would later admit, 'was about two weeks.'

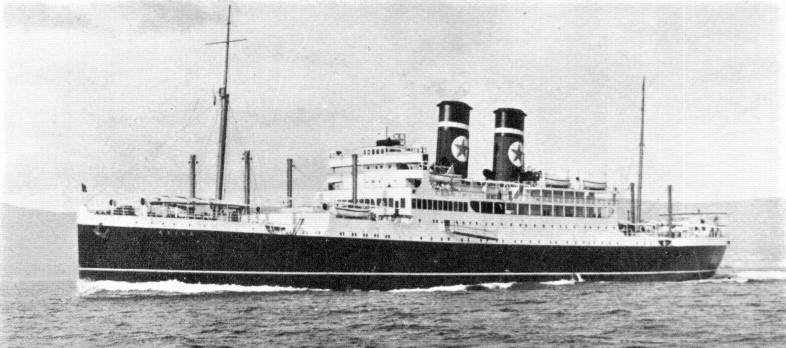

There followed similarly fleeting spells in a remarkably wide range of menial roles, until, longing for some kind of escape, he decided to leave home and try his luck as a galley boy on a cargo ship called the Avila Star. His daily duties on board there would include stoking fires, preparing breakfast, peeling vegetables and polishing brightwork.

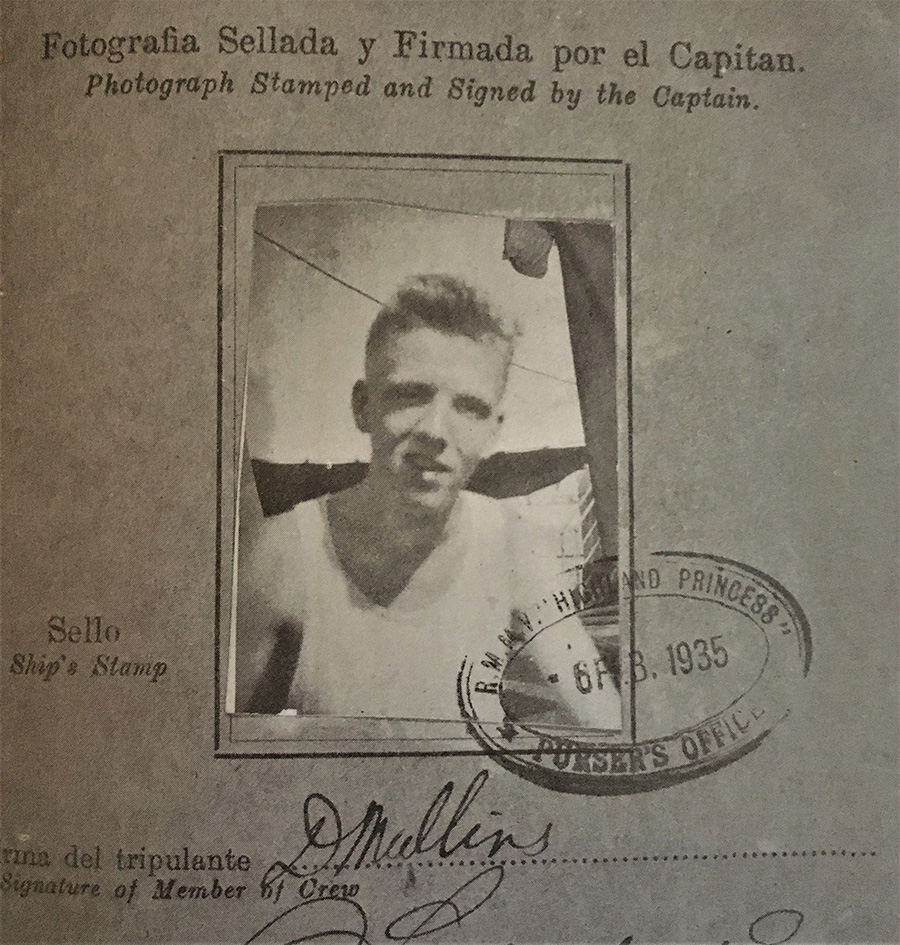

It was his shipmates who changed his name. Someone ended up improvising him a haircut, and the resultant tonsorial eyesore prompted others on board to liken him to 'a bleedin' 'edgehog'. This led to the maritime Mullins first being dubbed 'Spikey' and then 'Spike,' and this was the soubriquet that stuck (the fact that there had previously been a character of the same name - a thief-turned-valet - in a novel by PG Wodehouse - The Intrusion of Jimmy - was entirely coincidental).

They sailed mainly around South America during the next few months, taking in Pernambuco, Rio di Janeiro and Buenos Aries. After a while, once he'd reached the conclusion that everyone else was 'fanatical' about seeing him clean things, he plucked up the courage to complain that he was still only getting about tuppence an hour for his efforts. The ship's large and muscular cook growled back: 'Well, don't tell the owners, because it's a bloody sight more than you're worth and they might want some of it back when we dock!'

He did end up back on dry land in England, but, after discovering his chronically-clashing parents in no mood to welcome him home, he rashly jumped on to the next-available ship - this time a much smaller and dirtier vessel called the Innismoor - and found himself heading first to Arkhangelsk in Russia and then Durban in South Africa, then a bunkering station on Weh Island near Sumatra, and then on to Saigon. It was a gruelling eight-month engagement that obliged him to subsist on nothing more than potatoes (until they went mouldy) and then rice (until that ran out) and then whatever remained among the weevils ('I used to sprinkle tea leaves on my food so that I couldn't see which were weevils and which were tea leaves').

There would be other ships, and other journeys, as he grew from a teenager to an adult, travelling back and forth between Brazil, Río de la Plata and Australia. He visited bars and brothels, learnt to barter, smuggle and fight, and encountered all kinds of quirky and colourful cultures and characters as he sailed from place to place.

This would not, however, prove to be the right route to the future for Mullins. The reason why was because he contrived to get himself sacked by clouting a cook on the head with a frying pan ('When he came out of hospital he was a better person for it. But I got the sack just the same').

Things were no better back home. Coming ashore again in London after four hard years at sea, he discovered that his parents - as if seeking to leave him with the punchline for a joke - had moved without telling him, and so, now alone in the world, he found a room in a local doss-house and flitted in and out of a few dull and poorly-paid jobs (including working as a waiter, a rag and bone man, a labourer on a building site, a factory floor sweeper-upper and a dogsbody in an office) before following in his absent father's uncertain footsteps and becoming a stevedore at the ports along the Thames.

There was still no sure way ahead for him, however, because, in September 1939, the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain 'put into practice his hundred-per-cent way of lousing up a Sunday morning' and declared war on Germany. His appetite for sailing the seas now satiated, Mullins joined the RAF and served the next few years as part of 66 Squadron, scouring the skies above Biggin Hill, Perranporth, Ibsley and Hornchurch.

Following his release in 1945, Mullins launched himself into yet another soul-sapping sequence of short-lived occupations, straining to earn a living by washing dishes in the kitchens at the Grosvenor Hotel, selling programmes in the West End at the Apollo Theatre and waiting on tables at an all-night cafe. By this stage, however, his natural gift for drily comic observations had encouraged him to test his talent as a gag writer, and he started scribbling scripts in his spare time.

Funding himself by working nights at a Waterloo greasy spoon while writing material during the day, he eventually plucked up the courage to send three pages of sample jokes to a popular stage and radio comedian of the time called Vic Oliver. A sort of Anglicised Jack Benny, Oliver relied on the kind of rambling gags to which he could keep returning between various unsuccessful attempts to play something on his violin.

Oliver replied positively - 'the most exciting letter,' Mullins would later say, 'I'd ever had in my life' - agreeing to part with half a guinea a gag, but only if the audience laughed at them. They laughed at enough of them to make Mullins start thinking about turning professional, but when Oliver went on an international tour with a very fixed act the commissions came to an abrupt halt, and the writer went back, in every sense, to waiting.

In 1947, Mullins married Mary McMenamin, a friend of his sister's, and, for the next fifteen years, his writing ambitions were put to one side while he concentrated on earning a steady income. The couple settled in a council house in Brixton, had two sons (Kennedy and Kevin), moved to the countryside in Buckinghamshire (where Spike worked as a farm bailiff) and then, after becoming disenchanted by an accumulation of rural hardships, moved back to London.

Spike, as usual, switched rapidly from one job to another, while sending out, and receiving back, all kinds of plays, sketches, novels and gags. The one thing that kept him going during these times was his conviction that he was meant to be a writer, and he merely considered it 'a pity I had to prove myself a failure at almost everything that everybody else did for a living before somebody recognised me as such'.

He was trying to ply his trade as a house painter when, one tea break in the January of 1963, a workmate named Brian Goom looked up from perusing his copy of the weekly tabloid newspaper Reveille and announced: 'It says here that Max Bygraves is looking for writers to be trained in writing for television'. He suggested that Mullins, who had often muttered about his thwarted ambition, may as well have a go.

The would-be writer demurred, claiming he was getting 'fed up with that lark,' but, once the day's work was over, he picked up the paint-splattered paper and took it home to show his wife. She didn't hesitate before urging him to take up the challenge, teasing him that she would 'never get a mink coat with the money you're earning as a painter'.

He thus sat down, picked up his pen, and started scratching out some sample material, handing each finished page to his wife to copy via her old 'three quid' typewriter. By the early hours of the next morning they had finished, and the seven completed sheets were sent off before the painting started again.

Three days later, they got a reply. Much to their surprise and delight, the envelope contained not only a letter but also a cheque:

Dear Spike Mullins,

Many thanks for the script received this morning, and I am elated with the way you wrote this.

Of course, it is not all usable, but I think a good 40% or 50% is, which is wonderful from a seven-page script.

So as you will not think you are wasting your time, I enclose a cheque for £25.0.0d on account of the script I will get when I have spoken to you and just given you a few more outlets for the comedy.

Thank you once again for your kind interest.

Most sincerely,

Max Bygraves

One week later, Mullins found himself seated at a fancy restaurant in Nottingham as one of Max Bygraves's guests, alongside Sid James and his wife and a couple of other performers, and everyone was praising his work. 'And the thought occurred to me,' he would later confide, 'that so often in my life I've had to say to myself, "Mullins, you got yourself into this, now get yourself out of it". But this time I said, "Mullins, you got yourself into this, now try and stay in it".'

Spike Mullins had finally meandered his way into show business, and would, from this point on, be a busy and increasingly well-regarded professional writer. Aside from the always-supportive Bygraves, for whom he would write loyally and regularly over the course of the next couple of decades, Mullins went on to supply scripts for such performers as Des O'Connor, Bruce Forsyth, Derek Nimmo, Harry Worth, Kenneth Williams, Norman Vaughan, Frankie Howerd, Marti Caine, Mike Yarwood, Bob Monkhouse, Russ Abbot, Jasper Carrott and Tom O'Connor.

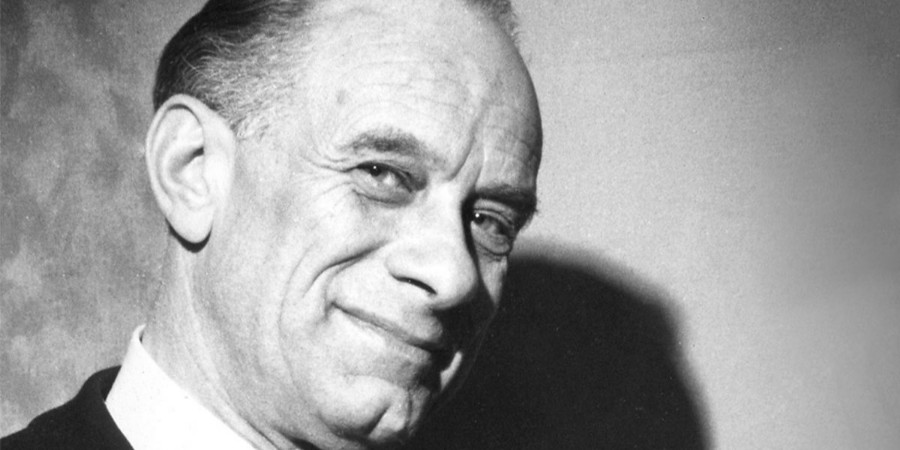

His most creatively fulfilling partnership, however, would be the one that he formed with Ronnie Corbett. A perfect marriage of talents, with Corbett's slow, droll and self-deprecating style of delivery meshing deftly with Mullins's dryly whimsical style of writing, their long-running collaboration would stamp their signatures on to countless prime time Saturday nights.

Mullins first started writing bespoke routines for Corbett in 1969 on a series for London Weekend Television called The Corbett Follies. The comedian already had a talented team of writers working for him regularly - the list included Barry Cryer, Ray Cameron, David Nobbs, Peter Vincent and Dick Vosburgh - but Mullins, in his quietly confident way, was clear about how he could improve certain aspects of the show.

He called the comedian one day, quite out of the blue, and announced: 'I've noticed that when you do your introductions, you waffle a bit. I think I could waffle a bit better for you'.

Corbett, somewhat taken aback, invited him to produce something that might prove it. Mullins proceeded to do so, Corbett read it, and he realised immediately that it did make him waffle a bit better ('He turned waffling into an art form'). A working relationship thus began that would last for more than twenty years, and would provide Corbett with his most popular and personable comedy format.

It would be wrong to suggest that what Mullins did for Corbett was completely fresh and original. It was actually a continuation of a tradition of rambling comic monologues that included the brilliantly disciplined undisciplined discourse that first Eric Sykes and then Galton & Simpson crafted for Frankie Howerd.

What was impressive about it, however, was the elegance of its adumbrations and the vivacity of its vignettes. Each routine was crafted so precisely for Corbett's personality that it seemed - as some viewers indeed came to believe - that the pace and pathways of the patter were dictated solely by the mechanisms of his own mind.

These butterfly-brained monologues tended to oscillate from week to week between two basic options in terms of structure. One was the immediate signalling of a gag (e.g.: 'Now I'd like if I may to tell you a joke about a chap who was driving along the road...') which was then stalled by several paragraphs of digressions ('By the way, this is an original story told to me by one of the chaps they sent round to repair our new cooker...') before being picked up again for the punchline. The alternative strategy saw Corbett get the digressions in right at the start ('Before I begin...') and only acknowledge what he was actually digressing from about six or seven paragraphs into the routine ('...But that wasn't what I was going to tell you about').

Both approaches used the same overtly artful misdirection that Tommy Cooper used for his magic tricks. You knew that he knew that you knew how obvious the end was going to be, and how enjoyably erratic would be the means, so both were complicit in the conjuring tricks.

A particularly memorable example was this clever little nod and a wink to the Wodehousian 'Oldest Member' anecdotes:

Now here is a very funny story about a chap who turns up at this golf course - by the way, I may cry a little while I'm telling this joke, but take no notice. Enjoy yourselves.

Perhaps I should explain that I have recently had to give up golf. For health reasons. My wife was going to kill me.

You see, for some time now she's had this ridiculous idea that I spend so much time playing golf that I'm losing touch with her and our two or three children - little whatsitsname and the other one.

Actually, it all came to a head at about eleven-thirty last night. She suddenly shouted at me, 'Golf! Golf!! Golf!!! All you ever think about is bloody GOLF!!!!'

And I'll be honest: it frightened the life out of me. I mean, you don't expect to meet anybody on the fourteenth green at that time of night.

Honestly, the way she carries on you would think that I was golf mad! For instance, there's her attitude towards my life-size inflatable Arnold Palmer - no, she didn't stick a pin in it, she used to wait until I was asleep and then push it out of bed.

She's even knocked down my little pile of stones in the corner of the garden where I had my vision of Lee Trevino.

However: back to the story.

A chap joins a golf club, and on his first game he tees up and takes a piece of four-by-two out of his bag and whacks the ball straight down the fairway, then hooks it brilliantly on to the green with an old hockey stick, and putts it straight down the hole from twenty-five feet with a piece of rusty gas pipe, blindfolded, while whistling the Hallelujah Chorus - for which, incidentally, my father wrote all the words - well, not all of them - some of them - the best ones.

However, his opponent, upon observing this, not unnaturally becomes full of alarm and despondency, and he can't believe his eyes.

'I can't believe my eyes,' he says.

There - I told you he couldn't.

And the other members are equally amazed. 'Bless my soul,' they say. And 'Fancy that'. And 'Smash his face in'.

I don't know why they said that. But they did.

Anyway, this chap gets round in this manner, easily winning the game by about nine holes.

And his opponent, who has recently paid a hundred pounds for a set of golf clubs, says, 'Look, I'm going back to the clubhouse to cut my throat. Can I buy you a drink?'

To which he replies, 'Thank you kindly,' and sets off walking on his hands with his golf bag of rubbish balanced on his feet.

I bet you're all wondering what is going to happen next. I am, because I've forgotten the ending!

No I haven't.

When they get to the clubhouse, he asks for a large whisky, juggles two pieces of ice and heads them, one at a time, into the glass, followed by a squirt of soda from fourteen yards away, without touching the sides of the glass.

And the president of the club approaches him and says, 'Excuse me, old chap...'

Nice man: Eton - Cambridge - The Guards - and New Faces.

He says, 'We couldn't help noticing the unorthodox manner in which you conduct yourself, and, stop me if I'm wrong, but it is our opinion that you have had it away on your toes from the local Booby Hatch or Laughing Academy'.

At this, our hero held up his hand and said, 'Have no fear, my four-feathered friend, the explanation is simple. You see, I am so incredibly good at everything that unless I make it as difficult as possible I get bored to death'.

At this, another chap said, 'Do you mind if I ask you a personal question?'

He replied, 'I know what you are going to ask, and the answer is: standing up in a hammock'.

What made such material work so well was Mullins's remarkable ability to listen to, and anticipate, the recipient of his writing. He did not just capture the personality of Ronnie Corbett, he paired with his comic pulse.

This was his great gift. All of the best comedians for whom he wrote found that delivering his words was like thinking out loud. He made them seem as natural, as well as funny, as they could be.

Mullins did not look like a laughter-maker himself. A mournful-looking man, with his pale blond hair and silver-white beard, he resembled a garden gnome recently robbed of his fishing rod, or else a casually mugged Father Christmas.

He also had a way of speaking - sad, slow and slightly whiny - that suggested he had survived, or was in the process of surviving, some kind of saturnine experience that had drained most of his energy for discourse. Dick Vosburgh, one of Mullins's friends and occasional collaborators, dubbed him the 'Despond of Slough,' because of this downbeat style of humour and his melancholic moods.

Lurking inside that lugubrious exterior, however, was an anarchically impish spirit who could be a menace in the presence of the pompous and officious. A particularly tiresome BBC governor would discover this to his cost when he met Mullins one morning during a typically intrusive tour of Television Centre.

'How long does it take you to get to work?' asked the governor, much like a monarch quizzing a minion. 'Well, I live in Slough,' Mullins answered cautiously, staring ahead as if straining to sift through all of the relevant details. 'Well, when I say "Slough," I mean a bit outside...Farnham Royal, actually...There's a bus every half hour...ten minutes to the station...but the buses don't always coincide with the trains...Say a ten-minute wait at the station.'

The governor, by this stage, was regretting having ever made such a casual inquiry, glancing at his watch and eyeing the exits, but Mullins, staring solemnly and speaking unnervingly slowly, was clearly only just getting into his groove: 'Twenty-five minutes on the train to Paddington...Then it's the Circle Line to Notting Hill Gate...Change to the Central Line for White City...Five minutes' walk from there...Round about two hours in all, I suppose'.

Then he looked the governor in the eye and added mournfully: 'A long time without a woman'.

The governor, twitching slightly, forced a nervous laugh and moved quickly on. Mullins, who took no such journey (he actually took great pleasure, at that stage in his career, in being collected by a BBC car), sat back contentedly and watched the man scuttle off down the corridor.

He possessed a Peter Cook-like love of daringly dead-pan dullness, probing his prey's patience by meandering in the minutiae, but he could also be, in more convivial company, a drolly engaging anecdotalist to whom his fellow writers relished listening and always loved to quote. Harry Secombe, having heard one of Mullins's rare radio interviews as he drove to a date with a drink, would later say that not even the 'other' Spike could have made him laugh so hard: 'It was such an hysterical occasion that when I reached the hostelry I remained, crying with laughter, inside the car until the programme finished'.

As a writer, Mullins stuck superstitiously to his original working routine. Never taking to typing, he continued scrawling every script in ink, and relied on his ever-supportive wife, Mary, to type each page up ready for its recipient.

As fashions changed and methods evolved, Mullins stood stubbornly firm. Once, while working hurriedly on additional material for a series intended for US television, he handed a new sheet of gags to his American producer, who growled, 'Damn it, this is in longhand! Can't you type?' Mullins replied: 'No. That is something I have in common with Dickens and Shakespeare - I don't suppose you've heard of them.'

A lover of beer and a hater of haircuts, he had been to and gone from so many strange, great and exotic places so much earlier in his life that, by middle age, he was content to stick around Slough, happy in his usual haunts, settled in his fixed circle of friends. The one nod to his world-roaming past was the open vivarium, containing South American lizards, that he kept out the back in his garden.

Ever the jobbing writer, he continued, after his long and celebrated stint on The Two Ronnies, supplying superior scripts for all kinds of formats and figures, but he never pretended that the tougher assignments were anything approaching a treat. 'I'm doing a show starring Jim Davidson,' he told an old colleague glumly when they bumped into each other at Thames TV during the early 1980s, 'but I've told my Mum it stars Heinrich Himmler.'

He was proud of the one time that he was recognised publicly by the profession for his comic achievements - he shared a Pye Television 'Best Written Comedy Contribution' Award with Barry Cryer and Peter Vincent for their efforts on a Harry Secombe Christmas special in 1978 - but his peers ('the writing mafia,' as Barry Cryer called them) were adamant that he should have been honoured far more often.

His memoirs, Me, To Name But A Few (1979), along with some adaptations of his routines for Ronnie Corbett (Ronnie Corbett's Small Man's Guide, 1976, and Ronnie In The Chair, 1978), were well-received, but he had no great longing to have his name hang above any title. So long as people laughed at his jokes, whoever delivered them, he was happy.

When he died, aged seventy-eight, on 18th April 1994, there was a genuine sense of sadness within the comedy profession at the loss of the man Bob Monkhouse had hailed as 'an antic genius,' and whom many of them considered to have been 'the writers' writer'. At his funeral, one of his many friends, Peter Robinson, looked over at the coffin, frowned, and then commented that he was surprised that Spike had turned up, as he famously hated such occasions.

It would only be right, modest though he was, for him to be remembered. Spike Mullins was one of those brave souls who really was there when the page was blank, and he worked hard to write things on it that made a nation laugh.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreSpike Mullins - Me, To Name But A Few

The autobiography of prolific comedy writer Spike Mullins.

First published: Monday 28th May 1979

- Publisher: Michael Joseph

- Pages: 205

- Catalogue: 9780718118020

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 24th July 1980

- Pages: 216

- Catalogue: 9780600201885

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Two Ronnies - The Complete Collection

From 1971 to 1987, over 12 series, four Christmas specials and two classic silent films, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett combined to produce one of the most popular television comedy series ever made.

From their introduction, "And in a packed programme tonight..." to the "Goodnight from him" finale, viewers savoured every moment. The 'Four Candles' and 'Mastermind' sketches, the Piggy Malone and Charley Farley stories and the hilarious musical numbers have a special place in viewers' hearts, but these series are packed with so many moments of comic genius.

This mammoth 27-disc collection contains 93 full episodes of The Two Ronnies, their acclaimed silent comedy films By The Sea and The Picnic, as well as The One Ronnie, Ronnie Corbett's 2010 sketch show featuring Harry Enfield, Catherine Tate, Rob Brydon, Miranda Hart, Matt Lucas and David Walliams.

First released: Monday 17th September 2012

- Released: Monday 14th November 2016

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2 & 4

- Discs: 27

- Minutes: 4,337

- Subtitles: English

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 27

- Catalogue: BBCDVD3455

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

The Complete Up The Elephant And Round The Castle

Comedian Jim Davidson consolidated his phenomenal rise to fame with this hit early-eighties sitcom, starring as a happy-go-lucky Cockney who inherits a house but finds owning his own 'castle' brings its own set of problems.

With guest stars including Linda Robson and The Bill's Christopher Ellison, Tony Scannell and Kevin Lloyd, this set contains all three series.

Jim London is jobless, and he doesn't have much luck with the ladies, either. But he gets his first real break when his Auntie Min bequeaths him her house in South London's Elephant and Castle. 17 Railway Terrace might be small, but bachelor Jim's thrilled to have his own place at last. Sadly, he also inherits a cantankerous, unseen but oft-heard lodger, nosy neighbours and unwanted admirers - and an army of dodgy visitors in need of Jim's help and/or a bed for the night...

First released: Monday 3rd October 2016

- Released: Monday 8th July 2024

- Distributor: Old Gold Media

- Region: 2

- Discs: 3

- Minutes: 530

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: OGM0044

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 3

- Minutes: 530

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: 7954647

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Spike Mullins - Ronnie Corbett's Small Man's Guide

Edited and compiled by Spike Mullins, illustrated by Bill Tidy with cartoons.

First published: Monday 25th October 1976

- Publisher: Michael Joseph

- Pages: 108

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 29th September 1977

- Publisher: Sphere

- Pages: 128

- Catalogue: 9780722125045

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Spike Mullins - Ronnie In The Chair

Written by Spike Mullins, a collection of his original chair monologues for Ronnie Corbett from BBC1's The Two Ronnies.

First published: Monday 27th November 1978

- Published: Monday 1st October 1979

- Pages: 128

- Catalogue: 9780352304278

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Michael Joseph

- Pages: 120

- Catalogue: 9780718117436

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.