You'll all be doing it tomorrow: The strange ways of Roy Jay

Whenever a new comedian is introduced as having 'a style that's all of their own', the alarm bells ought to start ringing. It might simply mean, of course, that he or she really has managed to defy all the odds and find a truly unique way of making people laugh. It's far more likely to mean, however, that the comic in question, instead of concentrating on the content, has fetishised the form, and come up with an act that is more about the gimmick than the gags.

A case in point is the short and very strange career of a man named Roy Jay. He was a very conventional stand-up comic who suddenly started performing in a very unconventional way, and it got him into the public eye only to hurry him back out of it and straight off into obscurity.

He certainly had an upbringing that, in retrospect, appeared ideal for inducing idiosyncrasies. Born in Oslo in 1948, as Roy Jørgensen, to a Norwegian father and a mother who described herself as 'Scottish/Irish', the family moved to South Wales when he was four. At the age of eight, for reasons never fully explained, it was decided to send him to Cork for a year in order to study 'Gaelic and the violin'. Soon after returning to Wales, his family decided to move to Atherton, near Manchester, where he would attend the Hesketh Fletcher High School.

In December 1961, already known to be an enterprising young character, he formed his own 'beat group', Roy Jay and the Jaywalkers, advertising their services in and around the Lancaster area for 'dances and socials'. Upon discovering that there was already a well-established group with the same name, they re-emerged, in a show of defiant adaptation that was destined to define his later career, as The Defenders, and they then broadened their touring travels as far as Morecambe.

Following in his father's footsteps, Jay decided, at the age of fifteen, to quit the band and join the Royal Norwegian Navy, and spent the next two years travelling the world. Returning to the UK in the mid-Sixties, he entered a talent contest, performed a pop song, and won the first prize of £5.

Emboldened by this triumph, he formed another music group. Called The In Sect, he starred as its lead singer as they started playing the northern dance halls. That band, however, soon folded, and Roy resolved to find another way of forging a career in show business.

He had a stab at songwriting, offering his efforts to a number of artists and record companies, but without attracting any interest. There were also a few attempts at stand-up comedy on open mic nights in the local pubs, although the stress of such events usually saw him end the evening too drunk to remember the reaction.

In 1968, Jay joined the resident entertainment team at Pontin's holiday camp at Middleton Towers in Morecambe, and then moved on for longer spells first at the same company's resort at Ainsdale in Southport and then at the Pontin's base at Camber Sands in East Sussex. He did all the usual duties expected of a Bluecoat - socialising with the campers, organising talent contests and other recreational events, and assisting the other cabaret acts - and he also performed, mainly as a singer but also, increasingly, as an impressionist and comedian.

By 1971, although not quite yet finished as a Bluecoat, he was touring the provincial club circuit with a fairly standard stand-up act, sharing the bill with everyone from up-and-coming glam rock bands to ageing strippers. It was a tough apprenticeship, in an environment in which the arrival of the hot meat pies often excited the audiences far more than anything that happened on stage, but Jay hid any sense of discomfort he might have been feeling and, in time, proved himself able to deal with, and sometimes even win over, some notoriously intimidating crowds.

It was through observing so many other comics performing similarly run-of-the-mill routines that Jay came to the conclusion that, as his material was much the same as theirs, his best chance of standing out from the crowd was to find a more distinctive way of delivering the usual glut of gags. What therefore followed, over the next year or so, was a period of intense experimentation in which he tried out as many plans and poses as possible, from stepping off the stage and doing part of his act amongst the audience to riding in a circle on a child's bicycle.

This spirit of twitchy adventurousness, though inevitably hit and miss, started, on the good nights, to get the desired results. Singled out by one critic (who was present when he played the Doncaster Ki-Ki club) for his 'manner that was everything but static', he was praised for the energy and invention that he invested in his performances: 'He registers as a very likeable individual who has little difficulty in holding his audience. And while his slightly unconventional approach gives the act an extra edge, his major assets are undoubtedly his delivery and timing, plus the fact that one never knows quite what is going to happen next'.

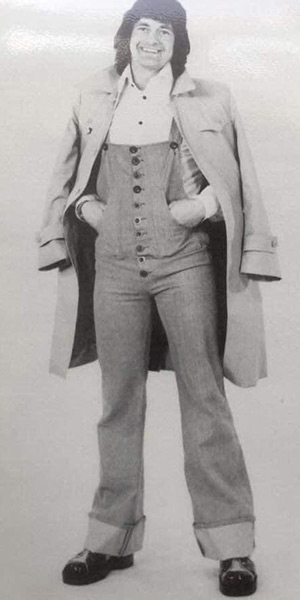

By the end of 1973, having effectively edited his act and image while on stage, he had settled on a costume - a bright yellow boiler suit - and a routine - which featured some planned audience interaction, a few impressions, some pacey patter (decorated with the attempted 'naughty' catchphrase ''Kin 'ell!') and, by way of a finale, an Elvis Presley King Creole parody - which together disguised the derivative nature of his material so well that the dazzle was driving out the doubts. 'Roy Jay must be rated as one of the most modern of today's young entertainers', enthused a reviewer in The Stage. 'It can only be a matter of time before he has a TV break.'

That prediction would only be proven correct if, by 'a matter of time', it meant 'quite a long time', because, in spite of several more very positive appraisals in the press, Roy Jay was left to wait in vain for his break. One year on and, now billed as 'Norway's King of Comedy', he was still touring the clubs, providing the support act for the likes of a group of Polynesian singers in Hartlepool, The New Vaudeville Band in Derby and The Black and White Minstrels in Wolverhampton.

Clearly restless, he continued to try different styles and images, looking for that magical mixture that would spark him into stardom ('I was always searching', he would later reflect, 'for something that hadn't been done before'). He switched from the lively to the static, from the aggressive to the meek, from the mature to the childish, from the visual to the verbal and from the camp to the macho. He concentrated for a while on singing, at other times on impressions, and he even had a brief spell working alongside another up-and-coming comic, Dustin Gee (the future professional partner of Les Dennis), as a musical-comedy double act.

Having gone through two failed marriages, and always struggling for money, there would be many times when, at least for short periods, his self-belief would be shaken so much - there was even one occasion when all of his hair fell out from the stress - that he distracted himself with drink. 'I was getting depressed and downhearted by being given the big elbow,' he would later say. 'I was drinking twenty-four hours a day. I used to go to bed with two strong bottles of lager and a bottle of rum in case I woke up in the night.'

Somehow or other, however, he would struggle back to sobriety and start the fight for fame all over again. He simply couldn't abandon the dream.

At the start of 1976 he tried his luck performing in South Africa as the support act for the local pop group Four Jacks and a Jill. It did not go too well. After playing for three months to a succession of generally lukewarm audiences, he was mugged outside a club in Johannesburg and was later found unconscious about a mile away from the building. Once released from hospital he returned soon after to England with a row of stitches down one side of his face and an arm that had been broken in two separate places.

Undeterred, he went back again towards the end of the year, this time as the support act to the French crooner Charles Aznavour. There was no violence this time around, and he did make a couple of appearances on South African TV, but the reaction of the audiences was much the same as before.

Back in Britain again at the start of 1977, he was found and befriended by the agent Chic Murphy (who, as his personal manager, would be a crucial advisor and steadying influence in the years ahead), and began getting better bookings on the UK circuit, but those critics who had witnessed his multiple reinventions (he was currently going through a 1950s Teddy Boy phase) were beginning to show their exasperation at his apparent inability to fasten on a formula that would help him to really progress. 'Roy Jay is undoubtedly a young artist of enormous potential', wrote one long-standing admirer, '[but] what he needs to do most is to simmer down his frenetic approach and to sort out some of his comedy which, while fresh, is inclined to be repetitious and harps strongly on matters which are more calculated to shock than amuse through their wit.'

At this stage, the thought that will almost certainly be nagging away at you, dear reader, is this: 'Is this story ever going to actually get anywhere?' The truth is that, at the time, the very same thought was probably nagging away at Roy Jay.

His Sisyphean saga continued into 1978 at the less than glamorous Silver Skillet Restaurant in Maidenhead with him now being described (by himself on his bill matter) as a 'sensational new comedian'. It was his tenth year in the business.

'We're going to hear a lot more about this good-looking young comedian', opined a reporter who reviewed this show. The cycle seemed set to keep spinning round and round.

This time, however, Jay was convinced that things were going to be different. He had come up with yet another new style.

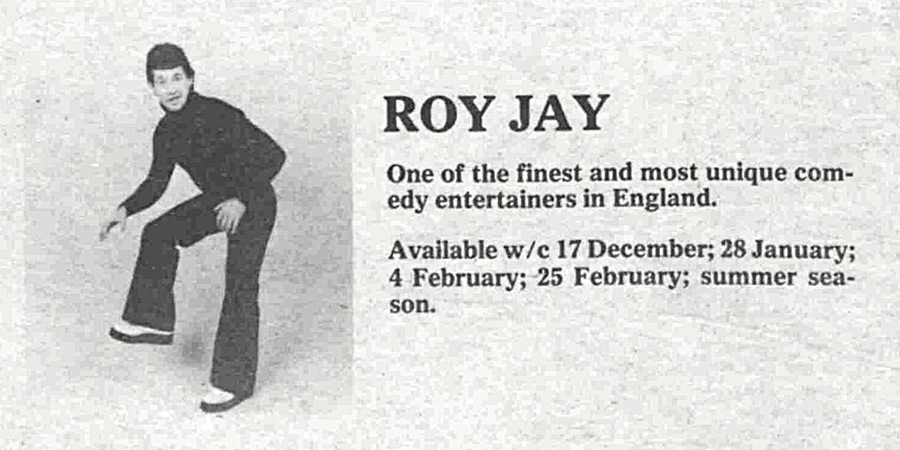

This was the dawning of the age of the 'Slither'. Having found himself new representation in the form of Midland Management (where his fellow acts included the 'harmonica comedian' Johnny Stafford, the 'vocal entertainer' Carlo Santanna [sic] and the 'outstanding boy/girl comedy double act' Mouth and Trousers), Jay had reinvented himself once again, this time as a circumgyratory stand-up.

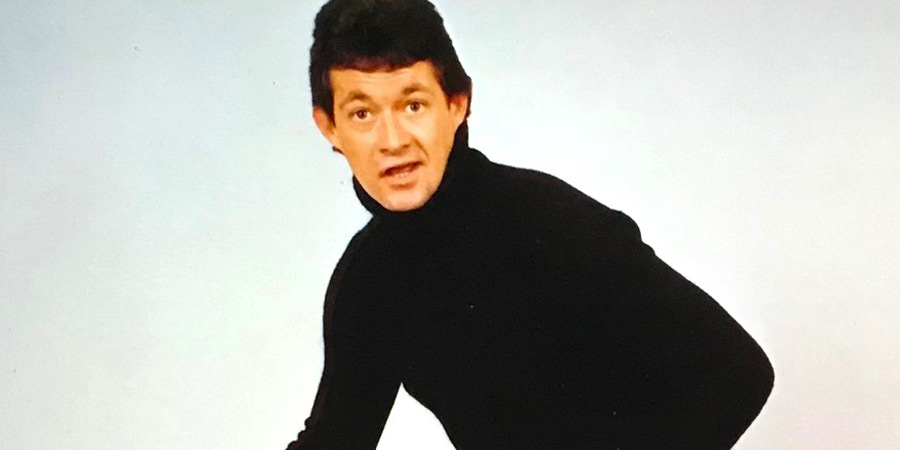

Donning a sleek black polo neck sweater, black trousers and black and white 'brothel creeper' thick-soled shoes, emphasising his eyes with black eyeliner, and assuming a cod-American accent, he would acknowledge the audience by saying, 'Hi, weirdos!', then smile and sashay across the stage, head rocking happily from side to side, his bottom wiggling and jazz hands waving, as he said 'Slither - Hither!', told a couple of gags, suddenly jumped and shouted 'Spook!' and then, with another 'Slither!', he would sashay away with another joke. 'You'll all be doing it tomorrow', he'd keep saying, as he carried on with the conceit.

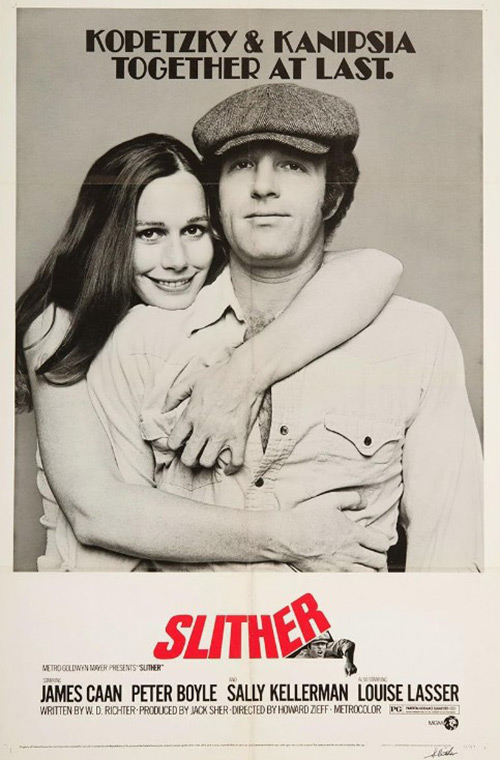

The distinctive walk had been inspired by a black gardener he had encountered in Johannesburg. 'He was so cool', Jay would say, 'he remained in my memory.' The 'Slither!' catchphrase was taken from the 1973 James Caan movie comedy of the same name about an ex-convict struggling to go straight.

It was his most peculiarly coherent gimmick so far. His gags were mostly the same ones that he - and plenty of other club comics - had been using for years, 'borrowed' from the likes of Ken Dodd, Chic Murray, Les Dawson and Dave Allen, but the sheer strangeness of his movements provided sufficient distraction from the blandness of what he was saying. It was like offering people an old pile of chocolates in a shiny new tin, and, much to Jay's delight, they seemed to consider it a treat. 'Slither', he kept saying, and they kept looking and laughing.

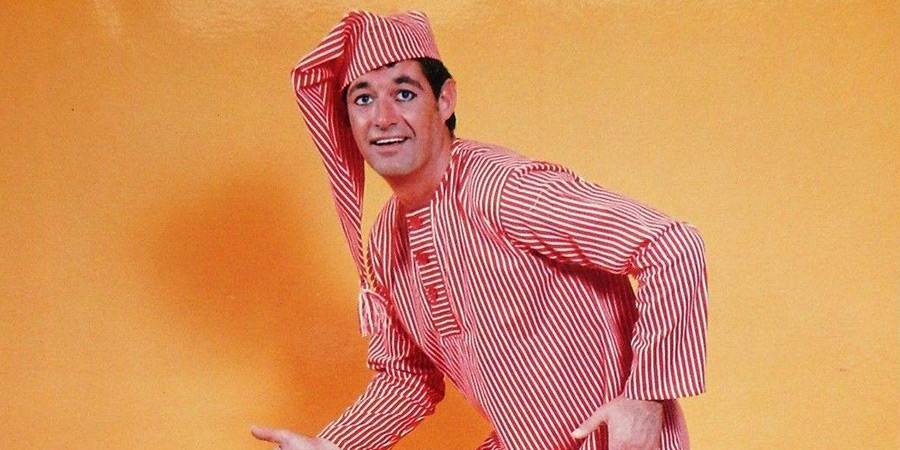

Further refining the act as the audiences grew larger and more appreciative, he put on an old Hollywood-style prison costume, wore white gloves and yellow socks to better catch the attention, moved in and out of a spotlight like a convict on the run (a possible homage to the Band on the Run album cover that had been a favourite of his during the struggles of the Seventies), and arranged for a woozily 'funky' musical accompaniment that was heavy on the bongos and bass. It worked, making the spectacle sharper and more suggestive, and got more and more people talking.

'He is like no one else', the critics, as if stunned by a magician's sleight of hand, declared yet again, 'and this is why he is tipped for major stardom when his opportunity comes along.'

'This unique, original and very funny guy has taken clubland by storm in the last few months,' wrote another excited observer in April 1981. 'All Roy Jay needs now is the "break" into television.'

'At a time when the British cabaret business is desperately looking for fresh faces and new talent,' opined a third observer, 'I can't help wondering why Roy Jay isn't at the top of the ladder. Television producers, please note.'

He had heard it all before, but the difference, on this occasion, was that the recommendations kept on coming and the momentum kept on growing. The name of Roy Jay, this time around, wasn't going to go away.

It was going to happen, he allowed himself to believe. After all this time, after all those tries, this time, at long last, it was actually going to happen - and it did.

In May 1982, the lead singer of The Three Degrees, Sheila Ferguson, signed him up to her new agency, International Music Associates, and made him the support act for the group's forthcoming UK tour. Then a producer/director at Central TV, Philip Casson, added him to the cast of one episode of the new series of the variety format Starburst.

The longed-for break into TV was realised. On 22nd September 1982, reaching through the small screens to a massive audience, Roy Jay finally reached the big time.

Not everyone, now that he was up in front of the nation for inspection, was impressed. Some, staring straight through the style and concentrating coldly on the content (which featured such lines as: 'I went into a wine bar. Everyone there was whining...Slither!...They had been educated at Eton. And graduated to drinking...Spook!'), could hardly have been more dismissive. The TV critic of The People, for example, panned his performance, describing him as 'a ridiculous twerp' and 'the unfunniest man on the box'.

Others, however, found him refreshingly different and endearingly silly. Many children, especially, warmed to his air of mischief and harmless oddity, and soon the words 'Slither!' and 'Spook!' could be heard being parroted in school playgrounds all across the country and the strange zig-zaggy walk was imitated in the presence of countless parents.

Eager to exploit his belated fame, Jay made use of his connections with The Three Degrees to secure some recording facilities and self-funded the making of a fairly 'straight' single featuring his adopted theme tune, a cover of the old Ides of March hit called Vehicle, which he released late in 1982. This was followed by a deal with a budget label to record an entire album, simply called Roy Jay, which was let loose on the public soon after.

1983 would be an even better year for him, with another prime-time appearance on Starburst, as well as a guest spot on the similar BBC1 show The Main Event. He really cemented his success, however, when he reprised his main routine on The Bob Monkhouse Show.

Broadcast on BBC2 on 14th November, and staged and filmed with unusual care and attention to detail, it would certainly be his most polished, and arguably his most memorable, performance on television.

Monkhouse introduced him, almost inevitably, by declaring: 'I really find it very refreshing when I see a new comedian arrive on the scene with a style that's all his own. And I'd like you to share that rare pleasure with me now. Here's Roy Jay!'

Then came this 'new' comedian, who had been treading the boards in the clubs for about fifteen years, discovered and deserted repeatedly, now aged thirty-five and looking, if anything, a little older, armed with all the old jokes but with the new style, determined to make the very best of this moment in front of the camera:

Hi, weirdos! Spook! I used to be a schizophrenic, but we're both okay now...Wow, this place is weird, huh? Slither! I met a guy outside tonight - Slither! - on his way to the Olympic Games. I said, 'Are you a pole vaulter?' He said, 'No, German - but how did you know my name?'... I boogied on down to the disco - Boogie! - You'll all be doing it tomorrow! - Met my brother, Spike. Spike spoke - SPOOK! - He said, 'Hi, Roy J.' - He remembered me! - Spike's weird. He had a pumpkin under his arm. I said, 'Hey, Spike, what are you doing with the pumpkin?' He said, 'Is it twelve o'clock already???' SLITHER! He's weird. I've gotta talk to someone about it. He crossed a Rhode Island Red with a crystal ball. Now he's got a chicken that gets in touch with the other side of the road!...Went to a weird disco. SPOOK! Saw this weird chick. Wow! She was so weird she was putting Grecian 2000 on her legs. She was so thin her boobs were in single file. I said, 'Hey, babe - slither!' She slithered - You'll all be doing it tomorrow! - She said, 'I'm a librarian'. I said, 'Have you anything by Harold Robbins?' She said, 'Yeah - twins'...

He did eight minutes in all - his best material, which was generally fairly prosaic material, but he sold it well, and he made a good impression. The appearance led to him being booked as a guest on Little & Large's Christmas special, where his burgeoning popularity was acknowledged by a special sketch in which Eddie Large, in the now-familiar convict's costume, joined him to mimic his act.

Jay became even more familiar to the broad audience the following year when he started being featured in several lucrative TV commercials, which would include campaigns for Schweppes sparkling drinks and Smiths square-shaped crisps. He also kept up his guest spots, as well as some regular appearances on The Laughter Show, which was hosted by his old friend and partner Dustin Gee along with Les Dennis.

Jay had made it, and, determined to enjoy his hard-won fame, he started drinking more, and taking drugs more, and partying more. It was a fairly understandable reaction, given how many years of disappointment he had endured, but, in purely professional terms, it was not the right time to loosen up and relax.

This should have been the point when he brought in a writer, or two, and started freshening up and improving the quality of his comic material. Instead, he appeared content merely to add every now and then the odd gag he'd heard from another performer, but otherwise rely on his personal charm and the slowly-eroding novelty of his style to maintain his momentum.

The consequence was that his progress was replaced by problems. First, he was distracted by chronic money problems. Always hopelessly ignorant about business matters, and with a weakness for gambling, he had been declared bankrupt back in 1980, and, even though his subsequent stardom saw his income improve enormously, he remained dogged by debts throughout his time in the public eye, and his bewilderment about that fact was a major reason for him going back to the bottle.

Second, as the booze began to intrude into his work, he began to acquire a reputation for unreliability. A scheduled advert for Smiths crisps, for example, was scrapped when he arrived more than a little worse for wear and was judged unfit to film; his place was taken, without any changes to the specially-written 'It's weird' script, by Lenny Henry.

Then, like many club performers once they've grown accustomed to the greater respect and better behaviour of the studio audience, he became resentful of the volatility of the theatrical experience. The kind of heckles that, years before, he would have relished swatting down now just rattled him, and, without the catalyst of the cameras, the adrenaline no longer seemed as easy to summon for an evanescent cabaret engagement.

The cruel irony was that he was giving interviews during this period that were all about how fame had 'saved' him. 'I've been fantastically lucky to have been given a second chance in life', he told one journalist in April 1984. 'I used to be so drunk I didn't know what time of day it was or where I was. Friends used to find me slumped in some dark alley.'

Reflecting on how far he had come from those dark days of obscurity, he said, 'I suppose I'm a survivor'. Sadly, just a few months after he said these words, he would sabotage that very sentiment.

Late on Wednesday evening, 29th August 1984, during an appearance at the plush Inn on the Park club in Jersey, his usual carapace of composure gradually began to crack. It started when some members of the six-hundred-strong audience - who by now, thanks to all the television exposure, were very familiar with his routines - began heckling him loudly, shouting over his punchlines and interrupting his patter with their own random 'Spooks' and 'Slithers'. He dealt with it deftly enough initially, getting some extra laughs while doing so, but the heckles simply got louder and louder, ruining the mood of the moment.

There was also a photographer who, for some unknown reason, had been given permission by the venue's management to roam around close to the front of the stage taking pictures during the act. Struggling to shut out all the clicks that accompanied the snapping, Jay again tried to dismiss the distraction with humour, but, again, the noise continued to niggle.

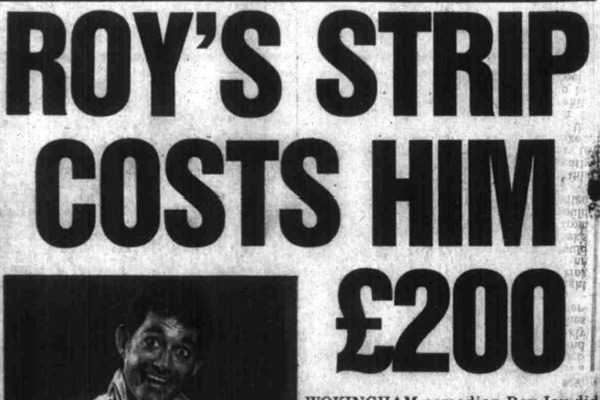

The tension tightened with every tick and tock of the clock until, quite disastrously, he snapped. Sighing at the sound of one more heckle (someone shouted 'Get 'em off!'), he dropped his trousers and (as he was not wearing any underpants) exposed himself.

Among the shocked audience were two off-duty police officers, who had come for a night out with their respective families. Acknowledging the complaints from several other spectators, they called their station, a couple of colleagues arrived, and Jay was arrested.

He spent the night in a St Helier cell - rather aptly still clothed in his comedy convict's costume. The following morning, at the local magistrates' court, he was fined £200. Back in Britain, his panicking agents rushed out a somewhat rambling public apology: 'He is sorry about it. He wishes it hadn't happened. It was one of those things. He was pushed so far. He should not have done it but that is what happened unfortunately'.

Jay himself then did little to help matters when, after promising to send those who had been offended a personally written apology, he protested that he had been treated unjustly. 'The rumpus was about flashing with an audience that contained children, and the person who reported me had a child,' he told a journalist, 'but the event took place at 12:30 at night, and how many children are expected to be in a night club then?'

Digging himself even deeper into a hole, he then proffered a poem about the incident:

One night in Jersey a-slithering

I stepped right out of line

A heckler shouted 'Get 'em off"

And so I did oblige

Accused of a flash and a moonie

Spook Spook man was sent to jail

No bed, no pillow, no water

And nobody would stand my bail

In front of the judge next morning

He called me names abrash

He said you can have eight years in the nick

Or 200 quid in cash!

After being suitably admonished by his own horrified representatives, a damage limitation operation was put into action. Jay was ordered to sober up, keep a low profile for a couple of months, and learn his lesson. When he returned to performing, a roadie was charged with the task of keeping him away from any alcohol.

It seemed to be working. The story faded away surprisingly quickly, Jay was invited back on TV, and the theatre engagements went by without any further incidents.

The following year, however, would see a gradual decline in his fortunes. He was quietly dropped from The Laughter Show on the grounds that he had struggled when required to deliver scripted material straight to camera, the effects of his drinking were starting to show, and, more generally, it was felt that the 'Slither' routine was getting somewhat stale. With fewer offers of similarly high-profile work, he sensed where things were going, and was sucked back into the old spiral that led straight down the neck of a bottle.

In February 1986, after several months' absence from TV screens, he appeared on the BBC's daytime show Pebble Mill At One to mime his way through his new single, Spookin' Down The Street. He looked depressingly unwell - a puffy face, sweating profusely right from the start, with sluggish movements - as he laboured his way through the routine.

One month later, his application for a discharge from bankruptcy was refused. He still played the clubs, still billed as 'TV's Slither Man', but any cachet was crumbling fast. He was slipping back down the levels, back down the leagues, back from where he had come.

By now, after just four years of fame, it was all falling away. Falling away so fast.

He relocated to Spain's Costa Blanca, partly to escape his creditors, partly to lick his wounds. He was still more than good enough to get work there, the pay was quite decent, and its cluster of Anglo-centric holiday resorts provided him with a ready-made, good-natured, audience. With the pressure off, he felt free to bask in his own little bubble of local adoration each night, while drinking away the pain each day.

By the late 1980s, now based in Benidorm, he had settled into a residency first at The Talk of the Coast and then at the nearby Chaplin's Bar, using 'bluer' material, while sometimes also providing support, so to speak, for a ping-pong ball-propelling erotic dancer - hailed as 'legendary' among some sun-struck ex-pats - by the name of Sticky Vicky at the Red Lion and numerous other venues in the area. He would still slip back to Britain every now and then (supposedly 'fresh from a European tour') to play the odd club, but they would be decidedly low-key affairs at minor venues in places such as Daventry, Codnor, Belper and Long Buckby.

A sign of how far he had fallen into obscurity in the UK came with a reader's letter in the Daily Mirror, published on 12th February 1993, asking if anyone knew who the 'Slither' comedian was who used to be on television. A member of the newspaper's staff replied: 'He is called Roy Jay and it took ages to find that out. No one seems to know what he is doing now'.

As his health deteriorated, with growing weight and breathing problems, he finally gave up the 'Slither' persona and settled instead on simply sitting on a stool and telling family-friendly gags. He could never give up entirely; he had nothing else in his life. In his final year or so, he was wheelchair-bound and reliant on an oxygen tank, but he was still on stage, still seeking the laughs.

He died in Alicante in December 2007, alone and penniless, aged just fifty-nine. His funeral was paid for by money raised by his many friends and admirers in the local area.

What lesson, if any, can we take from the strange, rambling, slithering, story of Roy Jay's slow rise and rapid fall? It is tempting to suggest that what his sad fate teaches us - performers and punters alike - is the importance of valuing the crafted over the cursory, and substance over superficiality. We might even be tempted to say 'that was then, this is now', and pat ourselves on the back for how much more discriminating we've become.

Then again, in our own age, in which the likes of innumerable forgettable reality TV 'stars', endless YouTube 'influencers' and cynically opportunistic box-tickers have not only been allowed but in many cases positively encouraged to carve out a lucrative niche in mainstream popular culture, and the likes of such startlingly shallow creations - for want of a better and more deserved word - as 'Keith Lemon' have been able to claim an alarmingly stable and long-term TV career, are we really in any position to sneer at someone who, back in the day, managed, after so long a struggle, to prise a brief but precious period in front of the spotlight?

'You'll all be doing it tomorrow.' How pathetically true that prediction turned out to be. Many are indeed doing it, these days, every day, and getting away with it, at far less personal cost, and to so much more unearned advantage.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more