The many meals of Robert Morley

There are some people who eat to live. There are others who live to eat. Then there is Robert Morley, who did not merely live to eat but also made a living out of playing people who lived to eat.

No other actor appeared so often on the screen with a napkin wrapped around their neck. It was as if an extra-large portion of Robert Morley's public life was an ongoing audition for the role of Mr Creosote in Monty Python's The Meaning Of Life.

It was much the same off the screen. Here again food, more often than not, seemed to loom larger than art when it came to deciding what it was worth him actually doing.

In 1951, for instance, he persuaded BBC TV to broadcast a pioneering sitcom he had written entitled Parent-Craft. Although he happily agreed to all of the standard production arrangements, he spent a further few weeks arguing passionately that the Corporation should commit to supplying a 'full high tea' to all of the cast.

The same sort of thing was still happening twenty-two years later, in 1973, when he was invited to be a guest on The Morecambe & Wise Show, and he was far more concerned to sort out his lunch than study his script. Guest performers on this high profile show were usually obliged to travel to the corporation's notoriously unglamorous rehearsal rooms - situated in a cabbage-scented community centre in the middle of a run-down council estate uncomfortably close to Wormwood Scrubs, where the only food made available was the standard working lunch of pea and ham soup and a plate of cheese sandwiches - and graft for at least a week to get the comedy exactly right.

Morley, however, was different. He reacted on the first day as if he had just wandered into a war zone, and only coped through subsequent sessions by ensuring that a very large hamper from Fortnum & Mason was delivered every day by noon, when, much to the two stars' surprise and frustration, he would stop work and settle down to a long and leisurely three-course meal, accompanied by half bottles of Margaux, Pouilly-Fumé and Sauternes and finished by one of his favourite puddings ('For me,' he liked to say, 'two of the most awful words in the English language have always been "just coffee"').

This was much the norm for Morley. He had little time for directors ('Such useful fellows,' he liked to say; 'they take your coat in the morning and hand it back at the end of rehearsal'), and usually, although he was an occasional playwright himself, little time for the script (his standard trick was to place the unopened envelope in the palm of his right hand, assess it for weight, and then, if it seemed too heavy or too light, drop it straight into his waste basket).

It was always the catering, he liked to claim, that concerned him most: if the production was based either at a traditional studio with a proper in-house restaurant, or else at least at a location in quick and easy access of Le Caprice, then he would probably consider consenting to take the part. If it was situated anywhere else, then he would have to send someone to scout the area for suitable epicurean treasures before even thinking about signing up.

Aside from lacking the usual amount of actorly motivation, Morley was also not, it has to be said, the most versatile of performers. It took, predictably, the peerlessly rude Rex Harrison to render this widespread observation painfully audible when - supposedly in praise of his thespian friend - he summed up Morley's 'very stable' life thus: 'One wife, one house...and, come to think of it, one performance, too'.

What Morley did do, however, he did so well that he was one of the most in-demand comic character actors of his generation. He could play the bumbling and bemused boss (such as the easily-dazzled tweed company owner MacPherson in The Battle Of The Sexes) and the unctuous and untrustworthy rascal (such as the pompous 'Fat Gut' Peterson in Beat The Devil) very well, and he could portray the buoyant, if somewhat buffoonish, bon vivant quite brilliantly (as he did in countless plays, movies and commercials in a career spanning just over sixty years).

What he did best of all was articulating appetite. If the camera's aim, with most actors, is to photograph thought, then in Morley's case it was to photograph insatiable human hunger. No one else could convey a sense of keen gustatory anticipation quite as well as Robert Morley. His eyes would widen, his nostrils flare and his lips start to glisten whenever he caught sight of the latest selection of delectable comestibles.

Each culinary-related appearance thus seemed like part of some elaborate Catholic parable about the dangers of succumbing to gluttony. Once the taste buds were engaged, the brain was enslaved, and his character seemed sadly but inescapably destined to end up roasting slowly, like a wild boar on a spit, over the red-hot coals of Hell.

In an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, for example, entitled Speciality Of The House (1959), he played Laffler, whose love for the finest food is so deep and devout that he even sees menus as unwelcome obstacles to experiencing the full authenticity of its appreciation: 'Some printer prints, some head waiter writes words on a card. What do they mean? "Sauce Mornay," the menu tells us. Who can say with what love and care the béchamel was prepared from which the Mornay is derived? Who can say with what tenderness the cheese was grated? Who can say whether the result will be a delight or a disappointment?'

Laffler is a preeningly proud member of Spirro's - a private dining club so exclusive that it is hidden away deep in the darkest of shadows down by the docks, admits no more than forty members at any one time, and only serves one main dish for dinner each day ('always different, always superb'). Waxing lyrical about the 'mystery and dignity' of this magical place ('Here at Spirro's, we have no doubts, we ask no questions - we only know that there is a genius in the kitchen!'), he is obsessed with the speciality of the house, 'Lamb Amirstan,' which is prepared, according to legend, only with the finest and most succulent lambs sourced from a 'small but superb' flock perched high on 'a desolate plateau on the border of Uganda', and is marinated for no fewer than three whole days.

Hoping that he might soon get to taste this rare culinary creation once again, he invites a business protégé of his, Costain, to dine with him there as his guest, but is disappointed by the fact that, after all of his mouth-watering talk about this 'masterpiece' of a dish, it is not available for that night. 'Oh', he exclaims, his moist mouth pouting. 'I've waited so long now!'

Undeterred, he tells Costain to join him again the following evening ('Tonight,' he says, sniffing the air earnestly in the hope of smelling the richly-seasoned scent of the legendary lamb, 'could be the night!'). Once they are seated, however, Laffler is again frustrated to find that the meal, although inevitably delicious, is still not the speciality of the house.

The owner of the establishment - a large and strikingly androgynous character ('the high priestess of our kitchen') dressed in a dinner jacket decorated with a couple of strange-looking medals - suddenly arrives bearing the good news that the legendary Lamb Amirstan will be served the following evening, and encourages not only Laffler but also Costain to come back to enjoy it. Laffler thus heads home barely able to contain his excitement.

The two men duly return the next night (although by this time the almost helplessly esurient Laffler has become resentful of his guest: 'There'll be less for me!'), and the long-awaited meal is finally served. The taste is so gloriously unique that all trivial personal tensions slip away, and Laffler, almost tearfully contented, sits back in quiet satisfaction.

The following day, still in a blissful state, he arranges to leave the increasingly self-satisfied Costain in charge of his import/export business while he goes on a month-long vacation ('These last few weeks, eating together at Spirro's, seem to have brought us very close'). He then leaves his employee to finish off some paperwork while he, thrilled by the whispered news that he is finally about to be made a lifetime member of the club, heads off in the hope that Spirro has 'one more special treat' in store for him.

Once again, however, he is left disappointed, and, realising that it will now be weeks before he will have a chance of feasting again on that longed-for lamb, is so angry that he demands to see the owner. She duly arrives and is quick to placate him with the promise of an exclusive tour of the usually unseen kitchen 'where the miracles are performed'.

Always an eager exponent of haute cuisine one-upmanship, he wastes no time in taking her up on her offer and, while his fellow diners watch him jealously from their respective tables, he scuttles off to the place where all of the magic happens. Once inside, however, he sees that the chef is standing there, waiting for him, holding a very large and sharp meat cleaver.

Costain, meanwhile, has arrived on his own. Spirro greets him warmly, and, while glancing at a newly-framed picture of their mutual 'absent friend', she assures him that the speciality of the house will be served up again very soon.

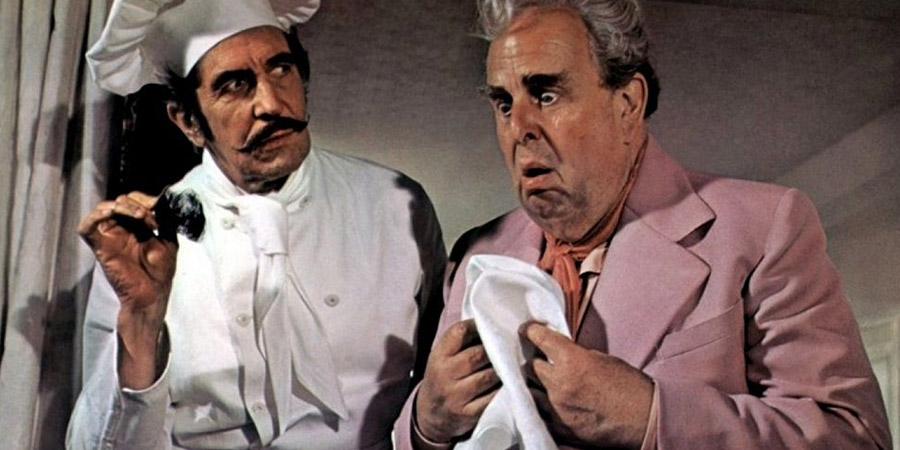

Much the same sad fate would meet the character that Morley played in the cult comic-horror movie Theatre Of Blood (1973). It featured his fellow foodie Vincent Price as the deranged classical actor Edward Kendall Sheridan Lionheart, who, after being humiliated by a group of pompous London theatre critics, is determined to take revenge by dispatching each one of them in the manner of a tragic scene from a Shakespearean play.

Morley appeared as Meredith Merridew, a quite ridiculously camp and bouffant-haired gourmand decorated in various shades of pink, who arrives home one day expecting to be greeted by his two beloved 'doggie-woggies', but is surprised instead by what appears to be the team from his favourite TV show, This Is Your Dish, who have baked him a special pie. He beams with delight - 'Oh! Oh! Oh! What a divine surprise!' - and is guided to the dining table by Lionheart, who on this occasion is disguised as a goatee-bearded French chef.

Once seated, the chef places a nice thick napkin around Merridew's neck and lights a couple of candles as the salivating critic says a quick prayer of thanks for such a treat. The pie is then served, and Merridew sticks his fork in, scoops up some creamy-covered meat and starts to eat. 'Simply delicious', he gasps between mouthfuls.

'I wonder where my babies have got to', he suddenly says, glancing around, of the dogs on which he dotes. 'I wish they were here to share this with me!' The chef is quick to reassure him: 'If monsieur cannot do without his dogs, then he shall have his dogs'. He walks over to a large and shiny silver cloche, and remarks, 'You see, monsieur, two dogs...[lifting the lid to reveal the heads of a pair of poodles poking up from inside the pastry]...two pies'.

Merridew leaps up in horror, spitting out semi-chewed chunks of canine as he rushes over to see what remains of his precious pooches. 'Do have some more', snarls the chef, as he pulls off his fake beard and reveals his true identity.

Lionheart, adapting the death scene of Queen Tamora in Titus Andronicus, then pushes Merridew down on to the table and force-feeds him his pets through a large copper funnel. It is, in a sense, a case of a pig being finished off by an old ham.

'Pity,' says Lionheart with a satisfied smirk as he gazes at what is now the corpse of the critic. 'He didn't have the stomach for it.'

Arguably Morley's finest fine dining fiction of all was the 1978 movie Who Is Killing The Great Chefs Of Europe?. He played Max Vandeveer, a spectacularly pompous and 'calamitously fat' publisher of a gourmet magazine called Epicurious, and the sort of person who pokes a bell button with his walking stick in order to signal his presence at someone's door.

The patron of four internationally eminent European chefs, each one of them especially renowned for their signature dish, he is proud to be commemorating their achievements, and his own role in promoting them, not only in a special edition of his magazine, but also by featuring their food in a royal banquet he is organising for no lesser a figure than the Queen at Buckingham Palace. 'Once Her Majesty tastes your Baked Pigeon En Croûte', he tells one of these inimitable cordon-bleu artistes, 'nothing stands in the way of the knighthood for which I was so maliciously passed over last year!'

His addiction to ingesting all of these mouth-watering masterpieces, however, is actually seriously damaging his health. His long-suffering doctor (whom he treats with outright contempt: 'I don't wish to be on first name terms with anyone who's had their fingers up my rectum - however much you may have enjoyed the experience!') reveals that he is now suffering from gout, an enlarged liver, a duodenal ulcer, a spastic colon, a heart murmur and severe hardening of the arteries, and warns that unless he takes immediate steps to lose one half of his present weight he will be dead within six months.

Vandeveer, however, appears utterly unrepentant, and reacts to the desperate request that he at least 'cuts down' on a few of his favourite treats with an explosion of self-righteous vituperation. '"CUT DOWN"?' he exclaims. 'I am what I am precisely because I've eaten my way to the top! I am a work of art, created by the finest chefs in the world. Every fold is a brush stroke! Every crease a sonnet! Every chin a concerto! In short, doctor darling, in my present form, I'm a masterpiece!'

In no time at all, following a few quick upmarket snacks in his chauffeur-driven car, he is back in one of his regular restaurants, claiming not to care and ladling praise on to his latest protégé for crafting him yet another incomparable gastronomic experience: 'Memorable, truly memorable! A late Schubert quintet for the palate!'

One by one, however, Vandeveer's celebrated culinary quartet are cut down. The first to fall is the pigeon specialist from Switzerland, Louis Kohner, who ends up baked in an oven just like his many birds ('Only an amateur', Vandeveer laments, 'would bake anything Swiss in a 450 oven!'). Then it is the turn of the dapper Italian Fausto Zoppi (drowned in the same big tank where his luscious lobsters still swim about), followed by the Frenchman Jean-Claude Moulineau (whose skull is crushed in his own custom-made duck press).

This only leaves Britain's Natasha O'Brien, the glamorous dessert specialist, who is almost blown up by one of her own creamy creations. It turns out that someone has secreted a bomb inside her bombe, and she is saved just before her heated drop of Framboise seeps down and sets it off.

Vandeveer, who has been lurking guiltily in the shadows, realises that it is now just a matter of time before he is rumbled. He thus creeps away, back to his favourite restaurant, where he sits surrounded by every single dish that he has ever desired. As Natasha and the police race in, they find him sitting there, napkin embracing his neck like a comforting friend, blank-faced and motionless: he has, it seems, accepted that final, fatal, wafer-thin mint.

Barely able to speak, he struggles to explain that he simply could not continue to resist the rarefied fare of his favourite chefs, and so, to stay loyal to his miserably ascetic diet, he felt compelled, reluctantly, to dispatch them. 'I was never worthy of any of you', he manages to whisper to O'Brien. 'You created. I just appreciated.' Then, with one last hiccup, he has gone.

The performance (for which he won an award from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association) was arguably Robert Morley's last hurrah as a professional actor. At this late stage in his life, he seemed content to go on to talk shows and lap up the praise ('You can never choke a cat with cream') and generally play up to his on-screen image as the best of all friends of fine food, seeing as it was really only a slight exaggeration, rather than a gross distortion, of his own authentic feelings.

He had several enjoyable spells as a well-remunerated food critic for such high profile publications as Punch and Playboy, which enabled him to breakfast, lunch and dine at some of the best hotels and restaurants throughout the world ('If people take the trouble to cook,' he reasoned, 'you should take the trouble to eat'). He also spent a long and lucrative spell making commercials for Heinz as its 'Mr Soup,' and also made numerous appearances celebrating the 'international range' of Tyson Chicken Entrées.

Rather ironically, seeing as his fascination with food was all about its consumption rather than its production, he even served for several years during the 1980s as the genial but rather erratic host of a cooking show - Celebrity Chefs - on American cable TV (actually, to add to the oddity of the whole affair, it was made by the Christian Broadcasting Network). Sporting a colourful apron and a dazed 'Where am I?' sort of expression, he would attempt to assist his nervous-looking guests as they prepared their signature dishes, while simultaneously asking them various career-related questions.

A visibly uneasy Robert Vaughn, for example, came on ('My dear boy, I am pleased to meet you!') to demonstrate his own distinctive take on Fettuccine Alfredo, whilst trying to plug (rather aptly) a spaghetti western he had just made in Arizona; stand-up comic David Brenner struggled to sulkily complete his Frozen Chocolate-Peanut Butter Torte after Morley began by declaring matter-of-factly, 'I really don't like peanut butter!'; and the redoubtable singer and actor Eartha Kitt came up with a recipe for Crocked Rabbit and Cabbage that, quite specifically, restricted the host's involvement to adding a sprinkle of salt. Probably the high point of the entire series saw Morley shuffle backwards and forwards in mounting alarm while much of the studio kitchen caught fire during the course of another celebrity's over-elaborate flambé.

When he died, on 3rd June 1992 at the age of eighty-four, some expressed the regret that he had, in later years, squandered so great a degree of his considerable comic gifts. As one critic had put it, with such cruel candour, a few years before: 'It is sad when a talented person is so complacent, so self-indulgent, so content to fob audiences off with the third rate when he is capable of the first rate.' They did, it has to be said, have a point.

He had, after all, attracted so much critical praise back in his twenties for playing Oscar Wilde in both the West End and on Broadway, and had followed that with similarly celebrated leading performances as Henry Higgins in Pygmalion and Sheridan Whiteside in The Man Who Came To Dinner. He had also been nominated for a 'Best Supporting Actor' Academy Award for his role in Marie Antoinette (1938), and written two very successful plays, Goodness, How Sad (1937) and (in collaboration with Noel Langley) Edward, My Son (1947).

It was only from the 1950s onwards that he seemed to start losing interest in acting as something more than a means of funding his off-screen activities. 'Acting became for him rather like dieting', his son, Sheridan, would reflect; 'something one really should do more of at some time, but preferably not right now.' Aside from a well-received big screen reprise of his stage triumph in Oscar Wilde (1960), his roles, when he did deign to take them, tended to settle at various points on the scale of self-parody, and he knew it and generally accepted it. 'Anyone who works is a fool', he liked to claim. 'I don't work - I merely inflict myself upon the public.'

Often alongside his long-standing partner in crime, Wilfrid Hyde-White (a man forever being chased from place to place by the assorted forces of the Inland Revenue and a band of angry bookmakers), Morley would throw his money away on race horses, roulette wheels and restaurants, and then have to earn some more by enduring yet another uninspiring movie (although he always insisted on a clause in his contracts that guaranteed him two days off if shooting happened to clash with Ascot week). If ever he won a decent amount he would wait for a while in the hope of a better project, but otherwise he would accept whatever formulaic fare was immediately on offer, as well as, deep into his anecdotage, pick up countless cheques for charming the audiences on chat shows.

The carpings of the professional critics never bothered him. When one wrote acidly of an appearance that 'Robert Morley plays the lead as Robert Morley', he happily agreed: 'The art of character acting is not to look like other people, but to assume other people look curiously like me.' The amateur critics also failed to rattle him: 'I am always immensely cheered up', he once said, 'by letters which start "You fat nit" or "Come off it, Blubberbags". I feel I have been of some use to the community.'

He did not crave adulation or awards. He cared more about the gravied plate than the greasy pole, and much preferred self-deprecation to self-promotion. He even (as a suitably grand Fabian socialist) turned down the offer of a knighthood from Labour's Harold Wilson - partly on the grounds that he was happy to see such a title restricted in theatrical circles to the most eminent of classical actors, and partly because his wife feared that it would encourage local tradesmen to start inflating their household bills.

He just wanted to have fun and enjoy life, and, if he could, in the right role, share that pleasure with his audience. He did that remarkably well whenever he had the chance.

Now he is missed as much as a discontinued favourite dish. There is no one left these days who serves up such a rich mix of traditional British wit, lofty charm, patrician pomposity, childlike playfulness, half-glimpsed vulnerability and a very healthy degree of demotic self-mockery.

'It's much like being a waiter, without having to serve the food or worry about the tips', he once said of the art that he always hid; 'just save the audience from as much agony as possible while they're with you, that's what it's all about, I think.' It was, in his case, a service that came with far greater care than he would ever admit.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreThe Battle Of The Sexes - Dual Format Edition

When American businesswoman Angela Barrows (Constance Cummings) is sent by her company to Edinburgh to look into potential export markets, she meets Robert MacPherson (Robert Morley), a company manager who has just inherited his father's textile business and wants her advice on updating it to modern standards.

Before long Angela is introducing all sorts of new-fangled ideas and the employees, scandalised that they have to work under a female boss, turn to Mr Martin (Peter Sellers), who promises to lead the fight against the interloper.

First released: Monday 20th April 2020

- Distributor: BFI

- Region: B/2

- Discs: 2

- Minutes: 84

- Subtitles: English

- Catalogue: BFIB1377

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

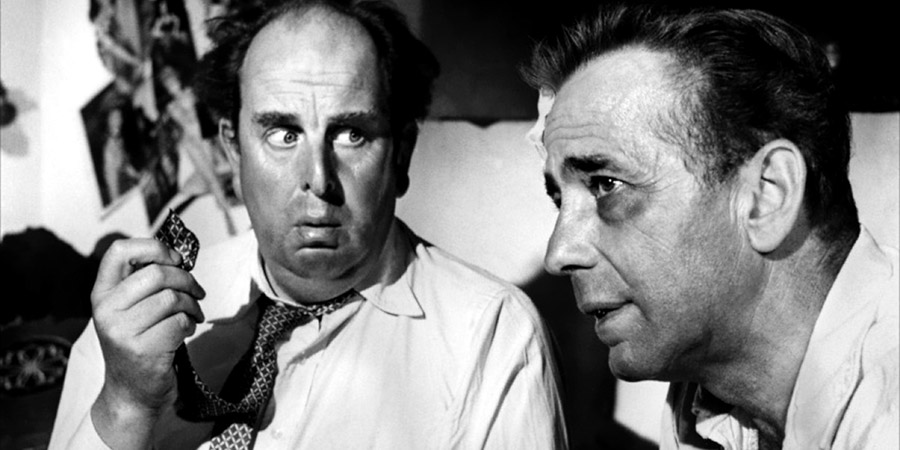

Beat The Devil - Dual Format Edition

As one of a disparate group of fortune-seekers bound for Africa, hard-up Billy Dannreuther (Humphrey Bogart) faces the swindling machinations of his fellow travellers as they await passage from a picturesque port on Italy's Amalfi coast. But with scheming aplenty, will this motley crew miss the boat completely?

Bogart is joined by Jennifer Jones, Gina Lollobrigida and Peter Lorre among the star-studded cast in this classic caper scripted by Truman Capote. A masterful shaggy dog story that's part comedy and part thriller, nothing is quite what it seems in director John Huston's wry send-up of film noir, including his own The Maltese Falcon.

This release is issued from a new 4K restoration by Sony Pictures and The Film Foundation.

First released: Monday 16th March 2020

- Distributor: BFI

- Region: B/2

- Discs: 2

- Minutes: 94

- Subtitles: English

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Theatre Of Blood

Vincent Price has reserved a seat for you in the theatre of blood.

It's never been tougher to be a critic than in Theatre Of Blood, one of the greatest horror comedies of all time. Vincent Price gives a career-best performance as Edward Lionhart, a veteran Shakespearean actor who, when passed over for the coveted Critic's Circle award for Best Actor takes deadly revenge on the critics who snubbed him.

With one of the greatest casts ever assembled for a horror film - including Diana Rigg, Harry Andrews, Jack Hawkins and Arthur Lowe - Theatre Of Blood is an dementedly funny and deliciously macabre cult classic, transferred from original film elements by MGM.

First released: Monday 19th May 2014

- Distributor: Arrow Books

- Region: B

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 104

- Subtitles: English

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.