Lovely Rita: The indomitable Rita Webb

Rita Webb always said that she knew the score. 'The TV men don't hire me for my good looks, do they? If they did, I'd bleeding starve', she once said. 'When they want an ugly old cow, they always send for me. And if I can make people happy by making them laugh at me, then that is reward enough'.

She did rather more than that. Producers expected her to accept negative stereotypes (about women and the working-class) like a magnet welcomes metals, but she subverted them from within. A battler, but no battle-axe, she invested her characters with such a strong personality, and such an engaging sense of self-worth, that one was more likely to laugh with her instead of merely at her.

Rita Webb's working-class women were strong and self-assertive, women who had fought their way through life and were never going to be put down or pushed around. Small-bodied but big-hearted, they were too loud and proud to be dismissed as anyone's figure of fun. Fists on hips, head held high, with that defiantly aggressive exclamation - 'Oi - 'Oo the 'eck do you fink you are?' - she was, in her own inimitably quirky way, an inspiration for anyone trying to cope with the attempted impositions of ordinary social life.

Born Olive Rita Webb at 87 Hartland Road, Willesden, in northwest London, on 25th February 1904, there was no obvious catalyst to engender her passion for performing, but a passion, nonetheless, was soon sparked. 'I always wanted to be an actress', she would say, 'I was an actress when I was three', and she would run away from home, aged fourteen, to become a chorus girl at the Metropolitan Music Hall in Edgeware Road.

'I told them I was twenty-two', she later recalled, 'and they believed me because I had a nice big bust. I looked pretty with my bright red hair and slim figure. And the dancing consisted of cocking your leg to the music. It was dead easy'.

'I used to make all the kids watch me parading up and down', she reflected. 'When they used to say: "Can we go now, Rita?" I used to say: "No, you can't" as I was bigger and stronger than any of them I used to clout them if they wouldn't sit still and listen to me'.

Two months after she had fled from home, however, she was forced back there. The police tracked her down and returned her to her parents.

The flame for fame, nonetheless, refused to be extinguished. She knew the kind of life that was mapped out for her - 'I'd probably end up as a lavatory attendant, wiping the seats or whatever they do' - and was determined to rip up that route and take a different turn of her own ('I was convinced,' she later said, 'I was going to be Sarah Bernhardt's successor').

She finished her time at school, without anyone being left in any doubt that her participation was anything other than perfunctory. 'I filled inkpots with water', she would recall, 'wrote naughty words on the blackboard and generally outraged my teacher'.

From the late-1940s onwards, after grudgingly going through the motions in a number of menial jobs (while sending a stream of hopeful letters off to well-known Hollywood directors), she started spending more and more of her free time hanging around the nearby movie studios in search of work. She was known, by now, as Rita Webb - 'I don't usually use the Olive', she explained in one typically rambling request for employment, 'as it was my father's favourite name, and he is no longer around. Sentimental I know' - and was determined, one way or another, to get herself accepted in the acting profession.

Shaving a full eight years off her real age, she would pen long and chatty letters to just about anyone of whom she had heard in the business, recommending herself as a character actor, by then 'of stout build', who was particularly good at playing Cockney types. If the recipients of such missives were left unsure as to her actual abilities, they must at least have been intrigued by the power of her personality, which poured out of every page.

Eventually, through sheer persistence, she started getting brief and uncredited parts as an extra in such productions as Moulin Rouge (1952), The Silken Affair (1956) and Suddenly Last Summer (1959), usually playing shopkeepers, cleaners, landladies, charwomen, market stall sellers or servants. She also bombarded the BBC with bold and decidedly unconventional requests for work ('Give this gal a chance' being one of her regular pleas), and finally made her radio debut, playing two characters - 'Mrs Crump' and 'a maid' - in an afternoon play, called Pastoral Symphony, on 24th August 1949. A subsequent audition for TV saw her described by a producer as an 'incredible looking character with bright red hair, dumpy figure and flop nose', and earned her a minor role, once again as a shopkeeper, in an adaptation of John Buchan's The Three Hostages broadcast on 19th July 1952.

Most of her subsequent roles tended to be of the kind of dogged folk who were fighting for their space in the over-crowded urban huddle of Dickensian-style slums. If there was a scene set in a run-down backstreet hostel, or a smoky East End pub, or a noisy and bustling market, it was never a surprise to see her small but aggressive frame force its way into the grime and grind of the action. Indeed, Webb seemed forever rooted in winter, so familiar was her headscarf and furry coat, as if to symbolise the cruelty of the class climate.

By the end of the Fifties she had established herself, alongside Irene Handl and Patricia Hayes, as one of British television's favourite working-class women ('They've only got to see an old mop and a bucket', she said of the programme-makers of the time, 'and they say: "Send for Rita"'). There would be one-off roles in drama series, such as The Wednesday Play, Armchair Theatre, Maigret and Dixon Of Dock Green, along with occasional appearances in such sitcoms as Steptoe And Son, Citizen James and Till Death Us Do Part, as well as plenty of opportunities to play the stooge for the likes of such comedians and comic actors as Fred Emney, Charlie Drake, Dickie Henderson, Ken Dodd, Frankie Howerd, Terry Scott and Jimmy Tarbuck.

Some of her most eye-catching appearances during this period were actually in dramas. In the 1959 play Future Imperfect, for example, she managed, even though she only had a cameo role as a school cook, to steal the whole show as far as the critics were concerned ('those displays of outraged femininity', wrote one, 'mixed up with a smattering of philosophising, created some delightful passages').

She would do much the same in a succession of other parts that demanded varying degrees of dark and dour portrayals. Lacking all vanity, and unafraid to embrace the callousness of some characters, she won plenty of plaudits over these years for her minor but memorable performances.

Her first really significant break, however, came in the realm of comedy when, in 1963, she became a regular member of The Arthur Haynes Show, which, over the course of the next three years, made her an increasingly familiar personality, in her own right, for British viewers. This series showcased her full comic range as a character actor, with sketches that featured her as anyone from a pompous aristocrat to a scrappy servant, with plenty of other types in between, and the importance of her contributions were appreciated by the critics (one of whom described her as 'one of that splendid band of women comic performers whose very presence ensures that there is some outstanding fun in the offing').

The exposure the show extended to her would lead to a few movie roles, including ones in The Idol (1966) starring Jennifer Jones, and To Sir, With Love (1967) with Sidney Poitier (she sat next to him on a number 15 bus, groaning: 'Cor, my bleedin' feet!'). It was on TV, however, that kept her busiest during the next few years.

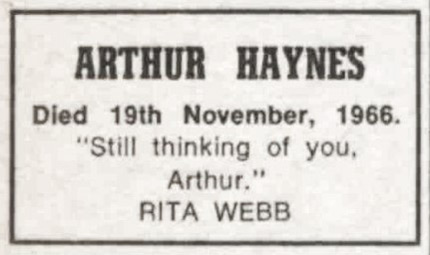

The association with Haynes, with whom she had built up such a warm rapport, only ended with his premature death in 1966 (a loss that left her so saddened that, for several years after, she would mark its anniversary with a memorial message in The Stage newspaper), but Webb continued to be greatly in demand as a player of comedy. Benny Hill wisely added her to his show's list of regular performers, and Frankie Howerd was always eager to find a place for her in his own forthcoming projects.

She was still open, however, to any unusual opportunity that might come her way. She jumped at the chance, for example, to work on an Alfred Hitchcock movie when, in 1972, she was given a very minor (and, ultimately, uncredited) role in Frenzy. Filmed in Henrietta Street, amongst other London locations, she played the mother of the menacing Bob 'Lovely' Rusk (Barry Foster), and only got one line ('Pleased to meet you, I'm sure!'), but she did manage to spend time with Hitchcock himself, which, as far as she was concerned, made the whole experience worthwhile.

She also relished working with another distinguished director, Ken Russell, on Dance Of The Seven Veils (1970), a decidedly unconventional but sometimes inspired film about the life and work of the composer Richard Strauss, made for the BBC's arts series Omnibus, in which Webb appeared as a non-dancing Salome. Hugely controversial - the BBC itself felt compelled to warn viewers via a nervous-sounding announcer that the programme contained 'scenes of considerable violence and horror' - Webb, whose scenes saw her fondled by John the Baptist, declared herself very pleased to have taken part: 'It's bleedin' art, innit, darlin'!'

That was how she found satisfaction in her work. There were plenty of run-of-the-mill engagements, interrupted occasionally by the odd off-the-wall diversion: 'Bread-and-butter with a bit of jam'.

Her private life, meanwhile, was somewhat unconventional, but ultimately very contented. She had married Lionel Stanley Thompson, whom she always called 'Thommie', in 1926 (mainly, it seems, as the quickest means of getting away from the family home), but the relationship didn't last. Seven years her senior, he was a pharmacist, with little interest in the world of show business, and he and Rita soon drifted apart - so much so, in fact, that she lost all contact with him, and would spend many years not knowing whether he was alive or dead.

Although, therefore, she would claim in subsequent interviews that they had ended up getting divorced, they never actually did (indeed, the prospect of the messy nature of her marital status being made public appears to have been the main reason, many years later, why she refused to take part in an episode of This Is Your Life that was being planned for her). The man she later referred to as her second husband, but who never actually was, was a virtuoso banjo player named Al Jeffery.

Meeting in the late-1930s, at a concert in London, they got off to a frosty start - 'When I first met him', she said, 'I thought he was a silly so-and-so. But he played like a divine God' - but soon warmed to each other through their shared sense of humour, and became a thoroughly devoted couple. She took to calling him 'Jeffie', and he started calling her 'Podge'.

He played for a while with the Black and White Minstrels, as well as toured the halls as one half of a double act with Ted Andrews (calling themselves The Jeffery Brothers), before becoming, in later life, a music teacher at Hendon-Ealing Technical School, as well as Rita's unofficial chauffeur. She was so content in his company that she passed on numerous lucrative projects when they clashed with the five-week fishing holiday that she spent with him every year (setting off each time 'holding hands and singing songs in the car').

'When I first got married', she said when interviewed in the Seventies, twisting the truth a little as she tried to explain the nature of their relationship, 'I said to Jeffie: "If you ever want to go, darling, you can. This ring isn't a piece of rope around your neck". You've got to be grateful for what you've had. He's never gone, probably because he could have done so. We still fall into each other's arms as though we were twenty. Mind you, he's got a fat tum and I've got a fat everything, so that's a bit difficult'.

'The other week', she recalled, 'he came up to me in the kitchen for a cuddle. He said, "Oh Podge, let's cuddle while we can". I burst into tears, turned off the stove and cuddled him'. 'I've got the loveliest husband in the whole wide world,' she insisted, 'and that's a fact'.

Jeffie, in turn, was very protective of his partner, even though she protested that she never needed any protecting. When he once got upset to see a script she had been sent, on which someone had scribbled next to a character's name, 'An incredible old hag - we suggest Rita Webb for the part', she assured him that she wasn't at all offended: 'If they want to say I'm fat and ugly, and keep me in work - then I'm fat and ugly!'

The only sadness that they shared was due to their lack of children. 'I couldn't have them', she would explain, 'and it was a terrible disappointment because we both love them so much. But I've got seven nephews and nieces so it's almost as good as having our own family'.

Their home was often full of friends who were sleeping over on their way to or from acting engagements, while Rita made large piles of sandwiches, and opened multiple boxes of chocolates, and Al played away on his banjo. The folk singer Ewan MacColl was a frequent guest in their kitchen, singing along to a shared repertoire of songs until Rita, albeit reluctantly, called the concert to a close ('Be quiet tonight', she whispered on one such occasion, 'Diana Dors is asleep upstairs, she has to be up at six because she's filming').

Her profession, she said, was a fortunate match of passion with pragmatism. 'I'm just a working girl in the theatre because I love it', she explained. 'If I didn't work I couldn't bloody well eat!'

Protesting that she hadn't 'got time for all that slosh', she seldom attended glamorous show business events - preferring, when she could be bothered to leave home at all, to support local good causes, such as various charitable projects for children, animals or the elderly (opening the Paddington Scout Group Bazaar was more her cup of tea) - and was cynical about all the regalia of fame. Signing her replies to fan letters self-mockingly as 'Dame Rita Webb', she had no time at all for pretentiousness, either from herself or from others, and was noisy in noting its unwelcome presence. Brushing aside any praise for her acting talents ('There are millions of raving beauties in the world', she once said, 'but a strictly limited number of old hags like me'), she much preferred to put herself down with a self-deprecating anecdote (such as the time she stepped off a bus and someone shouted, 'I've seen you on the telly. You always remind me of my mother-in-law. She's an ugly old cow - just like you!' - 'I think', she reflected, 'he meant it as a compliment').

Not everyone was drawn to her unvarnished charm. Deryck Guyler was one of those performers who dreaded being in the same production as her. A quiet and very religious man, who often spent his spare time during rehearsals studying the Bible, he was always deeply upset by her blasts of bad language, wincing with discomfort as her voice shook the walls with a steady flow of f-words and worse.

Sir Ralph Richardson was another who appeared somewhat bewildered by her brusqueness. One lunchtime in the canteen at Manchester's Granada studios, where he was filming a classical drama, he stood for so long, trance-like, gazing at the cream-topped desserts that were on show behind the glass that he was unaware of the long queue that had been forming behind him - until, that is, an unmistakeable voice shocked him back into life: ''Ere - yer knightship: MOVE YER BLEEDIN' ARSE!!!'.

She could also, being an inveterate scene-stealer, clash with anyone else who was similarly crafty in the dark arts of catching the camera. 'You fahkkin' little cahnnt!' she would sometimes shriek on the set. 'You fahkked me fahkkin' close-up!'.

Most people, however, saw through the carapace of coarseness and treasured the kind and generous soul inside. Always quick to care for the waifs and strays who came her way, and with a keen eye for the under-appreciated, she was well-known in the BBC Club for insisting on bringing in those studio operatives usually left behind to join in the post-show celebrations ('Out of the way', she would shout, dragging behind her some or other nervous-looking member of staff. 'I want to buy my friend a bleeding drink!'). She also never hesitated to help would-be performers to take their first step into show business (when, for example, she bumped into the fifteen-year-old Lynne Frederick - the future wife of Peter Sellers - at a TV studio, and heard how much she wanted to act, Webb took her to a top agent and helped get her cast in a movie, No Blade Of Grass, directed by Cornel Wilde).

Another young hopeful who attracted her attention was Russell Grant, later better-known for his astrological activities but in those days toiling away as a jobbing actor. He was working at the time for London Weekend Television on the sitcom On The Buses, when, at the end of a hard day's filming, he went off to the canteen at Wembley Park Studios only to realise, as he queued up to pay for his tray, that his wallet had gone missing.

Stammering his explanation to a frowning cashier at the checkout, he was suddenly interrupted by a loud London voice that announced: 'Don't worry, ducks, I'll pay for this!'. It was merely the first of several acts of kindness for him and his friends that Grant would never forget from a woman 'whose heart and warmth was more beautiful than any of your so-called Venuses swanning around the TV studios'.

Even the odd individual who incurred her ire seemed to be charmed by the chiding. On one occasion, for example, she was doing a night shoot on location at a very posh house in London when, between takes, the director informed her that the son of 'Her Ladyship' wished to meet her. 'Charmed, I'm sure', said Webb, holding out her hand to the young man. 'Good to meet you again', he replied with a smile. 'Oh, I don't think I've had the pleasure', she said. 'Oh yes', he grinned, 'the other day, in Leicester Square, you wound down your window and called me a cunt'.

From 1973 onwards Webb did without an agent and managed her career herself from her home at Chepstow Road in Bayswater, which was probably not the wisest move she ever made. The chutzpah would always be amusing ('Hello', she would say - or rather shout - to prospective employers, 'this is not just the best actress in London calling you, not the best actress in the country, but in the whole world!!!') but it did not always win her the best wage, nor, indeed, the best jobs.

Her own pet project, a proposed series in which she would teach other working-class women how to manage their husbands ('If you know anything about men you must study them and you can get all your own way'), came to naught, and she soon found herself floundering around accepting some decidedly uninspiring invitations, such as an awkward co-presenting role in the short-lived ITV health and fitness series Keep Britain Slim (1975), as well as a few cash-driven cameos, such as the painfully shambolic 'erotic' comedy Confessions Of A Pop Performer (also 1975) in which she played a concerned mother (sensibly head-scarfed, of course, and woolly-coated, as usual) searching for her rebellious daughter.

The highs, in these later years, would include some semi-regular appearances in Sykes (1973-5), Spike Milligan's Q6 (1975-9) and The Ken Dodd Laughter Show (1979). She was also a member of the cast (alongside Kenneth Williams, Patrick Newell, Sheila White and Arthur Mullard) for Southern TV's six-part children's series Whizzkids Guide (1981) - a light-hearted on-screen survival manual in which the adults played the schoolkids (Peter Eldin, who conceived and wrote the show, would later recall her modesty - 'After every scene in which Rita appeared she would come straight over to me for approval and ask, "Was that alright, darlin'?"' - and also her thoughtfulness - 'She insisted on taking one of my children's books with her for one scene so it would be seen on screen').

The lows, of this period, would include a bit part in a softcore sex movie full of bits entitled Come Play With Me (1977); kept mercifully away from the flesh-flaunting scenes, she played a Romany fortune teller, Madame Rita, and was merely obliged to compete with a parrot, or at least the sound effect of a parrot, that kept squawking over her lines. She also featured in the movie short Can I Come Too? (1979), which was a sort of X-rated meta-sex comedy, usually shown as part of a dirty raincoat-friendly double-bill with Behind Convent Walls.

She did not seem to mind that, at a time when her acting talent was so well-suited to being challenged with more substantial roles, she was, more often than not, being limited to tiny, under-written, parts in substandard fare (with her annual advert in the actors' directory, Spotlight, taking on a distinctly take-it-or-leave-it tone: 'If you don't know me, you must be a native of another land, whereupon I will come and see you, should you so desire'). She appeared to be happy enough having more hours in each day to share with her beloved 'Jeffie'.

They spent plenty of time together, during these later days, doing nothing much except lapping up the life that went by, and treasuring the pleasure they shared. She knew what most mattered to her, and family was far more precious than fame or fortune.

She still, nonetheless, kept working more or less right up to the end. If there was a chat show, a panel game or an 'in-and-out' acting job, she would take the invitation and put in a performance, showing all of her usual positive spirit even though, in private, she was starting to struggle with her health. Some of her colleagues on the Whizzkids Guide set had sensed her discomfort and asked her if she was unwell, but she had just waved them away with her usual cheerful cackle and carried on with completing her scenes.

One of her last appearances, at the start of May 1981, was on the BBC talk show Saturday Night At The Mill, in which she shared the spotlight with Quentin Crisp. It was an inspired combination, with two profoundly decent individuals who had risen above all kinds of personalised attacks to win the applause that they deserved, and, immediately, they relaxed and enjoyed each other's company, appreciating that they were kindred spirits.

With her health now declining rapidly, 'Jeffie' finally persuaded her to get help. She was admitted to The Samaritan Hospital for Women, in Westminster, on 9th August, where she was diagnosed as suffering from cancer. She would spend her last few days there, still shouting, still swearing, and still making those around her laugh.

Rita Webb died on Sunday 30th August 1981, aged seventy-seven. In her will, she left everything to Jeffie: 'My darling companion and lover'.

The newspaper obituaries tended to describe her as 'Britain's best loved old ratbag'. It was, by the dubious standards of the time, a predictable enough form of tribute, although it ignored her own tongue-in-cheek admonition: 'I don't mind people calling me a fat old bleeder, but ratbag is a bit much!'.

A service of remembrance was held for her on 13th October at St. Paul's in Covent Garden. As her friends and fellow actors gathered to celebrate her life and career, there was more laughter than tears as all the funny stories about this force of nature flowed on and on. The service ended with a banjo rendition of Rita's favourite song, Sparrers Can't Sing.

'She never wanted to be a star', said Al Jeffery fondly, and she was certainly always quick to mock any move to make an adoring myth. When asked to explain her popularity, she delighted in putting herself down. 'I make the plainest woman seem beautiful, so she likes me', she said. 'Men see me on the screen and think, gawd, my old woman isn't at all bad-looking compared to that!'.

Our honesty, however, can acknowledge what her modesty always forbid. Rita Webb was a very talented, intelligent and insightful character actor, a distinctive, indefatigable and unforgettable comic presence, a wonderful woman, and a thoroughly kind, funny and admirable human being. She turned negatives into positives, subverted the stereotypes, and played her people, and did her people, proud.

'I've been bleedin' lucky', she once said. So, thanks to her, were we.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more