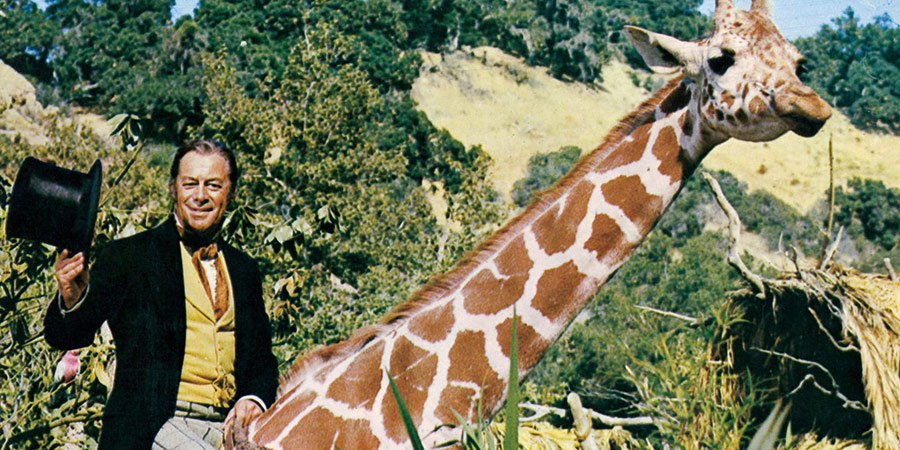

Rex Harrison: His greatest hits

If ever there needs to be a book about the off-screen life of Sir Rex Harrison, then arguably the most appropriate title for it should be: ...And Then I Hit Him. The reason for this is that, if one reflects on all the stories that others have told about him, a remarkably high number of them end up in much the same way, with the words: '...And then I hit him'.

Sir Rex had that effect on people. As an actor, he was one of the truly great players of sophisticated high comedy (much colder and more limited than Cary Grant or David Niven, but nonetheless exceptionally compelling in his playing of certain humorously misanthropic types), but, as a person, he was more than capable of starting a fight in an empty room ('I don't have heart attacks,' he once said in a rare moment of self-awareness. 'I give them to other people'). Co-stars, fellow celebrities, wives, critics, acquaintances and complete strangers - he had the unhappy knack of making an extraordinarily high proportion of them all want to smack him in the face.

How did he do it? The answer to that is easy. He did it because he was, on far too many occasions, arrogant, insensitive, aggressive, ungrateful, rude, boorish, bigoted, tactless, cruel and outrageously self-obsessed.

Why did he do it? The answer to that is perhaps too complex to fathom fully.

Some biographers have speculated that it might have had something to do with a misguided desire to hide his relatively humble Huyton upbringing, modelling himself on the kind of snobbish people who would have treated his younger self with contempt. It did not help, in this sense, that although Huyton, at the time of his birth in 1908, had been a village in Lancashire (which was just about tolerable for someone so class-conscious), it had since been swallowed up by the neighbouring city of Liverpool, rendering Rex, much to his irritation, a sort of born-again Scouser.

Some biographers have pondered the possibility that the near-constant strain on him to appear to be something that he was not - the suave and self-assured leading man - was at the root of the problem. Harrison, due to a severe dose of measles when he was a boy, was practically blind in his left eye; he had started balding as a young adult and thus had to wear a hairpiece throughout his career; and he was also a lifelong hypochondriac who was forever scared of contracting a host of potential health problems. In public, however, he needed to hide how far short he felt he fell below the standards of his glossy on-screen image, and the struggle to do so made him snap and snarl his way through far too many moments.

Other commentators have speculated that his aggressively alpha male attitude could have been prompted by an aversion to (or at least an anxiety about) the idea of homosexuality that was so strong it caused him to act as though he was overdosing on testosterone. He did, late on his career, play a bisexual character (in Staircase, 1969), but even then, according to one of his sons, he procrastinated for such a long time before committing because of fears 'of what the part might force out of him,' and one critic observed of his eventual performance that the role seemed 'to scare him stiff'.

One or two other students of his life and career simply concluded that he must have been born angry.

What is clear is that, due to the sheer number and types of incidents, Rex Harrison richly deserves a chapter of celebrity infamy all of his own. In a discreetly Wodehousian way, like the fate suffered by the fabulously irascible Sir Roderick Glossop at the hands of Bertie Wooster, he always seemed destined to be the most deserved recipient of a surreptitiously-needled hot water bottle.

Few high-profile comic actors, for example, have contrived to get themselves thumped by someone serving them food. Rex Harrison did - and not once, but twice.

The first incident occurred while he was on tour during the war. It happened one evening when he was served some fish in a smart little hotel in Nottingham. Harrison, as a self-made snob, was an obsessive sniffer of food - he even used to sniff the bread rolls - and so, as usual, he picked up his plate, moved it just below his nose, sniffed the fish several times, and then deemed it less than fresh.

This might have caused some diners to seek a quiet word with their waiter. In the case of Rex Harrison, however, it sparked a spectacular tantrum.

It did not matter to Harrison that the threat of German U-boats had rendered fishing hazardous around Britain's shores during those dark and dangerous times, and hindered regular deliveries. It did not matter to him that most food, in wartime, was scarce, and all the public were having to make the best of whatever they could get. The only thing that mattered to Harrison was the fact that his fish, the particular fish that he had expressly requested, had clearly not been caught that morning, and so, in a sudden and raucous rage, he summoned over the maître d'hôtel and barked out his displeasure.

'This fish is off,' he announced loudly. 'Take it away!' The maître d'hôtel, an Italian from the fishing port of Bari who happened to know a great deal about the subject, stood his ground: 'Is all right!' Furious at being challenged, Harrison then demanded to see the chef. 'Is too busy to come out,' snapped the maître d'hôtel. 'This is intolerable!' Harrison exclaimed. 'Bring me the manager!' The maître d'hôtel folded his arms and shook his head: 'Is gone home'.

This was too much for Harrison, who banged his fist on the table and hurled the offending item across and over the edge of the table, smashing the plate on the floor and sending the fish sliding towards the neat little feet of an elderly woman who was dining on her own nearby. The horrified maître d'hôtel responded to this by smacking the actor hard across the face. Harrison - as usual, completely incredulous as to why his action had been questioned - bellowed back: 'How dare you, you fucking Italian!' This earned him the attention of several nearby waiters, and an abrupt ejection from the premises - an action accompanied by loud applause from the other diners.

The second occasion took place a year or so later at another provincial hotel. A permanently sniffing and scowling Harrison was having lunch in the restaurant, and nothing the young waiter did seemed to please his famous guest, who proceeded to shout at and humiliate him from the serving of the entrée to the delivery of the dessert.

Finally, when the lunch was over, the waiter returned to the table and said, 'Oh, forgive me, sir, but there's something under your chair'. Harrison, irritated as usual, sprang up to look, whereupon the waiter leaned back on his heels, raised his right fist, rocked forwards and hit the star so hard that he ended up flat on the floor with blood gushing from his mouth.

'If it's the last thing I do on Earth,' he lisped from a horizontal position, 'I'll have you fired from this hotel, and any other hotel in the country!' 'You can do what you like,' said the waiter with a shrug. 'I'm going to enlist in the Army this afternoon, so it won't do you much good!'

Lilli Palmer, his put-upon wife of the time (the second of six), was there to witness it all. She would later say that it was the best day of her life.

He could be just as unpleasant and bad-mannered when being served within the confines and comfort of his own well-appointed homes. Always affecting an air of Edwardian grandeur, he employed a succession of blue-chip butlers, only to alienate each one of them with his boorish behaviour, and was so obnoxious to one of them that the man ended up threatening his employer with a shotgun.

The dining experience was seldom an occasion to assuage his fiery temper. There was always something that was not quite right - and finding out that something was 'not quite right' was more than enough to send his mood hurtling over the darkest emotional cliff. His fifth wife, Elizabeth Rees-Williams, once said of her preternaturally irascible husband, 'He was the only man I ever knew who would send back the wine at his own dinner table'.

An obsessive cork sniffer in restaurants when the bottles - especially those containing his favourite premier cru white burgundies - arrived at his table, he drove several wine waiters to distraction, pronouncing each vintage proffered as 'insufficiently burnished by the sun' or from 'the wrong side of the vineyard,' or else, after prolonged slurping and slooshing, shouting out the phrase that they most expected but most dreaded: 'Christ - the bugger's corked!'

International success only seemed to make Rex Harrison even tetchier and even more prone to ridiculous tantrums and irrationally tactless acts. In the late 1950s, for example, when he was surfing a new wave of fame on Broadway for his portrayal of the suitably short-tempered Henry Higgins in the musical My Fair Lady, it was a common sight to see the star, post-performance, embroiled in an ugly scene on the pavement with a freshly-insulted former fan.

On one such night, an elderly fur-wrapped woman, who had been standing alone in the rain outside the stage door for the best part of an hour, made the mistake of asking Harrison for his autograph. Rex, impatient to rush off to his next row at a restaurant, told her to 'sod off' and went to walk past to his smart chauffeur-driven car. This so enraged the woman that she promptly rolled up her programme and hit him with it, not once but repeatedly, hard on the head and shoulders, much to the amusement of his co-star, Stanley Holloway, who had just emerged from inside the theatre. Holloway later declared that it was a rare but welcome case of the 'fan hitting the shit'.

Harrison was much the same with his co-stars. His initial reaction to Julie Andrews, who was playing opposite him as Eliza Doolittle, was to bark at their director: 'If that bitch is still here on Monday, I'm quitting the show!' He was just as cold and aggressive to Audrey Hepburn (or 'Bloody Audrey' as he tended to refer to her) when she replaced Andrews in the movie version of the musical: believing her to have been badly miscast, he proceeded to remind her of his opinion throughout the production (which was more than a little ungracious seeing as he would not have been in the movie himself had Cary Grant not turned down the part).

Then there were the 'foreigners'. Foreigners were always likely to arouse Harrison's ire simply because of their existence, to him, as 'foreigners'. When, for example, he decided to spend a period of his life as a tax exile in Portofino (which, with typical cultural insularity, he would claim to have 'discovered'), he only bothered to learn one word of Italian, and his choice - 'buffone!' - was an ominous sign of the troubles he expected to come. Fights breaking out between him and Italian waiters would become a frequent feature of his time there. 'I've lived in this country for fifteen years,' he exclaimed after yet another noisy but mutually incomprehensible public contretemps, 'you'd have thought the little buggers would have learnt to speak English by now!'

The worst incident occurred in 1962 at Rome's Fiumicino airport, where, Rex being Rex, he flatly refused to unpack his bags when ordered to do so by an extremely short but very officious customs officer. As their voices grew louder and louder, Harrison, towering over his opponent, eventually snapped, 'And take your hat off when you're talking to me, you pompous buffoono!' The customs department promptly made a formal complaint against him, sparking an alarming diplomatic controversy of international proportions, as the Italians subsequently maintained that Harrison, by insulting an officer in uniform, had also deliberately insulted the Italian flag.

Such an offence, under the Italian penal code of the time, carried a penalty on conviction of between six months to two years imprisonment, and so the problem was only settled after Harrison was pressured at length into making a full and formal apology to the officer, the Italian president and the entire Italian nation. It was as if a whole country was now slapping Rex Harrison in the face.

He eventually tired of residing in Portofino after the complete breakdown of domestic relationships with his Italian staff, clashes with a local Communist mayor, random illegally-rigged road blocks, an act of sabotage to his Jeep and, last but by no means least, a bungled attempt by his disaffected former gardener to shoot him. 'You've no idea,' his current wife had screamed at him during one of their recent ugly squabbles inside their beautiful villa, 'how the people hate you! They haaaate you!' It had taken twenty-five years, but the message finally got through.

It was much the same, however, whenever Harrison was in France. French people irritated him even more than did the Italians.

Based in a glamorous mansion on Cap Ferrat, he soon managed to alienate his chauffeur, who took to deliberately ignoring his calls, and most of his cooks and cleaners, who quit at an increasingly rapid rate. Venturing out and about to sample the finest of the local cuisine, his usual sniffing and slooshing and spitting out of wine enraged a succession of high-nosed sommeliers, who regarded him as an insufferable fraud, and, yet again, thanks to his noisy insistence that he was a better judge of French food than most of the French, he made himself thoroughly unwelcome in some of the best-rated restaurants in the area.

He once tried to express his anger - as usual at a volume that would have had ears bleeding in the back row of the Old Vic - when he judged that his fillet steak had been cooked for a few seconds too long in a glamorous restaurant in Nice. 'Ce bifstek est brûlé comme la buggère!' he boomed while banging his fist on the table, thus provoking, as the furious chef came hurtling out of the kitchen, yet another sudden punch.

It was not just ordinary members of the public, British or otherwise, who found themselves being provoked into admonishing the star for his rudeness. He had just the same effect on some of his fellow actors.

Charlton Heston, for example, described him as 'a kind of thorny guy,' while Maureen O'Hara called him 'rude, vulgar and arrogant,' Julie Harris declared that she had 'never met anyone who was so self-centred,' Dirk Bogarde said that 'he was always very rude to everybody,' Roger Moore found him 'mean-spirited,' Patrick Macnee judged him 'one of the top five most unpleasant men you've ever met,' and Stewart Granger (who once grabbed him by the throat and threatened to break his 'fucking leg') called him 'a rotten shit of the first water'. Claudette Colbert, when she worked with him, was so desperate to block out his black-hole egotism that she only spoke off-stage in French just to frustrate him.

An all-inclusive irritant, he could be equally rude to his peers as he could be to the young pretenders. While the up-and-coming American actor Frank Langella, on a visit backstage, was crushed to find that his long, trembling and heart-felt expression of admiration to his hero elicited only a curt 'Thank you. Very kind. I'm afraid I can't ask you to sit down,' Sir Laurence Olivier, upon inviting Rex to play opposite him in The Dance of Death, received the even worse brusque retort, 'Only on your grave, old boy.'

He was also predictably difficult and dismissive to most of those people who worked hard behind the scenes, but they had their own crafty ways of exacting revenge, and Harrison would often be plagued by petty thefts, pricked by pins 'mistakenly' left in his costumes, and driven to distraction by the many mysterious malfunctions of his dressing room heating system.

It did not help that he was often so stunningly ungrateful. On one occasion, for example, the eminent Hollywood director, Joe Mankiewicz, had to go to extraordinary lengths in order to persuade his sceptical studio bosses that Harrison deserved to be cast in the forthcoming epic Cleopatra, but his efforts failed to impress his old friend. 'Rex, I've got you the part,' the director exclaimed triumphantly down the phone. 'The part of Julius Caesar is yours. But, to be honest, I truly had to fight for it. The studios came up with all sorts of names, but I held out, and finally I told them to f--k themselves, and that if they wouldn't accept you in the part, they should start finding themselves a new director. I put myself on the line for you, Rex, old boy, and they finally gave in. Isn't that great news? See you in Rome, old boy!' Harrison, who was taking the call while in the company of his agent, Laurie Evans, thanked him coolly, then replaced the receiver and said, 'You know, Lol, I'm wondering if Joe Mankiewicz is the right director for Cleopatra.'

It also failed to help that, even by the standards of leading men, he was astoundingly self-absorbed. He sulked throughout the making of The Agony and the Ecstasy, for example, because, although he had been cast as the Pope, the movie, much to his horror, 'turned out to be some sort of melodrama about a roof-painter!'

Other actors were there to be elbowed out of the way. After sharing a scene with one colleague, he observed that they were having to share the same lighting. 'That's what I thought,' said the other actor, 'I got the impression that there was only one key-light on us'. Harrison's response was very much to the point: 'Then for Christ's sake get out of it!'

Criticism was something he gave but never took. One young female co-star, for example, in a naïve attempt to help, suggested another way of delivering a line that, in her view, he was getting slightly wrong. He merely stared at her, smiled the weakest of smiles and then replied sarcastically: 'Mmmmm, how very interesting to be given advice from quite the worst actress on the English stage.'

He was not always like this. There were times when he could be delightfully bright and witty and welcoming. Sadly, alas, most of the times he was just like this.

The usual pattern for any production - stage or screen - that starred Harrison was a cold and distant start, as far as his relationships with the rest of the company were concerned, followed by a rapid descent into angry clashes, expletive-driven outbursts, endless complaints and simmering resentment. When, late on during one theatrical run, it was noted that his birthday was imminent, one of his co-stars suggested that they should throw a party for all of his friends: 'I'll even hire the telephone booth,' he added acidly.

Finally, there was family, and more of the same old problems: rudeness, bad-temperedness and casual cruelty. His eldest son Noel, for example, once asked him if he would come to watch him perform in cabaret. 'Oh, no,' said Rex, making no attempt to hide his alarm. 'I couldn't possibly do that. It would be frightfully boring for me.' He did once write a letter to his younger son Carey, at his boarding school, but, as it was posted several months after the boy had left, the gesture fell rather flat. Even on his deathbed, when both sons sat by his side, he was as irascible as ever: 'Is there anything I can do for you, Dad?' one of them asked. 'Yes,' he croaked. 'I'll tell you what you can do. You can drop dead!'

Not even the six wives of Rex Harrison could always tolerate his tantrums. He would indeed sometimes receive a sharp slap from one or another of them for something he had said or done.

It was understandable. He was so rarely faithful, often conducting multiple clandestine affairs simultaneously, that he developed the unfortunate habit, at the height of intimacy, of calling out the wrong woman's name. Once he had been through his first few marriages, there was the additional danger of forgetting to whom he was currently wedded. 'Come back, come back,' he cried out as one of them defied him by marching off in a huff, but then he hesitated, realising that he was not entirely sure which wife he had insulted, and continued: 'Come back...You!'

He was also far too self-absorbed to think of any woman as existing for anything other than his own comfort and pleasure - or irritation. On one occasion, for example, he telephoned his current lover at her London apartment when he was at Paris airport en route to another film set, only to hear her exclaim that she was in the process of being burgled. He interrupted her impatiently to say: 'You see, there's this plane to catch, and all these frightful little buggers are all lined up and shouting away. I can't understand a bloody word they say - and I don't have the faintest idea what to do about it. I'll call you when I get to Rome. Goodbye.' The following morning, as she was still recovering from the ordeal, he called her again: 'I'm so sorry about yesterday,' he said, 'but I've just been reading in the English newspapers all about your flat being burgled. I say - I had absolutely no idea I'd bought you so much expensive jewellery...'

He had a trick to appease the most important of the women he had angered: he would send each one an identical letter of apology, allowing him to husband his energies effectively by merely typing in a different name at the top of the page. The ruse worked very well for many years until his fifth wife discovered multiple copies in his drawer - and then she hit him.

While the on-screen Rex sometimes, in the right role, had women wondering what fires might flare beneath that frosty exterior, the off-screen Harrison seemed more like a man of unplumbed shallows. When he was finishing his autobiography, with his latest marriage in a predictable state of stress, he summoned his wife of the time to his study and asked her with typical bluntness: 'Are we going to be together when the book is published or aren't we?' When she asked him why the issue was so urgent, he blithely replied that he needed to know in advance whether to dedicate the volume to her or his dog, Homer.

Although Rex Harrison received his physical comeuppance on numerous occasions over the years - he had grown accustomed to a punch in the face - it was only very late on in his life when he finally experienced his first truly excoriating verbal comeuppance. It came from the distinguished director Michael Rudman.

Rudman was directing Rex in what turned out to be his penultimate stage production, The Admirable Crichton, at London's Haymarket Theatre in 1988. One of the actor's most notorious habits was dismissing most people he met as 'cunts' ('What has Rex ever done for England,' his old friend Harold French asked when hearing that Harrison was due to be knighted, 'except live abroad on his illegal income tax and call everybody a cunt?'), and this production was to prove no exception.

After enduring more or less all of his colleagues addressed by the c-word throughout most of the rehearsal period, Rudman finally snapped, apoplectic with rage, when the elderly actor called him by that word, too.

'Don't you call me a cunt, Rex,' he shouted, 'you're the cunt if anyone is, and you've acted like a cunt ever since we started. When you were young, and at your peak, and a great movie star, you could do just about whatever you wanted, and all your life, you've treated people abominably. You treat your fellow actors like shit, you treat the producers like shit, your agent like shit. You have no respect for anybody, and no concern for anybody, other than yourself, your own needs, your own selfish wants. You have no respect for the play you're in, or the audience who pay to see you. And above all, you treat women like shit, just as you've treated your wives, all your life. But now you're old, and you're nearly blind, and nearly bald, and you're vulnerable and you can't remember your lines, and you're no longer a big rich movie star, it's about time you started to treat people a little differently, and stop calling everybody who stands in your way a cunt, because if anyone's a cunt round here, it's you!'

With that, Rudman turned his back and departed, slamming the door loudly behind him so hard it seemed to shake the building, and a distinctly pale-faced Rex Harrison stood impassively and thought for a moment, and then muttered, 'I think, perhaps, I might have gone a little too far over the top...'

None of this, of course, should diminish our appreciation of the body of work that he left behind on the screen, but it might, perhaps, help us to understand it, and its effect on us, a little better. It might in particular explain, at least to some extent, why - for all of his considerable technical precision and polish - Rex Harrison often seemed so cold and constrained in his performances: because the good actors do not so much hide themselves in a character as they reveal what is most pertinent, in the circumstances, in their own personalities.

Rex Harrison, in life, was simply not that much interested in anyone other than Rex Harrison, and that obviously limited his range of resources when it came to shaping a role for the screen (as John Ruskin once wrote: 'A man wrapped up in himself makes a very small parcel'). He could be brilliant when the characterisation called most of all for anger and acerbity - as is evident in his portrayal of the neurotically insecure husband in Preston Sturges's classic black comedy Unfaithfully Yours (1948) - or superficiality and solipsism - as one can see in his performance as the aimless playboy in Launder and Gilliat's The Rake's Progress (1945) - but he was never anywhere near as effective when called on to convey warmth, sympathy, playfulness or vulnerability. There was always something insular about his individuals, as if a circle had been drawn around them, and their limitations, and flaws, were broadly the same as those of the man who played them.

Maybe this is a reason why, of all Britain's most distinguished light comedians, Rex Harrison remains the least loved. When even a critic as discerning and enthusiastic as David Thomson dismisses the actor with merely a grudging acknowledgement of his 'grating charm', it is hard not to conclude that the hardness of Harrison, on the stage and the screen as well as in life, made him a difficult man to genuinely cherish rather than simply but sincerely respect.

It therefore seems rather apt, in the light of all those off-screen incidents, as well as many of those on-screen incarnations, that the memory, and mood, of Sir Rex Harrison now inspires the character of Stewie Griffin, the explosively bad tempered baby, in the television comedy Family Guy. With his irascible spirit now held captive in cartoon form, there is, at long last, all of the humour with none of the harm.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more