The remarkable legacy of Flanders & Swann

Which bona fide comedy double act has had the biggest and broadest influence on British popular culture? The most instinctive answer, for many, will be Morecambe & Wise, simply because of their huge, broad and enduring appeal. Others might nominate Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, for their unparalleled comic invention; or The Two Ronnies, for their mainstream versatility; or French & Saunders, for their inspirational feminism; or Reeves & Mortimer, for their liberating anarchism. None of these guesses, however, is correct. The most influential British double act is, in fact, Flanders & Swann.

Michael Flanders and Donald Swann have had a profound and lasting impact not only on British comedy and music, but also on just about every other major point and place in the panorama of British entertainment over the last sixty years. From Beyond The Fringe to Monty Python; from Oh! What A Lovely War to Spamalot; from the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band to The Duckworth Lewis Method; from Spike Milligan's Milliganimals to Ricky Gervais's Flanimals; from That Was The Week That Was to Mock The Week; from The Beatles, The Kinks and The Who to Ian Dury, Madness and Squeeze; from Joyce Grenfell and Victoria Wood to Tim Minchin and Melinda Hughes - there are significant cultural strands stretching back specifically to the two-man team of Flanders and Swann.

The sad thing is: it's sort of a secret. Flanders and Swann just don't get mentioned much these days. They don't get heard much these days. They don't get shown much these days.

If someone under the age of about forty has any awareness of them at all these days, they probably know of them, indirectly, from the far more recent Armstrong and Miller parodies, which saw two rather posh comedians play two rather posh comedians ('Brabbins and Fyffe'), singing right-wing-sounding songs whilst being laughed at by rather posh-sounding studio audiences.

This is more than a little misleading. Yes, Flanders and Swann, like Armstrong and Miller, were rather posh, but they were left-wing rather than right, and they were laughed at by all kinds of audiences right across the social class scale.

Even more misleading is that Armstrong and Miller's parody suggests that, if such a double act had actually existed, it must have been as 'cancellable' as this pair. The reality, however, is that neither Armstrong and Miller, nor just about anyone else involved in relatively intelligent comedy during the past sixty or so years, would have thrived anywhere near as well nor as widely without the achievements and lingering influence of Flanders and Swann.

What was it about them, therefore, that proved so inspirational? It was a number of special things.

One of them was their unprecedented ability, as satirists, to personalise politics.

In songs such as There's A Hole In My Budget (written in 1953 when Churchill was Prime Minister and Rab Butler his Chancellor, but reprised many times for future incumbents right up to the present day), they revolutionised the way that British entertainers engaged with current affairs, providing critiques that were immediately accessible and understandable to the broad audience, and, in doing so, somehow managed to seem both topical and timeless ('...But where is the money to come from, dear Premier/But where is the money to come from, my dear?/Why, out of your budget, dear Butler, dear Butler/Why, out of your budget, dear Chancellor, my dear/BUT THERE'S A HOLE IN MY BUDGET...'). Their depiction of macro-economic planning, for example, as two Downing Street neighbours chattering anxiously over the garden gate, gave subsequent comedians a new, more human, way to construct their critical commentary (see, for example, Peter Cook's mockery of Harold Macmillan in Beyond The Fringe, and Frankie Howerd's 'kitchen sink' political monologues of the early Sixties).

They were also exceptionally adept at modulating the tone and tenor of their message. On certain occasions, for example, they could be much darker and more direct for dramatic effect. In their song Twenty Tons Of TNT, especially, they provided a sharply memorable take on the issue of nuclear weapons that was all the more powerful coming from such a charmingly urbane comedic source:

I have seen it estimated:

Somewhere between death and birth

There are now three thousand million

People living on this Earth

And the stock-piled mass destruction

Of the Nuclear Powers-That-Be

Equals - for each man or woman - twenty tons of TNT.Every man of every nation

(Twenty tons of TNT)

Shall receive this allocation

Twenty tons of TNT.

Texan, Bantu, Slav or Maori,

Argentine or Singhalee,

Every maiden brings this dowry

Twenty tons of TNT.Not for thirty silver shilling

Twenty tons of TNT

Twenty thousand pounds a killing

Twenty tons of TNT.

Twenty hundred years of teaching,

Give to each his legacy,

Plato, Buddha, Christ or Lenin,

Twenty tons of TNTFather, Mother, Son and Daughter,

Twenty tons of TNT

Give us land and seed and water,

Twenty tons of TNT.

Children have no need of sharing;

At each new nativity

Come the ghostly Magi bearing

Twenty tons of TNTEnds the tale that has no sequel

Twenty tons of TNT

Now in death are all men equal

Twenty tons of TNT.

Teach me how to love my neighbour,

Do to him as he to me;

Share the fruits of all our labour

Twenty tons of TNT.

On other occasions, such as in Slow Train - their response to the imminent closure of many old railway stations because of the Beeching cuts in the early Sixties - they expressed a common sense of bitterness and regret in the form of a delicate and wistful elegy:

...The Sleepers sleep at Audlem and Ambergate

No passenger waits on Chittening platform or Cheslyn Hay

No one departs, no one arrives

From Selby to Goole, from St Erth to St Ives

They've all passed out of our lives

On the Slow Train, on the Slow Train...

Another one of their special qualities was the subtlety of their subversiveness. Performing at a time in Britain when the Lord Chamberlain's pompously paternalistic 'Regulations' still had to be printed and read at the start of every theatrical performance, Swann elegantly ridiculed this antiquated process by setting them, with mock reverence, to music as the trilogy Smoking Is Permitted, The Safety Curtain Must Be Lowered and All Exits Must Be Open - and thus undermined authority from within.

They were just as innovative in the manner that they mined the mundane irritations of everyday life. In such classic musical scenarios as The Gas Man Cometh (which charted the grimly familiar domino effect of routine 'handyman' mishaps), they produced observational humour that was so vivid, true and precise that it still sounds as fresh and as relevant today:

'Twas on a Monday morning the gas man came to call.

The gas tap wouldn't turn - I wasn't getting gas at all.

He tore out all the skirting boards to try and find the main

And I had to call a carpenter to put them back again.Oh, it all makes work for the working man to do.

'Twas on a Tuesday morning the carpenter came round.

He hammered and he chiselled and he said:

'Look what I've found: your joists are full of dry rot

But I'll put them all to rights'...

Then he nailed right through a cable and out went all the lights!Oh, it all makes work for the working man to do.

'Twas on a Wednesday morning the electrician came.

He called me Mr Sanderson, which isn't quite the name.

He couldn't reach the fuse box without standing on the bin

And his foot went through a window so I called the glazier in.Oh, it all makes work for the working man to do.

'Twas on a Thursday morning the glazier came round

With his blow torch and his putty and his merry glazier's song.

He put another pane in - it took no time at all

But I had to get a painter in to come and paint the wall.Oh, it all makes work for the working man to do.

'Twas on a Friday morning the painter made a start.

With undercoats and overcoats he painted every part:

Every nook and every cranny - but I found when he was gone

He'd painted over the gas tap and I couldn't turn it on!Oh, it all makes work for the working man to do.

On Saturday and Sunday they do no work at all;

So 'twas on a Monday morning that the gasman came to call...

They were also the masters of a kind of witty and wry style of self-deprecation that set the tone for post-war and post-colonial English irony.

In A Song Of Patriotic Prejudice, for example, they teased their fellow countrymen and women about their attitude to themselves ('The English are moral, the English are good/And clever and modest and misunderstood') and to their near-neighbours ('The three unfriendly powers') and to all the others ('And all the world over, each nation's the same/They've simply no notion of playing the game/They argue with umpires, they cheer when they've won/And they practice beforehand which ruins the fun!'), and, once again, it sounds as artful and apposite in the era of Brexit (and renascent Scottish nationalism) as it did more than fifty years before.

Then there was the sheer scope and scale of their satire. 'It is quite something,' remarked one critic at the time, 'to be able to have a funny song about baths and a joke about absurd telephone conversations mixed in with a Nerval sonnet, set and sung by Mr Swann, and an unequivocal comment on the absurdity of war, all blended skilfully together in one popular production'.

Flanders once joked that, whereas satire's job 'is to strip off the veneer of comforting illusion and cosy half-truth, our job, as I see it, is to put it back again,' and, bizarrely, some people failed to grasp the satire in his statement. Flanders and Swann were so effective as satirists because they took the bright-bulbed signs down and shifted the spotlight from form to content. While their opponents watched out for a right hook, they struck decisively with the left.

In addition to all of this, they also inspired other British double acts (as well as a new breed of popular songwriters - see, for example, Ray Davies's work on The Kinks' 1966 single Dedicated Follower Of Fashion, which is at its most Flanders-like with the 'right up tight' line, and their 1968 album The Village Green Preservation Society) to embrace and explore their Britishness. Before Flanders and Swann, the typical British double act behaved like an ersatz American double act - Abbott and Costello-style hard and rapid patter, with transatlantic topics sometimes even delivered with a transatlantic twang - but, after Flanders and Swann, the norm was to remain native and engage with one's own environment. It also became common, again thanks in large part to them, for a double act to be more of a relationship than an 'act', with the connection between the two characters being the key thing that keeps the audience close.

Make no mistake, Flanders was capable of brilliance without Swann, as Swann was without Flanders. Sharp and quick-witted, with the structural skills of a newspaper columnist and the sense of daring found only in the finest of comics, Flanders was a masterful anecdotalist, capable of moving seamlessly from a tale about an olive-stuffing fiesta in the Andorran foothills, to a recollection about an altercation with his local council, to a story concerning a disappointed tourist's derisive critique of Stonehenge, and few other lyricists possessed the knowledge and nous to craft such polished and pertinent lines on topics that ranged from cannibalism and the first and second laws of thermodynamics to the jargon of hi-fi and a politically-charged love affair between a honeysuckle and a bindweed.

Swann, similarly, was one of the most gifted and versatile and thoughtful musicians of his generation. His graceful compositions would range in style from Russian to Hellenic, from classical to folk, from church music to agit-prop, and include everything from a Hebrew cantata to a set of peace and protest songs, and, through his friendship with the authors in question, he made C. S. Lewis's Perelandra into an opera, and adapted material from J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord Of The Rings trilogy for the song cycle The Road Goes On Forever (1967).

Together, however, they formed, like all of the most special double acts, something that was even greater than the sum of its parts. Each had a hand on the other's shoulder, the right word in his ear. Each helped the other to find the best in himself, and, by doing so, the best for their union.

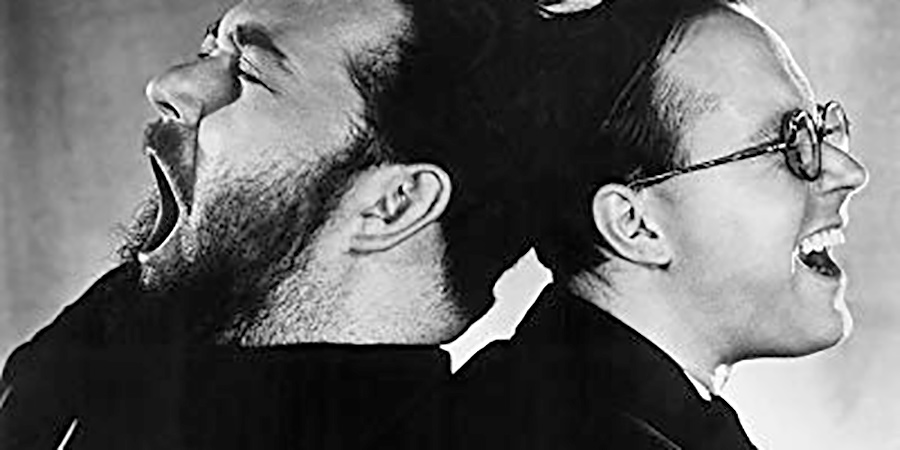

Their shared career was remarkable by any standards at any time. Londoner Michael Flanders, broad and bearded, would dominate proceedings from a wheelchair (a result of the polio he contracted in 1943), while the Welsh-born bespectacled and somewhat bird-like Donald Swann ('the Enid Blyton of light music,' his partner would term him teasingly) would be seated submissively at a grand piano, but together they sparked and spirited each other into action and performed some of the most cultured, witty, worldly and wise songs of the period.

They did not just trap a mood. They also tapped into a soul. They made Britain smile and think when it really needed to do both at the same time.

Both of them products of Westminster School (where their close mutual friend and lifelong fan was Tony Benn) and Oxford (where, besides Benn again, another mutual friend was Kenneth Tynan), they rose rapidly to national stardom in 1957, when their revue At The Drop Of A Hat opened to great acclaim at the Fortune Theatre in Covent Garden. Running for 759 performances, enthusiasts included the Royal Family, almost all of whom were reported to have been heard singing along to Mud, Mud, Glorious Mud (the chorus of The Hippopotamus, one of the pair's most famous songs), on the show's final night of 2nd May 1959.

Although it might now seem - thanks to a mixture of ignorance and presumptuousness - that their appeal was limited predominately to a privileged middle class elite, the reality was that they transcended any class, age, gender, ethnic or regional divisions of the time and, without compromising their craft, genuinely entertained the whole nation, rather than any particular niche. 'There is really no need to introduce Flanders and Swann to the North-East public,' declared the Newcastle Chronicle in 1962. 'They are household words, like fish and chips, tripe and onions, and Tyne and tide.'

When Flanders and Swann homed-in on humbug, hypocrisy and hubris, they spoke for the many, not the few. Take, for example, their refreshingly sardonic response to the risible British annexation of the uninhabitable island of Rockall in 1955:

The fleet set sail for Rockall,

Rockall,

Rockall,

To free the isle of Rockall,

From fear of foreign foe.

We sped across the planet,

To find this lump of granite,

One rather startled gannet;

In fact, we found Rockall.So, praise the brave Bell-bottoms,

Bottoms,

Bottoms,

Who saw Britannia's Peril,

And answered to her call.

Though we're thrown out of Malta,

Though Spain should take Gibraltar,

Why should we flinch or falter,

When England's got Rockall.

They had always, in fact, had too much of an edge to want to be part of the Establishment. Swann, especially, felt as much of an outsider as he looked and sounded an insider; having grown up in a household that was as much Russian and transcaucasian as British, he would later say that he had inherited a keen sense that he was living in a foreign country. Flanders, too, though hailing from a rather less exotic ethnic and cultural mix, was similarly separate from the various orthodoxies of his time, with too restless an intellect to ever be imprisoned within any particular political paradigm.

At The Drop Of A Hat, therefore, offered the kind of intelligence and irreverence that struck a chord and resonated right through the whole country. They were responding to the Fifties, but anticipating the Sixties, and were inspiring all sorts of people as they did so.

Global stardom swiftly followed ('Our songs have made our names a household word,' Flanders observed, 'like "slop bucket"'), with the duo embarking on successive and extensive tours of the show. Still featuring only Flanders and Swann and their single piano - no props, no scenery, no set as such at all ('just two men alone on stage,' as the New York Herald Tribune so aptly put it, 'completely surrounded by talent') - it was the biggest low-key event that many could remember, and no one wanted it to end.

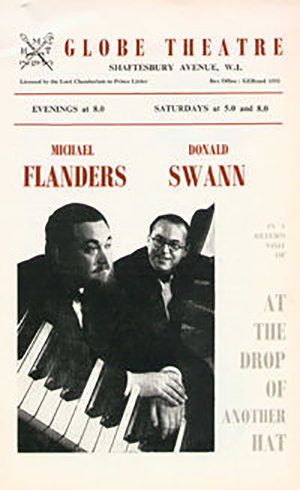

It didn't end. A sequel, At The Drop Of Another Hat, opened in London in 1963, and was then taken on tour in North America, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong. This gave the duo the opportunity to mock not only their native Britain but also many of the other countries around the globe ('You're mad for culture here,' Flanders told an audience in Brisbane. 'Give you a piano and an axe and you'll be happy for hours.' 'Always remember if it hadn't been for the English,' he told an audience in New York, 'you'd all be Spanish'), and they did it in such a charmingly artful way that even those who felt the digs the deepest still laughed and loved them.

The production finally reached a climax with a long run on Broadway during 1966-7 that drew huge audiences and countless pages of praise. One critic enthused that the show was 'as witty as Wilde, as clever as Maugham, as waspish as early Coward and as civilised as any', while the partnership itself was 'as natural, joyous and talented a combination of words and music as was the celebrated team of Gilbert and Sullivan'.

Their achievement was all the more remarkable given the fact that no other British double act had reached very far, if at all, beyond their own domestic audience. Flanders and Swann, in contrast, had now established themselves as an international phenomenon.

Now starring in an era of intelligence, playfulness and irreverence, of Not Only... But Also... and Private Eye, Penny Lane and Arnold Layne, anti-war campaigns and peace protests, smart political satires and artful critiques of suburbia, comic articulacy and musical adventurousness, they must have felt like architects living in a landscape that they had helped design.

Having reached their peak (they were already an institution, but, as Flanders remarked, 'who wants to live in an institution?'), they then parted and went their separate ways, but their critically-acclaimed recordings (most of which were produced by Sir George Martin, who would later claim to be as proud of his association with them as he was of that with The Beatles) would continue to sell in countless countries. Their songs would also inspire numerous tribute shows and performances over the coming decades, ranging from reverential reproductions to affectionate parodies, as well as a wide range of more indirect and intriguing adaptations of their art.

Fashions may since have changed, and some memories faded, but Flanders (who died in 1975) and Swann (who died in 1994) still have many notable admirers today, including, in Britain, John Cleese, Ian Hislop, Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie (and, yes, deep down, Armstrong & Miller as well), and, in America, the Hollywood actor John Lithgow, the singer and Family Guy creator Seth MacFarlane and the Frasier star David Hyde Pierce, all of whom have praised and performed their work. A further sign of their enduring significance within some cultural circles occurred as recently as September 2018, with the unveiling of an English Heritage blue plaque at 1 Scarsdale Villas, Kensington ('turn left by Ponting's dustbins'), in the garden studio where the pair once lived and worked.

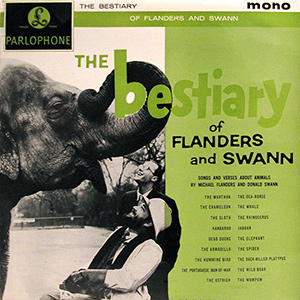

For those, however, who have never known much, if anything, about this remarkable duo, there is some extraordinary material out there just waiting to be explored. In addition to the original albums - At The Drop Of A Hat, At The Drop Of Another Hat and The Bestiary Of Flanders And Swann - there is also an excellent box set, The Complete Flanders And Swann, an illustrated volume of lyrics, The Songs Of Michael Flanders And Donald Swann, as well as a rare live concert video on YouTube. There is also a website run by Leon Berger on behalf of the Donald Swann Estate - donaldswann.co.uk - which contains many invaluable resources relating to the work of both performers.

Listen, when you have the chance, to the words and music of Flanders and Swann and, after a while, all of the extraneous sounds and visions - their 'classness', their 'pastness', their very 'black-and-whiteness' - will begin to float away, and you'll be able to notice, through fresh eyes and ears, each of the roots that have nourished your own favourite branches of popular culture - the musical adventures, the satirical steps, the flights of fancy, the domestic comedies, the political critiques, the dark allegories and high ironies and all of the recognition humour - and, suddenly, on radio, TV, movies, in music and print and even on the internet, the rare genius of these two men will seem, once again, 'ever so very contemporary'. So many strands, from so many traditions, stretch all the way to us, and mean so much to us, courtesy, at least in part, of Flanders and Swann.

This is the double act, more than any other, from out of which so many other artists' dreams have been made. In popular cultural terms, rather like Auden said of Freud, they are no longer people now but rather a part of the patchwork of our thinking. They should never, therefore, be kept a secret, or be obscured by some patronising parody. The rich and varied influence of Flanders and Swann lives on - and so, in a real way, should they.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more