One sitcom did 'ave 'em: The strangely short career of Raymond Allen

The history of sitcoms contains quite a few instances where even the most eminent writers came up with ideas that lacked the legs to work as long-running shows. What is far less common is the opposite: excellent ideas whose writer lacked the legs to keep them running. That, essentially, is the case with the writer who originated Some Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em, Raymond Allen.

Allen was rather like a natural middle-distance runner who kept entering himself for marathons. He started well, then struggled, and ended up having to be helped over the line.

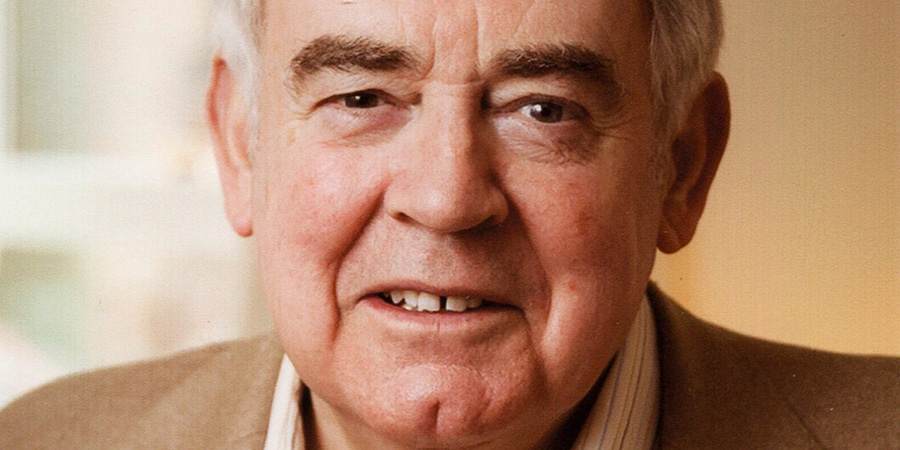

It had nothing to do with hubris. Blessed with a sweet-natured outlook, an endearingly quiet ego and a warm and gentle West Country burr of a voice, Raymond Allen (he was more commonly known as 'Ray,' but used his full name formally to distinguish him from the more famous ventriloquist Ray Alan) was one of the nicest, kindest, most considerate and most self-effacing comedy writers in the business; he was, if anything, far too modest and humble for his own good.

The problems he encountered when writing sitcoms came simply from the fact that he was at his best when drawing from real life experiences, and when he needed to supplement those real-life experiences with invented ones to keep the episodes coming, he struggled more than most.

He did, to be fair, have quite a store of very funny real-life experiences on which to draw, because he had always been the sort of person who seemed to keep stumbling into sitcom-like situations. Always fearful of upsetting other people, and forever ready to fit in with their preferences and schedules, he sometimes found himself, as a consequence, at the centre of comic chaos.

An example was the time, very early on in his adult life, when he was working as a cub reporter for a regional newspaper and was sent to compile an article about the recent death of a local man. Acutely uneasy about intruding into private grief, he hesitated outside the house for some time, wandering up and down a nearby path, before summoning up the courage to knock on the widow's door. 'Come in,' the woman said, surprisingly brightly, when he explained that he had come to write something about her husband.

'She's really bearing up well,' he thought to himself as she insisted on making him a cup of tea. Once she had joined him at the kitchen table to munch on some digestive biscuits, he forced himself to inquire if he could start asking her about her beloved partner. 'Yes, of course,' she replied, 'but I think it's only right that you should see him first.'

Somewhat taken aback, but ready to respect her wishes, Allen asked where he was. 'I've left him in the front room,' she replied matter-of-factly. 'If you go down the hallway you can't miss him.'

Now considerably more than a little uncomfortable, Allen nodded sympathetically and made his way nervously through to the designated resting place, where he found the husband, dressed only in trousers and vest, laid out on a couch with one shoe on and the other one off and a newspaper hanging over his head. It was a few seconds later, as Allen stood there aghast at such apparent disrespect for the recently-deceased, that he suddenly noticed that the newspaper was rising and falling, and then, even more abruptly, the man bent forward and belched.

Terrified, the cub reporter ran back to the kitchen and cried out, 'Your husband's just sat up! HE'S ACTUALLY JUST SAT UP!!!' 'Oh, right,' said the wife, completely unfazed. 'You'd better ask him, then, if he wants a cup of tea.'

'But-but,' gasped Allen, 'he's supposed to be DEAD!' 'Oh, no, dear,' replied the wife. 'That would be the man next door.'

Another embarrassing situation took place many years later, when he had holed himself up, alone upstairs at his home on the Isle of Wight, so that he could concentrate on getting some writing done. Hearing a knock at the door, he peered out of a window and saw the flat-capped head down below of an especially boring near-neighbour who, if admitted, was bound to keep him talking for ages. So - never being any good at simply telling someone to go away - Allen hid and waited for the visitor to give up and wander off.

Eventually, after what felt like an eternity, he heard footsteps fading away and the garden gate clanking shut. Relieved, he looked back out of the window and, to his immense frustration, found that the man had stopped and was now standing by the gate looking straight up at him. Greatly embarrassed, he went downstairs and opened the door.

'I'm ever so sorry,' he said with blushing cheeks, 'I'd ask you in but I'm really, really, busy.' The unwelcome visitor, seeing a case in the hallway, replied, 'Oh, are you just going out?' Grateful for any excuse, Allen said that he was indeed just about to go out.

The man then asked if he was off to another one of his regular meetings in London. Allen, again over-eager to accept the cue, replied that he was. 'Okay, then,' said the man cheerfully. 'You'll be going by boat, won't you, so I'll give you a lift to the station'. Allen, cruelly trapped by his kind lie, meekly agreed, put on his coat, picked up what was actually an empty case, and got into the man's car.

Once they arrived at the station, which was only about half a mile away, Allen planned to thank him politely and then walk straight back. His relentlessly nosy neighbour, however, had other ideas.

'What boat are you catching, Ray?' he asked. 'Oh, er, the next one,' Allen replied in the most casual sound he could conjure. 'Right, well then, look,' said the man, 'it's just coming in, so we'll have to hurry - I'd better take you straight down to the pier.'

Now desperate for a way out of this humiliating spiral of lies, Allen decided to adopt a look of alarm and exclaim, 'Oh, no! Oh dear oh dear! - I've forgotten to get my ticket!' Thinking that this had finally extricated him from the situation, he said that he would now be hurrying straight off to the ticket office, and, thanking the man profusely for all of his 'help,' assured him that he was now free to leave and drive back to his own home.

Much to Allen's horror, however, the man ran off and started shouting at a member of the crew on board the boat: 'This gentleman needs to get on your boat - does he still have time to get a ticket?' 'Yes,' came the reply, 'if he's quick!' The next thing that Allen knew, he was being hurried along to the ticket office, where he felt he had no choice but to buy the fare for a return trip, and was then rushed back to the boat, where the neighbour bundled him on board.

Beaming brightly at the execution of his good deed, the neighbour waved to Allen, and Allen (smiling weakly) waved back, as the vessel took him out to sea.

Utterly drained, he ended up back on dry land in Portsmouth, sitting sadly inside the station, his empty case by his side, waiting for the next boat to take him straight back to the Isle of Wight. Once again, his politeness had punished him to a comical extent.

Other incidents included the one where he passed his driving test with flying colours but then spent years resisting buying a car out of nervousness about his own ability, only to finally be persuaded it was high time for some refresher lessons - which saw him drive straight through a hedge and into a ditch (his young instructor was apparently so traumatised that he promptly resigned and joined the Army); another occasion where, mistaken for the manager of a DIY store while he was there trying to buy some grout reviver, he was pursued up and down the aisles by an irate customer demanding compensation for some faulty electrical equipment; and the time when he was flattered to be invited to be the guest of honour at a venue, only to be asked once he got there why he hadn't brought his ventriloquist's dummy Lord Charles.

Perhaps the most farcical episode of all occurred at the start of the Seventies, after Allen had begun to work part-time as a budding comedy writer. Having had a few gags accepted by Frankie Howerd for one of the comedian's (untelevised) cabaret shows, he was thrilled when a message arrived sometime later inviting him to meet the great man with a view to supplying him with more material.

Howerd, as was his wont, was staying at the time at a health farm in Surrey (Grayshott spa near Hindhead), so it was arranged that Allen would travel there, armed with a briefcase full of comic scripts, sketch and sitcom ideas, to see him. Fussing well-meaningly over the writer's route, Howerd sent him detailed instructions as to how best to get there, advising him as to which trains to catch until he got to Haslemere, after which he should go the remainder of the way by taxi.

Allen, however, was slightly worried, as a freelance, about the expense of it all, and so, once he arrived at Haslemere, he decided to travel the rest of the way on foot. Asking a passing postman for directions, he was told, rather brusquely, to walk off down the road. What he wasn't told was that it would take him, even at a brisk pace, the best part of an hour.

What made matters worse was that this was happening right in the middle of an especially cold February (''Tis chilly! Yehss, 'tis!') and it had been snowing. Wrapped up in a thick overcoat, Allen clutched his bulging briefcase and headed off unsteadily into the icy wind, took several wrong turns, tried a short-cut across a field, got chased back the other way by an angry bull, fell in a ditch, slipped over multiple times on the ice, staggered into a rain storm, and then, realising he was by this stage extremely late, forced himself to run the rest of the way.

When he finally arrived at the spa, soaked to the skin and wheezing pathetically, he was well over an hour late and Howerd had given up waiting and gone back up to his room. The receptionist, taking pity on this damp and desperate man, called up the resting comedian and managed to persuade him to welcome the belated guest.

Coughing and gasping as he trudged up several flights of stairs, Allen entered the room to find that Howerd was now sitting up in bed, looking white as a sheet with worry. 'I've been listening to you coming up all those stairs,' he exclaimed, 'and I thought you were having a heart attack - what on earth's the matter with you?'

Once the bedraggled Allen explained how far he'd walked and in such inhospitable conditions, Howerd said, 'You must be MAD! Why didn't you get a taxi??' When his would-be regular writer admitted that he was trying to save money, Howerd became distressed. 'I'm so sorry,' he cried, 'I feel terrible now, I'm really so sorry. I didn't realise you were so poor!'

Allen, after doing his best to reassure the star that he really wasn't anywhere near as impoverished as he seemed to have assumed, managed to calm the situation down and the two men then talked over a few ideas about future stand-up routines. Once an hour or so had passed, however, Howerd slumped back into his pillows, sighed and said, 'Oh, I'm SO bored here in this spa! Once I get out I'm renting a place in the south of France. Would you like to come with me, Ray, hmmm? Don't worry, I know you're hard up - I'll pay for everything!'

A startled Allen, rapidly turning red like a thermometer about to pop, rushed to explain that he was most definitely not gay and would therefore have to decline the kind offer. The two men then looked awkwardly at each other until Allen stuttered his apologies and said that, as it was getting dark, he would have to set off on his return journey.

At this point, Howerd jumped out of bed and began searching through all of his cupboards and drawers trying to find the money for his visitor's taxi fare. Hugely embarrassed, Allen protested again that he really wasn't that poor ('H-H-Honestly, Mr H-H-Howerd, it's all right - er, it was so nice to have met you!') and, panicking, raced out of the room, ran down the hall and promptly tripped over and fell straight down the final flight of stairs, his briefcase bursting open upon impact with the ground floor and sending sample scripts shooting out at all angles across the foyer like snooker balls at the start of a break.

It was here, as he lay in a sweaty and crumpled heap at the bottom of the stairs, that the numerous startled guests who were crowding around him heard a thumping noise from above and looked up to see a harassed-looking Frankie Howerd hovering on the landing, with one hand holding on to his untied pyjama trousers and the other one holding up a crumpled note, shouting: 'Ray! Ray! Will five quid cover it?'

Those kinds of things always seemed to happen to Raymond Allen. It was as though life was leading him towards a career in comedy.

Born in Ryde on the Isle of Wight in 1940, he spent most of his first thirty years being nice and kind but chronically unfulfilled. Leaving school at sixteen, he started work as a reporter for the Isle of Wight Times, but, after realising that he was probably far too respectful of other people's privacy to keep pestering them for stories, he quit after eighteen awkward months.

A three-year spell serving in the RAF followed (he was based in one of its accounts offices in Gloucestershire), after which he resolved to take on undemanding jobs while writing plays in his spare time. The plan was for him to turn professional as soon as his efforts started getting accepted.

The problem was that they didn't start getting accepted. Cut off from England's bustling centres of show business activity, he continued to labour away in lonely isolation on the Isle of Wight, scribbling down ideas by night while he earned a modest living by day, washing the dishes at the Castle Hotel in Ryde before moving on to cleaning the toilets at the Regal Cinema in Shanklin.

Even when he seemed to be on the verge of a breakthrough bad luck always intervened. On one occasion, for example, his standard 'embellishment' of his current lavatory-based occupation whenever he was seeking writing engagements - 'I'm in the film business' - finally appeared to have paid-off when (in response to one of the many speculative messages he sent to the mainland) someone contacted him about working on a screenplay. Not wanting to admit that he did not own a phone of his own, he advised his potential employer (after checking that he was not familiar with anywhere on the Isle of Wight) that the best way to reach him was by calling a grand-sounding place called The Regal where he liked to take his mid-morning tea.

Two days later back in Shanklin, the phone duly rang at the cinema, and the movie man asked if the receptionist would page Mr Raymond Allen for him. The receptionist replied, 'Could you call back in about ten minutes, dear, because, you see, he's just mopping out the Gents at the moment.'

It was another humiliation for the hapless would-be author, whose subsequent attempt to explain away this revelation - by claiming that he was merely seeking some colourful material for a script - failed miserably. 'How long have you been seeking colourful material by cleaning toilets?' exclaimed the man. Allen, his brain now numbed by nerves, had to admit, 'Er, about four-and-a-half years'. The caller replied caustically: 'It must be a hell of a long script'.

Allen never heard from him again. After a number of other people were obliged to contact him via similarly gaffe-prone circumstances, he seldom heard from any of them ever again.

He was still writing plays - mainly serious ones in nature - but, all through the 1960s, the only thing he was acquiring was a pile of rejection slips. 'I remember clearly the day my fortieth drama script was rejected with a note from the TV company's script-reader telling me to write about something I knew,' he later reflected. 'Unfortunately, there wasn't much about life I did know. At nearly thirty, I'd never been abroad, had little money, no proper job and was financially supported by my parents. Not surprisingly, I was very depressed.'

Deciding ('more in desperation than hope') to turn his attention from drama to comedy, he was soon intrigued by the coverage, during the latter half of 1969, of a new BBC sitcom called The Liver Birds - mainly because so many critics were celebrating the fact that, unusually for the time, it starred two women. Hoping that he could fasten on to this new fashion, Allen started working on his own sitcom which would feature a smart woman (based on his own girlfriend of the time) and a stupid husband.

Once he settled into the project, however, he found himself growing more interested in the man than he was in the woman, and so he shifted the focus. Drawing on his own history of embarrassing and sometimes calamitous experiences, as well as his chronic clumsiness and carelessness ('I am accident-prone. I tend to drop trays and break things, and I'm always walking into things that have just been painted'), he realised that he could indeed write about what he knew - himself - and now it was making him laugh.

There was also, in truth, a basic template to which he could refer as he started shaping his first story. It was the long-running Charlie Drake sitcom The Worker, in which the central character - a well-meaning but hopelessly incompetent little man - kept getting jobs, messing them up and infuriating his bosses, before ending up getting sacked. Developing his own version of such a social misfit, far less cunning and creepy than Drake's incarnation, Allen started to fashion a warmer, more vulnerable figure for his fiction (which effectively became 'The Worker and Wife').

The name for this character was certainly called-up from his own memory. There was a man he often used to see back in Shanklin at the Regal. 'When I was outside cleaning the steps of the cinema,' he later explained, 'this strange little local man called Frank Spencer would point to a poster and say "What's that film about? Is there any violence in it?" If I said I thought there was, he would toddle off with his dog mumbling. "My wife wouldn't like that!"'

Slowly but surely, the pieces were being put into place. For the first time in his life, Allen felt as though he was getting somewhere.

Throwing himself into the field of comedy, he not only continued, very slowly, to work on his sitcom (which by this time had acquired the working title of Have A Break, Take A Husband with the couple called Frank and Betty Spencer) but also started writing and sending out gags to as many potentially interested parties of which he could think. Pages were passed on to stand-ups, sketch shows and panel programmes, and most of them came straight back, but, after a year or so, he did start to attract some interest.

Aside from Frankie Howerd, he also managed to get a modest amount of material accepted for use in the BBC One revue show Don't Ask Us - We're New Here (1970) and a couple of raw ideas were developed for an episode on the same channel of Dave Allen At Large in 1971. It was not much, but it was more than enough, after enduring so many disappointments, to encourage him to push on with his comedy projects.

Now able to cite some credits in support of his scriptwriting skills, he sent in the completed pilot episode for his sitcom to Michael Mills, who had only recently stepped down as the BBC's Head of Comedy in order to concentrate on making programmes again himself. Mills, who was not only a seasoned producer but also an award-winning writer, was not particularly impressed, to put it mildly, by the script itself (which featured Frank and Betty as a honeymoon couple in an alarmingly fragile hotel room), but he thought that the basic situation, of the 'normal' woman trying to cope with the strangely likeable buffoon of a man, had excellent potential to become a very funny series.

No one else at the BBC could work out why Mills grew so rapidly committed to the project ('I think most of us looked at the script,' Bill Cotton, Mills's friend and colleague, would later tell me, 'and dismissed it as far too slight, but Michael had an instinct about these things, and when he was sure about something you just trusted him and let him get on with it'), but Allen was ecstatic that finally he had the backing of such a powerful figure. So grateful was he, indeed, that he wasn't at all offended when Mills started sketching out his own ideas for plots, dialogue and characterisations ('They were very good ideas,' Allen later observed), planned a new pilot, came up with the idea for the Morse code theme tune and also - as he usually did - took charge of all the casting.

Allen had envisaged the role of Frank as being played by Norman Wisdom. Mills did not agree - the comic actor was now heading towards his sixties, and therefore was hardly the right age for the part - but, out of courtesy, he did sound him out about the project (although the fact that he sent him Allen's original, underwhelming, pilot script suggests he was angling for a negative reaction). Wisdom turned it down - he liked the character, he said, but was bemused by the lack of much comic dialogue ('Is he putting the funny lines in later?') - and Mills was free to look elsewhere.

Bill Cotton suggested Ronnie Barker, mainly because, aside from admiring him hugely as a performer, he had signed him on a contract that promised him, in addition to his Two Ronnies work, a solo series each year. Barker, however, felt that the role of Frank was too physical for him, and, besides, he was already in the process of developing several potential sitcom ideas of his own.

A number of other actors then passed on the chance of playing Frank - including the Carry On star Jim Dale and the former Herman's Hermits singer Peter Noone - and David Jason was discussed but then dismissed on the grounds that he seemed better-suited to playing 'sidekick' roles. Allen, hearing about every rejection as he raced to complete six more scripts, was starting to fear that his sitcom was never really going to get off the ground.

Michael Mills, however, was still hoping that his own original choice would soon become available: Michael Crawford. 'He'd been to see No Sex Please, We're British,' Bill Cotton would recall, 'and he'd seen Michael Crawford [in the role of the harassed bank clerk Brian Runnicles] and he said, "He is the very one". I remember him saying it to me with absolute conviction: "He is the very, very man who can do this!"'

Crawford, once some other commitments had been completed, would indeed be the man, but he insisted, before signing any contract, that he first needed a private meeting with the author. This would prove to be a more peculiar experience than Allen had expected, because Crawford, as a meticulous planner of characters, wanted to show him, in person and in persona, his own initial take on Frank Spencer.

'It was at his house,' Allen would recall. 'The meeting was at ten in the morning but I later found out he'd been up since four working out exactly how he was going to play Frank. And so when he opened the door, he was dressed like he thought Frank should dress, acting like he thought he should act, walking like he thought he should walk, and talking like he thought he should talk. And I remember looking at him and thinking, "Well, I didn't think he'd be like this!"'

Once the two men sat down in the living room and Crawford, still in character, had served him, rather messily, tea and biscuits, he asked Allen if he had noticed that he was twitching. 'Oh, yes, but I thought you were just nervous,' the writer replied innocently. 'No, no,' exclaimed Crawford impatiently. 'I'm acting!'

He then asked the writer what he thought of his voice. 'Don't you always talk like that?' Allen asked. 'NO!' cried Crawford. 'It's Frank's voice!'

Allen feared he had caused real offence when, after being invited to comment on Crawford's funny way of walking (tummy in, bottom out, knees up, feet shooting out sideways) he confessed to wondering if the actor was suffering from a hip injury. Once the confusions had been overcome, however, they could not have bonded better. 'I thought he was a genius,' Allen would say.

The two men worked together unpaid for the next three months as they further refined each aspect of the show. A particularly accident-prone session at the home of Michael Mills, during which an entire crockery set was dropped and broken, a vacuum cleaner was jammed and a lavatory U-bend was blocked, encouraged them to add more elaborate slapstick scenes into the scripts.

Some Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em finally reached the screen in February 1973. After a very low-key and slow-burn of a beginning, it eventually found a huge audience, and ran for three very successful series and three specials over the course of the next five years (and has since been sold to more than sixty other countries worldwide).

It should have been the start of a long and celebrated sitcom career for Raymond Allen, but, instead, the start was also effectively the end. He just couldn't get another project to progress.

There was a pilot broadcast in 1974 called The Dobson Doughnut - put out as part of the BBC's well-established and high-profile Comedy Playhouse showcase - which co-starred Milo O'Shea (as an eccentric explorer whose plan to sail around the world is sponsored by a local baker) and Jo Kendall (as his long-suffering daughter). It flopped, with one critic complaining that it 'lacked any real identity, coherent style or distinction'.

Two more pilots were made - Don't Move Now in 1976 (a removals firm comedy featuring David Kelly and Brian Glover), and Sidney, You're A Genius in 1977 (starring Matthew Kelly and Maria Aitken and co-written with Jimmy Perry) - but both failed even to reach the screen.

He did have some modest success with a stage play entitled One Of Our Howls Is Missing (a farce set in a hotel, which was written in 1976 but only went into production three years later, touring the provinces during 1979), and also contributed some sketches for the comedian Jimmy Cricket in All Cricket And Wellies (1986), the 1987 children's series Fast Forward, and the 1987 and 1988 runs of The Little And Large Show (he would also provide some dialogue for the one-off Sports Relief revival of Some Mothers in 2016). No further shows of his own, however, would happen.

The main reason was that, as he later admitted himself, he struggled to come up with new ideas, and, when he did get a new idea, he found it even more of a struggle to develop it very far (strangely enough for someone who in casual conversation seemed such an effortlessly entertaining storyteller, he often had problems with plots when he was writing). Right from the start with Some Mothers, Michael Mills and (increasingly so) Michael Crawford had worked on all of Allen's scripts as a team, adding ideas, scenes and dialogue that would sustain the show for the length of each series. When he was back trying to go it alone, however, he simply lacked the creative stamina, and self-belief, to drive on through to the finishing line.

There were no strong feelings of regret. While he would have liked to have done more, he was immensely grateful for what had worked so well.

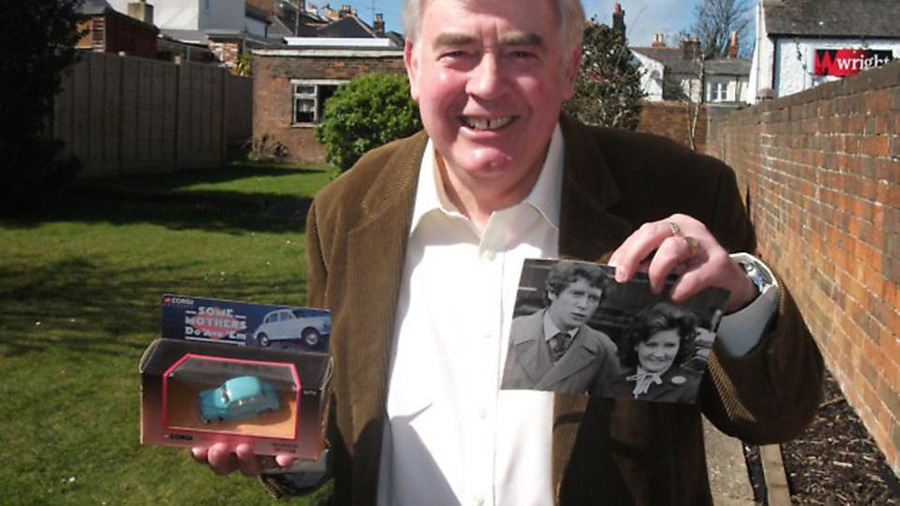

He also never lost his self-deprecating sense of humour, which, given how prone he remained to stumbling into sitcom-style scenarios, was just as well. On one occasion, for example, his agent phoned to say that a company wanted to produce a Morris Minor limited edition, in honour of the famous Some Mothers episode in which one of them dangled over a cliff, and, if they could use the show's name on it, they would give him a free car.

Allen - who was still without his own vehicle - was delighted, and, on the day it was due to arrive, he even went to the trouble of putting some cones outside his house so there would be a space in which to park it. Some hours later, however, there was a knock on the door, a man said he had come to deliver the car, and promptly handed Allen a smartly-packaged Corgi toy. 'It was a bit of a let-down,' he would laugh, 'but I've always kept it.'

When he passed away, aged eighty-two on 2nd October 2022, there was far more coverage than he would have expected, and far more sadness than he would have wanted. Always delightful company, he had lifted other people's spirits all through his life, not just during a short spell on the screen, and that, for all his modesty, was a rare and special achievement.

Michael Crawford, when paying tribute, summed it up rather well: 'Raymond has left us all with wonderful memories filled with fun, laughter and love. He will be remembered as a very humble, kind and generous man. His legacy will live on. He will be greatly missed by many.'

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreSome Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em - The Complete Series Plus Christmas Specials

The complete Series 1-3 plus the three Christmas specials of the 1970s BBC sitcom starring Michael Crawford as the accident-prone Frank Spencer.

Well-meaning and optimistic, but naïve, clueless and spectacularly incompetent, Frank would find situations spiraling hilariously out of control. His long-suffering wife Betty can only stand by and watch as he is catapulted into "a bit of trouble" by the simplest task - a window cleaning job, a driving test, DIY or an RAF reunion. Michael Crawford was renowned for performing his own stunts in the series - some of the biggest and most dangerous in British comedy, including the holiday camp "bluecoat" human fireworks display, hanging from the exhaust of his Morris Minor as it teetered on a cliff edge and an unbelievable extended roller-skate.

First released: Monday 14th February 2011

- Distributor: 2 Entertain

- Region: 2

- Discs: 4

- Catalogue: BBCDVD3287

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.