Random acts of kindness #2: More comedians being nice to each other

As this is at least supposed to be the season of goodwill to all people, a tinselly romantic time in which we can slip contentedly into our hoggish slumbers warmed by thoughts of Jimmy Stewart running through the snowy streets of Bedford Falls, with some precious petals still in his pocket and a guardian angel guiding him back home, it feels like an appropriate moment to remind ourselves of how even hyper-competitive comedians, every now and then, can behave rather like good old George Bailey, and do something genuinely kind and nice for each other.

In an earlier article on this subject, it was noted how Ernie Wise looked after his ailing partner, Eric Morecambe, and how Des O'Connor revived the career of Jack Douglas, and how Douglas, in turn, sought to ease the burden on the desperately sad situation of the Parkinson's-stricken Terry-Thomas. For this piece, happily enough, there are several other examples to add to those anecdotes.

One such instance concerns a man by the memorable name of Issy Bonn. A big, bluff and cordial character, Bonn - whose real name was Benjamin Levin - was a popular music hall comedian and singer, most successful during the 1930s and 40s (but remaining memorable enough to be included, among the many other iconic celebrities pictured, on the cover of The Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album in 1967). His mixture of stories, songs and sketches (he was often billed as 'The Hebrew Vocal Raconteur') was not to everyone's taste - it was inclined, at times, towards the overly-sentimental - but it would continue to command a fairly large and loyal following on radio, records and the stage both during and for some years after the Second World War.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bonn had, from early on in his career, been alert to the need to protect himself financially from the cruel vicissitudes of show business, and invested his earnings wisely enough (amongst his increasingly bulging property portfolio were several large storage facilities for variety and pantomime sets that would prove extremely and enduringly profitable) to be in a position to produce and promote as well as perform. Always philanthropically-inclined, he worked regularly for charities, was well-known for his concern for the under-privileged and was much-admired for the encouragement, advice and support he offered to any up-and-coming entertainer who seemed in need of it.

He had witnessed, many times, how brutal the business could be ('When they pat you on the back,' he sometimes warned the more naïve of the younger performers, 'they're often looking for a soft spot to plant the knife'). He was, as a consequence, determined to demonstrate that there were at least some people in the profession who genuinely could be trusted.

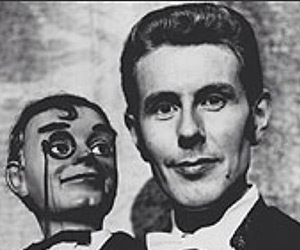

The recipient of his kindness, on this particular occasion, would be the comic and ventriloquist Ray Alan, who would later find fame in the Sixties with his distinctive dummy, the hoity-toity toff Lord Charles (a sort of linden wood-carved prototype of Jacob Rees-Mogg). Alan's potential as a performer was spotted by Bonn in 1952, when the then-little-known entertainer was standing in for another comedian on a variety show in Ramsgate, doing a 'bits and pieces' routine that involved mixing magic with impressions and ventriloquism (his dummy, in those days, was a much more modest sort of character called 'Steve'). Recruiting the young man for his own well-established touring company, Bonn became Alan's mentor, teaching him how best to develop his act, work on the quality of the script and make use of all the tricks of the trade.

Alan was on tour with him when he suddenly fell ill with bronchial pneumonia, collapsing in his dressing room after struggling through his spot on the show. A local doctor arranged for him to be rushed off to hospital in an ambulance, while all of his belongings were gathered together and placed in Bonn's car for safekeeping.

The tour went on while Alan remained in hospital, but Bonn made a point of calling Alan's mother every day to check on his progress and express his sympathy and support. When, after spending the best part of a month in bed, the young performer felt well enough to work again, he rejoined the tour in Manchester, on a Monday at the Ardwick Hippodrome, but it soon became obvious that, due in part to the powerful sulfa drugs he had been taking every two hours for the past three weeks, he was actually in a much worse state, mentally as well as physically, than he had previously thought.

It was at this point that Bonn really showed his kindness. At the end of that week, he gathered his company in the dressing room and, as usual, gave each of them their wage packets. Along with Alan's money, however, he also handed him a second envelope. 'Everything's in there,' he said, 'and you leave on Monday'.

Alan, now puzzled, asked him what he meant. 'You're going to Switzerland,' Bonn announced. 'But I can't go to Switzerland,' Alan protested. 'I can't afford it'. 'Yes, you can,' Bonn assured him.

It turned out that Bonn had contacted a manager at Thomas Cook's travel agency, explained the needs of his friend, and sorted out a package specially for him. Alan, urged on by his boss, then opened up the second envelope and found an airline ticket, a very generous hotel voucher and seventy-five pounds of traveller's cheques (worth about two thousand pounds by today's values) for him to spend during his stay there.

'But how can I possibly pay you back?' he asked, incredulously. 'Don't worry,' said Bonn. 'You'll pay me back five pounds for every week that you work'.

A very grateful Alan then flew off to Switzerland, recuperated properly in far more comfortable surroundings than he had ever experienced before, and eventually returned feeling thoroughly refreshed. 'Then after the first week back,' he would recall, 'he's paying me my money in the dressing room and I gave him five pounds. He said, "What's that for?" I said, "We had an agreement: I pay you a fiver every week that I work". He put his arm around my shoulder, smiled, and said, "It's all right, I've already deducted it - you've got a rise"'.

'What a wonderful man,' Alan would reflect many years later. 'And such a very, very, kind man'.

He not only continued touring with Bonn for the rest of the decade, benefitting immeasurably from the more experienced entertainer's advice, but also, when Bonn himself finally retired from performing in 1963, Alan asked him to become his manager and agent. Bonn agreed, and would continue in that role, supporting his friend, right up to his own death in 1977.

'I'll never forget him,' Alan would say by way of a tribute. 'He showed me so much faith, gave me so much encouragement, and he never expected anything back. If you ever need an example of how good people can be in this business, you can't go wrong with Issy Bonn'.

Roy Hudd would come to say much the same about Arthur Askey. The up-and-coming comedian (then in his early thirties) was struggling towards the end of what he would regard as his very own annus horribilis (or 'anus horribilis' as he preferred to call it), when the much older performer, completely unbidden, decided to intervene.

The year in question was 1969. It had actually seemed set, shortly before it had started, to become Hudd's annus mirabilis: 'I'd sat there with my wife on New Year's Eve and said, "This is going to be the best year I've ever had in the business!" Because I was going to be doing my first radio series, I was going to be doing my first television series, and I was going to be doing a play in the West End. It was going to be the year I became a star!'

The television series came first. Entitled The Roy Hudd Show, it was produced by John Duncan (who not only had worked with the star several times before, but had also, according to Hudd, overseen 'all the best things I have done on television'), it boasted scripts written by such leading figures as Keith Waterhouse, Willis Hall, Philip Purser, Pete Spence and David Nobbs, and it featured among its supporting cast the popular musical comedy star Joan Turner and the much-admired actor Freddie Jones. It all looked very promising.

It turned out to be a disaster.

Screened on ITV during February of 1969, it had been conceived as an innovative and somewhat 'edgy' late-night kind of comedy show (of a type and style that the BBC had been offering, to much critical acclaim, for much of the decade), with plenty of offbeat, surreal and satirical material (one sketch, for example, was called A Soft Landing on God, another episode offered several songs about death, while one of the regular sequences involved static cartoons with spoken captions). For some peculiar reason, however, the schedulers at ITV decided to give it an earlier slot, at 9.30pm, which was normally reserved for far more conventional mainstream programmes.

The result was that many viewers and critics alike were simply not prepared for the jumbled and jerky nature of the show. Not everyone hated it, but enough of them did to make the weekly round of reviews increasingly painful reading for Hudd and his team.

One critic declared that the show deserved the title of 'Rubbish of the night - if not of the week' for turning out 'so much downright unfunny "comedy"'. Another observer offered mock praise for the 'brilliant' decision to include a sketch about undertakers, sneering that 'it just about summed up the whole show - a dead loss'. Other reviewers dismissed the series as 'too much of a private joke'; 'juvenile'; 'plumbing the depths of inanity'; 'a waste of talent'; 'a load of bilge'; and 'exceedingly boring'.

That, for Roy Hudd, was strike one.

His new radio show, which was also called The Roy Hudd Show, came next. Produced by the very experienced Edward Taylor, it drew on material scripted by the likes of David Nobbs and Simon Brett, featured a big band and had Sheila Bernette as Hudd's comedy sidekick. It was, promised the team behind it, going to be a series that everyone could come to love and enjoy.

It turned out to be another disaster.

Broadcast on BBC Radio 2 during March, it seemed to those who already hated his TV show as little more than another unwelcome test of their tolerance, to which they responded by reprising their previous complaints. 'Roy Hudd's first radio comedy series has made a discouraging start,' wrote one unimpressed reviewer. 'Comedians depend on their scriptwriters, and, although six of them laboured at the first broadcast, the material they provided was feeble, impoverished stuff'.

That was strike two.

Next up, in April, was the West End play, which was called The Giveaway. This, Hudd had anticipated back on that heady New Year's Eve night, was destined to be the pinnacle of his glorious ascent to stardom.

Staged at the Garrick Theatre, it was a topical satire (about a suburban woman who wins a competition on the back of a cornflakes packet) written by Ann Jellicoe (whose earlier work The Knack had been a big hit first as a play and later as a movie). It was being directed by Richard Eyre (already a much-praised figure and a future artistic director of the National Theatre), it starred Rita Tushingham (one of the most fashionable young British movie stars of the time) and Dandy Nichols (who was currently in one of the most popular sitcoms of the time, Till Death Us Do Part) and Hudd himself.

It turned out to be the biggest disaster of them all.

Opening on Tuesday 8th April, it played to an audience that actually got smaller and smaller as the first night went on. At the curtain call, Rita Tushingham was loudly booed, a horrified Hudd stepped forward and told those who were booing her to 'fuck off,' several other members of the cast burst out in tears, and the production was deemed an immediate flop. 'Plodding, unoriginal and unfunny,' wrote one critic. 'Simply awful,' declared a second. 'The only unforced laugh it received,' wrote another critic, 'came when Hudd accidentally broke the flex on a telephone and had to improvise for a few seconds'.

It limped on for just three more days. The doors were shut on 12th April.

That was strike three. Hudd was out.

He would not work again for most of the rest of what was now an extraordinarily miserable year. His agent would spend the brief meetings they would occasionally have simply shaking his head and sighing. 'They don't want to know you, lad,' he would say, struggling even to look at his crestfallen client. 'I can't get you anything. They're saying you're box-office poison!'

Hudd didn't resent his agent for telling him all of this. He had already heard much the same sort of depressing things from plenty of other sources: 'They'd said I'd practically closed down ITV, ruined BBC radio, and turned off the lights in the West End!'

He was shattered. 'I really didn't know what to do,' he would recall. 'It was supposed to have been the year when everything really clicked, when everything went right, and everything had actually gone wrong. I honestly had no idea whether I was going to be able to stay in the business after all of these setbacks'.

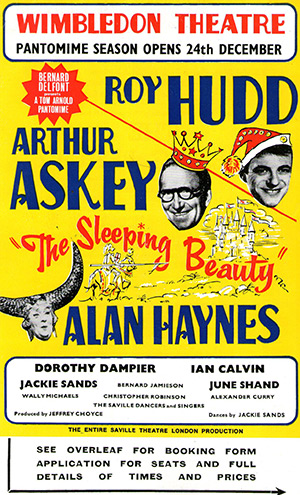

It was at this dark moment that a chink of light suddenly crept in. 'I got a phone call,' he later recalled, 'asking me if I'd be interested in going and doing a pantomime - Sleeping Beauty - that Christmas in Wimbledon. I thought, "Would I be interested???" I'd have done anything at that point, and, as I was living nearby in Streatham, I could walk there - which was just as well, because it was about the only way I could afford to get anywhere at that point!'

The star of the pantomime was going to be the veteran comedian Arthur Askey, and it was Askey who, in a very discreet way, was now trying to save Roy Hudd's year - and perhaps even his whole career. 'I only found out later,' Hudd would recall, 'but Arthur had said to the people, "Yes, I'd be interested in doing Wimbledon, but I must have Roy Hudd with me because we work marvellously together in pantomime - so if you get him, I'll do it"'.

It was an act of compassion that seemed to come out of nowhere. 'The truth was that I'd never even met Arthur in all my life,' Hudd would tell me. 'I'd always admired him, of course, but I'd never, ever, actually met him. But, it turned out, he knew that I was having such a terrible time, and he just wanted to help me out'.

The kindness counted. Hudd joined him in the pantomime, and Askey didn't mention anything to do with how or why he had been hired. He simply made Hudd feel welcome, valued and admired - and, in the weeks that followed, the pair of them were indeed marvellous together in that pantomime.

The acclaimed female impersonator Danny La Rue was so taken by the talent of the young comedian that he visited backstage after one performance (having been invited to attend by Askey expressly in the hope that his co-star would impress) and asked Hudd to join a West End revue he was planning for the following year. Roy, struggling not to seem stunned, stuttered his acceptance and they shook hands there and then. 1970 was already more or less booked up.

Hudd's luck, quite suddenly, had changed. The next year really would be a good year, and it was all thanks, even though it would be a very long time before he knew it, to Arthur Askey.

'Isn't that one of the best stories ever?' Hudd later reflected. 'What a wonderfully kind man he was. They always talk about what a load of rotters and scoundrels are in show business, but whenever I hear any of that I just tell people that story - and that shuts them up!'

Hudd, in turn, would be responsible for another such story himself, when, in a similarly unbidden act of kindness many years later, he came to the aid of an ageing comedy performer. This intervention happened as a result of Hudd's famously unquenchable curiosity about show business history.

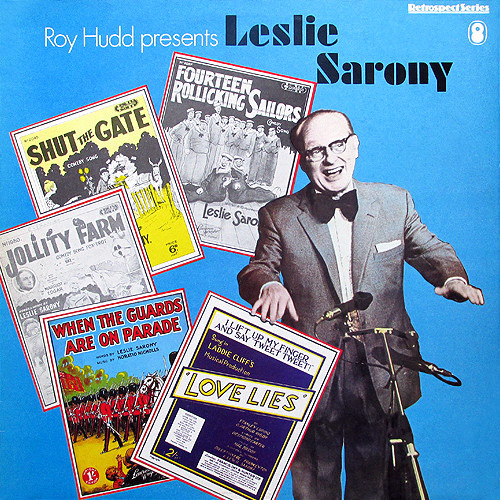

A great collector of music hall memorabilia, he was attempting, one day in the autumn of 1980, to complete an inventory of what was by now his huge archive of old comedy song sheet music. As he was noting down the details of each composition, one name in particular, through its sheer repetition, started to intrigue him. The name in question was that of Leslie Sarony.

Leslie Sarony had been an extraordinarily prolific, and very popular, writer of comic songs during the 1920s, 30s and 40s. First as a solo performer, and subsequently as one half of a double act, alongside Leslie Holmes, called The Two Leslies, he had been responsible for some of the most infectiously hummable and quotable comedy compositions of the era.

Silly, sometimes saucy, always playful little ditties such as I Lift Up My Finger and I Say Tweet Tweet, Umpa, Umpa (Stick It Up Your Jumper), Don't Do That to the Poor Puss Cat and I Like Riding On A Choo-Choo-Choo were some of the Great British public's earworms for many years, harmlessly addictive two-minute cheerer-uppers for a nation doing its best to battle through an economic depression. He came up with still more songs to lift the spirits during wartime, with recordings such as his version of (We're Gonna Hang Out) The Washing On The Siegfried Line quickly becoming classics of their kind.

By the Fifties, however, The Two Leslies had broken up, Sarony was back working on his own, and musical, and comedy, fashions had changed, moving rapidly away from middle-aged crooners in evening dress towards younger singers and satirists in sweaters or coloured suits. He never stopped writing, but most of his new songs were never heard, let alone recorded, and he spent most of the next three decades concentrating on acting rather than singing.

He proved himself, eventually, to be a versatile and interesting actor, working in sitcoms (such as I Didn't Know You Cared, playing Uncle Stavely), one-off episodes of such series as Z-Cars, The Sweeney and Minder, and the odd movie (including a minor role in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang), as well as appearing on stage in productions of Beckett, Chekov and Shakespeare. The neglect of his old songs, however, as well as his new ones, continued to niggle.

About four hundred of them had been published, but the royalties, by this time, were negligible, which only added to his sense of resentment, because, thanks to many poor business decisions, this once-wealthy man was now obliged to live alone (having long since been divorced) in much more modest circumstances, and reflect on the fame that had faded. When, on the odd quiet evening, he played one or two of his old shellac copies of his songs, every intrusive crackle reminded him of how ancient and fragile they - and he - now seemed.

He still performed some of them when he toured on the newly-formed veteran variety circuit, accepting the applause of a small and elderly audience, but what he longed to do was re-record them with more up-to-date arrangements that might make them sound more appealing to a whole new generation of listeners. The problem was that, in spite of his ongoing efforts, no record label seemed interested in such a project, and the sense of rejection had made Sarony quite a sad and, by this stage, rather bitter old man.

This is where Roy Hudd came in. Struck by how many comic songs in his archive Leslie Sarony had written, and how so many of them were considered classics of their genre, Hudd embarked on a mission to get them back into circulation. He had never met or had any other kind of contact with the man himself, and, beyond the songs themselves, knew little about him, but a producer friend was able to pass on his contact details, and he was determined to get in touch.

Sarony was thus greatly surprised when Hudd tracked him down at his humble little home in Streatham Hill and told him about his plan, but he was delighted that, at long last, and after he had more or less given up all hope, someone actually wanted to help him realise his dream of re-recording some of his best compositions. He did confess to a fear that his voice might not now be strong enough to stand up to a long recording session - he was, after all, eighty-three by this time and long out of practice - but there was no doubt as to how keen he was to attempt it.

Hudd thus proceeded to arrange for studio time, paying for it out of his own pocket, and contacted Sarony to confirm the details. The elderly singer and songwriter, upon receiving the news, said that he would be counting the days until he could once again step in front of the microphone.

'At ten-thirty in the morning,' Hudd would recall in the sleeve notes for the record, 'Leslie arrived at Anvil Studios and started to sing while I sat in the control box with our recording engineer, Eric Tomlinson. Eight bars in we looked at each other and Eric said, "He sounds exactly like he did in the thirties!" It was all still there, the immaculate diction, the timing and the just suppressed chuckle. A greatly over-used word but the session was magic!'

Sarony, determined not to waste this special opportunity, breezed through all fourteen of his songs, needing only a single take for each of them. There, freshly back on tape, were some of the precious comedy numbers - cheerful reflections on everything from the reassuring Britishness of Teas, Light Refreshments and Minerals to the exotic wonders of Gorgonzola cheese - which their creator had feared would remain trapped in the bygone age of music halls, gramophones and scratchy 78s. The act of bringing them back to life seemed to be bringing him back to life, as the adrenaline rush saw him dancing around the studio much like he had done back in his heyday.

Once the session was over, Hudd, thrilled with the results, congratulated his singer warmly and remarked that there must be enough other songs to fill a second album. 'Shall we do them next week?' said an ecstatic Sarony, and he really seemed to mean it.

Hudd's next challenge was to see what interest he could arouse among the record labels. It did not take him anywhere near as long as he had expected.

One of EMI's subsidiary labels, World Records, was happy to distribute the album. Being a home to many diverse types of music and spoken word recordings, with a special emphasis on the 'vintage' music of the dance band era, it had a strong mail order division, and knew how to market such a product.

The resulting album was called Roy Hudd Presents Leslie Sarony. It would reach the shops just in time for Christmas.

It was a deeply emotional moment for the eighty-three-year-old Leslie Sarony. 'Umpa Umpa' he could hear people out and about on the streets singing all over again, 'stick it up your jumper!' His treasured songs had, at long last, come back to life.

Suddenly more offers came in for him to perform again as a singer and musician. The BBC filmed him reviving his old act. The Songwriters Guild of Great Britain gave him a special award for his lifetime's achievement as a composer. He even received an invitation to take part in his second Royal Variety Performance - a full forty-five years after the last one.

He was as grateful to Roy Hudd, for that gesture, as Hudd had been to Arthur Askey. Through the kindness of another stranger, one more comic had made a comeback.

So although, as Woody Allen once sagely observed, show business can often seem to be 'worse than dog eat dog. It's dog doesn't return dog's phone calls,' there really can still be times when the hardness gives way to something quite heartwarming. It thus feels, especially at this festive time of year, worth raising a glass to such days of decency, and wishing for more in the future of the same.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more