Pete and Club: Peter Cook's Establishment

The most genuine satirists are their own best and most relentless hecklers. When Peter Cook announced at the start of the Sixties that he was opening a club in Soho, he added that it would attempt to emulate all of those political cabarets of Berlin in the Thirties 'which did so much to prevent the rise of Adolf Hitler'.

It was the perfect promotional put-down, because satirists need to be realists, not idealists, and never be inclined to romanticise the nature of their game. Satire should pursue its ends, not preen about its means, and Cook knew that, ever since classical times, when Cicero's mockery of the hierarchy saw him meet the most grisly of symbolic fates (with his writer's hands chopped off and his orator's tongue stabbed repeatedly), those in power have many ways of thwarting one's charge for change.

Cook still wanted to go ahead, but he wanted others to do so, too. A centre of irreverence was thus required, a place where the wits could win.

The idea for a satirical club had first come to him in the spring of 1957 during the year he spent abroad, in between leaving Radley College and starting at the University of Cambridge. Aged nineteen, he was preparing for a degree course in Modern and Medieval Languages by soaking up some culture in the fleshpots of France and Germany.

It was while he was in Berlin that he took the opportunity to visit the city's most notable political cabaret club of the time, The Porcupine. It proved to be something of a disappointment, with the young but precociously sharp-witted tourist finding the local humour 'very juvenile', but, as he took in the lively atmosphere, he couldn't help but wonder how a similar sort of venue, sporting a superior set of acts, might fare if based in London.

The appeal of such a club was the freedom it afforded controversial comedians. Back in those days in Britain, censorship was still prevalent in the theatre, with the Lord Chamberlain possessing the power (first granted in 1737) to prohibit public performances, or cut any line or scene, when he felt 'it is fitting for the preservation of good manners, decorum or of the public peace so to do'. The club format, however, was outside his formal authority, and Cook dreamed of using such a place to safely satirise the status quo.

When he returned to England, and settled into Cambridge, he kept that particular thought largely to himself in the hope that no one else would come up with a similar idea before he had the chance to turn his own into a reality. Upon graduating three years later, having already proven himself (by dominating the Footlights Society, writing material for a West End revue and launching a new age of satire as a member of the Beyond The Fringe quartet) to be by far the most gifted comic spirit of the up-and-coming generation, he moved to London still determined to act on his earlier ambition.

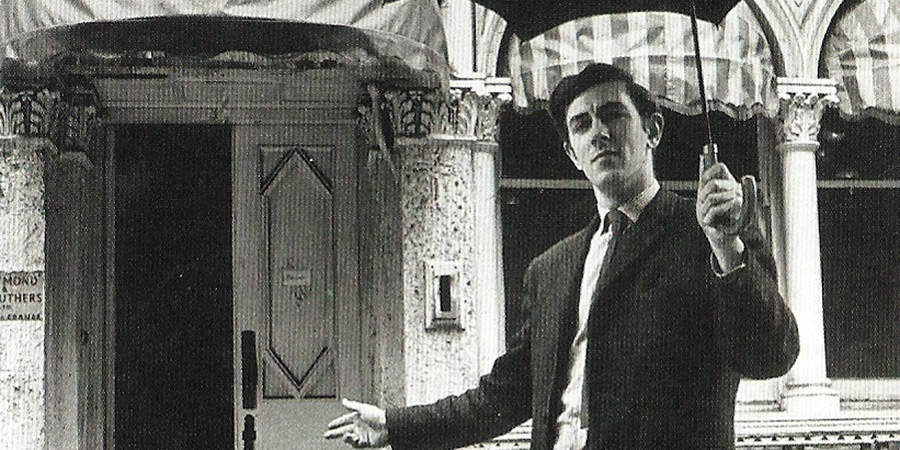

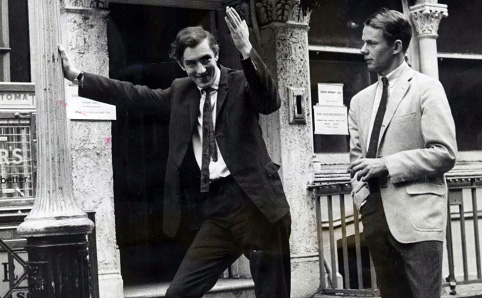

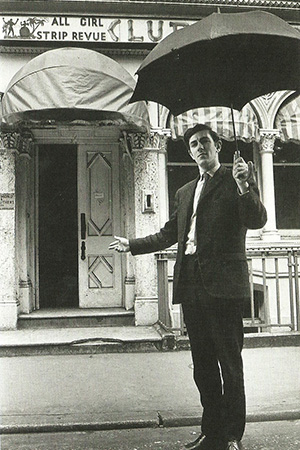

His first step in this direction was to find some appropriate premises. After sounding-out various theatrical associates and wandering around certain selected areas, he fastened upon a seedy-looking old building at 18 Greek Street deep in the heart of Soho.

It was now in a discouragingly decrepit state, with peeling paint, smashed windows, cracks running along the grubby walls and holes scattered across the floors. Behind the darkness and beneath the dust, however, it actually boasted quite a rich and colourful history.

It had spent most of the nineteenth-century, and the early part of the twentieth, as the primary warehouse of Berry & Lloyd, a rather grand wholesale 'soap and general perfumery' business. Boasting of its many envious imitators, it frequently placed announcements in the newspapers, warning prospective purchasers that only packaging bearing the address '18 Greek Street' contained the genuine and much-sought-after flesh-freshening products (such as their 'highly scented Brown Windsor Soap').

The property also had a number of notable politically subversive connections. Its upstairs rooms had been loaned, for a very brief but eventful period in the mid-nineteenth century, to a group of radical political reformers called the Universal League for the Material Elevation of the Industrious Classes (some of whose supporters would eventually prove pivotal in winning male workers the vote). A little later on in that century, the building became one of the temporary headquarters of the ever-evolving method of historical materialism, when Karl Marx, along with various visiting representatives of the International Working-Men's Association, used its rooms for fierce and forceful debates concerning the nature of dialectics, determinism and the best possible strategies for the revolutionary movements in France, Germany and Russia. It also served for a while after the Second World War as the head office of Plato Films, which had links to the Soviet Union and specialised in distributing Russian-themed movies.

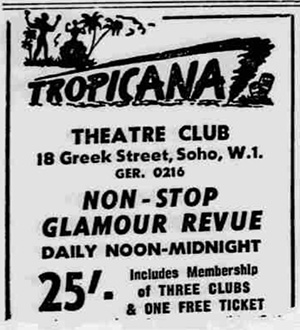

By the late 1950s, however, after a succession of short-lived residencies of an increasingly dubious nature, it had become a strip joint called the Tropicana Theatre Club. Serving up a 'non-stop glamour revue' every day from noon until midnight, it catered to Soho's raincoat brigade until most of them were lured away to the newer, smarter, slyer set of sex clubs that were sprouting up by the dawning of the next decade.

Forced into receivership at the end of 1960 following a police raid, the building had been boarded up and abandoned for several months - with plastic chandeliers hanging precariously from the ceiling, countless discarded G-strings and used condoms left scattered all over the sticky beer-sodden floors - until Cook came across it and, loving its location, leased it from the liquidators on the cheap. Now aged twenty-three, he did not yet own a home of his own but he did now have a dilapidated place of public entertainment.

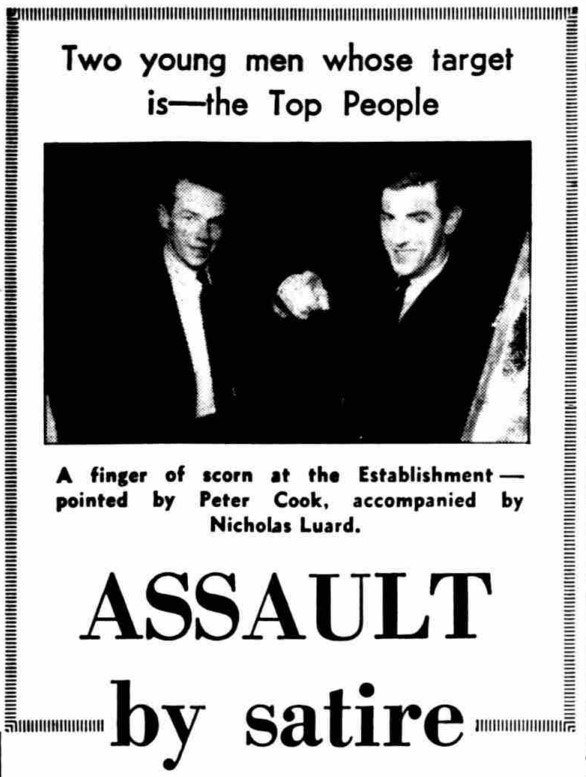

His second step was to find someone who could provide him with the financial expertise to turn this insalubrious-looking dump into a viable working venue. The person he picked for this was a contemporary from Cambridge called Nicholas Luard.

A former treasurer of the University's Footlights Society, and one of the few people with whom Cook had shared his vision of bringing Berlin-style cabaret to London, he was currently working in America on a graduate fellowship when the telegram arrived from his old friend: 'Have premises. Come home'.

Luard duly came home, listened excitedly to Cook's plans ('Fires and firecrackers need ignition,' he would say. 'Peter's pockets were always full of matches'), and promptly agreed to form a partnership with him to push on with the project. Pooling their resources to provide £25,000 of investment, they thus set up a company called Cook & Luard Productions in a tiny office at 5-6 Coventry Street and started getting things done.

They called in a mutual friend, the much-admired Irish architect and interior designer Sean Kenny, to oversee the gutting of the building and its subsequent transformation into a spare but stylish new arena for sophisticated satire, using pine, hessian, steel and glass to make it seem suitably sparse and smart, with black paint for the interiors and pink for the exterior, and fashionable sisal bouclé carpets covering the floor. He achieved all of this at such an extraordinary pace that, within just a few months, it was almost ready to open for business.

A bar and restaurant were installed on the ground floor, with a chef being poached from the Mermaid Theatre, and Bruce Copp, the former general manager of the same venue, was hired to run that side of the enterprise. Beyond this, at the far end of the narrow but deep premises, was the main auditorium, which was able to seat about ninety people.

The basement was also cleaned up and re-furnished, with a tiny kitchen tucked away in a corner, and a serving hatch and pulley system to transport the dishes up to the waiting staff. A postage stamp-sized stage and dance floor was added to the area so that Cook's Beyond The Fringe colleague Dudley Moore could have a residency there playing jazz piano with a couple of other musicians.

The young artist Roger Law (who, as one half of Fluck and Law, would later be responsible for the ITV satire puppet show Spitting Image) was also reserved a generous space near the entrance - a 14ft wall opposite the main bar - to sketch a topical cartoon every night, helping to make the building look as timely and engaged each day as a national evening newspaper. It was also arranged to decorate some of the other walls with unflattering caricatures of the so-called great and good, which would be swiftly and gleefully replaced whenever any of them faced their inevitable fall from power.

A place was also found, upstairs, for a small studio for the photographer Lewis Morley (soon to produce the iconic portrait of a nude Christine Keeler sitting the wrong way round on a Habitat chair). The arrangement was that, in return for free access to the entertainments below, he would roam the rooms chronicling many of the club's key moments just as they happened.

One thing that still required a solution, however, was the question of a name for the new place. Cook knew that he wanted to take on the Establishment - the term popularised in the Fifties by the political journalist Henry Fairlie to describe 'the whole matrix of official and social relations within which power is exercised' - and so he decided that it would be a suitably ironic gesture for his club to adopt it as its own name. Those who were anti-Establishment would thus now be members of The Establishment. 'It was the only good title,' Cook would say, 'that I ever thought of.'

There were plenty who did want to be members. Once invitations were issued over the summer - a year's subscription was to cost three guineas, with a founding life subscription to cost twenty guineas - no fewer than seven thousand people rushed to sign up (even though the place could only hold, at a squeeze, about five hundred people at any one time). The initial list included such eminent names as Graham Greene, Isaiah Berlin, J.B. Priestley, Yehudi Menuhin and Somerset Maugham, as well as numerous other writers, poets, actors, artists, academics, politicians, musicians and, of course, comedians. Cook also dispatched a couple of assistants to the Blue Boar Hotel in Cambridge to ensure that plenty of his old Footlights friends would be added (at slightly reduced rates) to the members' register.

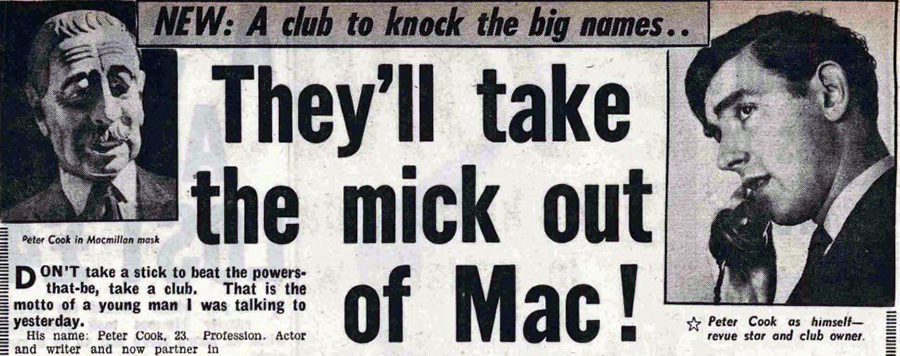

The press coverage that preceded the grand opening was certainly designed to whet their appetites. 'He will be deflating anybody who thinks he is a Somebody,' promised one report of Peter Cook's plans. The ambition for the club, predicted another excitedly, was 'to take satire to the brink of the libel precipices'. The attacks on authority, added another, would aim 'to draw blood'.

'What we really want to do,' Cook himself put it more succinctly, 'is to get back to the old art of abuse. We will be after the pompous, the vain, the arrogant and the silly. There's no shortage of targets.'

There would be a few more hiccups before it all actually started. The opening night had originally been announced as due on the 28th of September, but, as so often happens with such keenly-anticipated events, various complications forced the big day back by a week. In the meantime, teams of electricians and carpenters moved about the place as they hurried to get every outstanding task completed, while more wooden tables and chairs arrived, crates of drink were delivered, and Sean Kenny fussed over the finishing touches to the furnishings and set designs.

The Establishment finally opened its doors on the evening of Thursday 5th October 1961. It was, quite predictably, a glamorously chaotic affair, as the surrounding streets clogged up with cars and crowds, cameras flashed and countless public figures were encircled by reporters outside the front door.

Swarms of people swept into the building - Cook had made it clear that the seats would be made available strictly on a first come, first served, basis - and soon filled up all of the available space. According to one frustrated eye-witness, 'the hordes of invited and uninvited guests made it impossible for more than one-in-five to get anything like a good view of the opening show,' and many had to make do with listening to the proceedings from back at the bar. The same observer noted that the second show of the night featured Cook and his fellow members of the Beyond The Fringe quartet, 'but by that time I had retired exhausted, leaving a few inches of space for one of the club members waiting outside in the street in a slightly exasperated queue'.

The daily schedule during those first few months would take the following form: old comedy movies - many of them featuring The Marx Brothers - were shown during the early afternoon while only the bar was open for business; the first tables in the restaurant became available for 7:30pm, and then, after all the plates were hurriedly cleared away ('If they've come here just for the food,' Bruce Copp would say, 'they must be mad'), the opening show of the evening followed at 8:15pm (lasting about ninety minutes), followed by another sitting of the restaurant, and then the late show arrived at 10:45pm.

Drinks were available from the bar until 3am, but, because the licensing laws of the time prohibited the selling of alcohol after midnight without the accompaniment of food, an unappetising pile of thin and curling sandwiches was thrust on to thirsty customers during the early hours of the morning. Some worse-for-wear members merely tucked them into the chest pocket of their jacket, like breaded handkerchief squares, and carried on drinking.

What was most striking during those days was just how packed-out and lively the venue always was. Right from the start it acted as a magnet for all of those who would soon be associated with the London of the 'Swinging Sixties'. Every night it was common to catch a sight of such celebrities as the designers Mary Quant and Ossie Clark; models Jean Shrimpton and April Ashley; critics Kenneth Tynan and George Melly; directors Joan Littlewood and Peter Hall; actors Michael Caine and Terence Stamp; and, a little later on, the musicians John Lennon and Paul McCartney; along with visiting Hollywood stars such as Jack Lemmon, Cary Grant, Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum and Eartha Kitt (the latter of whom was 'so enamoured of Peter Cook,' according to Bruce Copp, that she ended up having 'to be restrained from coming in').

John Le Mesurier was usually to be seen in the basement, crumpled contentedly in a chair, blowing smoke rings and drinking dreamily while listening to mellow jazz. Another regular was the infamously tired and emotional journalist Jeffrey Bernard, who seldom ventured far from the bar. The novelist E. M. Forster was often to be found enjoying long and leisurely meals in the restaurant, mumbling ancient gossip about members of the Bloomsbury Group. Then there was the notoriously louche Labour MP Tom Driberg, 'who used to come to the club,' Copp recalled, 'and grab waiters by the balls'.

The vast majority of the clientele, of course, were there for the cutting-edge comedy, which was so addictive that many tried to slip in every evening. Jean Hart, who worked and sometimes performed there, would sum up its seductive appeal as being like 'a great dinner party with the best minds and the funniest people'.

The evening's early show usually featured the club's resident company, which included (when not otherwise engaged) John Fortune, John Bird, Eleanor Bron, David Walsh, Hazel Woodvine, John Wells and Jeremy Geidt. The late show was mainly reserved for whatever acts Cook and Luard could find, and afford, to showcase as the major stars of that night.

Peter Cook himself was appearing at the time in Beyond The Fringe at the Fortune Theatre in Russell Street, but, during those early days of The Establishment, he would drive back over to Greek Street as soon as he completed his curtain calls, park illegally outside the club (considering the £6 fines each week to be something of a bargain, he never minded when the vehicle was towed off to a pound in Waterloo), bound into the building, grab a drink and a cigarette and then go straight up on stage to open the late show with ten minutes or so of brilliantly improvised observations about politics, society, boring individuals and busty substances. He would sometimes be joined a little later by his Fringe co-stars Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and/or Jonathan Miller, along with one or two of his other comedy colleagues (including Spike Milligan, Anthony Newley and the musical troupe The Alberts), and many of these performances, according to some of those who witnessed them, were of an exceptional quality.

The club's all-purpose reserve performer, whenever anyone was forced to drop out at the last minute, was David Frost. An obsessive imitator of Peter Cook since his Cambridge days, thus earning from his idol the sobriquet 'The Bubonic Plagiarist,' Frost would race over to the building whenever the call came in, pocket his usual pay of a crumpled five-pound note from the till at the bar, and then leap up on stage and launch into his ersatz E. L. Wisty routines. 'None of [the regulars] liked Frost,' Bruce Copp would recall in his memoir, Out Of The Firing Line ... Into The Foyer, 'but he was able to go up on stage and stand in as a sort of understudy.'

He only got into trouble when, one afternoon, he was discovered lurking in Cook's office, having picked the lock of his filing cabinet, reading through all of the comedy scripts that Peter had received and dumped straight into the drawers. Cook continued to tolerate him, being more amused than angered by his naked ambition, although he would later confess that his one great regret in life was having once saved Frost from drowning.

It was not long before The Establishment, thanks to all the money that was now pouring in, was able to host some of the most significant topical comedians of the day, not only in Britain but also internationally. America's latest enfant terrible Lenny Bruce, for example, was flown over in April 1962 for a month at the club.

His residency would prove to be just as dramatic and eventful as it had been hoped ('Who's masturbated yet today?' was one of his opening questions to the audience). His humour, with its unprecedentedly direct engagement with themes relating to sex, politics, religion and death, provoked page after page of outrage in the papers (The People headline shrieked, 'He makes us sick,' while the Daily Sketch snarled, 'It stinks!'), and inspired countless other young comedians (who saw him as a sort of 'degenerate matinée idol') while angering innumerable conservative figures (some of whom kept calling for him to be banned and deported).

The one drawback during his stay was the fact that he was not always well enough (nor coherent enough) to step on to the stage. He missed several nights after being struck down with septicaemia, missed another after raiding Peter Cook's bathroom cabinet and mistakenly swallowing some laxatives, and was absent once again after doping himself up into a motionless daze. His stoner's hunger also got him into trouble, such as when, for want of any alternatives, he swallowed greedily someone's home-made rabbit pie, hastily embellished by a large chunk of marzipan, a jar of marmalade and a quart of chocolate ice cream, and was then violently sick.

Bruce hired a glamorous-looking female doctor from Harley Street to administer a cocktail of illicit drugs to him every day of his stay, but his addiction was by this stage so advanced that he often felt the need to add to the intake himself. On several occasions, for example, he was spotted by staff removing his shoes and socks and injecting heroin into his ankles.

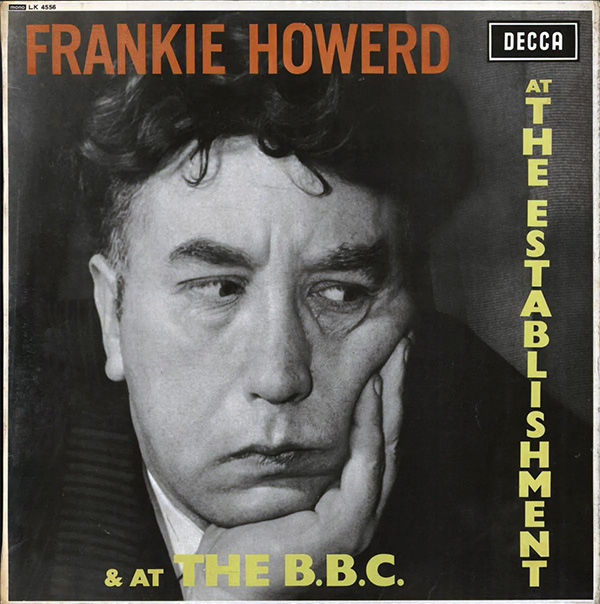

A more surprising, but no less successful, booking (just a few months later) was Frankie Howerd, whose career had been in the doldrums before Peter Cook persuaded him to re-package his act for a new generation. Gifted some fresh topical material by Johnny Speight, Galton & Simpson and Eric Sykes, Howerd was still so apprehensive about stepping foot into such a high-profile centre of contemporary satire that he was literally shaking with fear before going out on stage, with Bruce Copp assigned the task of holding his hand to calm him down, but his flabber had never been so gasted by the warmth of the welcome he received.

'I'm sorry,' came his mock-apology, 'I'm no Lenny Bruce. And if you've come here expecting a lot of crudeness, and a lot of vulgarity, I'm sorry, but you won't get it from me, so you might just as well piss off now!' Moving on - much to the watching Cook's delight - to bite the hand that was now feeding him, he punctured the pretentions of the more precious of the regular members by dismissing the venue as 'only a snob's Workers' Playtime, let's face it,' and then he launched into a way of taking on this subversive comical trend that would help nudge it towards more of a mainstream audience.

Talking political satire as though he was gossiping over the garden fence - '...No, liss-en, I was - no, honestly - I was out on a cycle rally - it can be fun, it can be fun - and we were passing by Chequers...' - he proved a revelation in such a fashionable context, such as when he cut down to size the Prime Minister of the time, Harold Macmillan, by treating him like a sitcom character: 'I said, "Harold, be careful, do! Don't rush, I beg of you. Don't rush!" But, you see, I don't think he got the message. No. I don't think he got the message. Of course, it's very difficult when you're shouting through a letterbox.'

Not all of the engagements were anywhere near so successful. While Cook and Luard tried hard to promote numerous new young talents, for each one whose progress was accelerated by the experience - such as Ivor Cutler, who was given a long run of cosy late-night slots to win over audiences with his distinctive brand of whimsy - there were several others whose prospects took a hefty dent.

The young Barry Humphries, for example, having been recommended to Cook by the poet John Betjeman, tried out his then-relatively new creation of Edna Everage at the club and was met with a mixture of bewilderment and indifference. 'There just happens to be a curious quality about this long-haired Australian gent' was about as good as it got for him, in terms of critiques, during his very brief stint at the club.

The stage was not the only place where people could take a hit. There were quite a few nights, when the comedy cut close to the bone, that ended up with flying fists and angry shouts amongst the audience. On one famous occasion, for example, the Galway-born actor Siobhán McKenna, who was very drunk at the time, rose to leave midway through Lenny Bruce's act in protest at his repeated attacks on the Roman Catholic Church. On her way out, Peter Cook tried to remonstrate with her, whereupon she grabbed and held on to his tie while one of her escorts punched him squarely on the nose. 'These are Irish hands,' shrieked McKenna melodramatically, 'and they're clean!' 'This is an English face,' replied Cook curtly, 'and it's bleeding'.

The Establishment club burnt so bright for a while, and then it burnt out. There were a number of reasons for its premature demise.

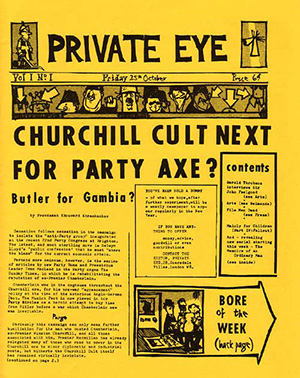

One involved the rise of Private Eye. Founded shortly after The Establishment towards the end of 1961, it was bought by Nick Luard in May 1962 for £1,500, then taken over by a somewhat reluctant Cook, and its office was moved inside the club premises. This union of the two satirical outlets made plenty of sense at the time, but it sowed some seeds of resentment internally, with stalwarts in both camps coming to suspect that the owners were now spreading themselves too thinly.

Another factor that followed soon after was the prolonged absence of Peter Cook, who, for much of the time from the autumn of 1962 until the summer of 1964, would be away in America, performing in Beyond The Fringe on Broadway. Nick Luard was left in charge, but, lacking Cook's languid charm, he started alienating some of the club's staff and supporters with what they regarded as his arrogant and abrupt manner, along with some eyebrow-archingly capricious and expensive decisions, and his clashes with Bruce Copp especially would do much to undermine the working atmosphere.

Another problem concerned the criminal class. Right from the start, The Establishment (like many other businesses in the area) had been a target for local gangsters, who often visited to issue threats in a bid to extract protection money. Peter Cook had proven remarkably calm when dealing with such figures, disarming them with his good manners and confusing them with his humour. One particularly aggressive bunch of thugs had fled in embarrassment after Cook loudly suggested that they continue their routine on the stage, while he stunned the Kray twins by politely declining their offers of 'help' and ushering them straight back out through the door.

Once Cook was on the other side of the Atlantic, however, the club started to crack under such nefarious pressure. The mobsters, having failed to gain control through their usual means of direct threats, started pursuing a more devious strategy by planting their own people among the staff with instructions to undermine the smooth-running of the operation.

Petty thefts became rife - several cine projectors were stolen, as were a number of microphones, stage lights, furniture, pictures and props - and there was clearly some blatant internal corruption. On one occasion, for example, fifty crates of wine were delivered to the club, only for forty-nine of them to be slipped straight back out of the cellar and on to the street and were never to be seen again.

In September 1963, with their finances drained by such lax management and internal sabotage, Cook and Luard's jointly-owned company went into voluntary liquidation with debts of nearly £65,000. The solicitor at the subsequent (very heated) bankruptcy hearings said angrily that Luard was a 'stupid and foolhardy' person who had 'no idea how to run a company'. Cook, still stranded in America, was left feeling hurt and betrayed.

Then came another, even more dangerous, set of gangsters, led by a large Lebanese character called Raymond Nash. A former partner of the recently-deceased slum housing landlord Peter Rachman (a ruthlessly exploitative operator whose name, wrote one newspaper, had 'added a new word for evil to the English language') and one of the most powerful figures in the area, it was rumoured that Nash dealt with those with whom he disagreed by nailing them to the floor through their knees. Having waited patiently as all of these weaknesses crept into the club, he now went in for the kill.

Later described by Cook as 'a crook, and a tough crook at that', Nash snapped up The Establishment at a bargain price and wasted no time in stamping his own crude signature on its image. 'It soon reverted to a sex cinema,' Cook observed acidly, 'dedicated to the overthrow of the government and all that it stands for.'

The Establishment club lasted for just three years, but they could hardly have been three more eventful and memorable ones. Like The Beatles' Apple (dis)organisation a few years later in the same decade, it was driven by what made the world good, and broken by what made it bad.

The only physical trace that exists to acknowledge its former existence is a plaque above the entrance, which is now the doorway to the distinctive delights of the 'funky cocktail bar and restaurant' Zebrano. Its spiritual legacy, however, continues to be discernible and available for those satirists who seek to please others rather than just themselves, rebel with style instead of smugness, and much prefer the odd noble failure to a stretch of shallow success.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more