Do I have to spell it out? Neil Innes own right

The current and forthcoming commemorative events (including a book and a tribute concert) relating to the life and career of Neil Innes could surely not be better deserved, because, aside from being an eminently talented, versatile and witty writer and performer, he was also a very nice man. There, I've said it: Neil Innes really was nice.

It feels almost obligatory, these days, to apologise for stating such a thing, because, in the peculiar popular culture of today, such an admission is likely to be deemed, by a depressingly large number of people, something of a deal breaker as far as open adulation is concerned. Arrogance, entitlement, irresponsibility, insensitivity, vindictiveness and even violence - they all seem to be excused, or even embraced, by those who are so scared of seeming bland and boring that, in the hope of appearing a bit more 'rock and roll', they bow down and worship any old kind of run-of-the-mill rebel.

Being nice just doesn't cut the mustard as far as most of the media are concerned. It's being nasty that gets you noticed.

This is all quite a shame, because, if most of us are to be honest about what we claim to most value, a great guy who is also a good guy ought to be our ideal. A nice hero, to paraphrase John Lennon, is something to be.

And that brings us back to Neil Innes, who portrayed John Lennon in The Rutles as, of course, Ron Nasty. Lennon, being no stranger to either the public impact of an image or the personal importance of self-critique, appreciated that joke immediately, as did Innes about the one, with greater subtlety, that he was making about himself.

The story of his life and career in music and comedy is full of such self-aware and self-deprecating grace and playfulness. It's what talented people, if they are also genuinely nice, do so well.

Neil Innes was born on 9th December 1944 in Danbury, Essex, but, due to his father being a warrant officer in the British Army, spent the first few years of his childhood in Germany (where Innes Senior was stationed by the Rhine) before returning to England to complete his formal education in Norfolk. Drawn to drawing, he went on to train at the Norwich School of Art before moving to London to begin a degree course in fine art at Goldsmiths College.

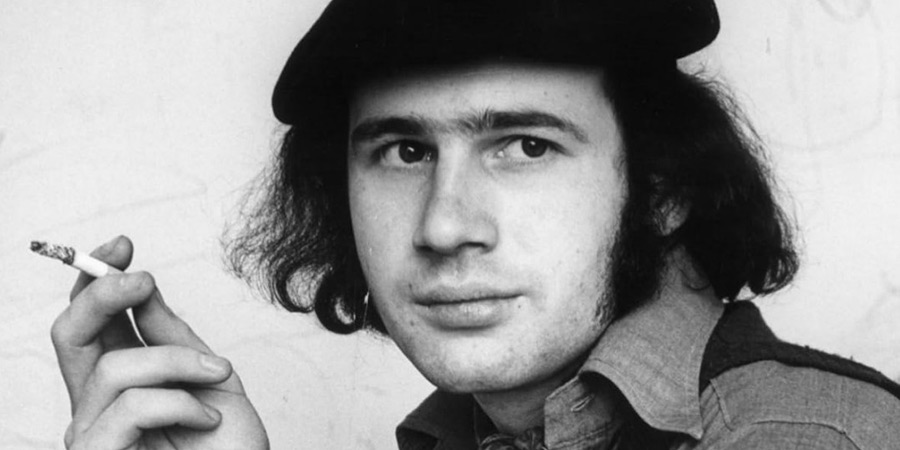

It was during his early days at Goldsmiths that, like so many young art school students of his generation (the very long list would include John Lennon, Pete Townshend, John Cale, Ray Davies, Ronnie Wood, Bryan Ferry, David Bowie, Syd Barrett and David Gilmour), he stretched over into music. He joined a semi-professional band called, initially, the Bonzo Dog Dada Band (until, after tiring of having to explain Dadaism to the uninitiated, they renamed themselves the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band).

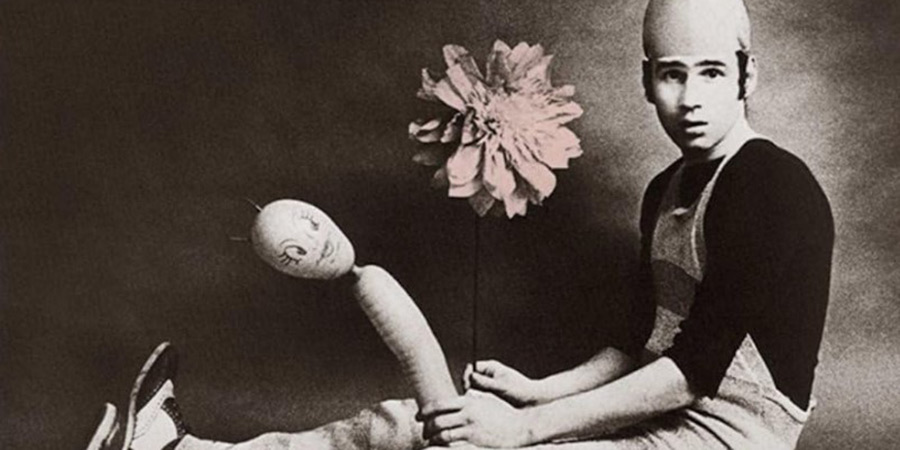

Also featuring Viv Stanshall (vocals and various wind instruments), Rodney Slater (saxophone/clarinet), Vernon Dudley Bowhay-Nowell (bass and banjo), Bob Kerr (trumpet), Martin 'Sam Spoons' Ash (percussion), 'Legs' Larry Smith (drums) and Roger Ruskin Spear (all sorts), Innes (belatedly putting to good use all of the music lessons he had endured as a child) was brought in as a pianist and guitarist as well as a budding songwriter. Part performance artists, part cultural curators, part musicians and part mischief-makers, what they had in common was a deep-rooted aversion to having anything in common with anyone else, with a drive to turn being, as much as doing, into an art form.

Instantly eye-catching for their quirky but peacock-proud anti-fashion sense (Stanshall, for example, would often wander about in a Victorian frock coat, checked trousers, pince-nez spectacles and a pair of large rubber false ears on his head whilst casually carrying an antique euphonium under his arm), they were bold and bright bricoleurs, gleefully picking and choosing from the past as well as the present to piece together something peculiar that pleased them. They particularly relished searching through the piles of old vintage shellac discs for sale at Deptford Market, seizing on such intriguingly odd-sounding titles as Hunting Tigers in India, I'm Gonna Bring a Watermelon to My Girl Tonight and The Stork Has Brought a Son and Daughter to Mr and Mrs Mickey Mouse, and then re-working them into new arrangements with accompanying routines that would feature all kinds of strange sound effects, props and costumes.

Neil, while enjoying the evening sessions with his new bandmates, had by no means yet given up his ostensible day job as an art student. He was actually showing plenty of wit, imagination, industry and invention in these activities: one of his creations involved a rolled-up piece of painted canvas whose contents were revealed by 'playing' it on a Dansette record player, while another was a Heath Robinson-style interactive contraption within a picture frame that featured a metal ball that rolled from one side to the other under various bits of balsa wood and ended by ringing a little bell. The problem was that, as far as his tutors were concerned, he did not seem to have quite the right kind of pliable disposition to produce what was then desired and required for a National Diploma in Design. The result was that, as time went by, he invested more and more of his energies into the Bonzos instead.

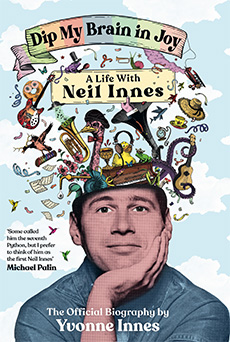

He had, by this time, met Yvonne - the kind and clever woman who would become his soul mate. A fellow student at Goldsmiths, her first impression of Neil, as she now recalls in her essential just-published memoir about him entitled Dip My Brain in Joy, was that he was 'funny, mischievous and' - of course - 'just so nice'.

'I think you should know', he told her solemnly during their first date, 'I'm losing my hair'. Still looking quite hirsute at that time, his furrow-browed honesty made her laugh, as did most other things he said and did, and they soon found themselves falling in love.

The couple were married on 5th March 1966 at Greenwich Register Office, surrounded by family, friends and Bonzos. There was only time afterwards for a brief celebration in a nearby pub before everyone moved on to Ilford for yet another low-key, low-paid, gig.

The Bonzos were not touring, in those early days, on the voguish pop and rock circuit of the era. They mostly played the old run-down variety theatres, along with an eclectic network of small and insalubrious London pubs and the smoke-smogged and ale-stenched northern working men's clubs, rubbing shoulders and other things with a motley collection of ageing jugglers, cackhanded magicians, wonky-wigged crooners, eccentric dancers and a man who kept whirling his wife around in a circle just above the floor as if she was an industrial vacuum cleaner. These were the kind of quaint and curious 'turns' that served as further inspiration for the whimsical style that the Bonzos were developing in their own increasingly distinctive act.

By the mid-Sixties, as more conventional figures and forces began to catch up with their own eclecticism in popular culture, the Bonzos suddenly found themselves being featured more prominently in the whole satiric, psychedelic, past-gazing, future-glimpsing, boozy, woozy, hazy, Granny Takes a Trippiness and Sgt Pepperishness of it all, and they were suddenly mixing socially with, and receiving compliments from, the great and the good and the gear of the era.

The Beatles added the Bonzos to the cast of their Magical Mystery Tour TV movie. The Who and The Kinks took them as their support act on tour. Neil even had occasion to stand next to Jimi Hendrix in the men's room of a Los Angeles club ('You know,' said Hendrix warmly as he looked sideways, 'we're doing the same thing'. 'What - peeing?' asked Neil. 'No,' replied Jimi, 'I mean onstage'). They were brought in by the up-and-coming Oxbridge comic writers and performers Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Eric Idle to be the house band on their new TV series Do Not Adjust Your Set. The outliers were playing at being the insiders and, in the process, they were having the time of their lives.

Neil's own increasingly prominent role in the group as a songwriter would itself be underlined when, in 1968, they recorded one of his catchiest compositions, I'm the Urban Spaceman. Produced by Paul McCartney under the pseudonym of Apollo C. Vermouth, it was a big hit, reaching number five in the UK charts and bringing the band unprecedented exposure.

They went on adding to their already hugely admirable and endlessly entertaining album output (which thus far consisted of 1967's Gorilla and 1968's The Doughnut in Granny's Greenhouse) with the further inspired instalments Tadpoles and Keynsham (both 1969), made an appearance at the high-profile Isle of Wight Festival, and also had a go, in their own inimitably chaotic way, at exporting their art to America. Eventually, however, by the time the Seventies had arrived, the band, exhausted from battling with managements and labels and various other big beasts of the industry to protect and preserve their free and irreverent spirit, finally fell apart.

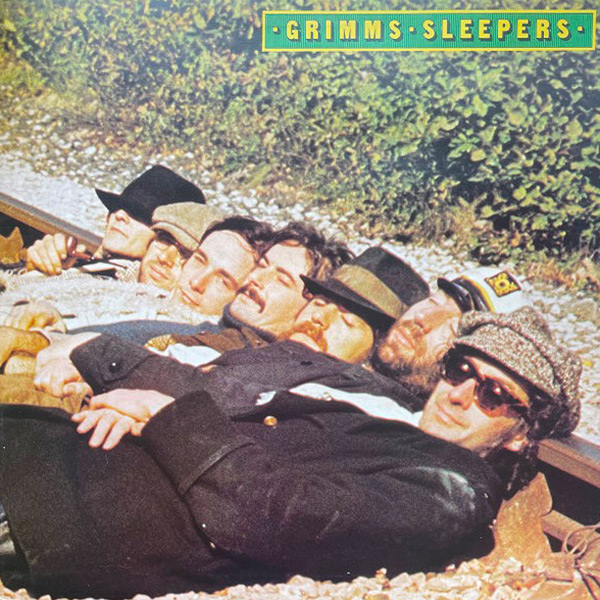

Neil's next big adventure would be a kind of counter-cultural super group by the name of GRIMMS. An acronym of the founding members - the ex-Scaffold Scouse comic and singer John Gorman, the Harrow-born singer-songwriter Andy Roberts, Neil himself, two more Liverpudlians Mike McGear and Roger McGough (both also resting-Scaffolders) and Viv Stanshall - GRIMMS mixed up and messed about with music, poetry and comedy with a gleeful sense of abandon that positively relished the sheer hit-and-missness of each idiosyncratic adventure.

They toured, they made records and they made the odd appearance on TV and radio. Neil sometimes took to the stage on stilts, often wore a plastic duck (the 'Quaksie' as he called it) on top of his thinning-haired head, and performed such compositions as the instrumental tribute to his own lavatory, Twyford's Vitromant (the topic of toilets, and the need to 'get up and go' to visit them, would become something of an Innes staple, without ever seeming, for want of a better word, strained), while various colleagues wrestled while reciting poetry, sang songs via a ventriloquist's dummy and chased a rogue haggis that was being pulled across the floor by a long piece of string.

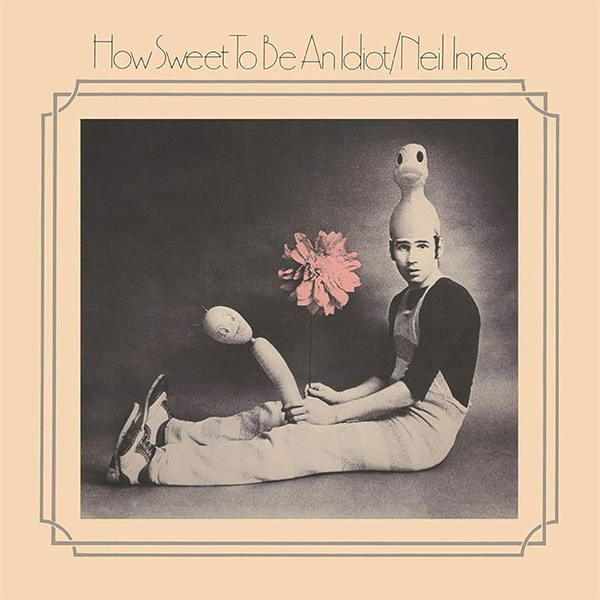

It was also during this period that Neil recorded his first solo album, How Sweet to Be an Idiot (1973), which contained such fine compositions as the cleverly catchy ballad Singing a Song is Easy, the Stevie Winwood-like Immortal Invisible and the New Orleans funk-styled Topless A-Go-Go, as well as a sweet love letter to his wife, Song for Yvonne ('If you were a song I'd sing you/But you're more than meets my eye').

The memorable title track, with its White Album-reminiscent melody and slyly smart lyrics (which included not only such elegantly evocative lines as the justly celebrated 'And dip my brain in joy' but also the joyously contrived rhyming couplet: 'Hey you, you're such a pedant/You got as much brain as a dead ant'), would not only be reprised the following year when Neil joined the Monty Python troupe for their live shows at Drury Lane, but would also be unofficially reprised by Oasis for their 1994 single Whatever (he would, eventually, be given a co-writing credit for the song).

Neil's working relationship with the Pythons had actually begun a little earlier, when they invited him to provide some music for their own albums Monty Python's Previous Record (1972) and The Monty Python Matching Tie and Handkerchief (1973), and the association would never really end. Aside from his contributions to their later TV series and his appearances with them on stage (where he not only had his own solo spot but would also join in with the odd sketch, such as his brief but always enjoyable turn in the Election Night routine as the leader of the Slightly Silly Party, Mr Kevin Phillips Bong), he would also write music for many of their collective and solo movie, record, TV and stage ventures over the subsequent years.

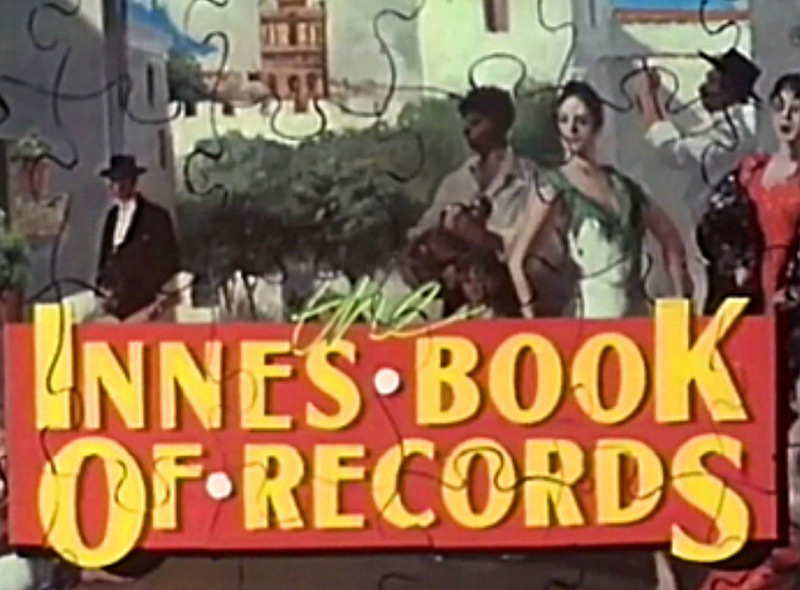

One of these would be Eric Idle's BBC Two sketch series Rutland Weekend Television (1975-6), which - with its quota of a couple of music videos per episode - provided him with such an excellent showcase for his compositions (such as Twenty-Four Hours in Tunbridge Wells, Protest Song - which was introduced with the ominous announcement: 'I've suffered for my music, and now it's your turn' - and L'Amour Perdu Cha Cha Cha), that it led to the commissioning of his own show, The Innes Book Of Records.

It had been Ian Keill, the producer/director of Rutland, who had pushed for the programme, having not only greatly enjoyed the experience of working with Neil on his 'lighter' songs but also having realised, from listening at leisure to his back catalogue, that there were so many more colours in his palette that could now help paint a broader range of pictures. Running for three series (and one-hundred-and-eight videos and songs) between 1979 and 1981, this remarkable solo show (one of the seeds, one might argue, of MTV amongst other things) would win him a relatively small but extremely loyal and appreciative weekly audience, as well as plenty of critical praise.

Once Neil had overcome his aversion to the show's title - he wanted to call it Parodies Lost - he loved the liberty that the format gave him to explore many of the themes and dreams which most intrigued him. Described by him as a show with 'songs and pictures, about people and things,' dipping your brain, this time around, in a sparkly mixture of sherbet and hundreds and thousands, it was, once again, a hit-and-miss viewing and listening and thinking experience, but that's what happens when one takes risks rather than avoids them, and, more importantly, there were far more hits than misses if one appreciated the constant criss-crossing of periods, paces, cultures, tastes, trends, genres, ideals and ideas.

In one scene he'd be performing an effortlessly effective Noel Cowardesque confection, in the next he'd be playing at not so much a Fifties' rock and roll routine as, folding one layer over another, a revivalist Fifties' rock and roll routine. In another scene he'd be dressed as Superman extolling Britain's seaside holiday camps, while in yet another he'd be posing as a satanic cabaret strip-club host in Soho. He also played Bob Nylon, a depressed busker, and Nobby Normal, the doyen of dullness, as well as Toulouse Lautrec, Tarzan, Captain Kirk, Marlene Dietrich, Batman, Charlie Chaplin, all of the Marx Brothers and Clint Eastwood. Guests such as Sir John Betjeman would be shown reclining in an armchair reading out one of his poems, while animal impersonator Percy Edwards would intrude on sentient flowers with some bird calls and John Cooper Clarke recited Evidently Chickentown from within a dull man's bathroom mirror.

Spawning two varied and treasurable albums - The Innes Book of Records (1979) and Off the Record (1982) - the show was destined to end up being remembered, in that bitter-sweet way, as a 'cult classic', but it was actually just a splendid body of work that merited a much broader audience than it was afforded. The official explanation for why (after one untrumpeted late-night reprise) it never received any further repeats was that, as so many ordinary members of the public had been featured for free without signing any of the formal clearance forms, there was no paper trail to track them down and collect all of the permissions for additional screenings, but, as time went on, the suspicion grew that it had considerably more to do with the Corporation's already-declining interest in preserving a place for the quirky.

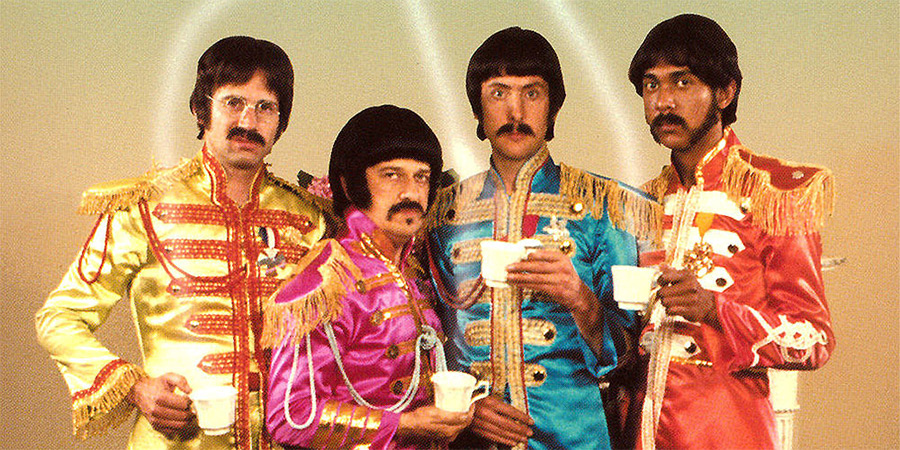

There was, however, another serendipitous spin-off from Neil's involvement in Rutland Weekend Television: The Rutles. Originally a brief one-off parody of the old black-and-white coverage of early-1960s Beatlemania, with Neil writing and performing a delightfully accurate and evocative homage to the band's early output, the sketch made such an impact that Lorne Michaels, the all-powerful producer of Saturday Night Live in the US, encouraged Idle and Innes to develop the conceit into a full-length TV movie about the Prefab Four. The resultant 'mockumentary', if you will, called All You Need Is Cash (1978), along with its soundtrack album, would be one of the true triumphs of Neil's career.

Although Eric Idle appeared on screen as the head-rolling McCartney doppelgänger Dirk McQuickly, on record he was replaced by Neil's great friend, the singer and guitarist Ollie Halsall (whose vocals were speeded up slightly to match Paul's pitch), while Neil himself continued in the role of Ron Nasty, and they were joined by the jovial Cambridge publican and internationally admired session drummer John Halsey (playing on Lou Reed's Walk on the Wild Side being one of his past gigs) in the Ringo role of Barry Wom, and Ricky Fataar (late of the Beach Boys) as the George-like character of Stig O'Hara (the bassist Andy Brown would also provide support). Spanning and echoing the whole of the real 'Fab' era, the aptness of every aspect of Neil's pastiches, from the grain of each voice to the polished precision of all the productions, was remarkable (even the few songs he entrusted to another vocalist - such as Living in Hope, sung with exquisite Ringo-like clodhopping charm by Halsey - sounded eerily effective).

It was not just on record that Neil excelled. His on-screen performance was also a satirical delight. There was one especially memorable scene - a send-up of John and Yoko's Bed for Peace events - that obliged Ron to sit in a bath directly under a shower, soaked but fully-clothed, next to his terrifying wife Chastity. As Yvonne recalls in her book, Neil's improvised response to an interviewer's question as to what kind of happening was happening - 'We're getting wet. In a shower. Because, basically, we talked it over, Chastity and meself, and we came to the conclusion that civilisation is nothing more than an effective sewage system. And so by the use of plumbing we hope to demonstrate this to the world' - made Eric Idle burst out laughing and the scene had to be re-shot several times more.

One of the most avid and vocal admirers of all things Rutles was George Harrison himself (who even had a cameo in the movie as a roving TV interviewer), and, partly as a consequence of that and earlier connections, he would also become one of the biggest fans, and best friends, of Neil Innes.

It helped that they had so much in common. Both had grown used to having their humility mistaken for inadequacy; both had grown tired of being urged to hop through all of the customary commercial hoops; both, as George once sang, were determined not to live a life that wasn't real; and both, as Neil's wife would put it, had become firmly fame-phobic.

Socialising frequently together at Friar Park, George's haven of a home in Henley (where the pair of them, along with Eric Idle, filmed the video for Crackerbox Palace), they would sit and strum ukuleles, sing old and funny songs, and roam around the gardens, smelling the roses, sitting among the rocks, sharing tales about what George called 'this cockamamie business' in which they found themselves, at least sometimes, still obliged to be.

George knew why Neil didn't fight more against the irony of being thought of as an unsung singer-songwriter ('Neil was always ambitious', Yvonne would say. 'He just didn't want to use his sharp elbows to get where he wanted to go'), but sometimes even he wished his friend wouldn't stay quite so much the quiet one. He was simply too good to seem a secret.

What, then, was it that made Neil Innes so impressive? It was a number of things.

One of them was his remarkable ear not only for construction but also for character, which enabled him to craft the kind of pitch-perfect parodies and pastiches that sometimes seemed not merely to be simulating a signature sound but also skewering a sensitive soul. It was as if he had searched out another songwriter's scrunched-up rejects, the ones in which their own particular weaknesses and excesses had been just a little too evident, and smoothed them back out for a play.

It was like hearing someone break into a brain, kick an idea around for a bit and then slip away again. Take, for example, his Leonard Cohen tease, Carry On, Melissa, which manages to be, in the fatigued tone in which it is delivered as well as the tired lines that are listed, such an artfully smart internal meditation on the 'long, long way' that the listener, as well as the ostensible subject, still has to go when Len allows himself to labour:

You flicker like a candle

In the soft and gentle breezes

Of a deep-sea diver's nightmare

In a broken tam o'shanterYou flutter like an eagle

In the corner of a jam jar

While the spinning wheel keeps turnin'

Like a boulevard decanterCarry On, Melissa, carry on,

There's a long, long way to go...

When it came to The Rutles, 'You're so pusillanimous, oh yeah/Nature's calling and I must go there' (a couplet in that tribute to overly-toiled tweeness entitled Another Day) was probably as cruel as Neil ever got as far as this kind of unnervingly intimate creative critique was concerned, and as its target, Paul McCartney, was also, essentially, a nice as well as talented man, it hurt rather more than Neil had intended. Most of the time, however, such as in the double-tracked, mic-kissed distorted, imposter syndrome scribbles of his Lennon parody Piggy in the Middle ('Bible punching heavyweight/Evangelistic boxing kangaroo/Orangutang and anaconda/Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse/Even Pluto too'), he is simply applauding from within the thing he not only understands entirely but also adores completely.

He was not, by any means, merely (as if what he did ever merited a word as modest as a 'merely') a preternaturally gifted channeler of other people's talents. He also wrote plenty of songs that allowed you to look through his own eyes, with his own manner and moods.

He could be pithily pertinent both as a political commentator - 'No matter who you vote for/The government always gets in' says in a few seconds what it's taken quite a few lumbering academic articles to say in far too many pages - and a socio-cultural one (see Three Piece Suite: 'Two armchairs and a sofa make our world complete'), as well as sweetly observant (such as in the motorway café-set love story Kenny and Liza: 'Watching their heads get bigger and smaller/Foolin' around with a spoon'), or simply sincere (such as in the contrite Cat's Don't Like the Rain: 'Well I know sometimes I've treated you so badly/And I'm sorry if I caused you any pain/But you know me by now/That's how I love you/Just as true as you know cats don't like the rain') or just endearingly silly (such as What Noise Annoys a Noisy Oyster: 'This is just a song about an oyster/Oysters are so slippery and wet/Oysters have a pearl amongst the moisture/And make the sort of noise you can't forget').

Wittgenstein (at least when he was not as sloshed as Schlegel) liked to say that the only reason he did philosophy, whenever he did it, was because 'I don't know my way about'. It was probably something similar with Neil and music and comedy. Together they were his ship and his sea, his compass and his map. Subverting society in song and humanising it with humour helped him to fathom what otherwise appeared coldly unfathomable about the world, and share his insights, and doubts, with us.

'He did a lot of "thinking about thinking"', his wife Yvonne would write about him, and it was that ability to flit from content to form and back again, to slip the quotation marks on and off like a joke pair of devilish horns, that enabled him to satirise without seeming superior, and focus on another's flaws without ever implying that he himself was infallible.

The sad thing is that his rewards for showing so much brilliance were so often so much smaller than he deserved. 'Look away, maybe someday/Greed will stand trial,' he once sang. 'But meanwhile/You're never alone at the bottom of the pile'. It was never quite that bad for him, but there were far too many times when, while he watched someone else's back, another knifed his.

The most farcically egregious of these many slights and setbacks occurred soon after the first flush of success enjoyed by The Rutles. ATV Music, which now controlled the publishing rights of much of Lennon and McCartney's output, suddenly stuck its snout in the air and sniffed the scent of some fresh profits. It made an aggressive legal claim that Neil's Rutles songs crossed the line into infringing the compositions he had pastiched.

Neil fought valiantly but, ultimately, in vain. Musicologists analysed the songs and determined that, while Neil had gone close to the edge, he had not breached the copyrights. The similarities that ATV cited were in the performances, arrangements and production elements of the recordings - which are not copyrightable and are quite different to music publishing rights which come down to crochets and quavers on sheet music.

There is, however, a huge difference between being right on manuscript paper and being right in legal briefs - and proving it in an American court of law. The decision on whether to fight or fold had not been Neil's alone, and his music publisher eventually caved under the pressure, fear and risk of an expensive trial. Neil was forced to surrender fifty per cent ownership of his Rutles songs and they thus ended up being credited as 'Lennon/McCartney/Innes' - thus losing Neil a fortune in hard-earned royalties. Then, adding to the insult, his own record company had the nerve to demand an extra album from him, on the grounds that the one with his Rutles compositions was now deemed to contain 'non-original' material.

'No other business gets away with stealing like the music business,' Neil lamented. 'Except banking'.

It would by no means be the last of his trials and troubles. In 1996, Archaeology, a new Rutles album (prompted by a suggestion from another friend, the impresario and longstanding fan of both the Fabs and the Prefabs, Martin Lewis) which had been designed as a tongue-in-cheek companion to The Beatles' Anthology trilogy, was more or less suffocated at birth after Eric Idle claimed ownership of the band's name, thus ensuing more spirit-sapping 'sue me, sue you blues'.

In 2004, Spamalot, Idle's 'lovingly ripped-off' musical version of Monty Python And The Holy Grail, began its long and hugely successful run on stage, only for Neil to discover that he was not (at least after a short while) receiving the royalties he was owed for his contributions. In 2014, when Idle (now deep into the period of what Neil called their 'mutual irritation') took charge of the set of highly lucrative Monty Python reunion shows at the O2 in London, Neil was devastated to discover, without any personal contact let alone an explanation from anyone involved, that he was not going to be invited to join his old friends one final time on stage.

As these and other unwarranted blows kept coming in, rather than stooping to the snake-like level of his abusers, he preferred to withdraw from the madness of it all, lick his wounds in private and then try his best to find far better people with whom to spend his time. He was, as he always put it, committed to being 'pro-good things and anti-bad things'.

Neil's principled default position, in relation to others, had always been, and would always remain, to trust. 'He trusted that people would pay him for work completed,' Yvonne would recall. 'He trusted that people he worked with would do the right thing. He expected fairness and was disappointed when he was proved wrong'.

Neil was not guilty of being naïve. Blaming someone for being naïve is how cowardly people excuse themselves for standing by and allowing cynicism to win.

Neil was only guilty of being good. The fault was with the bad guys, not with him. What a shame that they kept getting away with it, and what a shame that he had to suffer so much for it.

Honesty, fairness and integrity were things in which he still stubbornly believed, and, no matter how far down the road he travelled, nor how old he got, the absence or abuse of them never failed to shake him to the core. 'Alcohol or joints helped hugely,' Yvonne would say of how he tried to cope with the disappointment, 'but it was sometimes impossible to reach him, the hurt was so deep'.

Nothing, however, would ever stop him from doing what he wanted, and needed, to do. It might sometimes have been in smaller venues than he might have liked, and one or two times it might have been boosted with bigger budgets than he had expected, but, however the fortune flew or fell, he always seized the moment, and engaged happily and gratefully with whomever was there.

He continued working on the unusual things. There were several TV series for children (The Book Tower, 1985; Puddle Lane, 1985-8; The Raggy Dolls, 1986-94; East Of The Moon, 1988), a few Bonzos-related commemorations, various on-stage Rutles reunions, and a number of collaborations with his fellow comedian and musician John Dowie, such as the often-spikily funny Ego Warriors. There were also four instalments of an experimental aural memoir, called Radio Noir, which sadly proved even more incomplete than any autobiography is doomed to be.

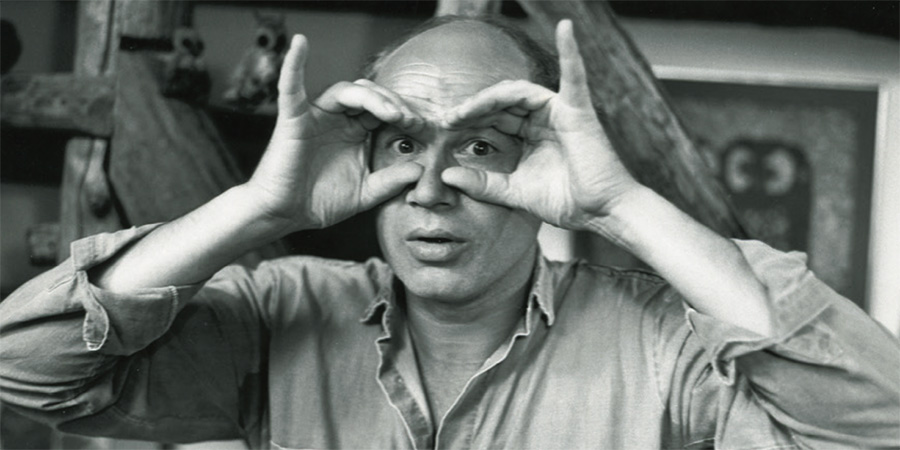

A documentary, entitled The Seventh Python, was released in 2008 to celebrate his career. Some of the most memorable of his later solo musical work were collected together for the 2014 compilation Neil Innes - Innes Own World: Both Best Bits. Neil was never, however, one to gaze far back, he was always looking forward, with that inimitable twinkle in his eye, and that priceless mischief in his smile.

'Oh my - nobody wants to die', he sang. 'But it can hit you right between the eyes...' Neil Innes passed away on 29th December 2019, from a heart attack, at the age of seventy-five.

Those lines came from what was most certainly one of the finest, and certainly most poignant, songs from his final few years, after he had lost so many of his own much-adored old allies: a tender elegy called Friends at the End (2005). Inspired, in part, from the experience of receiving the bad news, again and again, via the terrible and cold abruptness of a telephone call ('You put the phone down thinking "Oh God not another one"/Then close to tears, you selfishly begin to count up all the loved ones you have lost over the years/You try to picture their faces while there's something going on in the place where your stomach used to be/Then you realise it's the oldest and the coldest fear ever known to humanity...'), and sharpened into focus even more by the specially-keen and cruelly premature loss four years before of his dear friend George ('Here come all the suns/Here comes all the light...'), it captured all of his special warmth and sage realism:

Worn out shoes and rusty cars

We are all the stuff of stars

Sub-atomic carbon-based

Everything is made in space

As it was before your birth

Nothing lasts forever on earth.

As the song, then, mourned those who had been so dear to him, so it, now, mourns the man who was, and is, so dear to us. A friend, it felt like, to the end, and still a friend, in a way, to this day.

He once raged, late on in his life, at the sheer solipsistic callousness encouraged by modern culture. 'I call it cognitive stupidity,' he said. 'Just stop it. Do something sensible. We all know the writing's on the wall, the reality check is in the post. So let's all ease ourselves into something that could make us all happier'.

He was wearing a small rubber duck on his head when he said this - of course he was - and, if anything, it made his message even easier to accept and applaud. It is just a shame that, as usual, not enough people, at least back then, got to hear it.

'All through Neil's life,' reflected his wife Yvonne, 'there seemed to be something in the way of getting his work out to more people, to bigger audiences, spreading the word'.

There is no reason, however, why we can't still try to rectify this for the man who so many times managed to dip our hearts, as well as our brains, in joy. He deserves to be remembered. He deserves to be respected. He deserves to be enjoyed.

If you heard Neil Innes, if you saw him, if you thought about him, if you knew him, then you loved him. He was one of the most thoughtful, perceptive, distinctive, witty and wise artists of his time, but, even more important than any of that, he was good as well as great.

Neil Innes really was nice. Thank God for that.

And thank God for Neil Innes.

A Celebration of the life of Neil Innes takes place at indigo at The O2 on Thursday 28th November. Tickets

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreDip My Brain In Joy: A Life With Neil Innes: The Official Biography

'Some called him the seventh Python, but I prefer to think of him as the first Neil Innes' - Michael Palin.

Few individuals have had such an impact on British culture over the past fifty years as the comedy and music icon Neil Innes.

He was the songwriting powerhouse of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah band. Beatles muse and collaborator. Injector of art college surrealism into 1960s TV comedy. Instigator of a revolution that led directly to Monty Python, the group he repeatedly joined on screen and stage. He was Ron Nasty, co-founder of the much-loved Rutles, the 'pre-fab four'. Accidental inventor of the phrase 'Cool Britannia'. Much-loved children's TV storyteller, thinker, maker, creator, undisputed national treasure and Britain's sweet idiot laureate.

And through it all, Neil remained one of the kindest and brightest individuals in showbusiness. Musicians, comedians and fans alike loved being around Neil. He created music and joy and art wherever he went. And the person who loved having him round more than anybody else was Yvonne. Neil and Yvonne met at Goldsmiths College in the 1960s and they went on to walk hand-in-hand through life for over fifty years, until Neil's untimely death in 2019.

This book is a heartfelt, eyewitness tale of the life of one of British culture's quiet geniuses. It is tribute to life inside the circus, with the gentlest and wisest of clowns.

First published: Thursday 24th October 2024

- Publisher: Nine Eight Books

- Pages: 320

- Catalogue: 9781785121692

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Nine Eight Books

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Nine Eight Books

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.