The Mission of Miles Malleson

Britain's comedy character actors, often blessed with far more free time than those at the top of the bill, have pursued, over the years, some intriguing off-screen interests. Beryl Reid, for example, who appeared in everything from Educating Archie on the radio to Entertaining Mr Sloane at the movies, was an obsessive collector of over-sized novelty earrings and medium-sized stray cats; Deryck Guyler (a stalwart of such shows as ITMA, Sykes and Please Sir!) amassed a collection of ten thousand toy soldiers, mastered the washboard as a musical instrument and was a devoted student of the Bible; and James Robertson Justice (the bearded, booming, boorish boss in so many old British comedies) had a particular passion for falconry.

Then there was Miles Malleson. Miles Malleson was different - very different.

He took his own extra-curricular activities up to another level entirely. He devoted much of his spare time striving for the complete and utter collapse of international capitalism.

There is, of course, no getting away from the fact that Miles Malleson is now regarded as one of those seemingly dim and distant 'I wasn't even born then' figures, like Andrew Bonar Law, Demosthenes, Little Tich or Jesus, but, if you have watched any old British comedies originating from the 1940s through to the 1960s, you are probably far more familiar with him than you might initially have thought. The man seemed to be everywhere, and, no matter how slight and small his role might have been, even if you blinked you never missed him.

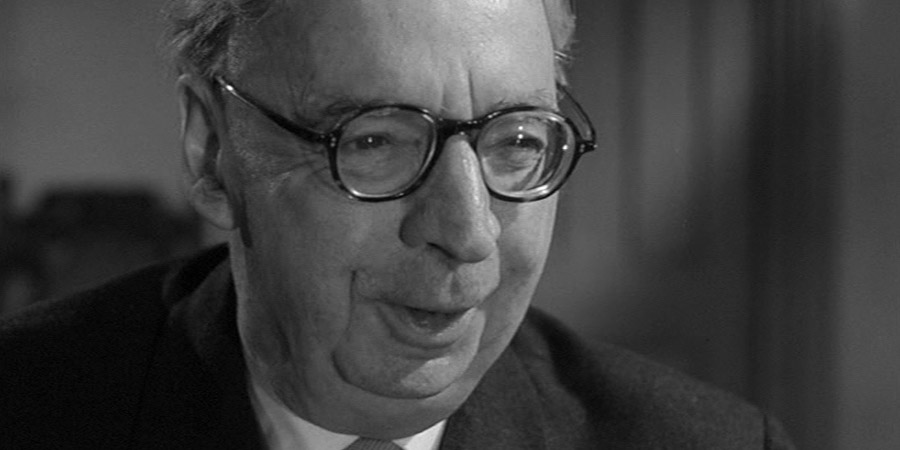

First there was his face: the aimlessly undulating forehead; the chronically astonished eyebrows; the bright, slightly slanting, sheep-like eyes; the overly-tweaked ears; the long, sharp, snooping nose; the modest mouse hole of a mouth, with the thick lower lip jutting out like a small but well-scrubbed welcome mat; and the delicate nest of receding chins, wobbling gently like a whirl of whipped cream, which caused him to tilt his head slightly back as if to stop them from slipping down his neck. It was an extraordinary face, and an implausible face - as though various discrete samples for a contrasting range of countenances had all been tossed carelessly together on to a single canvas, leaving him looking like a cross between a deeply confusing police photo-fit picture and a disarmingly homely hobgoblin.

Then there was his body: tall and slender-shouldered but, given the arch-backed, barrister-like nature of his posture, it was adorned by a tummy that thrust out so that it seemed far plumper and contentedly post-prandial than it actually ever was. It gave him a slightly swaying, waddling gait that one critic likened to that of 'a tired duck'.

Then there was his voice: a light, reedy, hurriedly eager-to-please sort of sound, but with the occasional swoop down to a richer, warmer, fruitier pitch when responding to something unusually promising or pleasurable, such as the prospect of a rare adventure or the proffering of a glass of port.

All of this added up to a near-perfect cluster of curious human qualities. If you needed someone to lend an air of English oddity to your comedy, Miles Malleson was top of your list.

He knew exactly what he was doing. 'The actor's craft is founded on real interest in people,' he once said. 'There are two things to remember in creating a character: how a man looks and how he feels.' All of his performances were driven by that dialectic.

He could turn the stereotypical into something believable; he could make the implausibly idiosyncratic appear intriguingly organic. As one critic put it: 'His nitwits had souls as well as stupidities.'

He was rarely afforded more than a few minutes in most of his movies, but, thanks to his exceptional scene-stealing abilities, a few minutes was all that he needed to make his presence felt. He was probably the best and most artful scene-stealer in British cinema for a couple of decades or so: hand him a role that required him merely to sit still and listen, or wander from one end of a shop to the other, or mutter something while picking up a book, looking at it, and then putting it back down again, and Miles Malleson had the guile to turn it into one of the most memorable moments of the movie.

In Kind Hearts And Coronets (1949), for example, he only has two brief scenes, but they are two of the best-remembered. He is the first figure one sees: the hangman, Mr Elliott, a creepy, creeping, forelock-tugging snob so excited at the prospect of dispatching a duke that he cannot envisage any way to top such a dubious achievement ('I intend to retire,' he announces solemnly. 'After using the silken rope...never again be content with hemp'). He returns at the end of the movie, having long waited for his moment, to read out some of his depressing doggerel to the soon-to-be-departed duke ('While yet of mortal breath some span...however short, is left to thee...'), and, inadvertently, to twist the plot another touch. The last we see of him, brusquely fleeced by fate, he is stranded alone in the cell, his mouth opening and shutting helplessly like a goldfish plucked out of a pond.

In The Importance Of Being Earnest (1952), he gives a deliciously mischievous performance as the sunny-natured, straw-hatted Canon Chasuble, a simple country vicar 'peculiarly susceptible to draughts,' who struggles to disguise his lusty desire for the prim Miss Prism via a succession of alarmingly febrile figures of speech ('Were I fortunate enough to be Miss Prism's pupil, I would hang upon her lips... I spoke metaphorically. My metaphor was drawn from bees').

In Private's Progress (1956), he popped up again as an easily-distracted author, hiding away from the world behind a wall of old books. Waffling away about his work on the history of music hall songs, such as Boiled Beef and Carrots, he stuffs his pipe assiduously, mutters absent-mindedly to his son, Stanley, about the wife who 'disappeared' some time ago, and shakes his head sadly about the 'seedy crowd' with whom his daughter now seems to be mixing. Malleson only had a few minutes on camera, but he was crafty enough to ensure that what he did, by embodying an endearing idea of old-fashioned English dottiness, would be far more memorable than the script might originally have suggested.

He then reprised the role in I'm All Right Jack (1959). Although limited to a similarly small amount of screen time, he had no need on this occasion to resort to any scene-stealing tricks, as his character was now a contented resident of 'Sunnyglades Nature Camp,' and was shown sitting happily in the garden, stark naked, with only an earthenware bowl to cover his modesty as he washes a succession of mushrooms. He is still much the same, however: a little worldlier, perhaps ('That's our Miss Forsdyke. Not a natural blonde, of course'), but generally he is simply happy to hide away from harsh modernity in his own nostalgic niche: 'It's simply a question of attitude,' he tells his socially unsettled son. 'Here we're down to fundamentals. Dignity and privacy, Stanley, only exist nowadays in a place like this.'

He was just as slyly diverting acting opposite Terry-Thomas, as another character locked away in the memory of a kinder, gentler time, in Carlton-Browne Of The F.O. (1959). Playing Davidson, the half-forgotten resident adviser happily stranded on a former British colony, he is found by the newly-arrived emissary from the Foreign Office dozing like a dormouse on a dusty old chaise-longue, with one foot propped up and plastered like an over-blown balloon. Once woken, he babbles away to them about a mysterious hole-digging exercise that is going on all over the island ('They never stop. They're like moles!') until the penny finally drops that they are speaking to someone for whom the clocks have long since stopped ticking.

He then gave yet another effortlessly eye-catching cameo performance in the Peter Sellers vehicle Heavens Above! (1963). On this occasion he played a hapless old psychiatrist called Rockeby, an 'expert' so wrapped-up in his own cloistered little world that, when called on to venture out and assess a particular patient, he is so disoriented that he ends up analysing the wrong person. 'Most interesting,' he mutters in a dazed way as he heads off home again.

This, then, was the Miles Malleson that the public had come to feel that they knew: a comforting icon, in a fast-changing post-war world, of the kind of harmless and timeless eccentricity that the country still liked to consider a natural ingredient of its fondest form of freedom. It would have been quite a shock to most of his admirers, therefore, if they had known that the man so closely-associated with such a conservative cultural vision was, away from the screen, a committed communist.

It is actually not that surprising that Miles Malleson grew up to be a communist, because he came from a family rooted firmly in radical soil. His grandfather, for example, was William Taylor Malleson, who had been at the forefront of countless progressive political campaigns in the nineteenth century, and was a close friend and supporter not only of John Stuart Mill (one of Britain's prime modernisers of liberalism as well as its most eminent male campaigner for women's rights), but also Thomas Hill Green (who, more than anyone else at the time, paved the way intellectually for the establishment of, among other welfare-oriented institutions, state schools, the BBC and the NHS) and Giuseppe Mazzini (who was leading the revolutionary movement for the unification and independence of Italy).

Young Miles, however, soon moved far beyond the committed but conventional reformism of his forebears. Educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he studied History and co-founded (along with his best friend of the time, the poet Rupert Brooke) the drama-based Marlowe Society, he was driven by what one of his contemporaries would describe as a kind of 'Shelleyan idealism', devouring all the radical writings he could find (including those by John Cartwright, Thomas Paine, Saint-Simon, Fourier, Proudhon, Bakunin, William Morris, Robert Owen and Karl Marx), and started acquiring an increasingly wide range of left wing friends and mentors (among whom would one day be Ramsay MacDonald, Britain's first socialist Prime Minister, and Léon Blum, France's first socialist Premier).

Encouraged especially by the radical politician (and Cambridge contemporary) Clifford Allen, he would go on to join the Independent Labour Party (the predecessor, and subsequently the more aggressively socialist affiliate, of the Labour Party) as well as the campaigning pacifist organisation, the No-Conscription Fellowship. Throwing himself into the world of progressive politics, he wrote several anti-war and anti-establishment plays and pamphlets (several of which were seized by police under the Defence of the Realm Act), gave numerous talks to local socialist and communist groups, and celebrated the Bolshevik Revolution by co-founding the 1917 Club in Soho.

He was by this stage far more of a communist than a socialist by conviction. Although he would never be a card-carrying member of the notoriously dogmatic British Communist Party, he was a very enthusiastic fellow traveller, and was quite open about his strong desire to see his own country become a state-withered society of free and equal citizens, operating according to the basic Marxist principle of 'from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs'.

There is no doubt that Malleson was sincere about all of this. While by no means a sophisticated political thinker, he was nonetheless a passionate one, and he worked long and hard as a propagandist.

In 1925, he agreed to serve as National Director of the Independent Labour Party's newly-formed Arts Guild, an organisation set up to spearhead 'a revolt against the ugliness and monotony of modern industrialism' and encourage the transformation of society in accordance with the ideals of 'beauty and a fuller life'. Travelling hundreds of miles around the country each year, as a self-proclaimed 'missionary' for his communist cause, he sought to mobilise support in the most impoverished working class areas, set up local politically-inspired education and drama groups, establish touring companies, and utilise a repertoire of powerful but accessible left-wing plays designed to engage with the heart as well as the head.

The main reason why a revolution had not yet happened in Britain, Malleson argued, was 'largely because the mass of people are ignorant of the facts of the society in which they live'. It was this ignorance, he asserted, which drama could help to dispel. He thus became, for quite a few years, the country's most important left wing cultural conduit, linking party activists with all of those writers, actors, directors and producers who were sympathetic to socialist and/or communist aims and ideals.

In 1934, he accepted an invitation from the Trades Union Congress to collaborate with Harry Brooks (a Labour activist railway signalman from Poole) to write a play, Six Men of Dorset, that commemorated the centenary of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. It was performed for the first time at the Dorchester Corn Exchange, with the red flag flying high outside, and was then staged again by the TUC for an audience of international socialist delegates - which would make Malleson much better known as a left-wing figure in numerous other countries.

He visited the Soviet Union on several occasions as a special guest, where he was always kept well away from 'ordinary' citizens and treated to a succession of VIP trips to the theatre, where he was impressed by productions of King Lear, Pygmalion and Dombey and Son. By now too often distracted by acting to maintain a fixed focus as an activist, he seemed easily dazzled by whatever propaganda was proffered, and did not appear to need any pressure to keep toeing the party line.

In 1952, after joining a number of other British radicals on a six-week tour of the relatively newly-established People's Republic of China (a visit that was carefully choreographed and controlled by CPC officials to avoid any hint of the many abuses of state power, the strict regimentation of social life and the increasingly brutal oppression of intellectuals that would otherwise have been all-too apparent), a bright-eyed Malleson arrived back in Britain eager to spread the word about the 'exciting' and 'democratic' new regime. In an unfortunate, but rather telling, echo of Sidney and Beatrice Webb's exercise in useful idiocy, when they returned from a similarly selective visit to Stalin's Russia in the 1930s and declared that they had 'seen the future and it works', Malleson proceeded to give a number of talks around the country to left-wing groups, waxing lyrical about how all Chinese people were 'solidly behind' the leadership of Chairman Mao, and what an 'unshakeable and united' new social system was in the process of construction. He concluded by insisting that 'there is more happiness to the square inch [in China] than there is anywhere else in the world'.

He also wrote a deeply idealistic, very effusive but in places rather moving twelve-page pamphlet - An Actor Visits China - about his experiences for the Britain-China Friendship Association (which at the time was listed by the Labour Party as a 'proscribed organisation'). The text concluded by declaring that the Chinese brand of communism, much like the Russian one, was seriously misunderstood by the West:

There is an Iron Curtain and a Bamboo Curtain. But they are not so much Curtains as mist to be dispelled. It is a great mist heavy with fear, hate, suspicion, ignorance, misunderstanding, prejudice; but a fresh wind of good-will, knowledge, courage and understanding could blow it all away. And when that happens there will be a new light in the world. Every local and national culture will be influenced and enriched by every other; and all the peoples of the world will be able to enjoy the finest things that the human spirit has to give.

He would remain just as happy to parrot Mao's many opportunistic manipulations of Marxism during the subsequent 'Great Leap Forward', somehow managing to ignore or dismiss all of the sobering reports of famine, violence and torture that were now being smuggled out of the country. Like one of his Panglossian comedy characters, he seemed content to smile and pat his hands together and assure his audiences that all would soon be well.

One of the side effects of these alarmingly naïve encomia was that Malleson - already monitored by security services in both the UK and the US - was now placed under even closer surveillance for his political beliefs and activities. It meant that, for all the cosiness of his on-screen characterisations, he was, by this stage, quite a dangerous man to know.

He had already been barred unofficially from working in America since the late 1940s, when Senator Joseph McCarthy's cynical campaign against real and imagined left wing 'subversives' was launched. Now, however, his many positive comments about the regimes in Russia and China caused additional problems not only for him but also for anyone thought to be associated with him.

A number of Hollywood and Broadway figures who had worked, or been known to have socialised, with Malleson (such as the actor Marjorie Nelson, the producer Peter Lawrence and the author and journalist James Aldridge) were hauled before the House Un-American Activities Committee at least in part because of that tenuous connection (and even one of his own sons, Nicky Malleson, was only admitted to study at Yale after being forced to swear that he despised his father's beliefs and promised to keep his distance from him in future). In particular, his very active and vocal participation in various campaigns during the early fifties to save Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the American couple who were eventually convicted of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union, made him one of countless convenient names with which to compromise a suspected communist.

Undeterred, and largely excused, Malleson took to socialising on a regular basis with those banished by Hollywood who were now based in England, such as the screenwriters Carl Foreman, Donald Ogden Stewart, Frank Tarloff, Ian McLellan Hunter, Howard E. Koch and Ring Lardner Jr; the directors Joseph Losey, Cy Endfield and Bernard Vorhaus; the singer Paul Robeson; and fellow actors such as Sam Wanamaker, Lloyd Bridges and Phil Brown. He even found occasional, but much-needed, work on television thanks to his association with Hannah Weinstein, a New York Jewish producer (considered by the FBI to be a 'concealed communist') who had fled America before she could be formally blacklisted, and was now overseeing such popular and populist British series (often written by her fellow left-wing exiles) as The Adventures of Robin Hood (1955-9) and The Buccaneers (1956).

He also joined many of these figures, along with the likes of his old friends Bertrand Russell, Michael Foot and Fenner Brockway, to help found, fund and promote the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Malleson threw himself into this cause with all of his customary conviction, writing supportive letters to the newspapers, attending rallies, giving speeches and organising benefit events, as well as taking part in the annual Aldermaston Marches. Now entering into his seventies, he seemed more ideologically engaged than ever.

MI5, however, remained relatively unconcerned about all of Malleson's many political activities, largely because they knew that, should he ever threaten to become a 'problem', they could always exploit the Achilles heel that was his other off-screen obsession: sex.

Miles Malleson was considered to be, to put it bluntly, a sex pest, and, therefore, a scandal waiting to happen.

An enthusiastic advocate of free love from his late teenage years onwards, he had explored the subject in some of his early plays, such as The Fanatics (1927) - a drama (dubbed by one critic 'the sensation of the season') about love, lust, liberty and experimental marriages which became the first ever play in London to feature a woman stripping off on the stage. He also explored the principle in his own personal life, not only having many affairs during his three marriages but also sometimes actively encouraging his wives to do the same ('In the way that some people keep open house,' Aldous Huxley once remarked acidly, 'the Mallesons keep open bed').

The bisexual film critic Nerina Shute, who hero-worshipped him during her twenties as 'the mouthpiece of young England,' would recall the many evenings when Malleson would turn up at the glamorous London apartments of various notable socialites, sit on the floor with a large glass of wine cradled in his hand and proceed to hold court on the subject of sex, talking on and on 'like an irritated angel' as he implored everyone present to abandon bourgeois morality and be motivated only by authentic desire. 'He seemed to think,' she reflected, 'that men and women should be popped into bed like cakes in an oven.'

As time went on, however, Malleson's attitude came to be questioned by some of his more conventionally-minded colleagues, who felt that he was serving his own concupiscence rather more earnestly than he was seeking someone else's consent. Sure enough, the number of complaints increased as his sexual interests started to intrude upon his professional relationships, and he had to be cautioned about his conduct on at least a couple of occasions.

His behaviour grew far worse, and more recklessly indiscriminate, in the latter part of his life and career. Although an unlikely-looking roué - this was a man who would wear a stage toupee on top of his own toupee - his appetite for sexual adventures never came close to being sated.

Young female performers grew used to expecting, and evading, his lascivious overtures from the start to the finish of each production with which he was involved. On one particular occasion at the 1959 Edinburgh Festival, when Judi Dench and Maggie Smith were appearing together alongside Malleson in a Restoration comedy called The Double Dealer, the pair of them ended up locking themselves in the lavatories between the matinée and evening performances in order to avoid his unwelcome but persistent advances ('He was always after us,' Dame Judi later confirmed).

It remains a matter for speculation as to whether or not the director Michael Powell was deliberately making a cheeky allusion to Malleson's in-house notoriety by casting him in Peeping Tom (1960) as the unnamed shifty-looking gent in search of pornographic pictures ('I'm told by a friend that you have some "views" for sale...'), but many of his contemporaries were certainly quick to make the real-life connection. Playing a 'dirty old man' on the screen when he was already being called that, and worse, backstage at theatres and behind the scenes on film sets, seemed a particularly shameless case of someone hiding in plain sight.

Somehow or other, however, he got away with it. Although the red top Sunday tabloids had accumulated more than enough incriminating material for a major exposé of his many sexual misdemeanours, they chose to hold back, and he would reach the end of his life in 1969, aged eighty, with his professional reputation intact.

It would almost certainly have been different, however, had his revolutionary ambitions been pursued a little more actively and directly, and perhaps, by this time, he knew this himself. While his own investment in the movement was now mainly limited to words rather than deeds, he still lived to witness, from a distance, the rise of the New Left in Britain and America, the Cultural Revolution in China, and the student revolts in Paris during May 1968, and, not always consistently but well-meaningly, he warmly embraced, discussed and applauded them all.

When he died, however, it was as if his political life had been buried with him. It was either ignored, or expunged, by his newspaper obituarists, who concentrated solely on his stage and screen career. Described only as an 'actor and dramatist', he was, it was said, 'one of the country's best-loved performers', as well as a 'great clown' and a 'comedian of originality'. Not even any of the constituent elements of that maddening ragbag of sects, sentiments and strategies known collectively as Britain's 'labour movement' bothered to honour him publicly for all of the work that he did, for so many years, on their behalf.

It was as if Miles Malleson's own complex sense of self had been simplified to the kind of amiably solipsistic old cove that he had played so often on the stage and screen. That was a shame. He did not just act and write, nor interpret the world in various ways. He also tried to change it.

The irony was that it ended up changing him - at least in the way that it managed his memory.

It is high time that this revisionism was reversed. Miles Malleson remains a man of note for what he did during his day job, but he is just as interesting, if not more so, for what he got up to in his spare time.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more