There's two of 'em! - The Winters and their discontent

As comic put-downs go, it could not have been more savage: 'If you hadn't been comedians,' Morecambe & Wise were asked, 'what would you have been?' Eric Morecambe, without missing a beat, answered: 'Mike and Bernie Winters'.

There was also, of course, the infamous reaction of the ordinary paying public, at the Glasgow Empire during their early years working the circuit, when, after Mike Winters had already been straining their patience for some time, he was joined belatedly on stage by brother Bernie. 'Aw Christ,' groaned one Scot from high up in the gods, 'there's TWO of 'em!'

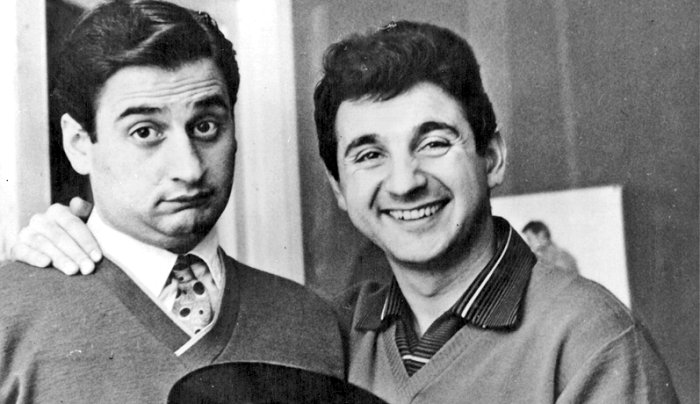

This is how Mike and Bernie Winters, if they are remembered at all these days, tend to be remembered: as the butt of better double acts' gags, and the bullseye that hecklers hit. Rarely analysed and seldom reflected upon, their career now serves merely as a conveniently stark contrast to that of Morecambe and Wise, the low that helps define the high.

Not all of this is unfair, but some of it is. While it is true that, in some ways, they did not help themselves (Mike, for example, strolled through the Swinging Sixties still smoking a pipe, playing the clarinet and sticking to the cold and clipped straight man template more suited to the American acts of a decade or so before, while Bernie gurned, gabbled and beamed his goofy grin like an old music hall droll, and both of them were far too tolerant of the substandard scripts they were given), it is also a fact that Mike and Bernie Winters achieved too much success to merit such a brusque and brutal dismissal.

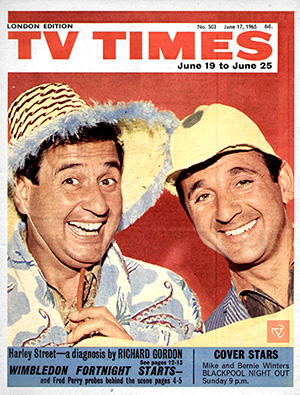

Their work together spanned four decades, reaching a peak in the mid-1960s when they were, without any doubt, one of the biggest comedy acts on British TV, starring in shows that were watched every week by many millions of people. Yes, they stayed in the shadow of Morecambe & Wise, but what a shadow that was.

They were never, in any sense, failures. They were simply never close to being the best.

There seem to be a number of reasons, when one looks back over the course of their career, as to why they never quite made it to the first rank of comedy double acts. One is the fact that they had neither the precision of purpose, nor the passion of pursuit, to match the progress of their main rivals.

The first ten years or so of their shared career in show business were interrupted frequently by bouts of self-doubt. Born Mike (in 1926) and Bernie (in 1930) Weinstein to a Russian-Jewish family in Islington, North London, they grew up wanting to be musicians rather than comedians, and both of them, as teenagers, played in the same dance bands (Mike with the clarinet and Bernie the drums).

It was only when their occasional banter in between songs started getting some laughs that they were tempted to try their luck as a double act, copying American duos like Abbott & Costello but without much success. They broke up for the first time following a few poorly-received gigs in the south-east, with Mike setting himself up in the stocking trade and Bernie (after an ill-starred attempt at a solo act doing little more than imitating Jerry Lewis) joining him belatedly as a salesman.

Once that particular enterprise collapsed shortly after the end of the Second World War (thanks to a combination of burnt-down factories, brusque interventions from the Board of Trade and an ill-managed move into mail order), they decided, for want of any other viable ideas, to revive the double act. They started getting gigs again at minor London night clubs, and appeared on stage supporting the likes of Benny Hill, Max Miller and George Formby (the last of whom disliked them so much he would make a point of glowering at them from the wings), and even made their debut on TV (on 25th June 1955) in the BBC show Variety Parade, but, by their own later admission, they remained a heavily derivative and unimaginative act.

They were once again thinking of giving up after their first major summer season - supporting Albert Modley at the Palace Theatre, Blackpool, in 1956 - flopped spectacularly badly ('We went twenty weeks without a laugh,' Bernie would lament), and only stopped considering splitting after (much to their surprise) they were chosen in March of the following year by the producer Jack Good (who had seen them perform on the same bill as the singer and teen idol Tommy Steele) to be the resident comics on the BBC's youth-oriented popular music show Six-Five Special.

The exposure afforded by that year-long association would have ensured that they continued to get regular engagements into the start of the 1960s, but even then their progress was once again disrupted when Bernie, quite suddenly and much to Mike's surprise and irritation, decided to attempt to make it on his own in movies (he was put under contract by the producer Cubby Broccoli). That strange little adventure soon ended in failure (with a minor straight role in the crime drama Johnny Nobody in 1961), and, somewhat awkwardly at first, the partnership was resumed.

In 1962 an unlikely opportunity arose for both of them to make a movie, when a young and inexperienced Michael Winner added them to the cast of his cheap and cheerless 'adaptation' of the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta The Mikado, called The Cool Mikado, alongside the likes of Frankie Howerd and Tommy Cooper. Treated like cattle by the deluded director (who addressed them with antiquated Hollywood grandness via an antique megaphone), and fed the corniest of lines (many of them written, at the last minute, by Winner himself), the experience turned out to be a miserable one for Bernie, who threatened on more than one occasion to put one of his catchphrases into action and smash Winner's face in, and an humiliating one for Mike, who only discovered that all of his lines had ended up being dubbed by a high-pitched American when he was watching the debacle at his local cinema.

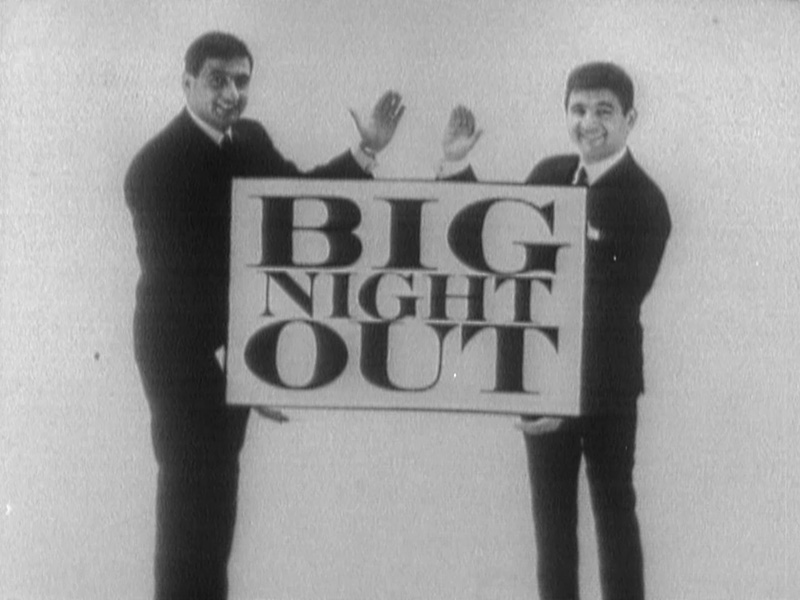

It was only when the well-respected ITV producer/director Philip Jones saw and liked them in a summer season-themed ABC variety show called Holiday Town Parade that someone felt inclined to give them their own peak time Saturday night variety show. The action-packed, guest-heavy and trend-friendly Big Night Out, which began (as far as their input was concerned) in 1963, would bring Mike and Bernie to millions of people and establish them as stars, but even then the pair seemed, behind the scenes, strangely diffident about their career.

Both of them, by this time, were married (Mike to Cassie, a former artist, and Bernie to Siggi, a German-born dancer) with children (Mike, so far, had a daughter, Bernie a son), and, now in their thirties, they may well have felt somewhat awkward about being marketed as the double act, as one tabloid put it, 'in tune with today's youth'. Neither of them appeared to know what to do with their new-found fame other than to make the most of it while they still could.

Brad Ashton, who (along with John Morley) would write for them for many years, would recall how, at the start of his relationship with the pair, a nervous Bernie Winters said to him, 'Brad, would you stick with us for a bit? I think we've probably got about two more years in the business'. That was in 1963. 'They really didn't think they'd last,' Ashton recalled, 'and this was just when they'd got their big break.'

It was, perhaps, a consequence of this short-term outlook that, while Morecambe & Wise would keep growing more active creatively, the Winters brothers would remain, essentially, passive. When, for example, Eric and Ernie were given what they regarded as sub-standard material by their then-writers, Dick Hills and Sid Green (and that happened on a fairly regular basis), they would not hesitate first to urge their colleagues to come up with something better or, failing that, to come up with something better themselves.

Mike and Bernie were far more submissive. When they were given material that they found uninspiring, they tended to shrug their shoulders, sigh, and start labouring long and hard to make it work as well as could be expected.

It is also important to note that, again in stark contrast to Morecambe & Wise (who would be encouraged more and more to master every aspect of their stagecraft as well as their material), Mike and Bernie, as they embarked on their years of stardom, were not only handed barely any time for rehearsal, but were also obliged to make many of their shows either live or 'as live'. The result was that, as Eric and Ernie (who were afforded increasingly lengthy periods of time in which to prepare) would look increasingly polished and professional, Mike and Bernie seemed to stay slapdash and amateurish.

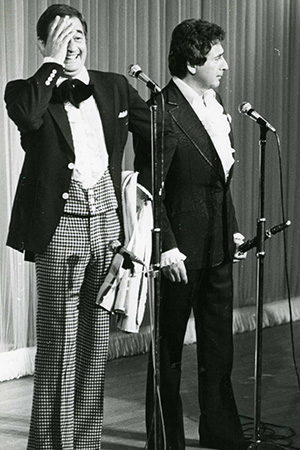

Cues would be missed, lines misremembered, sets wobbled and props malfunctioned. On one occasion, Bernie was supposed to start the show by playing a secret agent who departed his boss's office carrying a briefcase full of dynamite, and then, after the sound of a loud 'Boom', come crashing back through a wall covered in plaster, shouting: 'Good evening, everybody - welcome to Big Night Out!' Unfortunately for him, the set-makers had rendered the wall rather more robust than required, causing Bernie to become wedged halfway through it, bleeding from multiple cuts to his arms and legs. Stagehands had to extricate him swiftly from the wreckage, while a nurse covered his wounds, so that he was ready to return on time for the second sketch.

On another occasion, during a Western spoof, Mike was meant to hit Bernie over the head with a bottle of beer, which had been specially 'scored' so that it would snap in half on impact. Someone, however, had forgotten to score the bottle, and so Bernie, who was knocked to the floor, ended up having to stagger through the rest of the show in a state of mild concussion.

The pair of them, sporting the kind of rictus grins that greeted the presence of panic, would have to rely on their charm - and they did, especially Bernie, have a fair amount of charm - to steer them through each one of these on-camera crises. It suited the show, which thrived on projecting a 'flying by the seat of the pants' aura of real or supposed spontaneity, and it exploited the strengths, and weaknesses, of its hosts.

'Bernie always had a problem learning and remembering lines,' Brad Ashton would recall. 'That's why he ad-libbed so much - he had to: he couldn't remember what he was supposed to be saying! Mike did know both their lines, so he was able to let Bernie ad-lib and then bring him back to the script. So few routines played out as they were meant to, but, most of the time, they still ended up being funny.'

They also lacked the brilliant production team (and the degree of executive-level indulgence) that would help to make Morecambe & Wise, once they settled at the BBC, climb the heights. Eddie Braben ('never a great admirer,' as he put it politely, of Mike and Bernie's material) did not just write excellent comic scripts for Eric and Ernie; he also played a key role in re-shaping their relationship for the screen, writing for characters rather than just comedians. The richness, the variety and the overall quality of their shows also owed much to the invention and perfectionism of their producer/directors, John Ammonds and Ernest Maxin.

Mike and Bernie, although they worked with some decent directors, never had anything approaching this level of commitment, care and expertise behind them. Morecambe & Wise were pushed to keep upping their efforts; Mike and Bernie were allowed to coast. In the musical terms of the time, Morecambe & Wise matured into an album band, while Mike and Bernie Winters remained a singles act.

The Big Night Out shows, nonetheless, continued to command huge audiences throughout their two-year run, as did (even more so) the series that succeeded them: Blackpool Night Out (1964-5). One sign of their commercial clout during this decade was the fact that The Beatles (who appeared once with Eric and Ernie) were Mike and Bernie's guests on no fewer than three occasions (and Paul McCartney's affectionate echo of Bernie's catchphrase, 'you little choochy-face', in relation to Ringo, three decades later at the end of their Anthology TV series, showed how fondly they remembered these experiences).

The star guests kept on coming: Diana Dors; Bob Monkhouse; Eartha Kitt; Des O'Connor; Peggy Lee; Cliff Richard; Shirley Bassey; Ronnie Corbett; Petula Clark; Frankie Howerd; Chita Rivera; Adam Faith; Cilla Black; Tommy Cooper; Lulu; Georgie Fame; Susan Maughan; Sophie Tucker; Buddy Greco; Dusty Springfield; numerous other pop acts, countless comedians and some major international performers, too. It was just what ITV wanted, and the hosts helped make it all work with a huge amount of energy, plenty of self-effacing humour and a playful kind of pragmatism.

Mike Winters would later somewhat exaggerate when he claimed (in his memoir The Sunny Side Of Winters) that 'although Eric and Ernie's show was far better received by the press, Big Night Out dominated the ratings' - the reality was that both vehicles usually attracted audiences quite similar in size - but it was certainly true that Mike and Bernie held their own - not only on TV but also in the annual circuit of high profile pantomimes and summer seasons - in the ongoing battle of the double acts.

Ultimately, however, the effectiveness of their own partnership was undermined by the oddest reason of all: namely, that Eric and Ernie seemed more like siblings than Mike and Bernie ever did. We can actually be more specific than that: Eric and Ernie came much closer to matching the idea of brothers many of us have in our dreams, whereas Mike and Bernie remained more like the idea of brothers some of us have in our nightmares, or, in some unfortunate cases, in our actual lives.

Eric and Ernie clearly liked, admired and respected each other; indeed, deep down, they seemed to love each other. Mike and Bernie, in contrast, seemed, at times, merely to tolerate each other. Morecambe & Wise's was a relationship that radiated warmth. Mike and Bernie Winters wafted more of an unseasonal chill.

Although the two double acts would remain rivals throughout the Sixties, providing mainstream British comedy with a conveniently neat North/South divide in terms both of style and sensibility, the Seventies would see Morecambe & Wise accelerate off into the distance while Mike & Bernie Winters spluttered and stalled. The former found another level that the latter simply lacked.

One might have expected ITV, once it lost Morecambe & Wise to the BBC in 1968, to have responded by pouring far more money, effort and imagination into promoting the double act that remained on its books, but, in practice, it seemed too disenchanted, or distracted, to fight back. Mike and Bernie were allowed to fall out of fashion, offered nothing other than 'more of the same' sorts of vehicles, on lower budgets and featuring older, less exciting, guests.

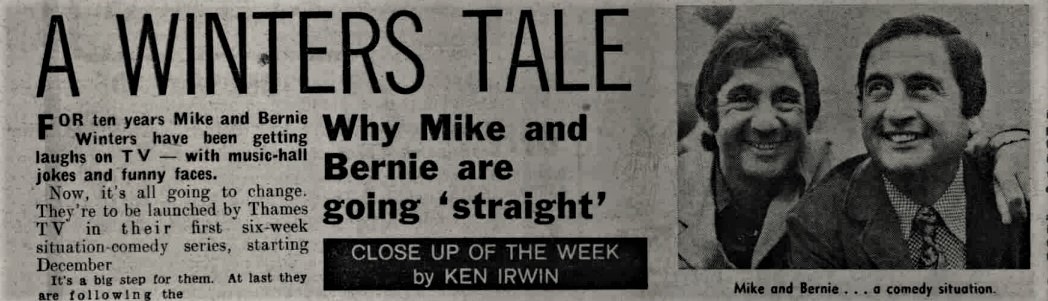

They did begin the new decade with something that was at least superficially novel: Mike And Bernie's Scene (1970), a show that promised to have 'a completely new look in the spirit of the Seventies', but whose painfully strained attempt at a 'with-it' title dangled over its decidedly 'old look' contents like a flower-necklace perched on a middle-aged paunch. Thames TV put the series out at 6:45pm on Mondays, which was hardly a promising slot for what was supposed to be a major new show from one of its biggest and best-established acts.

Featuring 'a weekly discotheque spot' and some light-hearted observations 'on the latest happenings in the pop scene', but still relying on such familiar middle-of-the-road guests as Lionel Blair, Acker Bilk, Clodagh Rodgers and Kathy Kirby, it was a horribly half-hearted affair. Critics not only noted the double act's apparent discomfort, but also the sloppiness of the production, which saw stagehands caught on camera and guests left to wander off in the background.

The show still managed to hover in the lower part of the top twenty most-watched shows of the week, peaking at about nine million viewers, but it was a programme watched more out of custom than keenness. 'Take away the padding and the gimmicks,' one reviewer said, 'and there's not much of substance left to see.'

Rattled by the reaction, and desperate to be seen as something more than ITV's light entertainment dogsbodies, they tried to step outside of their comfort zone the following year by making their first (and, as it would turn out, only) sitcom series, called Mike And Bernie (1971-2). Written by the experienced team of Vince Powell and Harry Driver, and featuring the pair as versions of themselves, two hard-up music hall comedians, the series suffered, just like their more conventional shows had done, from a general lack of care and conviction.

Although one sympathetic observer declared that 'the brothers Winters are to be applauded for making a determined effort to escape from standing in the wings and applauding yet another "fabulous guest star"', most reviewers hated the sitcom, complaining about the 'unbelievably bad' scripts and its 'antique' themes, and dismissing the series as a whole as 'rubbish'. The stars themselves would later complain (with some justification) that they were given neither the time nor the help to develop the characters and find the right balance between the comic routines and the dramatic scenes ('Somehow,' Mike reflected, 'the series never jelled').

The flop would represent something of a watershed for the Winters brothers. Just when Eric and Ernie were being celebrated as the nation's favourites for such dazzling routines as the Grieg piano concerto with Andre Previn, Mike and Bernie were being dismissed as yesterday's men. They resented it, but could no longer find a constructive way to respond to it.

'I know that some of the stuff we had to put over on TV was not very good sometimes,' admitted Bernie sadly during this period. 'We didn't need to read about it in the papers. We've taken some terrible knocks from the critics.'

Aside from hosting a run-of-the-mill, pre-arranged, variety series in 1973, they would never star in any more TV shows after the failure of their sitcom. There would be the odd guest spot on other people's programmes, on the BBC as well as ITV, but, as far as being major figures in the medium, their time was now over, and the sense of rejection hurt. Their celebrity social circle began to shrink, the grind of the provincial theatre circuit grew more gruelling, and, forced as they were to spend more time together than ever, the tensions between them increased.

Their personal relationship would actually go into steep decline throughout the Seventies. In 1971, the pair were offered a huge amount of money to leave their long-standing agent, Joe Collins (the father of Joan and Jackie) and join a new outfit called MAM; Mike wanted to move (reasoning that, besides the welcome influx of money, they badly needed a fresh perspective to revive their flagging career), but Bernie (believing more in showing loyalty to an old friend) refused to budge.

Bernie won that battle, but would lose the war; their relationship would never be the same again. They stopped sharing a dressing room, stayed at different hotels, stopped rehearsing, went through whole performances without making eye contact, and there were many times when they refused to speak backstage not only to each other, but also to each other's wife and family (and then their wives started shunning each other, too). There were loud and very public rows at airports (which their friends in the press covered-up), and at least one occasion - in a Birmingham night club - when the brothers stood toe-to-toe and exchanged blows in front of the management.

Their last few years together, as the venues became more and more modest and the audiences smaller and smaller, would have demoralised any major act. For these two embittered brothers, it was a period in which they felt imprisoned by their mutual sense of misery.

Thanks in part to the ongoing cost of their lavish lifestyles (both were far more extravagant than Morecambe & Wise, owning large houses, employing servants, driving Rolls-Royces and Mercedes, loving long and exotic holidays, and they even had a controlling interest in a Bavarian hotel), they had little choice but to keep toiling away on what they now termed the 'dreadful treadmill', but they were dogged by disappointments.

A plan to make a feature film (The King Of Spooks) for the new home video market fell through; a couple of residencies on P&O cruises proved even more enervating than they had expected; while their regular pantos and summer seasons remained popular, the odd one-off show had to be cancelled due to poor ticket sales; an improbable album of crooning classics called For Mums And Dads Of All Ages bombed direct to the bargain bins; and a cabaret tour of Australia saw the rows between them grow so intense - and so public - that their promoter had to find ways to keep them apart whenever possible.

Mike and Bernie Winters broke up for the final time one September night (Saturday the 16th) in 1978 after completing a short summer season at Shanklin's Sandown Pavilion Theatre on the Isle of Wight. Bernie came back out and made the announcement, with tears in his eyes, just before the final curtain came down. He presented Mike with a cut-glass bowl bearing the inscription: 'To The Best Straight Man In The World'. A dry-eyed Mike, however, as everyone in the audience could not help but notice, gave him nothing back, and, after the two of them had taken their final bows, Mike went off for dinner with his family and friends, but Bernie and his wife were not invited.

There are at least a trio of theories as to what the catalyst had been that made this double act break up for good. One concerns their bookmaker father, Mougie, whose devotion to their career had always helped keep them together. When he died in 1977, by far the strongest familial bond had been broken, and, they would later say, there suddenly no longer seemed a good enough reason for them to persevere with the professional partnership.

Another account focuses on Bernie's affair with Dinah May, an actress, model and beauty queen who would eventually be crowned Miss Great Britain in 1976 (and, ironically, move on to become the personal assistant of Bernie's old bête noire, Michael Winner). They would be together for four years, starting when she was eighteen and Bernie forty. It ended when Bernie was named in a divorce suit by Dinah's husband. Mike, who was conducting one of his own extra-marital affairs at the same time, reacted to the news by mocking Bernie for 'getting caught', and, following a fierce physical fight, Bernie never forgave him for the lack of sympathy and support.

A third version suggests that the two performers were simply exhausted, out of ideas, demoralised by the decline in their status within the business, and ready to move on in different directions. Mike would indeed later claim that they had 'reached stagnation in our performances'.

The truth is probably some combination of all three. For multiple reasons, the partnership had petered out.

Mike went off to Miami in America, where he wanted to pursue a new career as a writer and impresario. Bernie stayed in England, where he would form a new partnership, of sorts, alongside a newly-hired dog, posing as a long-time family pet, called Schnorbitz. Just before Mike flew off to Florida, Bernie (always by far the most sentimental of the two) phoned his brother to wish him luck; Mike's curt response was to tell him that his new TV show was 'dreadful'.

Bernie would go on to star in several of his own series (as well as winning considerable critical acclaim for his portrayal of Bud Flanagan, alongside Leslie Crowther as Chesney Allen, in a stage play about the older double act, Underneath The Arches), and, if anything, enjoyed an even warmer relationship with the viewing public than he had done during the days working alongside his brother (even though his comedy suffered significantly without the assistance of a regular and reliable straight man).

Mike, meanwhile, would try to sell a variety of TV format ideas (including one, ironically, that he saw as a solo vehicle for Ernie Wise), opened a theatre club (The Mike Winters Room at the Versailles Hotel in Miami), got involved with the boxing business (sometimes in partnership with Angelo Dundee, the trainer of Muhammad Ali), published five books (including a Chandleresque novel about a psychopathic murderer in the world of showbiz called Razor Sharp) and also played a prominent role in a number of local charities.

Neither brother, whenever they were asked, was keen to talk about the other, but, at least initially, both of them preferred to encourage the myth that the split had been perfectly amicable. All of that changed, however, late in 1980, when Mike gave an interview to the Sunday Mirror, admitting that the break had indeed been a bitter one. Blaming the ongoing feud on Bernie (who had recently told friends that 'absence doesn't make the heart any fonder'), Mike remarked: 'Our parents would turn in their graves if they knew he was behaving this way'.

Bernie retaliated the following year, when (at the prompting of his formidable wife Siggi, who, as a condition of her forgiving him for his past transgressions, told him 'it's time to come clean in public') he reminisced about their rows, as well as his own affairs, to the Daily Mirror. He, predictably enough, blamed it all on Mike.

They were reconciled, at least to some extent, in 1985, following seven years of icy silence, when Mike returned briefly to England to undergo a minor operation. 'I didn't know he was in London until I saw him in the street,' said Bernie, somewhat disingenuously. 'Now we're mates again.' 'It was a feud that finally got on top of us,' Mike added. 'I'm so happy it's over.'

Bernie died on 4th May 1991, after a year-long battle with illness, aged just fifty-eight. Mike (who attended his brother's funeral) passed away on 24th August 2013, aged eighty-six. Although it always niggled them that some critics had called them 'the poor man's Morecambe & Wise', it was surely a far greater cause of regret that circumstances prevented them from becoming the rich man's Mike and Bernie.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreMike Winters - The Sunny Side Of Winters - A Variety Of Memories

Autobiography from Mike Winters, best known as part of the double act Mike & Bernie Winters.

In this fascinating, unpretentious account, Mike shares his precious memories and stories. They cover many years and involve an eclectic mix of stars and characters.

First published: Thursday 24th June 2010

- Publisher: JR Books

- Catalogue: 9781907532023

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.