Michael Bentine - A Goon who should not be forgotten

There are some significant figures in British comedy who seem to have been, more by carelessness than calculation, airbrushed out of its history. Michael Bentine is one of those unfortunate people.

He was a co-founder of The Goons, and yet, when The Goons get mentioned these days, he is usually overlooked. He was an award-winning pioneer of technically inventive television comedy, and yet, once again, he is often ignored when that era gets examined. He was also one of the first to make original comedy shows for children, but again his achievements in this area appear to have been largely forgotten. He used to be cited as one of the key influences on the Pythons, but his name seems to have slipped off that particular list as well.

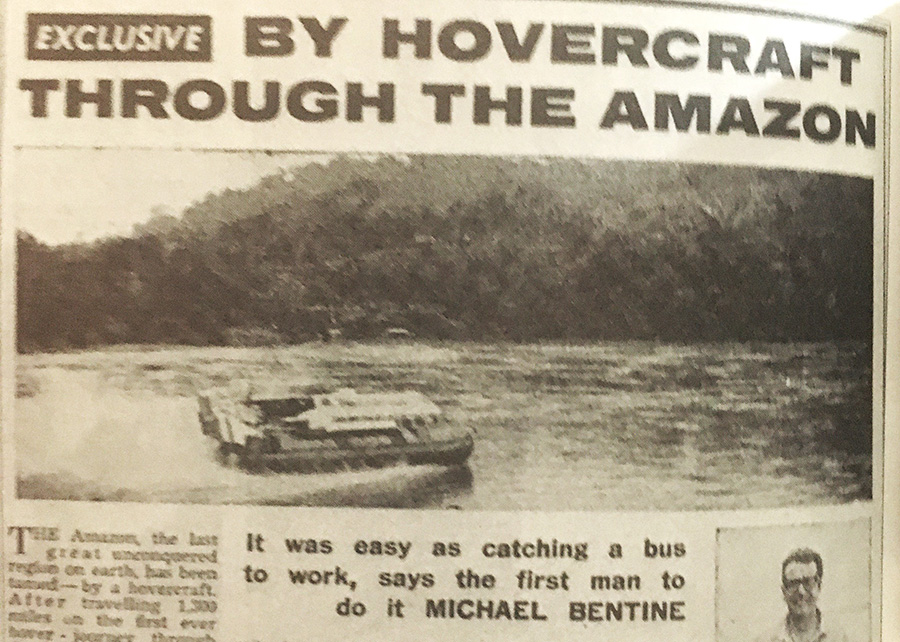

Even beyond his contribution to British comedy, it is rather odd that one so seldom hears these days about someone who lived such an extraordinary life. The grandson of an eminent South American politician, and the son of an aeronautical engineer and valued inventor, he was educated at Eton; served as an RAF Intelligence officer during World War Two; took part in the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp; was a charity worker, art collector and firearms instructor; acted as an advisor to Special Branch; helped set up the counter-terrorism section in the SAS 22 regiment; and took part in the first hovercraft expedition up the River Amazon.

2022 is actually the centenary of Michael Bentine's birth, and it therefore seems fitting for us now to remember this under-valued entertainer and intriguing individual, and reflect on the various ways in which his influence, though often unacknowledged, continues to be felt on the forms that he graced.

He was born at Tusmore Lodge in Watford, Hertfordshire, to a Peruvian father, Michael Miguel Adan Bentin, and a British mother, Florence Dawkins, and grew up in Folkestone, Kent. Bentin Snr's family pedigree was quite a prestigious one, but it was not quite the one that his son would later claim.

According to Michael's own account (perhaps the product of various family recollections being mixed up over time in his mind), Antonio Bentín, his paternal grandfather, was a vice-president (and then president-elect) of Peru, and this assertion, strangely enough, was never checked and, even though it is hardly a challenge to clarify, continues to be cited uncritically as a straightforward biographical fact. The truth is rather different, though arguably just as impressive.

Antonio Bentín La Fuente y Palomera, the son of an English immigrant and a Peruvian aristocrat, was actually a silver miner-turned-politician who became mayor of Lima, co-founded and led the Democratic Party of Peru, became President of the Council of Ministers, and Minister of Government in the constitutional government of the hugely influential leader Nicolás de Piérola. He appears to have lived longer than the fifty-five years that Michael said - according to most records it was actually seventy years, with his death in 1897 - and continues to be seen as a key figure in the political history of Peru during that era.

His son, Adan - he would later change it to Adam - was sent over to England as a teenager to study engineering with a view to using the expertise back in Peru for the family's various industrial interests. Adan, however, was a restless, inquisitive individual who, although earning his qualifications in his primary profession, became distracted by other interests, which ranged from making numerous inventions to living on a farm and raising horses for show jumping.

Although he married Florence in July 1915 (and she would give birth to their first child - Anthony - the following year), he was still regarded as an 'alien' by the British armed forces to which he applied during the early years of the First World War, but was eventually accepted for his engineering skills, and ended up inventing a tensometer for setting the tension on aircraft rigging wires. He was invited back to Peru in 1920 by the Government to oversee the building of its new air force, but, uneasy about the growing political disruptions in the country at the time, Bentin soon decided to return to England, and his and Florence's second son, Michael, was born there in 1922.

Michael would have a challenging childhood. His self-confidence was greatly undermined by the fact that he started suffering from a stammer.

It was the result of a badly-bungled tonsillectomy that had been administered, when he was just four, by a drunken doctor on the family's kitchen table. The spectacularly incompetent physician somehow managed to tear out half the boy's nasopharynx, as well as his swollen tonsils, and the shock that followed such a savage operation caused the child first to lose his voice completely and then start speaking again with a stammer that would stay with him until the age of sixteen.

Often obliged to write things down in order to communicate, his subsequent use of humour in his day-to-day life was partly to do with his naturally oblique outlook on the world around him, but was also down to a desire to make himself popular with other children in spite of his struggles with speech. It was, he would say, 'an important part of my survival pattern'.

Things only started to improve when his parents - whose fortunes would fluctuate erratically over the years - found the funding to send him to Eton (where his contemporaries would include Humphrey Lyttelton, Patrick Macnee and Ludovic Kennedy). Protected there by his tutors from too much harmful teasing, he began to lose some of his shyness as he started excelling at cricket as well as embracing the privileged academic education he was receiving.

It was while he was at Eton that he finally started to lose his stutter. A Wigmore Street speech therapist named Harry Burgess volunteered to help him through the psychological as well as physical challenges to speaking more clearly with confidence, and, eventually, it worked.

He gradually became so much more relaxed in the way that he spoke that he started taking an interest in amateur dramatics, becoming an increasingly effective and amusing performer as he moved from play to play. Popular with his fellow pupils and fussed-over by his tutors, he was expected to go on to impress at university. Then ill-fortune, quite literally, intervened.

His parents, who were also supporting their other son, Tony, in his studies at the Royal College of Art, concluded with great reluctance that they simply could not also keep up with the fees for Michael at Eton. He was thought of so highly there that he was offered free board in exchange only for tuition charges, but his father decided that, at seventeen, it would be best for Michael to leave.

The Second World War broke out before the family had time to plan his next steps, and Michael, after overcoming the same bureaucratic obstacles that his father had faced, was eventually conscripted into the RAF and readied for flight training. His poor luck continued, however, before the work could even start.

He was one of the last three in the queue for inoculations for typhoid, prior to a trip to Canada, when the vaccine ran out. The medical staff refilled the bottle to inoculate him and the two others, but by mistake they loaded a pure culture of typhoid. Of the other two men injected, one died immediately and the other was paralysed for life, while Bentine, after collapsing from convulsions, was left in a coma for six weeks.

One of the lasting effects of the infection was that it weakened his sight, thus rendering him no longer qualified to fly. After refusing an honourable discharge, he was sent instead to RAF Intelligence and then seconded to the Colditz escapee Airey Neave at MI9, a unit dedicated to supporting resistance movements in various parts of the world, training people in the diverse and devious ways of liberating themselves from confinement. He was also involved in the D-Day invasion, as part of one of the first Allied troops to liberate the concentration camps - the horrifying sight of which, he would say, struck him as 'the ultimate blasphemy'.

Once demobbed in 1946, and desperate to get away from darker things, he added an 'e' to his surname to give it a more 'British' sort of sound and decided to try his hand at comedy. Reuniting with an old friend called Tony Sherwood - a jazz pianist with whom he had once played drums for a handful of gigs while they were waiting for their call-up papers early on in the war - they worked out enough off-beat routines to start doing the rounds as a double act.

Calling themselves 'Sherwood and Forrest', they tried and failed at a number of auditions (mainly on the grounds, it seems, that they were deemed 'too sophisticated' for the popular tastes of the time) until they arrived at the Windmill - the small West End theatre that had become notorious as the only 'legitimate' venue in London offering nude shows as well as variety. Much to their surprise, they passed the audition there, along with a young Welsh comedian and singer called Harry Secombe, and were immediately slipped into a gruelling schedule consisting of six performances a day for six days a week for six solid weeks.

The all-too brief Sherwood and Forrest partnership reached its climax at the end of that year when the duo was booked to appear in a live BBC television broadcast. Bentine would later misremember the date as being Christmas Day, but it was actually 12th December, when they were featured alongside other several other variety performers as the main entertainment of what was still a very limited schedule. They would be unable to build on this breakthrough., however, as Sherwood had just won a scholarship to study at the Guildhall of Music, and Bentine was left to pursue a solo career.

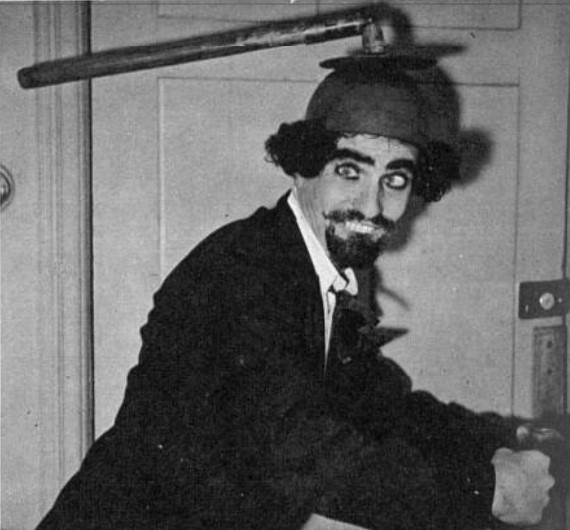

He worked on his image - growing his dark curly hair long and thick, adding a similarly unruly beard, donning oversized black-rimmed spectacles, and affecting the air of an eccentric academic - and devised a new bit of comic business that he called his 'chairback routine'. He would come on to the stage holding only the back of a supposedly antique chair, and give a passionately patriotic speech while using the fragment of chair to illustrate everything from brave soldiers in battle to earnest labourers at work in the fields, and from pneumatic drills to ceremonial trumpets, before eventually passing out from exhaustion (Peter Sellers would later tell him that this skit, with its sudden jerky movements, was the inspiration for the prosthetic arm routine in Dr Strangelove).

He also came up with an incomprehensible language, a strange blend of cod-Russian and fake French, which he used to 'explain' complicated-looking devices and procedures. He would complement these eccentric disquisitions by brandishing such improbable props as rubber chickens, kettles, soup spoons, concertinas and walking sticks.

One of the places where he performed this strikingly unconventional act was the Nuffield Centre in London's Soho, a charitable club 'for the forces of the Crown' to which many ex-servicemen - including Tony Hancock, Tommy Cooper and Benny Hill - were drawn in the hope of being noticed by someone of influence. Bentine achieved just that, catching the eye of an agent called Monty Lyon, who was so impressed that he signed him up there and then and soon got him a regular spot at the Hippodrome Theatre in a show called Starlight Roof.

Hosted by the established comic personality Vic Oliver, and also featuring the lugubrious comic Fred Emney, the dancer and singer Pat Kirkwood and a very young Julie Andrews, it represented a major step forward for Bentine's career, as he not only started earning an increasingly healthy weekly wage but was also getting occasional work in radio. This would be a significant period in his personal life, too, because it was while he was appearing in Starlight Roof that he met and married his second wife Clementina (his first marriage, during wartime, had ended in divorce), who was one of the dancers in the corps de ballet.

He went straight from the run of Starlight Roof to another production at the same theatre, this time called Folies Bergère.. Hailed by the critics as an exciting and innovative young 'crazy comic', he achieved nationwide fame when he was selected to appear in the 1949 Royal Variety Performance and promptly made one of the biggest impacts of the evening ('it was that happy imbecile Michael Bentine,' reported one paper, 'who made the two princesses applaud with even more gusto than the rest').

By the following year he was being discussed by numerous commentators as the leader of and spokesman for a new breed of British comedian. The Stage, for example, gave him one of its pages to expound on the nature and needs of 'his' young followers, which he used to stress the great importance of originality and better writing in the move to find fresh ways to amuse.

It was during this period that the seeds of The Goon Show started being sown. First, Bentine began socialising after work at Grafton's, a family-run pub in Strutton Ground, Westminster, owned by the scriptwriter Jimmy Grafton. After becoming friendly with the host, he introduced his old friend Harry Secombe to the place, who in turn started bringing another former comrade from the services, Spike Milligan. Peter Sellers was also drawn to this group, and the four of them rapidly became an unofficial comedy group, sharing funny stories and improvising new routines and bits of business over sticky tables and glasses of beer.

It was Bentine, at this stage, who, as the busiest and best-known of the quartet, used his public profile to start helping to promote their common cause. He would later claim that the first mention in print of their collective phrase 'The Goons', for example, had come in a Picture Post article dated 5th November 1948 (another assertion which, disappointingly, has been repeated many times over the years without anyone bothering to verify it, even though it only takes a matter of seconds to reveal that the magazine was not actually published on that date), but there was certainly another piece, dated 10th March 1950, which referred to Bentine as 'the chief founder and inspiration of their club', and several more pieces, ostensibly about Bentine alone, were 'massaged' by him into serving as plugs for the others as well.

They would eventually get their big chance in radio as a team, with the first series of Crazy People, as it was called initially, beginning on the BBC on 28th May 1951. According to many of those who heard them, these early episodes were an ill-disciplined mess, which was partly the point, but they also had some moments of inspired comic daring and invention that captivated some and confused others.

Milligan, initially, was credited by the BBC as the one who 'compiled' the material, but Bentine (along with Larry Stephens and Jimmy Grafton) would often have as much input as he did when it came to shaping many of these shows. He would also encourage and assist the others, at various times and in numerous ways, as they cultivated their own cluster of characters.

Bentine himself would play a mad professor called Osric Pureheart, the man who invented the solid lead violin for deaf musicians, helped dig the Suez Canal, construct Croydon airport and devise a machine to trip through time, and would also contribute the calmer tones of the sober announcer and rhyming slang cipher Hugh Jampton. He realised, however, that Peter Sellers, especially, was far more facile and versatile as a vocal performer, as well as more assured in the way he could immerse himself in another personality, and so he was content to act as an unofficial editor as his colleague experimented with sounds and styles ('He wasn't an originator,' he said of his friend, 'but if you gave him a voice, he could develop it').

Sellers would also credit Bentine, and his endearing habit of being overly-polite when dealing with unwelcome visitors ('He was always calling everyone a genius'), for inspiring, albeit indirectly, Bluebottle's notoriously high-pitched and nasally voice. It happened when a strange spindly man dressed as a Boy Scout Master - one Ruxton Hayward, as it happened - having already bothered Bentine backstage at the Chiswick Empire, knocked one evening on the door of his friend's London apartment.

Sellers would remember:

He was a tall fella. He'd got this little briefcase, and he'd got a scout hat, but he'd got a big red beard with all this, and red knees and socks and insignia, you know? And he said - and I'm not kidding, this is how he spoke: [Bluebottle voice] 'Could I come in for a moment, please?' And I thought, 'What is THIS???' But I said, 'Yes, certainly, what can I do for you?' He said, 'I have just seen...Michael Bentine...a-at Chiswick...and he said that I am a genius.' And then he asked me if I'd do a concert at the Sulgrave Road Boy's Club or something. So I said, 'No, sorry, I don't think so' - it was after a show on Saturday night, I'd have to pack up and run, it was the last thing I really wanted to do at that stage, especially if he was an example of what I was going to find down there! But he took this as a hint. He said, 'There, um, is a fee involved...' So I said, 'No, it's not a question of money, I can assure you, really. I would come but I just can't at the moment.' So he stood there for a second and then he said, 'Oh well...Just a thought.'

When it came to the working relationship between Bentine and Spike Milligan, there was always something awkward about it. It came together well enough to bring The Goons into existence, but then fell apart quickly enough to undermine much further progression.

It was natural, in a number of significant ways, for Bentine and Milligan to bond as people. Both of them, for example, had an ambivalent attitude to Britain.

Milligan had been born in British India to an Irish father and an English mother (and in 1962, after the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, the country for which he had fought would end up declaring him stateless). Bentine, as a patriotic Englishman who was part-Peruvian, had (just like his father before him) been angered when subjected to racism and xenophobia in the past, and been turned down several times before being accepted by the RAF on the grounds that he was deemed a 'non-European'. Both men, therefore, never lost the feeling that, in a sense, they were outsiders who were not quite trusted in their own country.

The two of them also had a deeply-entrenched suspicion of authority, despising the bullies and the boors who used their high place in the hierarchy to humble all of those below. Both men had been treated badly at times during the war by their so-called superiors, and, in spite of acknowledging the need for discipline and order while the conflict was current, still noticed and noted the excesses and inanities of those too attached to the power that came with their position. As Milligan later said, he was driven in peacetime 'to knock people my father and I had to call "Sir"'.

They also, although both were fortunate enough to have lived in privileged circumstances early on in their lives, had an instinctive sympathy for the underdog, the under-privileged and the exploited. Milligan would rage at the post-war disparities between the rich and the poor, unhesitatingly pledging his allegiance to any radical cause that came his way. Bentine, as a teenager, had reacted with revulsion to the 'gloom-fest' that had followed the death of George V, with the 'enormously expensive pomp and circumstance' of the royal funeral striking him as being in appalling taste at a time when many 'miners, ship-builders, steel workers, craftsmen and labourers, as well as white-collar workers, had no prospect of employment, and many of their families were in a state of semi-starvation on the shameful pittance of the dole'.

Both men were also haunted by the horrors of war. Having seen what so-called 'civilised' human beings had done to each other in the name of some or other ideology, they were forever fighting their own cynicism to preserve their fragile sense of hope.

They would therefore write and speak, for a time, with one voice, emotionally, as they worked to create comedy that, as Bentine later put it, was a dedicated attempt 'to show that sacred cows all have hooves of clay'.

There were also, however, tensions between the pair of them that, although mild to begin with, soon grew increasingly noticeable and problematic. On a personal level, Milligan was somewhat intimidated by, and envious of, Bentine's superior education and articulacy; Bentine, in turn, was exasperated at times by Milligan's struggles to explain what was happening inside his head. On a professional level, Milligan started irritating Bentine with his scattershot and impatient approach to comedy; Bentine began niggling Milligan with his slower and more methodical way of constructing material ('Michael provided most of [the ideas],' he would later admit. '[But] he would have one joke which took four minutes to build up. It's his style, he needs room to work').

Their producer, Dennis Main Wilson, would later sum up their essential difference as being that between the organic and the inorganic: 'Michael was the technical creator of documentary items, in terms of humour, but they had no heart and no soul in them. Whereas Spike had great heart, great soul, and great imagination, but he wasn't that good at technique...yet.'

It was an unfair assertion by Main Wilson, which had far more to do with his close emotional identification with Milligan than it did with any impartial analysis of Bentine. The latter's work had plenty of heart and soul but, while Milligan (and, by his own later admission, Main Wilson, too) often lacked the discipline in those early days to organise his ideas into a workable radio programme, Bentine was frequently obliged to step in and bring some order to the chaos - and (in a similar way to what happened to Paul McCartney vis-à-vis John Lennon in The Beatles) while that might have allowed some onlookers with an axe to grind to depict him, unjustly, as the less romantically creative spirit of the pair, it probably prevented several shows from ending up being untransmittable.

Arguably a better way to put it, as far as the two men's differences go, is to say that Milligan was made for sound and Bentine for vision. As Bentine himself would later reflect: 'I'm always sparked off by a visual idea which I have to find words for. Spike is usually sparked off by an idea which is essentially non-visual and which he then makes visual.'

Torn in this way, it was therefore no great surprise, at least to insiders, when Bentine decided to leave the show in 1952 to go solo after completing the second series. It was not, contrary to his later diplomatic claims, an amicable split.

Milligan later asserted: 'He tried to get rid of me from The Goon Show. I didn't leave - so he did. That was it.' Bentine would contest this account, insisting the real reason was that he came to the conclusion that there was only room in the group for one 'self-contained writer-performer unit'.

Whatever the truth of the matter, it seems that both parties, once the dust had settled, agreed that the break was for the best. Milligan could now feel fully in control of The Goon Show, even though a new producer (Peter Eton) was brought in to provide the rigour that had previously been left to Bentine. The latter, in turn, was at last free to indulge his urge, as he put it, 'to apply my logical nonsense' instead of Milligan's 'nonsensical logic'.

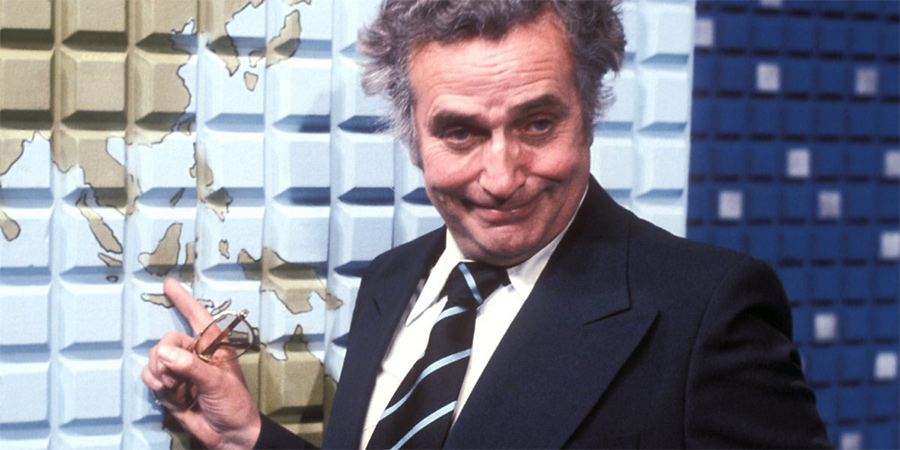

What Bentine would subsequently achieve on television as a solo writer and performer was worthy of respect and admiration in its own right. One of his most admirable contributions was to demonstrate that one could make creative and entertaining programmes for younger viewers without ever under-estimating their intelligence.

First in 1954 on BBCTV with The Bumblies (which starred three tiny alien ambassadors from the Planet Bumble, and aimed at encouraging children to think of anyone 'alien' as a friend rather than a foe) and later, from 1973 to 1980 on ITV, with Michael Bentine's Potty Time (which featured bearded puppets - the Potties - comically re-enacting famous events and incidents from history), he produced shows that were among the most successful and influential of their time and type.

The second project was poignant as well as playful, because it was partly inspired by Bentine's determination to fight back against the despondency and bitterness that he felt after the tragic loss of his son Gus, at twenty-one, in a light aircraft crash in 1971. Moved by the beneficial effect his earlier work had had on children, he returned more eager than ever to reaffirm for them that humour was a force for good: 'I don't laugh at people,' he stressed. 'I laugh with them'.

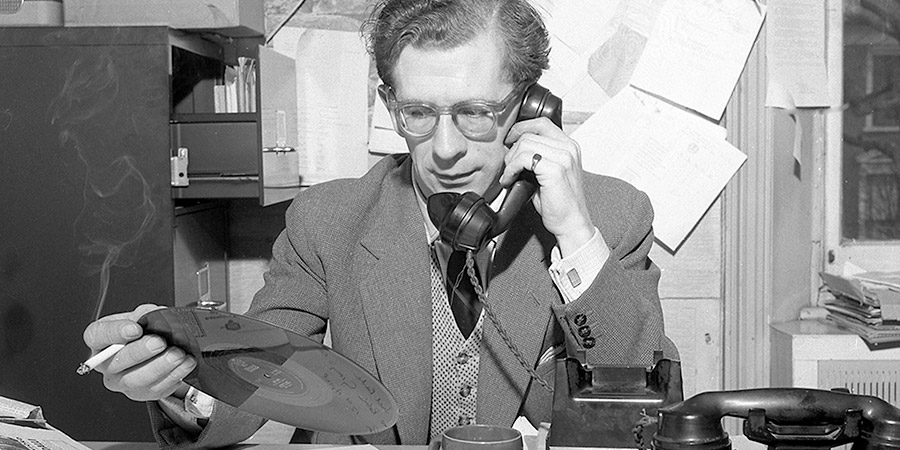

His so-called 'adult' work had a similar message. It's A Square World (1960-64), in particular, was a joyously imaginative affair (co-written by Bentine and John Law) that, with its technical tricks and gently satirical outlook, would be one of the significant creative influences on the likes of The Frost Report, Do Not Adjust Your Set, Monty Python and The Goodies. Exploiting whatever clever visual effects were currently available, while inventing one or two more of its own, it combined a sharp wit with an excellent cast (it included Clive Dunn, Dick Emery, Ronnie Barker, Frank Thornton and Bob Todd) to become one of the freshest and most enterprising comedy shows that British television had so far seen.

Among its many features was a flea circus that used special effects to show them leaving footprints as they walked across the sand, and depressing each rung of a ladder as they rose before diving off into a teacup. Bentine collaborated with Jack Kine and his team, from the BBC's Visual Aids Department, to make such ideas work on the screen.

There were also mock news stories, sketches, parodies of 'serious' shows, spoofs of movies and documentaries, as well as animated sequences. The show also relished every opportunity to stage fake invasions of, and attacks on, the very building that housed it: Television Centre. Characters were seen trying to dig their way out of it or blast their way into it; it was shot at by pirates and buzzed at by planes; it was torpedoed by a German U-boat and showered with arrows by Native Americans; and on one occasion it was propelled by rockets up into space.

Eventually, after one stunt, involving just a tiny amount of explosives, left a few of the building's bricks looking slightly sooty, Bentine and his team received a stern memo from on high which would continue to make him laugh for the rest of his life. It simply read: 'Under no circumstances is the BBC Television Centre to be used for the purposes of entertainment'.

Running for seven series in four years, the show received widespread praise from reviewers and public alike, and won a BAFTA award for Light Entertainment in 1962 and the International Critics' Award at the Montreux Festival of Television in 1963. The 'brusque and reluctant' reaction of the BBC to the latter achievement - a distracted Kenneth Adam, the BBC's Director of Television, mumbled about 'winning some kind of award' and invited Bentine 'upstairs' at TV Centre for a glass of warm champagne - would rankle with the programme-maker, and he responded in a subsequent show by having all of the building's top brass destroyed by a giant man-eating orchid.

There would be many other appearances on stage, radio and television, as well as a notable foray into films with The Sandwich Man (1966), but, from the late 1960s onwards, Bentine, much like Milligan, would never really feel properly appreciated by any British broadcaster, and struggled in later years to find a suitable outlet for his diverse talents. He was fortunate, however, to have, unlike many of his contemporaries in the industry, a hinterland to explore.

Among his many other interests were reading; writing; art; travelling; building and sailing ships; gliding; teaching fencing, archery and shooting (but never, with the latter, at living things); astronomy; advising security forces on various operations; campaigning for stricter privacy laws; designing artificial cows; and exploring spiritualism and psychic phenomena. One of his most notable adventures took place during the spring of 1968, when he travelled to South America on an 'I'm Backing Britain' initiative to sell British-made hovercrafts. He and the rest of the crew became the first to take such a vessel through 1,300 miles of the upper Amazon complex, breaking no fewer than four world hovercraft records in the process, before arriving for trade talks in Peru (where his influential relations included the heads of the airline, tourist board and two of the country's biggest breweries).

Bentine would be honoured by both of his countries. In 1970, he was made a Commander of the Order of Merit for Distinguished Services by the Government of Peru after raising funds for the many victims of its recent earthquake. Britain appointed him a CBE in 1995 'for services to entertainment'.

His health was already failing when he received the latter honour. Diagnosed with cancer, he refused chemotherapy, having already seen what his two daughters went through when they had the same disease (Elaine died, at forty-one, in 1984, and Marylla, aged thirty-five, in 1987). 'I want to see,' he said, 'how long humour can help me.'

One of the many people who called him during his final few months was Spike Milligan, and the pair of them were finally reconciled, though with considerably more magnanimity on Bentine's side than Milligan's. Always a great favourite with the Royal Family, Bentine was also visited privately by Prince Charles, as he then was, in London's Royal Marston Hospital on what would turn out to be the comedian's last day alive. 'When Charles walked in,' said his son, Richard, 'my father woke up and the two of them had the most ridiculous and funny conversation. It gave me back my father for an hour.'

He died on 26th November 1996, aged seventy-four, surrounded by his wife and their two remaining children. Among those who paid tribute was his old Goon Show producer Dennis Main Wilson, who on this occasion found the right words when he said: 'Michael was very, very eloquent. I loved him. He was over-generous to a fault to all his friends. He was a smashing guy.'

Sir George Martin, who oversaw the comedy recordings that Bentine made in the Sixties, praised the range of his work and called him 'a marvellous man. I never heard him speak ill of anybody'. Michael Palin acknowledged the debt that later comic writers and performers owed to Bentine's off-the-wall humour: 'He had a bizarre, surreal sense of humour, very un-mainstream.' One of his oldest friends of all, Harry Secombe, said: 'He could act, he wrote very well, he was a very funny comedian. He was a genius.'

Michael Bentine once said that the success or failure of his various shows didn't really matter to him. 'What matters,' he added, 'is that you've put your heart and soul into it and done your best.'

He always did his best, and at his peak his best was better than many of those who are now better-remembered. It is thus about time, in this, his centenary year, that we started putting that right.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreMichael Bentine's Potty Time - The Complete First Series

Potty Time was a popular and beloved UK television puppet show that began in the 1970s and was the wacky creation of the multi-talented writer/director Michael Bentine. Universally vertically challenged, the Potty hand puppets were characterised by their prominent noses and costumes that obscured their other physical characteristics. Bentine's beloved show, which was geared for children but boasted an adult audience as well, offered a challenge to accepted notions of many aspects of life and was regarded as harmlessly rebellious. The highlight of Potty Time usually involved a mini-explosion of some kind, as Bentine knew this would delight the kids at home.

First released: Monday 26th January 2004

- Distributor: Network

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 286

- Catalogue: 7952194

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Michael Bentine's Potty Time - The Complete Second Series

The pages of the great Potty Encyclopaedia are opened once more with 13 classic episodes of this marvellously madcap puppet series - a favourite of children and adults alike.

Created, written and presented by the multi-talented Michael Bentine (The Goons), Potty Time ran for a total of seven years between 1973 and 1980, and was voted into 71st place in Channel 4's 100 Greatest Kids' TV Shows poll of 2001.

Watch re-enactments of some of the world s greatest historical events with a unique Potty slant, and learn little-known facts from the venerable Professor Potsworthy - the source of all Potty knowledge. Who really won the Battle of Waterloo? Why was Troy rebuilt thirteen times? Who made the first attempts at flight? And who was Viva Zapotti? Enter the parallel Potty universe, and all will be revealed!

First released: Monday 7th February 2011

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 2

- Minutes: 325

- Catalogue: 7953375

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Michael Bentine's Potty Time - The Complete Third Series

The pages of the great Potty Encyclopaedia are opened once again with thirteen classic episodes of this marvellously madcap puppet series, a favourite of children and adults alike.

Created, written and presented by the multi-talented ex-Goon Michael Bentine, Potty Time ran for seven years and was voted into 71st place in Channel 4's 100 Greatest Kids TV Shows poll.

Watch re-enactments of some of the world's greatest historical events with a unique Potty slant, and learn little-known facts from the venerable Professor Potsworthy the source of all Potty knowledge. Discover how the Potties of Ancient Britain defended themselves against Viking raiders... revisit the Age of Chivalry, when Knights were bold and battled for a good Potty cause... hear stirring tales from the Potty Pilgrim Fathers, who sailed to a new life on the April-Flower... find out why the Great Wall of China was really built... and a great deal more besides!

First released: Sunday 21st August 2011

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 2

- Catalogue: 7953571

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Michael Bentine's Potty Time - The Complete Fourth Series

Created, written and presented by the multi-talented Michael Bentine (The Goons), this marvellously madcap puppet series re-enacted some of the world's greatest historical events and shed new light on mysteries ancient and modern all with a unique Potty slant. Running for a total of seven years between 1973 and 1980 and becoming a favourite of children and adults alike, Michael Bentine's Potty Time was voted into 71st place in Channel 4's 100 Greatest Kids TV Shows poll of 2001.

In this fourth series, we find out why Francis Drake's global circumnavigation took quite as long as it did, discover how America really won its independence, marvel at the grandeur and excitement of the Potty Roman Games, learn of the ingenious escapes from Warmditz by the Potty prisoners of war... and much, much more!

First released: Monday 7th November 2011

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 175

- Catalogue: 7953596

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

Spike & Co.

This is the story of how four people, grouped together inside a set of offices five floors above a greengrocer's shop on Shepherd's Bush Green in West London, launched a golden age of British comedy.

On any weekday morning, if you dared to clamber over the crates of fruit and veg outside on the pavement, and climb the five flights of stairs to Associated London Scripts, you would find Spike Milligan, Eric Sykes, Ray Galton & Alan Simpson, shaping the latest shows, swapping the odd story and searching for a funnier line.

Together, this eclectic bunch, and their bizarre office block, were responsible for a golden age in British comedy, which included The Goons, Hancock's Half Hour, Sykes, Steptoe And Son, Comedy Playhouse, The Frankie Howerd Show, Beyond Our Ken, Round The Horne, The Arthur Haynes Show, The Army Game, Bootsie & Snudge, That Was The Week That Was, and Till Death Us Do Part.

Spike & Co. is their incredible story.

First released: Thursday 19th October 2006

- Published: Wednesday 25th October 2006

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Minutes: 137

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 448

- Catalogue: 9780340898086

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Published: Thursday 9th August 2007

- Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

- Pages: 448

- Catalogue: 9780340898109

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.

- Released: Thursday 5th October 2006

- Distributor: Hodder & Stoughton

- Discs: 2

- Catalogue: 9781844563111

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.