The increasingly big balls of Martin Lewis

Following on from the profiles of Jack Hylton, Val Parnell, Lew Grade and Bernard Delfont, here is the fifth article in this occasional series within Comedy Chronicles in which Graham McCann looks at the main impresarios involved in comedy over the past century.

There has never been anyone quite like Martin Lewis in British comedy or, indeed, in British popular culture more generally. Looking for his influence is a bit like looking for snowflakes in the middle of a blizzard - it's all over the place, and it's very hard to focus.

A veritable Swiss Army knife of a show business operator, he has been a producer, but also a director, scriptwriter, performer, TV and radio host, record company executive, music video maker, journalist, consultant, artist manager, publicist, marketing strategist, entrepreneur, archivist, film festival curator, fundraiser, social activist and international cultural commentator. Describing himself as 'the world's least-reserved Englishman', he's been visible and vocal in show business for more than fifty years, from Cricklewood to Hollywood, and he's still going strong today.

As far as comedy is concerned, he keeps popping up, as you trawl through the archives, like a self-assertive and sugar-rushed version of Zelig. He discovered Alexei Sayle; helped get Billy Connolly his big break on Parkinson; worked with, amongst others, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett, all of the Monty Python, Goodies and Comic Strip troupes, Rowan Atkinson, Peter Ustinov, Victoria Wood, Barry Humphries, John Bird and John Fortune, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, Bill Maher, Garry Shandling and Robin Williams; organised tributes to the likes of Peter Sellers, Richard Pryor, The Rutles and Neil Innes; and not only came up with the name The Secret Policeman's Ball but also helped Amnesty International turn its comedy (and music) concerts into internationally successful and hugely influential social, cultural and commercial events.

As extraordinary as his career has been, there was, looking back, something compellingly inevitable about it. Born on 24 July 1952 in Ashtead, Surrey, and raised in Hampstead, he grew up a Beatles fanatic, a comedy obsessive and a show business devotee. Once he was expelled from his public school (University College in Frognal) at the age of fourteen (for inserting, prematurely, the death notice of his unloved Latin tutor in the pages of The Times), there was no doubt as to his destination.

After working as a freelance journalist for a number of London-based music publications, he gravitated to a record company, Warner Bros Records. It was there that he was taken under the wing of the famously urbane, playful and irreverent Derek Taylor, The Beatles' former press officer ('I was supposed to be writing press releases and artist bios, but I spent most of my time at his feet, listening to old Beatles stories'), and emerged fully-primed to pursue a similarly individualistic path to multiple positions of influence.

Unlike those more traditional comedy producers who always worked within a particular medium, such as television or theatre, Lewis was well ahead of his time as a sharp-eyed and tireless outlier, always able and ready to anticipate trends and go where the latest action is, be it on TV, the stage, radio, records, movies or online, and help bring a new comic project to fruition. There was something Barnumesque about his ambition, but also something very British about his disposition.

First would come the spark of excitement at the arrival of a new idea. Then there was the ignition of energy required to sell it (many people, obliged to endure a Lewis hard-sell - the relentlessly excitable phone calls could last for three, or even more, hours - would be left exhausted by the experience). Then there was the extraordinary 'rinse-and-repeat' absence of embarrassment that allowed him to move on from those long-promised projects that never actually happened straight on to the new ones that he promised really would happen in the near future. He would always, nonetheless, retain just enough of a sense of self-deprecation, and idealism, to make at least some of the sceptical pick up the phone, sigh, sit back, and listen all over again - and sometimes all the talk really would lead to action.

Rather than attempt the impossible task of encompassing the whole of this long and wide-ranging career, therefore, we will focus here on the vital role that he played, as producer and promoter, of Amnesty International's remarkably successful and influential move into organising comedy events.

The reason why Amnesty first became involved in comedy during the mid-1970s was, quite frankly, because it was desperate to raise more money. 'We were getting steadily poorer', its then-Assistant Director, Peter Luff, would later explain. 'Most of our fund-raising came from authors such as John Fowles, Samuel Beckett or Margaret Drabble giving us their manuscripts to auction'. Inspiration came early in 1976 in the form of a one-off celebrity donation, with a cheque signed 'J. Cleese'.

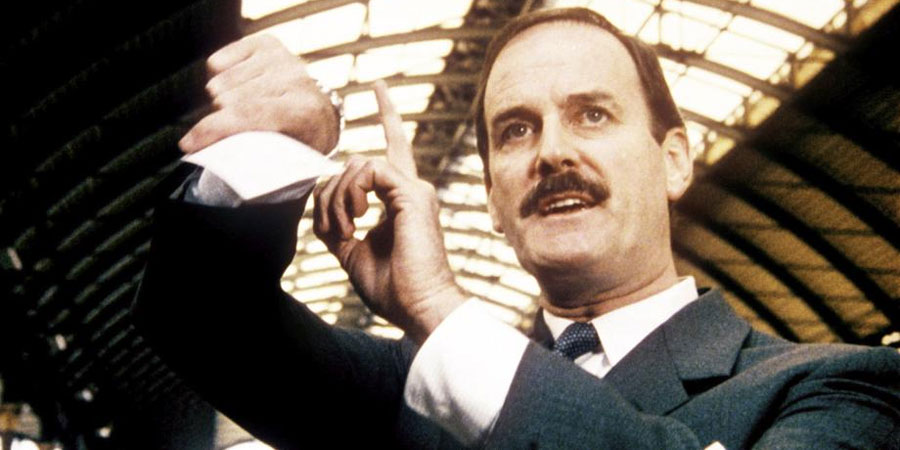

John Cleese had recently decided to join Amnesty after he 'suddenly realised how nice it was to live in a country where people didn't come to your front door at 2am in the morning, and take you away and hand you over to people who've been specially trained to hurt you as much as possible'. His donation sparked a bright idea in Luff's brain for a bold new approach to fund-raising: a high-profile comedy event, featuring Cleese and the most illustrious of his fellow performers, staged in support of Amnesty on the imminent occasion of its fifteenth anniversary.

When Luff went ahead and called him, the comedian could hardly have been more amenable to his proposal. Cleese recruited his fellow Pythons, along with The Goodies and the former members of the Beyond The Fringe quartet (minus Dudley Moore, who was working at the time in America), as well as the likes of Eleanor Bron, John Fortune, John Bird, Neil Innes and Barry Humphries, while Luff found a London venue - Her Majesty's Theatre in Haymarket - willing to give up three free nights in April. Now entitled A Poke in the Eye (With a Sharp Stick), the tickets sold out within four days, and the media interest was intense.

This is where Martin Lewis first came in. Not only an existing supporter of the political cause but also active in various other comedy-related projects, he arranged to record the proceedings for a tie-in album. The result, also called A Poke in the Eye (With a Sharp Stick), sold very well, and Lewis was drawn into Amnesty's comedy team.

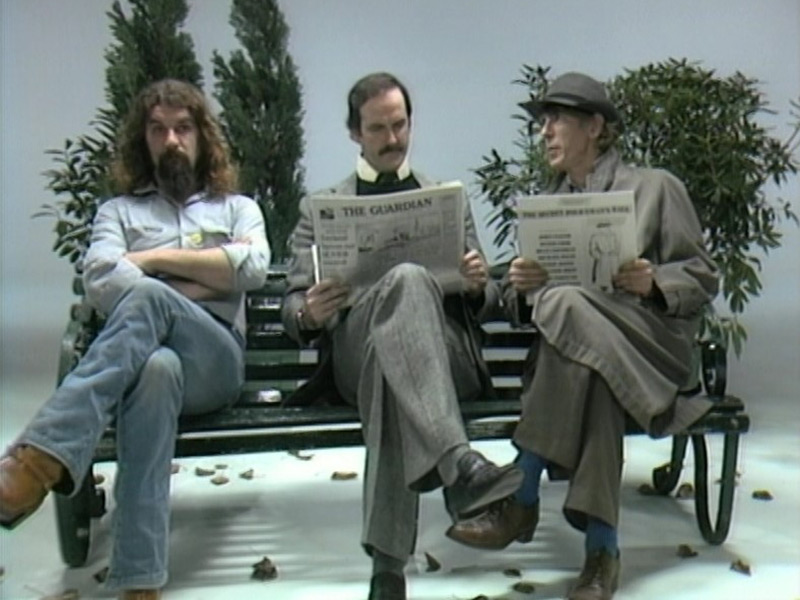

He was more involved the following year for the second event (which, as it was held at Sir Bernard Miles' Mermaid Theatre, was called originally An Evening Without Sir Bernard Miles, but would later be renamed by Lewis for the subsequent album The Mermaid Frolics). Relatively few comic performers (due to logistics or other commitments) were available this time around - Cleese committed, as did Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller and Peter Ustinov - and so Terry Jones, its director, was obliged to broaden the show's appeal (with the encouragement and assistance of Lewis) by recruiting some musicians to complement the comedy.

There would have been more of Peter Cook had it not been for Dudley Moore's unexpected no-show. 'Peter was absolutely livid', Lewis would later tell me. 'He thought it was really bad form, so he started drinking from the afternoon onwards, and by the time the show started he was in quite a bad way. Terry Jones was co-opted to play Dudley's part in a couple of routines - including the highly blasphemous "Bishop of the World" sketch, in which Peter was so oiled and still so angry about Dudley that he didn't care what he said, raging about sinners including "Diminished British people who go to 'Ollywood finkin' they're stars an' don't turn up for the fuckin' charity shows they're supposed to be performing at!," and he really made the audience gasp - but that material wasn't useable'.

Amnesty's collaboration with comedy was resumed, following a one-year gap, in June 1979 - one month after Margaret Thatcher's Conservatives became the new Government. The new show arrived bearing a brand-new name - The Secret Policeman's Ball - and a larger and increasingly diverse range of participants.

The driving forces behind these changes were Peter Walker (who had recently replaced the outgoing Peter Luff as Amnesty's Fundraising Officer) and his co-producer Martin Lewis. The problem was that, while the first couple of shows had helped increase awareness of Amnesty International by a staggering 700%, they had not raised much money for the organisation itself, so the intention now was to exploit the power of such events more consistently and effectively by making them bigger, more professional and much more marketable.

The first and most notable change came with the adoption of a brand name: The Secret Policeman's Ball. John Cleese, once the team had reconvened at his house in Holland Park, had wondered aloud as to whether they should name the next event An Evening Without the Secret Police - a suggestion that prompted Martin Lewis to shout out: 'What about The Secret Policeman's Ball?'. He expected Cleese to dismiss the idea, but instead the comedian immediately exclaimed: 'That's it! That's the title!'.

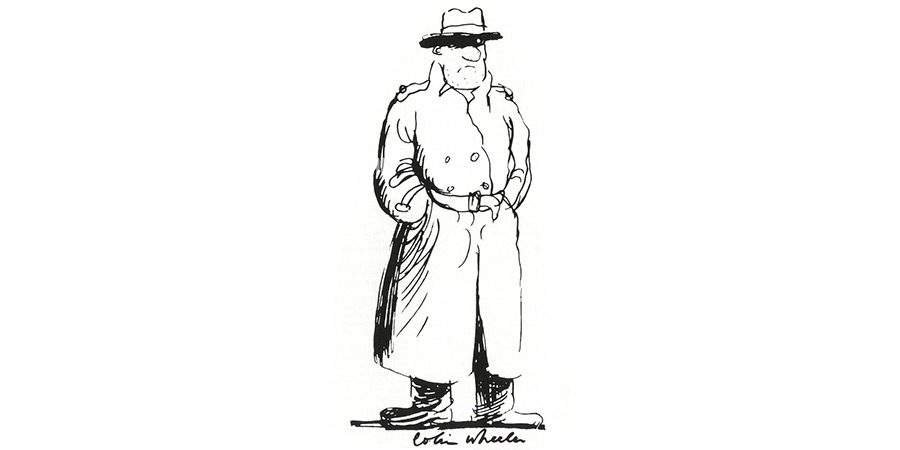

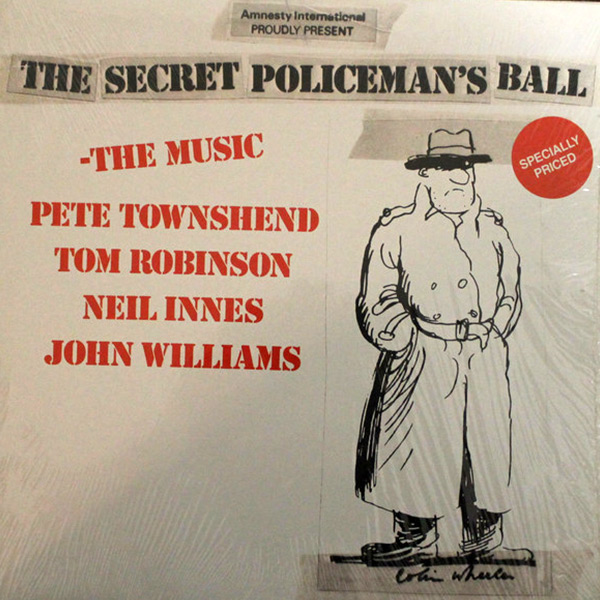

Peter Walker then commissioned the political cartoonist Colin Wheeler to create an iconic image to act as the show's logo - a shady secret policeman in a raincoat - and Lewis arranged for a graphic designer to surround it with titles set in a topical-looking Stasi/punk-style font. The SPB brand had thus been established.

Another change saw Walker and Lewis agree to start looking beyond the classic satirical generations of Cook and Cleese to supplement the cast with talent representative of a younger and broader section of Britain's comedy community, beginning with the twenty-four-year-old Oxford graduate Rowan Atkinson and the working-class Scottish stand-up comic Billy Connolly. It was Cleese who suggested the smart and versatile Atkinson, having seen him recently in revue at London's Hampstead Theatre, while Lewis added the joyously coarse Connolly, the first participant from a non-university background, 'to add richness to the palate'.

Lewis was also primarily responsible for another change: the introduction of music as an integral part of the productions. There had been the odd comic song in previous shows, and a few brief musical interludes, but Lewis (tapping into his network of connections within the record industry) now wanted to use rock and pop stars to play a role alongside the comedians.

He knew that an elective affinity between the two professions was already in existence. 'In those days', he later said, 'it was certainly the case that many rock musicians wanted to hang out with comedians and vice-versa. And the audiences certainly converged as well. Admirers of Monty Python, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore were usually also fans of The Beatles, Stones, Who and Kinks. So I was pretty confident the combination would gel'.

'John Cleese wasn't too keen on the idea', he would tell me, 'mainly, I think, because John, alone among the Pythons, was the one least enamoured with popular music, but when I asked him he said, "Well, it's not my cup of tea, but if you want a song or two, go ahead, but you must be responsible for it". So I felt I had carte blanche to use music to complement the comedy'.

Lewis thus went ahead and enlisted the services of The Who's Pete Townshend (not only to play his first high profile solo acoustic set but also to perform a duet with the classical guitarist John Williams), and the new wave singer-songwriter Tom Robinson - who had recently had a hit with Glad to be Gay. 'We hadn't actually billed the musicians', Lewis later said, 'so when Pete and the others walked onstage, there was this incredible roar. It was all a great success'.

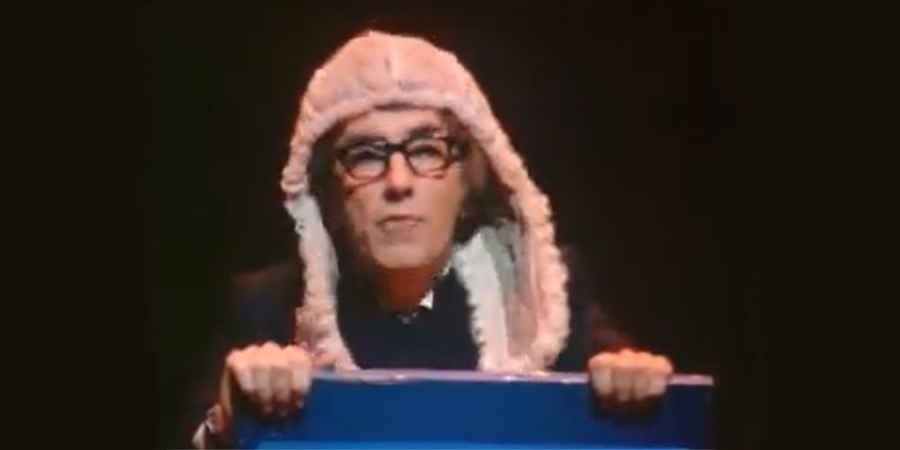

There was no doubt, however, that the biggest highlight was still a comic one: namely Peter Cook's brilliant parody of the startlingly biased summing up by Mr Justice Cantley in the recent Jeremy Thorpe trial, which ended up being entitled Entirely A Matter for You:

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, it is my duty to advise you on how you should vote when you retire from this court. In the last few weeks, we have all heard some pretty extraordinary allegations being made about one of the prettiest...about one of the most distinguished politicians ever to rise to high office in this country - or not, as you may think.

We have heard, for example, from Mr Bex Bissell - a man who by his own admission is a liar, a humbug, a hypocrite, a vagabond, a loathsome spotted reptile, and a self-confessed chicken strangler. You may choose, if you wish, to believe the transparent tissue of odious lies which streamed on and on from his disgusting, greedy, slavering lips. That is entirely a matter for you.

Then we have been forced to listen to the pitiful whining of Mr Norma St.John Scott - a scrounger, a parasite, pervert, a worm, a self-confessed player of the pink oboe. A man, or woman, who by his, or her, own admission chews pillows! It would be hard to imagine, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, a more discredited and embittered man, a more unreliable witness upon whose testimony to convict a man who you may rightly think should have become Prime Minister of his country, or President of the world.

You may, on the other hand, choose to believe the evidence of Mrs Scott - in which case I can only say that you need psychiatric help of the type provided by the excellent Dr Gleadle.

On the evidence of the so-called 'hit man', Mr Olivia Newton-John, I would prefer to draw a discreet veil. He is, as we know, a man with a criminal past, but I like to think - ho, ho, ho - no criminal future. He is a piece of slimy refuse, unable to carry out the simplest murder plot without cocking it up, to the distress of many.

On the other hand, you may think Mr Newton-John is one of the most intelligent, profound, sensitive and saintly personalities of our time. That is entirely a matter for you.

I now turn to the evidence about the money and Mr Jack Haywire and Mr Nadir Rickshaw, neither of whom, as far as I can make out, are complete and utter crooks, though the latter is incontestably foreign and, you may well think, the very type to boil up foul-smelling biryanis at all hours of the night and keep you awake with his pagan limbo dancing.

It is not contested by the defence that enormous sums of money flowed towards them in unusual ways. What happened to that money, we shall never know. But I put it to you, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, that there are a number of totally innocent ways in which that £20,000 could have been spent: on two tickets for Evita, a Centre Court seat at Wimbledon, or Mr Thrope may have decided simply to blow it all on a flutter on the Derby.

That is his affair and it is not for us to pry. It will be a sad day for this country when a leading politician cannot spend his election expenses in any way he sees fit.

One further point - you will probably have noticed that three of the defendants have very wisely chosen to exercise their inalienable right not to go into the witness box to answer a lot of impertinent questions. I will merely say that you are not to infer from this anything other than that they consider the evidence against them so flimsy that it was scarcely worth their while to rise from their seats and waste their breath denying these ludicrous charges.

In closing, I would like to pay tribute to Mr Thrope's husband, Miriam, who has stood by him throughout this long and unnecessary ordeal. I know you will join me in wishing them well for a long and happy future.

And now - being mindful of the fact that the Prudential Cup begins on Saturday, putting all such thoughts from your mind - you are now to retire - as indeed should I - you are now to retire, carefully to consider your verdict of 'Not Guilty'.

It was satire served hot off the skillet, as Cook had started his morning perusing a newspaper review of the first of the show's four nights, which claimed that the latest production 'lacked a sharp enough satirical bite', and had immediately slammed the paper down in anger and set to work on the new routine. 'He phoned me up immediately', Martin Lewis remembered, 'steaming about the review - "I'll show 'im fucking satire!" - and said, "I need you to get me a judge's wig, a gavel and a lectern..."'. A few hours later, he was ready to perform the routine as part of the show, although he was still adding to it and polishing it as he prepared to go on stage. No critic complained about a lack of 'bite' after Cook had finished that night.

The subsequent success not only of the show itself but also the new combination of music and comedy allowed Lewis to exploit the commercial appeal of the event far more extensively and impressively than ever before, staging numerous publicity stunts, packaging Roger Graef's film of the event for TV and theatrical release and also producing two separate records (an LP devoted to comedy and an EP to music) and a special twelve-inch single (Peter Cook's Here Comes the Judge) as money-spinning souvenirs. The Secret Policeman's Ball thus boosted Amnesty's finances as well as its public profile.

Walker and Lewis built on this breakthrough in 1981 with The Secret Policeman's Other Ball - which used the same template but showed even more ambition, employing more musicians and an edgier style of comedy. The aim now was to attract a much broader audience by offering a bold range of talents and tastes (to be filmed, at Lewis's request, by the young and fashionably unconventional director Julian Temple).

John Cleese began tackling the need for more women in the shows by recruiting Victoria Wood and Pamela Stephenson, and Peter Walker's search for a more controversial comic presence led him to hire the sharply intelligent and brilliantly aggressive Scouse stand-up comic Alexei Sayle. Martin Lewis declared a conflict of interest, as he was now managing the up-and-coming Sayle after being hugely impressed by his recent appearance at the Edinburgh Fringe, but Walker went to see Sayle in action for himself and (pronouncing him 'edgy' and 'just what we need') and agreed with Lewis that he should go into Amnesty's next show.

It was the musical aspect of the event that really epitomised the new sense of confidence at the heart of Amnesty's approach. Lewis first contacted George Harrison, but as he was still grieving over the murder a few months before of John Lennon, the former Beatle suggested that Lewis try his friend Eric Clapton instead. Once Clapton duly agreed, Lewis then pulled off another coup by teaming him for the first time with his fellow guitarist Jeff Beck. Building on the momentum, it was not long before Sting, Phil Collins, Bob Geldof, Midge Ure and Donovan had also been added to the bill.

The success of these musical acts had the unintended consequence of alienating Amnesty's original comedy patron, John Cleese. Already stressed by the need to control a show in which everyone seemed intent on over-running, the added problems caused by the musicians (and some of their 'refuelling' activities) further soured his spirits. 'Up until that point', Lewis would later explain, 'the backstage atmosphere had been pretty much like a cloistered environment at Cambridge or Oxford, and John had been among his peers and his friends. Now, however, there were roadies, technicians, managers and rock and roll entourages, and the backstage was no longer just familiar faces from the comedy fraternity. So, for John, the cosy intimacy of the early shows, and much of the fun, had gone'.

The organisers, however, focussed on the bigger picture, and were delighted with the progress that had been made. The Secret Policeman's Ball had become an instantly recognisable brand, and a very profitable, as well as popular, series of events. Amnesty now had its own on-going cultural - and commercial - phenomenon (which would help inspire, amongst other cause-based concert events, Live Aid).

Lewis, however, continued to push for further progress by exploring the show's international potential. His first SPB music-only compilation, released in 1980, had sold fairly well in parts of the States (and acquired something of a cult status because of its unusual collaborations), so he then worked hard to build on its success.

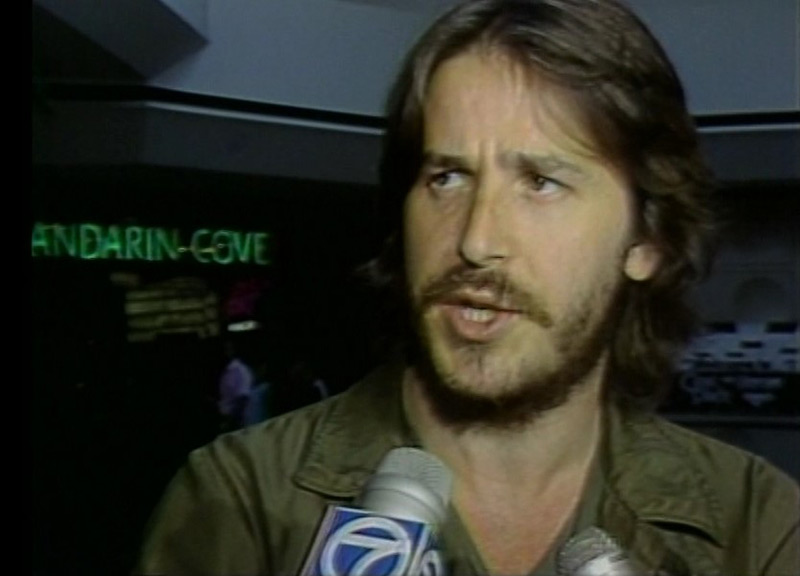

Armed with the footage from the past two events, he sifted through several ill-suited suitors ('I asked one guy, "Do you actually like Monty Python?" and he replied, "I love him - he's so funny!"') before deciding eventually to strike a deal with the recently-established distribution company Miramax. They decided to ask Lewis to distil the best bits from both UK films and distribute them in the US as a single feature-length movie under the title The Secret Policeman's Other Ball.

Lewis then proceeded to teach the American company a lesson in how to generate free publicity. He masterminded an ingenious marketing campaign, using Graham Chapman in a trailer and TV spot, which sold the film in the US while simultaneously mocking the then all-powerful Moral Majority that had helped secure both the election of Ronald Reagan and the boycott of Monty Python's Life Of Brian.

Calling his version of these self-appointed moral guardians the 'Oral Majority', and featuring Chapman in a sober jacket and frilly tutu demanding that the movie be banned 'before it turns us all into weirdos', Lewis planted advance stills in the New York newspapers and managed to get the TV spot banned by several fearful local stations - thus prompting plenty of priceless media coverage, culminating in an invaluable plug on the hugely popular network show Saturday Night Live (which had Chapman sit at a desk and make a solemn apology for causing any offence - before rising to reveal that he was wearing stockings, suspenders and Stars and Stripes underpants).

Released in the summer of 1982, the movie went on to be favourably reviewed by the critics - the influential Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times that the film contained 'some of the funniest sequences to found in any first-run movie at the minute' - and brought the concept of The Secret Policeman's Ball, and Amnesty, to a whole generation of American audiences.

Later on in the decade, Lewis - although now based in Los Angeles and no longer working regularly on the Balls themselves - helped promote Amnesty further in America and elsewhere when, along with Jack Healey (the Executive Director of Amnesty International's US division), he conceived and developed the Human Rights Now! world tour. Featuring Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Sting, Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman and Youssou N'Dour, with additional guest artists from each of the countries visited, it ran over six weeks in 1988 to great acclaim.

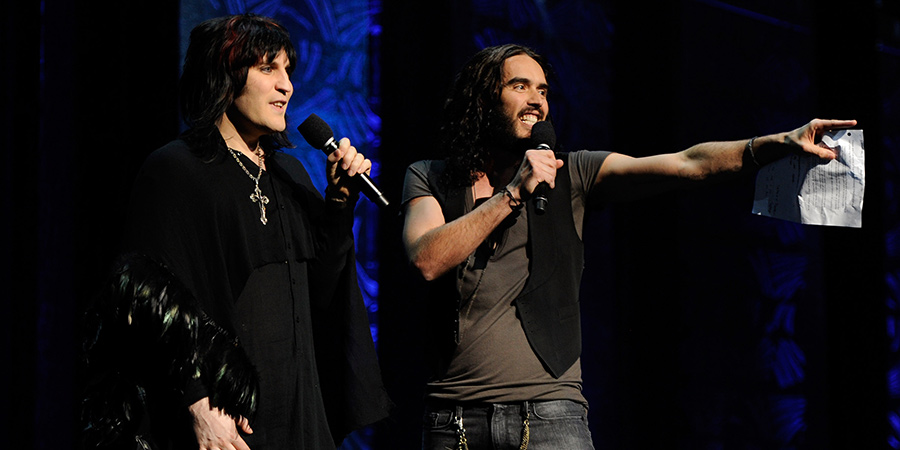

Lewis was back involved in 2012 when Amnesty UK (under the leadership of its latest Head of Events Andy Hackman) decided to revive The Secret Policemen's Ball brand to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the organisation. Held on this occasion at Radio City Music Hall in New York, it was now very much a global event, with all kinds of social media previews and live streams to accompany the actual concert.

Featuring a mixture of British and American performers - including Jack Whitehall, Ben Stiller, Russell Brand, Sarah Silverman, Eddie Izzard, Hannibal Buress, Micky Flanagan, Jon Stewart, Jimmy Carr, John Oliver, Rashida Jones, Noel Fielding, Stephen Colbert and Statler & Waldorf from The Muppet Show, along with the popular Burmese comedian Zarganar and such musical acts as Coldplay and Mumford and Sons - the cast was massive compared to the first couple of efforts back in the 1970s, but the sight of an overrunning Russell Brand being urged to 'wrap it up' provided a nice reminder that, even in a production as polished as this one, comedy will still bring a healthy degree of disorder to the proceedings.

Lewis helped organise (and write) some key video contributions from the likes of Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Eric Idle, excusing their absence on stage by claiming that both of their legs had recently been broken, badly replaced or had just dropped off. He also managed to pull off a typically audacious coup by persuading Robert De Niro - long before he became a familiar gurning face in car and sliced bread commercials - to film a follow-on sketch (co-written by Lewis and Michael Palin) that had him appear on a mock shopping channel ('Hi I'm Robert De Niro. You buyin' from ME?!') struggling to sell all of the legs ('The Python Leg-acy') that had fallen off various members of the Monty Python team (DE NIRO: 'Can I go now? Can I go?' TV PRODUCER'S VOICE: 'Err... we've still got Jack Nicholson's armpits...' DE NIRO: 'Oh for fuck's sake!').

It was a suitably memorable way for Martin Lewis to mark his thirty-sixth year of involvement in promoting the cause of human rights through comedy, and first pioneering and then mastering the production of national and international comic events. After all those years, and all those shows, he was still springing and inspiring surprises.

Amnesty itself, sadly and spitefully, would remove most of the details relating to Lewis's past achievements from its tie-in book commemorating its connection to comedy, A Poke in the Eye (With a Sharp Stick), which was edited, at least up to that point, by myself. Office politics sometimes trump, so to speak, office projects, and not all rights, it seems, are equal, after all.

What Lewis did contribute, nonetheless, in terms of originating and evolving something as special and influential as The Secret Policeman's Ball, merits him a place in the pantheon of Britain's most significant and successful comedy patrons and producers. When one adds to this all of his many other acts of advice, encouragement and innovation, in multiple spheres of the art, then he also, quite easily, wins a place in British comedy history as one of its most interesting and irrepressible characters.

See also:

Jack Hylton profile

Val Parnell profile

Lew Grade profile

Bernard Delfont profile

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more