One Lew Over The Cuckoo's Nest: How Lew Grade knocked entertainment into shape

Following on from the profiles of Jack Hylton and Val Parnell, here is the third article in this occasional series within Comedy Chronicles in which Graham McCann looks at the main impresarios involved in comedy over the past century.

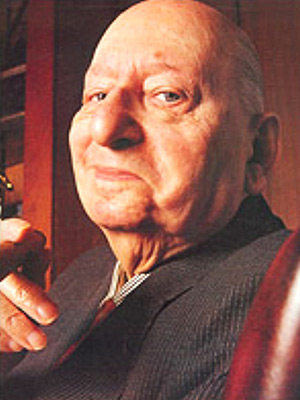

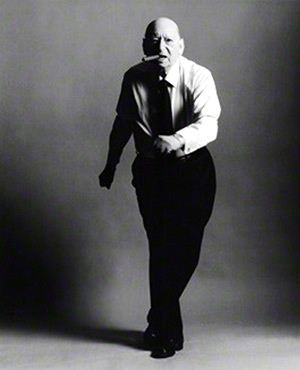

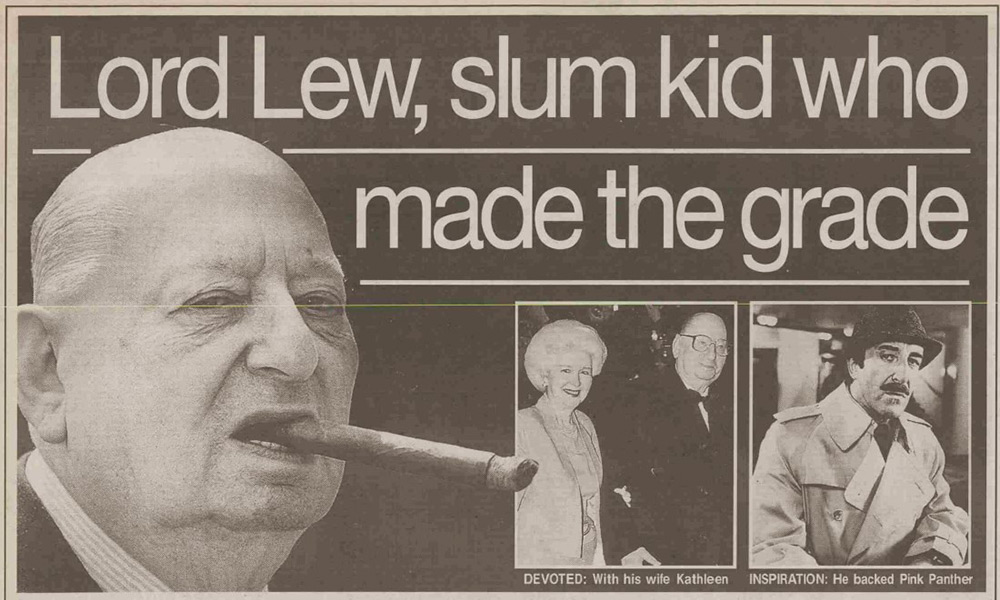

Like F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of Jay Gatsby, Lew Grade, as an impresario, 'sprang from his Platonic conception of himself'. Always brandishing his big cigar for the cameras, forever quick with a quote-friendly quip, and apparently ever-ready to announce some or other new and spectacular venture, he lived the life of a showman with all the conviction of a man who had captured his calling.

There were other impresarios around in his time, but only he seemed to embrace and embody the image with such gleeful ease. Jack Hylton - a short, stocky, white-haired, bespectacled man - brought to mind a contented northern mill owner. Val Parnell - tall, expensively-tailored, straight-faced and somewhat aloof - seemed more like a shadowy éminence grise.

Lew Grade was different. With his Hitchcock-like drone, Edward G Robinson mannerisms, and his Capraesque spirit, he looked, sounded and acted as though he had leapt straight out of an old Hollywood movie, a fictional media mogul mysteriously come to life. There were no chips on his shoulders; only, for a while, quotation marks. He played a role until the role became who he really was.

Born Lev Winogradsky on 25th December 1906 in the town of Tokmak, now part of Ukraine, he and his two younger brothers, Boris (later Bernard Delfont) and Laszlo (Leslie Grade) were taken by their parents to London in 1912 to escape the anti-Jewish pogroms that were still raging through Tsarist Russia. After leaving school at fourteen, he had a brief spell working for a clothing company before taking his first steps into show business as a dancer.

It has been said, many times (quite a few of them by the man himself), that he was crowned the 'World Champion Charleston Dancer' after a contest at the Royal Albert Hall in 1926. The great Fred Astaire, it is often added, was one of the judges.

This is one of those details that gets accepted and repeated over the years without anyone bothering to actually assess its veracity. If one does look into the matter, however, one finds all kinds of so-called dance 'world championships' being held in various parts of the globe at that time. Jim Sullivan was one of those crowned 'World Champion Charleston Dancer' in 1926, following a contest held in Chicago (Ginger Rogers came second).

There was indeed a Charleston contest at the Royal Albert Hall that same year, on 15th December, but it wasn't billed as a 'world championship'. It was merely called a 'Charleston Ball', organised by the theatrical impresario C.B. Cochrane (Fred Astaire, who was performing in London at the time with his sister Adele, was indeed listed as one of the judges), and the only names of the winners recorded by the national press appear to have been 'Mr Edward Greenhill and Miss Winnie Whitmee', 'Ronald Greene and Miss Winnie Newton' and 'The Plaza-Tiller Girls'.

Did Lev Winogradsky (or 'Louis Grad' as he started calling himself around about this time) win anything at all at this event? Possibly, possibly not. Was it an actual bona fide 'World Championship'? No, it seems not. Was this the first in a very long sequence of 'embellishments' by a crafty showman actively managing his myth? Yes, that seems rather likely.

What we do know without any real doubt is that, world title or no title, he was widely regarded as a very good Charleston (and black bottom) dancer at the time, full of energy, flair and invention. During the second half of the 1920s, he toured the international cabaret circuits as one half of a 'speciality' dance duo, with Al Gold, called 'Grad and Gold', who billed themselves as 'the dancers with the jointless legs', and claimed to hold (what else?) the world record for performing the fastest-ever Charleston.

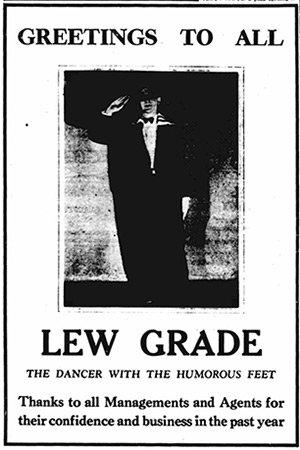

By the start of the next decade he was back as a solo act, now named Lew Grade, describing himself as 'The dancer with the humorous feet', and sharing the stage with such novelty acts as mind-readers, contortionists and 'Aussie' the boxing kangaroo. He formed another dancing double act a couple of years later, first with Anna Roth and later with Marjorie Poynter, until, by the middle of the decade, the years of 'high-speed dancing' took their toll on his knees (recklessly, he used to land on them, on rock-hard stages, as if they were mini-mattresses) and he was forced, more or less, to retire.

Still not quite thirty and desperate to stay in show business, he decided to become an agent (having already spotted and recommended numerous performers whom he had seen at close hand while on tour), going into partnership with Joe Collins (the father of Joan and Jackie) to form the 'Collins and Grade Theatrical and Vaudeville Exchange' in 1936. The breakout of war saw him drafted into the Army, but, once he was back in London, alongside Collins, he began to build the 'family business' with his two brothers.

First, in 1944, he teamed up with his brother, Bernard Delfont, along with a mutual friend called Alfred Zeitlin, to run their own agency called the United Film and Radio Exchange, and then, in 1949, he brought in his other brother, Leslie, to form another theatrical agency, Lew and Leslie Grade Ltd. In fact, from this time on, each one of them would start expanding their individual business interests and investments in all kinds of intriguing directions, often with the other two getting involved to some or other degree, to the point where the growing influence within the industry of 'The Grades' started becoming a subject of discussion and speculation.

The company run by Lew and Leslie certainly grew at a rapid rate over the next few years, swallowing up several smaller agencies in the process. They opened additional offices in New York and Los Angeles, brokered a lucrative deal with the General Artists Corporation of America (a major talent agency at the time) to manage their entire roster inside of the United States, and by the start of the 1950s they had established themselves as one of the main suppliers of talent for the prestigious London Palladium, run by Val Parnell for the Moss Empires Group owned by the Prince Littler family.

Lew, by this stage, had also established his image. Gone was the affable old hoofer; he had grown, quite self-consciously, into the role of the tough show business boss.

His wife, Kathie, had helped him, somewhat unwittingly, with the transition. Knowing that he had always felt nervous when dealing with big stars and their managers, she had bought him a box of large and expensive Montecristo cigars to offer his guests, hoping that it would help put him at ease. They remained unopened in the bottom drawer of his desk for a while until, one day, he wondered what it would be like to smoke one himself.

Lighting up, he took a couple of puffs, waved it around, sniffed the smoke, and found that he was enjoying it enormously. Then the phone rang. It was Val Parnell - someone whom Lew, like most people in the business, had always found intimidating.

Now puffing on the cigar, he felt himself relaxing. 'Yes Val,' he drawled self-assuredly, 'and what can I do for you?'

'That was the day,' he would later say, 'the real Lew Grade was born'.

Having made the grade in every sense of the word, he was now famous enough, and powerful enough, to have Jack Benny host a glamorous VIP-packed party for him when he visited Hollywood, he was producing shows as well as providing talent for them, and was starting to be treated like an equal by the other theatrical impresarios of the time. He had achieved what he had always wanted to achieve, was getting more of it all the time, and was looking forward to the rest of his life as one of British variety's major players. Then, however, came the challenge of television.

One morning during August 1954, Grade received a telephone call from an old American friend of his, an artist manager named Mike Nidorf. 'Have you seen The Times this morning?' he asked excitedly. 'I don't even read The Times,' Grade replied gruffly.

Nidorf proceeded to explain that applications were being invited for those interested in becoming programme contractors for the new commercial television. Grade was dismissive, saying, 'I've been hearing all about that - you've got to find three million. Where have I got three million?'

Nidorf said, 'If you can raise one million, we will raise the other two million'. When Nidorf went on to reveal that this 'we' to which he was referring was in fact the merchant bankers F.G. Warburg, it was clear that he was serious.

Now excited about the idea, Grade went ahead and called the most powerful British producer that he knew - Val Parnell. As always with Grade, once a light switch had clicked on in his head, there was not a shadow of doubt left lurking in his demeanour. 'Val', he exclaimed excitedly, 'we're in the television business!'

He proceeded to make the same announcement when he called the other heads he was hunting: Stewart Cruikshank of Howard Wyndham Theatres; Binkie Beaumont, the head of H. M. Tennants (the most important producers of plays in London); and Dick Harmel (the right-hand man to the wealthy South African businessman John Schlesinger).

Grade, in this sort of mood, was unstoppable. When Val Parnell called back to say that Prince Littler, the owner of Stoll Moss, was completely opposed to television (seeing it as a threat to the theatres) and thus would not allow him to become involved in any consortium, Grade went straight round to see Littler, and, after two hours of dazzling sales talk, convinced him that, rather than turn his back on progress, he should become part of it instead and join the others as an investor.

The consortium duly formed was called initially the Incorporated Television Programme Company (ITP), which then soon changed its name to the Incorporated Television Company (ITC). Little was chairman, and the other directors were Val Parnell, Stewart Cruikshank, J.A.L. Drummond (an associate of Warburg's), Philip and Sid Hyams (owners of Eros Films), the American public relations specialist Suzanne Warner, the broadcaster and entrepreneur Harry Allan Towers and Lew and Leslie Grade. They submitted their bid in September.

It failed. A campaign had been started among their competitors to thwart them, branding them 'The Show Business Octopus' because of the not-at-all implausible belief that, between them, they would have far too much control of the country's cultural talent. This spoiling strategy spooked enough people to undermine the assessment.

The group, however, was not going to give up, and they finally got their way when, in March of the following year, they merged with another consortium, the Associated Broadcasting Development Company (whose bid had been accepted for the weekday Midlands and weekend London franchises, but which was clearly under-capitalised). Their new combined company, called Associated TeleVision (ATV), had ABDC's Lord Renwick as its chairman and Val Parnell as managing director, with Lew Grade becoming his deputy.

ATV began broadcasting on 24 September 1955, and, right from the start, its strategy was shaped and strengthened by the partnership of Parnell and Grade. Both men knew all about the theatre, but were eager to immerse themselves in every aspect of television culture; both men had unrivalled access to talent on the variety circuit, but were also determined to find and fashion new talent specifically for TV; and both men brought an international scope to their broadcasting ambitions.

Between them they helped lead the way in terms of developing and directing commercial television for the next seven years. They expanded the range of genres and events on offer, they tried to find room for the prestigious as well as the populist, they made shrewd use of the experienced exiled Hollywood writers who had been blacklisted by the McCarthyite anti-communist witch-hunts (and who supplied the scripts for such successful series as The Adventures Of Robin Hood) and they made sure that they did more than punch their weight in the ratings.

It was an exciting, fluid, fast-changing period of progress. Only an estimated 190,000 sets had been capable of receiving ATV's programmes when they started in 1955; by 1957, the figure had risen to about 2.7m, with over £3m in advertising revenue having so far been banked. The channel's flagship soap, Emergency-Ward 10, which started in 1957, was reported to have doubled its national network audience, from 5m to 10m, in its first year on the screen. A random but fairly representative 'Top Ten' of the week's most-watched programmes, from January 1959, shows no fewer than five of the titles to be from ATV. The success story kept adding new chapters.

It helped, one ought to acknowledge, that one of the tabloids contributing to the writing of these chapters - The Daily Mirror - owned ten per cent of the company. Whenever one of its reviewers went rogue and dared to file a negative review (such as when Mary Malone suggested that the initials 'ATV' must stand for 'Awful Television'), Grade would be straight on the phone to the editor: 'Can't you control your own writers?' he'd rage. 'How can you do this to us - don't you know The Mirror has a big holding in the company?'

Most of the time, nonetheless, the broadcaster had no great need to bully the critics into penning some helpful praise. Plenty of its programmes were deemed to have deserved it on their own terms.

By the start of the 1960s, however, trouble was brewing in the boardroom. Val Parnell, though still exuding an all-powerful aura, had made many enemies (inside as well as outside ATV) with his autocratic manner, and the fact that he had recently been delegating or downgrading some of his duties, whilst being distracted by his seemingly insatiable desire for extra-marital affairs, had encouraged some to start arguing that the time was ripe for his removal as managing director.

Following a meeting of the other board members, it was Lew Grade, as his deputy, who was charged with the task of telling him it was time to go. Although Parnell initially refused, protesting that he was 'fireproof', he soon realised that, with most of his old support gone, his position was now untenable, and, at the age of seventy, he resigned on 26th September 1962. Grade, now aged fifty-five, promptly stepped up to take his place.

It seemed an abrupt and brutal process, an 'Et tu, Brute?' moment, as one leader moved the old one to one side. For the past seven years, Grade and Parnell had worked together every day of each week, facing each other behind their respective desks in the same big-panelled office at ATV House in Marble Arch. They had been on equal salaries, with the same share of the profits. They had been partners and, so Parnell had always thought, friends.

He would go on saying so in public. Acknowledging his younger colleague's apparent coup, he told reporters at the time: 'We're good friends and I'm delighted he is taking over'.

In private, however, Parnell would not sound quite so sure. The respect would still be there, and much of the affection, but some of the trust had gone. He never would know what exactly had gone on behind the scenes in order to oust him from ATV, but he suspected that Grade, after others in ATV's boardroom loaded the bullets in the gun, had not been as reluctant as he claimed to pull the trigger and take him out.

For his part, Grade continued to be fulsome in his public praise for the man he called 'the great Val Parnell'. Never actually an individual for Iago-like intrigues, he felt that all he had done was simply the same as Parnell had always done: seized an opportunity when it came to him. He moved on, therefore, with a reasonably clear conscience, by business standards, and a huge amount of ambition.

Now finally in charge of the operation, Grade proceeded to make himself arguably the most powerful and influential, and certainly the most widely recognisable, showman of his time. He stamped a personality on the brand, and struck the right poses and made the right kind of noises, calling for greater experimentation in television, the taking of bigger risks, and the full exploitation - commercial and artistic - of potential. Some of the bright promises and bold predictions would prove real, and some of them illusions, but, as he kept stabbing that big cigar up into the air while shouting out headline-friendly statements, the spells that he cast struck some as hypnotic.

He did, for television, deliver more often than not. During his reign at ATV the channel was a well-managed, and well-promoted, house of hits.

He did so, in part, by labouring away behind the image to be a smarter, swifter, and more personable manager than Parnell had ever been. He was more hands-on, he made sure the lines of communication were much shorter, and he not only trusted many more creative people but also - just as importantly - he made sure that they knew they were trusted.

His interests in entertainment were inclusive. He was no more drawn to comedy, as such, than he was to drama or music or game shows. What turned him on was talent - wherever he happened to spy it.

He happily showcased such comic personalities as Morecambe & Wise, Arthur Haynes, Benny Hill, Dave King, Bob Monkhouse, Sid James and Tony Hancock, as well as all-round entertainers like Bruce Forsyth and Des O'Connor. He embraced game shows such as The Golden Shot, soaps like Crossroads, pioneering consumer affairs programmes like On The Braden Beat, a few upmarket broadcasts under the banner of The Golden Hour (and personally went to extraordinary lengths to bring Maria Callas and Tito Gobbi to the screen singing an excerpt from Tosca) as well as maintaining the major mainstream ingredients of variety shows such as Sunday Night At The London Palladium.

Then there were the action, crime and mystery series, such as The Saint, Ghost Squad, Gideon's Way, Danger Man, Man In A Suitcase, The Baron, The Champions and The Prisoner and many more, along with contemporary sagas of the calibre of The Plane Makers and The Power Game and period dramas like Sergeant Cork. There were also, partly via Gerry Anderson's AP Films, a string of popular children's programmes, including Stingray and Thunderbirds.

There was not that much regional content, and some critics found the quality, at times, mediocre, but Grade's eye remained at all times on the prize of popularity combined with profits. One of his major achievements, in this sense, was to make his company start competing effectively internationally as well as domestically. At a time when British TV, in general, was still seen as being overly reliant on US imports, Grade led the way in reversing that trend, packaging more and more of his shows at least partly for the American market (receiving on several occasions the Queen's Award for Export for his efforts).

Aside from all the slick and stylish adventure series such as The Persuaders! (which he presented to a reluctant Roger Moore as a fait accompli: 'I've already sold it with you and Tony Curtis in the leads! The country needs the money - think of the Queen!'), and the variety shows such as The Piccadilly Palace and sketch series like Kopykats, Grade also oversaw the making of lavish transatlantic star vehicles for the likes of Tom Jones, Julie Andrews, Shirley MacLaine and Liberace. The fact that he pursued this policy to such impressive effect whilst sometimes chiding his ITV rivals (as well as the BBC) via the press for not being sufficiently 'British' in their output was a testimony to his remarkable mixture of shrewdness and bare-faced cheek.

Indeed, the personality cult that came to be created around Lew Grade during this era was not just inspired by all of the successes he enjoyed. It was also fed by the tales about all of the strange and unusual ways he had secured them.

The stories, for example, about his negotiating techniques were legion. Blessed by a thick skin and a short memory, Grade was not afraid to use just about any and every trick in the bargaining book if he thought it could help him win a deal.

He had, for example, the grifter's gift of the gab. 'One of Lew's great qualities', his colleague Norman Collins would remark, 'was that he could respond to things he didn't know anything about'.

He was also quite prepared to appear vulnerable and confused if he thought the impact of it would cause his opponents, in turn, to become even more vulnerable and confused. Once, for instance, he was present at a particularly heated meeting of all the ITV network bosses. As the voices became increasingly raised in anger, he suddenly started banging a gavel on the boardroom table while shouting, 'Mr Chairman! MR CHAIRMAN!!' It stunned everyone else into silence, until one of them, now utterly bemused, said, 'But Lew - you're the chairman!' He then got the others, still in a state of disorientation, to do exactly as he wanted.

Another crafty conceit once saw him pause a negotiating session that seemed to be in danger of falling apart, rise from his seat and stride out through a side door. The other party was left to sit on their own in the office while they overheard Grade mumble his way through what appeared to be a high-powered money discussion. Then he returned and said that he was pleased to announce that he had just managed to arrange a slightly better offer. It was only later, after the contract had been signed, that the other person discovered that the side door had actually led to a clothes cupboard, and Grade had been standing in there talking to himself.

Then there was the combination of his sense of the dramatic with his apparently complete lack of embarrassment when trying to drive home a bargain. 'He could pull out all the stops', Howard Thomas, his counterpart over at ABC, once revealed. 'Sentimental, threatening, pleading, admitting. His best act was when he would go down on his knees and fling out his arms, one hand still gripping his cigar'. Others who experienced such antics would liken it to finding oneself 'trapped in a Persian market' or plunged into 'a boxing match between heavyweights without a referee'.

There was indeed the odd occasion when Grade, rather than just let a deal drift away, would physically wrestle with a recipient in the hope of wearing them down. The movie director John Boorman, for example, would recall the time that Grade pleaded with him to direct a film about Dr Livingstone in Africa. 'He wrote a cheque for half a million pounds for me and, when I refused, he tried to stuff it into my pocket. I fended him off and we sparred for a moment. He deftly stuffed the cheque between my backside and the chair. I tried to ignore it. But I felt at a distinct disadvantage with half a million pounds of Lew's money sticking up my bum!'

In addition to all of this was a disarming charm, and playful good humour, that, when he wanted to use them, seemed able to tickle logic until it surrendered in a fit of giggles. 'All my shows are great', he would bark, as if doing an impersonation of himself. 'Some are lousy', he'd then concede, before adding with conviction, 'but all of them are great!'.

He could also, of course, be brutally ruthless when he felt the situation required it. The Beatles were among those who would end up attesting to this after Grade, always on the lookout for opportunities for expansion and diversification, slipped in to buy their publishing company Northern Songs from under their noses in 1969 (thus relieving them of their rights to over a hundred Lennon and McCartney songs).

Grade then used their desperation to end the draining legal battles with him to his and ATV's advantage. First, he pressured Paul McCartney into starring in an ATV show, James Paul McCartney (1973), as part of the star's exit deal. McCartney, rather pointedly, devoted a chunk of the undesired enterprise (billed as 'a personal project of Lew Grade') to a northern singalong inside a pub in Wallasey.

Then a seething John Lennon, still appalled at how much of his songwriter's earnings were going 'straight into Lew Grade's fat pocket', was similarly pushed into making a brief appearance at the fawning 1975 TV special in New York entitled Salute To Sir Lew - The Master Showman. He got through the event by sending out as many symbolic snipes as possible, from having his fellow musicians wear masks on the back of their shaven heads - 'a sardonic reference', he said afterwards in case anyone had missed it, 'to my feelings on Lew Grade's personality' - to performing a non-Northern Songs number mainly (as his lawyer of the time, Jay Bergen, would later confirm) so that he could snarl out the last line, 'I won't be your fool no more'.

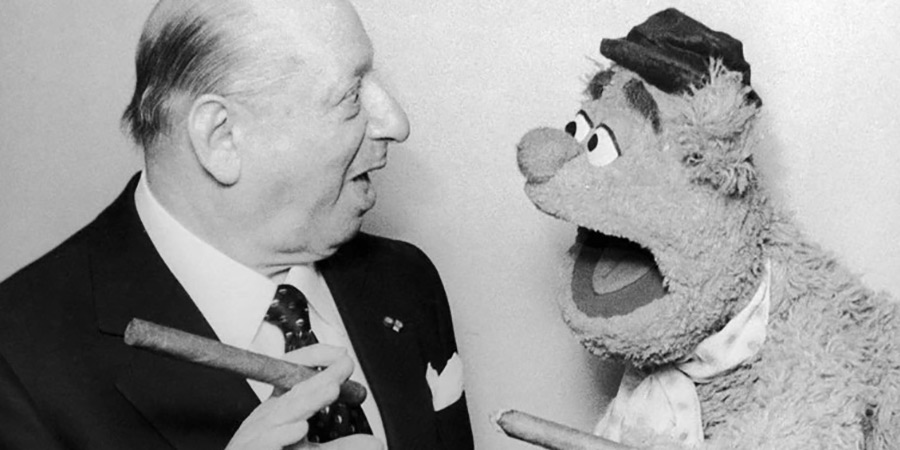

Grade, by this time, had tired to some extent of TV (as well as music). He still knew a good small screen project when he saw it - his production in the mid-1970s of The Muppet Show, for example, was a creative as well as commercial masterstroke, while the Franco Zeffirelli-directed Jesus Of Nazareth series won multiple awards and broke records in terms of international sales - but (having lost practical control of ATV in 1977 after reaching the directors' age limit of seventy) much of his time and energy was now being diverted (via ITC) towards the movies.

Claiming that he would be spending £50m every year making a dozen films, he would have his successes in this area as well. 1975's The Return Of The Pink Panther, for example, was a big box office hit, and a few more would follow, including The Boys From Brazil in 1978 and The Muppet Movie in 1979.

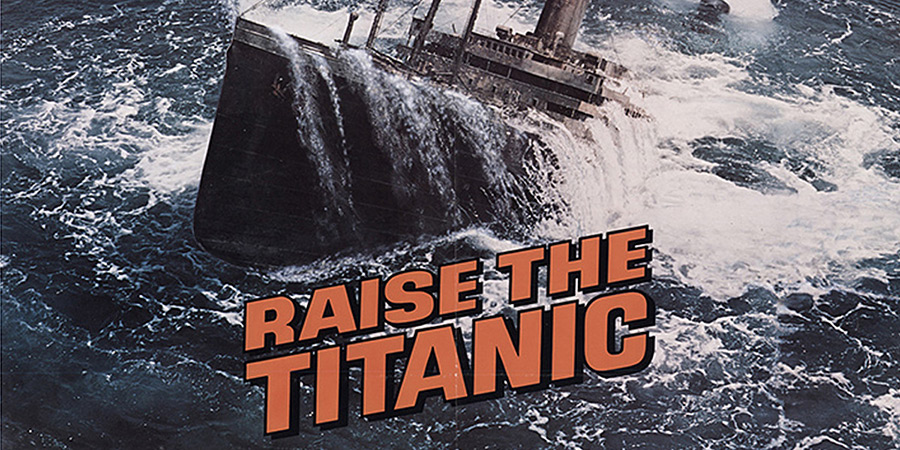

At the start of the next decade, however, his normally shrewd judgement deserted him when he committed to Raise The Titanic, a colossal failure which cost about £18m (twice its estimated budget) but earned only modest returns. 'It would have been cheaper', he said ruefully, 'to lower the Atlantic'.

Grade left ACC - ITC's holding company - in June 1982 after a series of protracted and increasingly bitter boardroom battles. Although it was announced by the new owners that he would remain in an unspecified 'special' executive role, he was quick to confirm that he planned to move on as a solo entrepreneur. 'The Lone Ranger', he told reporters, 'rides again'.

ATV had ceased to exist by this time, having lost its franchise earlier in the year to Central Television, but Lew Grade (who had been knighted in 1969 and made a life peer in 1976) was by no means finished yet. Within a day or so of leaving ACC he agreed a five-year deal to become chairman and chief executive of Embassy Communications International (an organisation with interests in television, cinema and home video). Now aged seventy-five but still very much the showman, he announced this news by performing a quick burst of the Charleston outside London's Inn on the Park Hotel as the cameras dutifully clicked. 'How do I feel?' he asked himself on behalf of the assembled reporters. 'I feel sensational!'

Three years later, in 1985, he joined the board of the famous Loews theatre chain in the US, and was also made the 'American entertainment consultant' to Coca-Cola after the soft drinks company swallowed up both Embassy and Columbia Pictures. 'You know what they say', he joked. 'Coca-Cola is the real thing - and so am I!'.

He then set up The Grade Company (not to be confused, at least ideally, with all of the other 'Grade Companies' that appear to have been out there) later that same year, and started investing in a number of multi-media projects, including co-producing Andrew Lloyd Webber's Starlight Express on Broadway. Returning to film production in 1987, Grade unveiled plans for a £100m package of family entertainment movies (which included a series of quaint but profitable adaptations of Barbara Cartland novels). He also found the time to join the supervisory board at Euro Disney.

The entrepreneurial energy, even now, was remarkable. His voice might have slowed to the speed of a vinyl album, but the brain still buzzed away at the speed of a single.

In 1995, he was delighted to come full circle when PolyGram, the Netherlands-based music and entertainment group, took over his old company ITC and invited him to return to it as 'Chairman for Life - Active'. 'I'm home,' he said, triumphantly.

Never losing the zeal for the deal, he continued working right up to the end (when asked what he would like for an epitaph, he suggested: 'I didn't want to go - and I'm not going!'). Having said on many occasions that he would retire in the year 2000, he almost made it. He died of heart failure, aged ninety-one, on 13th December 1998.

A sign of his distinctive stature as an impresario was how much warmth was wrapped up with the respect by which he was remembered. It was there in the tributes from his fellow executives - 'We've lost one of the most crucial figures in television in the UK', said the CEO of Carlton, Clive Jones. 'He was not only a great man - but a big one, generous and inspired. He understood popular, quality entertainment' - and it was there, too, in the many ones from his stars - Patrick McGoohan, recalling how The Prisoner got to be made ('I don't understand one word you're talking about', was Grade's response when the project was pitched. 'When can you start?') remarked, 'I can't conceive of anybody else in the world, then or now, giving me that amount of freedom'.

Of TV's trio of top impresarios, Lew Grade was probably the hardest not to like. He could be brash, rash, fanciful, stubborn, capricious, eccentric, ridiculously contradictory, exasperatingly devious and not always reliable with the facts, but he could also be courageous, generous, trusting, imaginative and innovative (as well as endearingly self-deprecating). He genuinely loved entertainment and the impact it can make - he truly wanted to thrill - and, whatever his faults, he always meant well both for the media he managed and the masses that they served.

He also, as far as comedy and all the other branches of the performing arts were concerned, tried to shape and show-off the very best that any culture could boast. 'I just love talent', he always insisted. 'I love talent of all kinds'.

Lew Grade didn't think in terms of 'high' or 'low', or 'posh' or 'common', or 'safe' or 'dangerous'. He thought only in terms of stars or potential stars, and good ideas rather than bad ones - and that is a lesson from which all of those involved in broadcasting today can, and should, learn.

See also:

Jack Hylton profile

Val Parnell profile

Bernard Delfont profile

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more