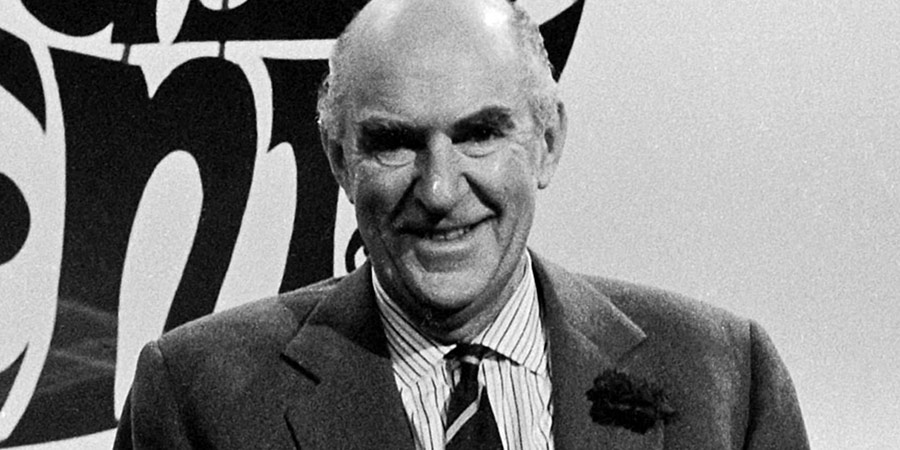

Horne, Solo: The incomparable charm of Kenneth Horne

It was a Friday evening, on 14th February 1969, when Kenneth Horne, all of a sudden, dropped down dead in front of more than seven hundred of his fellow celebrities. He was at the Dorchester Hotel in Park Lane, London, hosting a glamorous awards ceremony on behalf of Britain's Guild of Television Producers and Directors, and had just announced the winner of the 'Best Scientific Programme of the Year' when he collapsed and fell from the platform.

The politician Charles Hill, the current Chairman of the BBC Governors, was seated at the top table at the time. A former physician (he had been the nation's wartime 'Radio Doctor'), he got up and rushed to Horne's aid, arranging for him to be carried to an ante-room where an attempt could be made to resuscitate him. In spite of Hill's and others' efforts, however, there would be no response.

A visibly shaken Lord Mountbatten, who had been standing right by Horne's side at the time of his collapse, was left to complete the ceremony on his own in a room that was now totally and eerily silent. When it was all over, the planned celebratory ball was paused, the assembled orchestra stayed silent, and the distinguished guests began to depart, with many of them in tears.

As the news of Kenneth Horne's abrupt and premature death, at the age of sixty-one, started to spread, it was striking how profoundly his passing affected so many of his former colleagues, with even the more hardened among them being openly emotional in their expression of personal loss. 'I loved that man,' Kenneth Williams wrote that night in his diary. 'His unselfish nature, his kindness, tolerance and gentleness were an example to everyone'. Barry Took, one of Horne's regular scriptwriters, was similarly moved, describing him as 'one of the few great men I have met, and his generosity of spirit and gesture have, in my experience, never been surpassed'.

What might make the rare intensity of this reaction appear somewhat peculiar, at least to those who know little of Kenneth Horne, is that he was not a conventional comedy star. Neither a writer nor an actor, nor a teller of jokes, it is quite difficult to say what he did do, in a comedic sense, and yet, for many years, mainly on the radio, he was at the centre - the heart - of some of the funniest and best-loved shows of his era. How he got to play and grace this role is most definitely an unusual story.

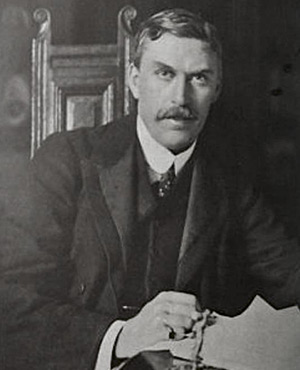

Born Charles Kenneth Horne in 1907 at Ampthill Square in London, he was the seventh and youngest child of Katherine Maria née Cozens-Hardy (the daughter of an eminent Liberal MP) and Silvester Horne, a non-conformist minister at Whitefield's Tabernacle on Tottenham Court Road. Silvester was widely regarded as one of the country's finest and most passionate preachers of his time, with even the likes of the young Winston Churchill revering him for his oratorical skills, and from 1910 until his early death in 1914 would also serve as Liberal MP for Ipswich whilst continuing his religious duties.

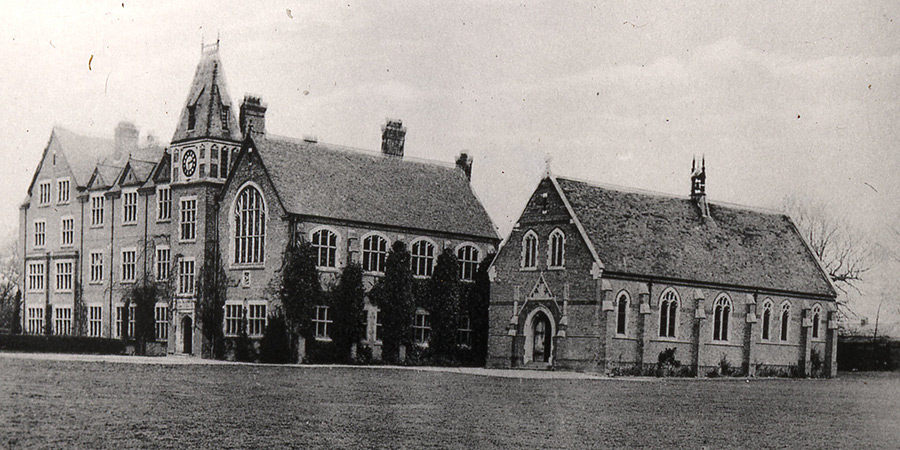

All seven of the Horne children (four girls and three boys) were sent as boarders to St George's School in Harpenden, where teachers took to addressing each one of them as numbers ('Horne I, Horne II,' and so on). When Kenneth, as the last of the seven, finally left, the school decided - either out of respect or relief - to commemorate its long connection with the family by naming one of its rooms ('the most repulsive room,' Kenneth would later say with a chuckle, 'you could possibly find') 'Horne Hall'.

Kenneth was never, to put it politely, a particularly able student, except when it came to sport. He dozed through the classroom lessons but came to life once out of doors and on to the playing fields. He excelled at every open-air activity on offer - cricket, rugby, tennis, athletics - while struggling to navigate his way through his written exams.

His mother, now widowed (Silvester having died in 1914, when Kenneth was just seven), worried about the ongoing academic under-achievement of her youngest son, and so in 1925 (pulling a few familial strings) she arranged for him to attend the London School of Economics (in those days still dominated by the lace hanky-to-the-nose bourgeois socialism of the Fabian Society) in the hope that it would prepare him for some kind of career in business. He studied under the guidance of some impressive figures, including Hugh Dalton (a future Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Stephen Leacock (who, apart from being a distinguished economist, was also an influential humourist), but Kenneth, once again, learnt remarkably little during their lectures (which, as he later put it brusquely, he found 'boring').

His formidable mother, nonetheless, was still not ready to give up, and in October 1926 she somehow managed, via the pulling of a few more strained strings (and with the vital financial assistance of his uncle, Austin Pilkington of the Pilkington glassmaking family in St Helens), to get Kenneth into the University of Cambridge, as an undergraduate of Magdalene College, to make a second attempt at mastering Economics. Once again, and even more so, he was privileged to be in the presence of some of the most eminent economists of the era, including John Maynard Keynes, Arthur Cecil Pigou, Dennis Robertson, Gerald Shove and Maurice Dobb, and, once again, Horne learnt very little from any of them.

Just like at school, Kenneth's days at Cambridge were all play and no work, with him committing himself to just about every sport available whilst dodging most of the supervisions to which he was sent. He represented his college at athletics, played rugby and tennis for the university, and also excelled at cricket, football and squash, while showing some further promise at golf and hockey. Academically, alas, he was notable only for achieving the rare feat of failing his (extremely basic) first year Qualifying Examination.

'He failed on every paper,' his furrow-browed tutor, Frank Salter, wrote to inform his mother, 'and his marks and his supervisor's report indicate a low level of industry'.

It was decided that he should sit the exam again the following October, but, displaying his usual careless inattention to detail, he got the date wrong and missed it. The faculty, after some heated in camera discussions, ruled that, as one final chance, he would sit the Part I exam in December, and would have to pass it or face being sent down.

He did manage, on that occasion, after much prodding from multiple directions, to turn up and take the exam. Once again, however, he failed it, and so was indeed sent down at the end of 1927.

His distressed mother now had to accept that her son was simply never going to succeed as a scholar. Any hope of a place being found for him in the family firm were also soon dashed, however, when the no-nonsense Austin Pilkington flatly refused to take on someone who had such a dismal academic record.

Pilkington did take pity on Kenneth to the extent that he arranged for him to have an interview with the soon-to-be-merged Triplex Safety Glass Company at King's Norton in Birmingham, but insisted that he would not give him a formal written recommendation and Kenneth would have to win them over entirely by himself. It would be to Kenneth's great good fortune, however, that the manager at Triplex turned out to be a remarkably kindly and fun-loving man who, after learning that Horne had no qualifications but enjoyed pretty much every kind of sport, exclaimed: 'I think you're just the chap I want - start on Monday at thirty bob a week!'

Things started, at long last, to go well for Horne once his training began. In 1930 he married Lady Mary Pelham-Clinton-Hope, daughter of the 8th Duke of Newcastle (the relationship would be short-lived, ending in divorce two years later; he would marry twice more, first in 1936, to an old girlfriend called Joan Burgess, and then, when that union ended in 1945, to a war widow named Marjorie Thomas). Now showing an unexpected commitment to business, he started to impress at work and his income, as a consequence, began to rise at a rapid rate.

His second career in comedy only came about by accident. In 1938, with escalating international conflict judged imminent, he had enlisted in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, and, during the early months of the subsequent war, he was drawn into being involved with the local concert party. Having inherited from his father a love of wordplay, he wrote a few light-hearted limericks and monologues and, though limited in his abilities as a performer, found that he enjoyed entertaining his colleagues and listening to their laughs.

Early in 1942, the BBC producer Bill McLurg invited the RAF station at which Horne was based to host an edition of his twice-weekly armed forces programme (a rag-bag of serials, quizzes, talent contests and music 'for and by Anti-Aircraft and Balloon Barrage personnel') called Ack-Ack, Beer-Beer. Horne (who by this stage had risen to the rank of Squadron Leader) was tasked with hosting the show, making his broadcasting debut on 16th April.

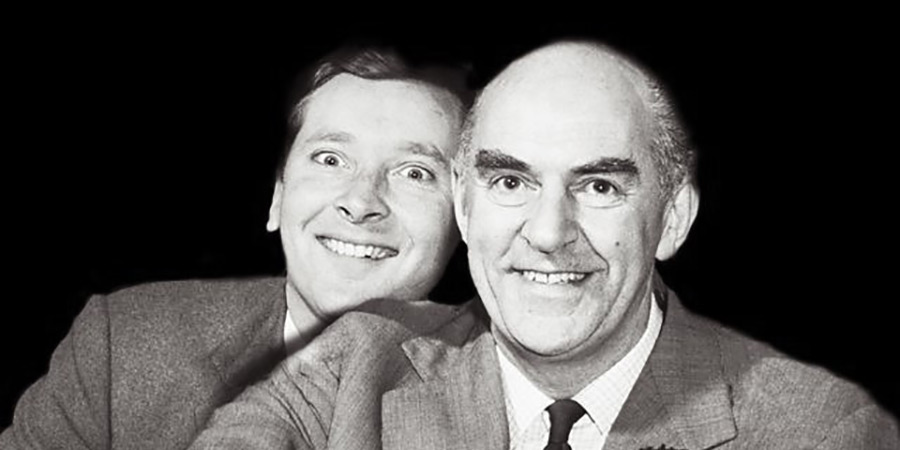

McLurg was sufficiently impressed by Horne's deep speaking voice and smooth style of delivery that he signed him up as the show's resident quiz master, and soon Horne was being used by the BBC for several other forces' broadcasts. It was through these multiple activities that he came into contact with Flight Lieutenant Richard Murdoch, who was already well-established as a radio comedian.

Finding that they had much in common (they came from similar family backgrounds, had been contemporaries at Cambridge - although, as far as anyone has so far confirmed, had not known each other there - and carried into comedy the same easy-going Corinthian spirit), the two men soon formed a friendship that led eventually, in 1944, to them co-starring in the sitcom Much Binding In The Marsh. It would be a partnership, and a project, that pushed both men forward.

Set in a fictitious Royal Air Force station, Horne played a well-brought-up but dim-witted officer with Murdoch as his chronically harassed second-in-command. It was an appealingly jolly affair, poking gentle fun at authority in much the same way (but with far less of a satirical snap) that their sister show, written and starring the more artfully subversive Eric Barker, would do for (and to) the Navy.

As popular though the show would prove itself to be (attracting audiences of about twenty million at its peak), once the war was over, and Horne demobbed, he returned without much prior thought to working full-time again at Triplex, and was soon promoted to the position of sales director. He still appeared alongside Murdoch every now and again on the wireless, and enjoyed the broadcasts greatly, but now, in peacetime, regarded radio as nothing more than an enjoyable hobby.

Delegating more as his authority expanded, he took on a growing number of broadcasting commitments later on in the decade, most notably with the long-running radio parlour game Twenty Questions, but business remained his priority. He was a clear-thinker, an excellent problem-solver, he liked overseeing things, and he most definitely enjoyed the profits that came his way.

In 1954, after spending twenty-seven years at Triplex, Horne, tempted by a bigger wage and a smaller workload, accepted the position of managing director of the British Industries Fair, travelling widely to promote foreign interest in home-grown goods, and then in 1956 he moved to the post of chairman and managing director of the toy manufacturers Chad Valley.

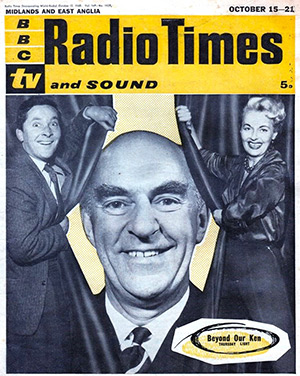

It was at the start of 1957, however, that Horne's 'hobby' really started to compete with his business for his time and energy. Aside from Chad Valley, he was by now serving as chairman of no fewer than five other firms, as well as holding directorships in several more, but (after being tempted by various BBC producers) was also about to start working on his own radio show. The pilot episode of Beyond Our Ken, which the writers Eric Merriman and Barry Took created expressly as a vehicle for him, was well enough received for the BBC to commission a series, which was scheduled to start in April of the following year.

It was at this point that his life, which now seemed so bright, was suddenly plunged into darkness. In February 1958, Horne, following a long and draining boardroom meeting, while being driven home, suffered a debilitating stroke and ended up totally paralysed down his left side and lost the power of speech. 'It was,' he would say, 'a complete full stop for four months'.

'It seemed like the end of the world for me,' he would later say. After a brief period of depressed resignation, however, he found the desire to start fighting back.

After undergoing a draining course of intensive physiotherapy, along with plenty of sessions with a speech therapist (whose recuperative techniques included making his patient pick up pieces of paper by sucking at them through a straw), Horne was able eventually to move and speak again (albeit, as anyone else who has gone through such things will know, the thought of the horror returning would always haunt him). Doctors warned him, however, that, unless he found a way to drastically reduce the mental and physical strain that the combination of his two careers was causing him (working, as he put it, 'twenty-five hours a day'), then he would probably not live much longer.

'So,' Horne later explained with more than a little self-editing, 'I decided on the spot, then and there, to give up any business connections that I had and concentrate on broadcasting, and see if it would be kind to me and enable me to lead a reasonable life'.

Beyond Our Ken, as the first step in his singular new career, then went ahead. He supported himself as discreetly as he could with a walking stick for the first three broadcasts, but then declared, 'I'm not using this anymore,' and threw it away. He had to knock the leg hard that was still numb in order to enable him to stand up and go out on to the stage, and he would walk with a noticeable limp for the rest of his life, but gradually his health further improved, and he came to realise that, with only radio now on which to concentrate, he was actually happier than he had ever been.

It helped that the show - and its successor, Round The Horne - handed him a kind of second family for support. Kenneth Williams, Hugh Paddick, Betty Marsden and Bill Pertwee (along with their self-mocking announcer Douglas Smith) became great friends as well as colleagues, while the writer Barry Took eventually looked on Horne as a second father. 'We all adored him,' Betty Marsden would say. 'He was a marvellous man'.

This, however, brings us to the odd thing about Kenneth Horne. As he himself - the most modest of men - freely admitted ('I never looked upon myself as an entertainer'), it was the others who were supplying all of the funny voices ('Between them Betty, Ken W., Hugh and Bill Pertwee can provide at least 100 voices, and if you take me into account the figure leaps to 101') and, as Betty Marsden later acknowledged with great affection, it was the others who were doing all of the comic acting ('The idea of [him] acting in front of people, well, he would have gone mad!'). What, then, did Kenneth Horne actually contribute to his own hit show?

The main answer is: he served as a straight man to all of the comedians. Jack Benny had done the same on his own US radio and TV shows: unlike Horne, Benny was also a genuinely great stand-up comic, but, very much like Horne, for his own show, he was happy to serve mainly as the door for others to push against: to be the stooge, the cue, to set up the comedy and let everyone else get the laughs. It was a role that demanded exceptional discipline and great timing, as well as a rare generosity of spirit, and both men - Benny and Horne - met and kept those high standards remarkably well.

In Kenneth Horne's case, his limitations as a performer were actually part of the reason why he was so effective for his own show: he was the audience's representative on a stage full of eccentrics, the one fixed easily-believable personality in a world full of whacky shape-shifters, a vulnerably sane person surrounded by indomitable lunatics. Take, for example, whenever he stepped hopefully, trustingly, into a Julian and Sandy sketch, like a fluffy puppy wandering into a lion's cage, and took every punchline on the chin:

SANDY: Well, Mr Horne! How nice to vada your dolly old eek again! What brings you trolling in here?

KENNETH: Can you help me? I've erred.

SANDY: Yeah, well, we've all erred, ducky. I mean it's common knowledge, innit, Jules?

KENNETH: Will you take my case?

JULIAN: Well, it depends on what it is. We've got a criminal practice that takes up most of our time...

KENNETH: Yes, but apart from that, I need legal advice.

SANDY: Oooooh, innee bold? BOLD, though?! Ooooh: 'time has not withered nor custom staled his infinite variety'! Ha-ha-ha-ha-haaaa!

JULIAN: Just a minute - what is it that you've done?

KENNETH: Well, um...no, I don't like to say.

SANDY: Oh, come on!

JULIAN: Come on, you can tell us - we've handled the most bizarre briefs!

KENNETH: Well, look, it's here on this charge sheet.

SANDY: Let's have a varda...Ooooh, Jules, look at this!

JULIAN: Oooooh! He didn't?

SANDY: He did! It's written down!

JULIAN: In broad daylight?? Outside the corner house??? Aren't you ashamed????

KENNETH: Yes, but it was only a parking offence.

SANDY: 'Only'? They're very hot on that! What do you think, Jules?

JULIAN: Well, let me look up me tort...

It was much the same with his regular chats with the hyper-sensitive Australian feminist and pioneering sensitivity reader Julie Coolibah, where, mostly inadvertently, he set up one double entendre after another:

JULIE: I've notified the police where I am - so watch it!

KENNETH: Watch what? - oh, I'll rephrase that. Now, what are you worried about?

JULIE: Well, for all I know, that may be a two-way mirror, with a hidden camera behind it, recording my every movement so you can gloat over 'em later!

HORNE: I wouldn't dream of such a thing!

JULIE: Oh, are you some sort of puritan, then?

KENNETH: Now, look, let's get on with it - I mean, let's continue the interview, that is. I understand you've left your last job?

JULIE: Hah! Too right, Bluey! That office was full of obscene calendars. With no pictures on 'em!

KENNETH: Pardon?

JULIE: They're the worst kind! 'Cause you know what the pictures would be if they had any?!

KENNETH: Yes. I hadn't thought of it that way.

It worked just as well with all of the spoof routines he would part-narrate and part-participate in, such as this James Bond parody:

KENNETH: Suddenly, he pressed a button concealed in his waistcoat and a secret panel in his kimono slid open. Out of it stepped a beautiful girl in thigh-length boots and a bikini.

BETTY: You know all about me, I think, Mr Horne.

KENNETH: Pussy Galore?

BETTY: I've never had any complaints.

Horne could also be relied on, thanks to his reassuringly sober BBC voice and respectable Establishment persona, to smuggle through plenty of saucy or subversive material himself, with unforced faux innocence, that might otherwise have seemed too obviously questionable to the censors. 'I'm all for censorship,' he would say. 'If ever I see a double entendre, I whip it out'.

His sober 'announcements,' usually at the start of each show, were particularly good at how they got the audience in an appropriately suggestive frame of mind:

And now for the answers to last week's questions. 'Complete the following song titles. Question One: "Walk right in, sit right down, and..."?' The answer is: 'Baby let your hair hang down'. Now, many of you wanted to walk right in, sit right down and do something else entirely. In fact, what a 'Mr Gruntfuttock of Hoxton' wanted to walk right in, sit right down and do is not only physically impossible but also extremely dangerous to passers-by.

The one other invaluable thing that Horne did was to provide an appealingly pivotal personality that would ensure that the show never fell apart, because he was always there as the centre that always held. The writers thus knew that they could be as disparate and daring as they wished with their expanding range of sketches - going, say, from a parody of old romantic movies to a send-up of a current TV commercial to a surreal South Seas fable to a seemingly obscene phone call to one of Rambling Syd Rumpo's comic songs - and the urbane Horne would always provide the invisible stitching with his reassuringly coherent narrative links.

He used his old skills as a chairman and managing director to nurture one (or, to be more accurate, two) of the great radio shows of that or any other era and turn them into a national broadcasting success. He collected and organised the talents, he delegated selflessly and shrewdly, he knew when to intervene and when to hold back, and he kept a sharp focus on the big picture.

It was all done with such a lightness of touch that every element and connection seemed organic, and the show flowed from one week to the next with such an unforced and all-embracing sense of fun. What made his achievement even more impressive, however, was the fact that he was also a genuinely likeable individual; there was a warmth to the programme, as well as an infectious sense of mischief, thanks to the man who was its motor and master of ceremonies.

In 1968, with Round The Horne still hugely popular on the radio after four series, Horne (his old commercial instincts sufficiently intrigued) agreed to adapt the basic format for television. Horne A'Plenty, which would be broadcast on ITV, had one of the same writers in Barry Took, although with different actors in support (Graham Stark, for example, took some of the parts that would have suited Kenneth Williams, while Sheila Steafel did the same for most of the Betty Marsden-style roles). Most critics found it too awkward a hybrid (with one declaring meanly that it, along with Horne himself, 'should be heard, not seen'), but, nonetheless, it found a solid enough audience, ran for two series, and, like Round The Horne itself, would have continued had it not been for its star's sudden death.

That death came about, at least in part, due to a tragically irrational decision taken by Horne himself. He had suffered a major heart attack late in 1966, and, although he went to great lengths to hide the true nature of his condition from both the BBC and his fellow performers (assuring them that it was merely a bout of pleurisy), he was still unable to work for the next three months, only returning the following year to make the third, delayed, series of Round The Horne.

His personal physician, who had prescribed him daily anticoagulants and blood pressure pills, now urged him to slow down and find more time for rest, but, if anything, Horne did the opposite, supplementing his existing radio work (which, aside from Round The Horne and Twenty Questions, included the quiz show Top Firm, Housewives' Choice, Sounds Familiar, World Quiz and many readings for Woman's Hour) by also extending his involvement in television, not only with his own new Thames TV show but also several other current and up-and-coming commitments, including hosting a succession of quiz shows for Southern Television, along with a regular role as one of the team captains on the BBC's Call My Bluff.

He did go to a health farm in a bid to get fitter, but, just like in his old university days, the instructions he was given, no matter how logical or well-meaning, failed to stick for too long in his head. 'He didn't do "ill" very well,' his wife would later reflect. He preferred to keep a stiff upper lip, live for the moment, and simply pretend that nothing was wrong.

There was perhaps a sense in which he was trying to block out a bleak feeling of destiny. Heart problems, after all, were congenital in his family: his father had died of heart failure at the age of just forty-nine; his eldest brother had been struck down by the same disease at fifty-one; his eldest sister at the age of sixty-five. Kenneth, at that stage, was fifty-nine. There were moments and moods, it seems, when a sense, in private, of helplessness, and hopelessness, almost overwhelmed him.

Activity, therefore, was his therapy, his means of fighting against the fear. So long as he had positive things to preoccupy him, the negative thoughts were kept repressed.

By the time that the fourth series of Round The Horne had started, in February 1968, the battle was becoming harder for him to fight. Even though he was driving himself on with yet another brave show of warmth and positivity, it was clear to his colleagues that he was getting frailer, and there were times, as the recordings went on, when he was growing alarmingly grey in the face. Never one to stop and discuss such matters openly and directly, Horne continued to push on as if nothing was wrong, slapping his stiff left leg roughly into action when moving for his cues, while the rest of the team made sure, discreetly, that a chair was always kept close to him, and a drink was always placed in reach.

The frustration with his failing energy, however, was depressing him, and, out of a sense of quiet desperation, he began to explore alternative remedies. He didn't want to stop. He was desperate to keep on with the fun.

In December of 1968, in search maybe of magic, the fateful time arrived when he met with a faith healer. This man - who has never been named - advised his new celebrity client to 'free himself' from any dependency on conventional medicine and find good health purely through the power of positive thinking.

Horne, who had never liked feeling reliant on any external aids (the walking stick, after his stroke, had been ditched against his doctor's advice, and his radio team even had to keep devising polite ways to persuade him to put his glasses on for script readings), foolishly agreed to the advice. Without ever informing his physician, he promptly dropped all of the prescribed drugs.

Just three months later, thanks to this wildly irresponsible instruction, Kenneth Horne would be dead.

There were no obvious signs of what was to come when he arrived early on that night at the Dorchester. Having convinced himself that the new strategy was working ('the "good times" seem to be getting longer,' he had recently assured a friend), he was in his usual good spirits, his deep, rich and fruity voice strong and sure, as he kept the VIP audience amused in between announcing and presenting each category.

Midway through the stellar occasion he was particularly pleased to present the 'Best Comedy Script' award to none other than his own two writers and proteges, Marty Feldman and Barry Took, for Feldman's TV show Marty. After embracing them both warmly and watching them head off back to their seats, he leaned into the mic proudly and said, 'These chaps got an award last year for Round The Horne, which is coming back on Sunday, March 16th, with a repeat the following day. So don't forget to listen!'

The audience laughed at the impromptu plug - quite a cheeky thing to have done in those days - and Horne moved on to announce the next nominees. It was then when the thing, the awful thing, happened. He swayed slightly, murmured something breathily, and then suddenly crumpled in pain, fell three feet down from the podium, and was dead before he hit the ballroom floor.

A horrified Took and Feldman, only a few seconds since hugging him, now found themselves cradling him, helping to carry their dear friend and patron into the adjoining bar for emergency treatment. After Lord Hill's and others' frantic efforts to perform CPR had failed to get any response, another doctor who had now arrived tried the kiss of life, but to no avail. Kenneth Horne had, they realised, already gone.

When Horne's personal physician learned of the poor informal (but expensively priced) advice that had led to his patient's death (the autopsy had described the state of his blood as 'like treacle'), he was understandably angry and appalled. 'The poor silly fellow,' he exclaimed. 'If only he'd listened to me, he could have had another ten years!'

The scripts for the now-aborted fifth series of Round The Horne would be adapted to form the basis of a new series, starring Kenneth Williams and featuring support from his fellow Horne stalwarts Hugh Paddick and the announcer Douglas Smith, called Stop Messing About!. Williams, once the show had steadied after a shaky start, tried to convince himself that it might reach the peaks of its predecessor, describing it in his diary as 'a triumph in the face of the terrible adversity of KH's death,' but in truth, without Horne, it lacked a heart.

The tributes, immediately after Horne's death, kept on coming. Huw Wheldon, the BBC's Managing Director of Television, said: 'I am deeply sorry. I knew him well. He was a hell of a good chap, a magnificent professional'. That same sentiment was echoed by many others: Kenneth Horne had indeed been, everyone agreed, 'a hell of a chap'.

A memorial service was held for him on 12 March 1969 in London at St Martin-in-the-Fields Church in Trafalgar Square. There were many more tears, but, as the event went on, even more laughter, because, it was agreed, he had been responsible, in his own distinctive way, for bringing so much of it into other people's lives ('If I ever knew a gentleman,' the journalist Paul Jennings reflected, 'it was Kenneth Horne. [...] He gave you his whole attention, his whole courtesy. And what a courtesy it was!'). The following month, a weeping Betty Marsden, on behalf of Horne's widow, accepted his posthumous award as the Radio Personality of the Year.

She stood and held the prize while the audience applauded. She couldn't speak; she could only smile.

One obituary, in The Sunday Mirror, judged him 'perhaps the last of the truly great radio comics,' which takes us back to reflecting on the enigma that is Kenneth Horne. In a strict sense, he was not really a 'radio comic' at all, let alone a 'truly great' one, but, nonetheless, we can still appreciate the observation, and go some way to making it make sense.

What he actually was, one might argue, was one of comedy's great facilitators, the conductor who enabled the orchestra to soar. One could, in fact, go a little further, in search of precision, and settle on him being proclaimed, in a comedic sense, sui generis: for what Kenneth Horne did was not only wonderfully generous and charmingly effective, but also, quite simply, unique.

We will always miss him for that reason. There simply wasn't, and isn't, anyone else quite like him. Kenneth Horne was an irreplaceable comic friend.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more