A road less travelled: John Le Mesurier and The Culcheth Job

John Le Mesurier liked to describe himself as a 'jobbing actor'. He even chose the phrase as the title of his autobiography. Famously laid-back though he was, he lived in fear of being laid-off, and so, whatever he might have thought about certain offers of employment, when left to his own devices he almost always accepted them.

This was not, for a long time in his career, all that easy for him to do, because his agent, unlike him, was notorious for being extremely, and rather eccentrically, picky. This agent's name was Freddy Joachim.

Freddy Joachim was a legendary figure in the world of theatrical agents. The son of an immigrant Jewish stockbroker, he was an accountant by training, and had moved into show business at the start of the 1950s without ever losing the misgivings he had about many aspects of its manners and milieu.

A stocky, prematurely silver-haired and self-consciously well-spoken little man who was dogged throughout his life by an acute inferiority complex, he sought the false sense of security that was offered by old-fashioned snobbery. He thus affected a degree of respect for the 'legitimate' theatre, or at least for those playwrights associated with it whose work he thought he ought to like, while accepting that the cinema, at its biggest and best, was not something at which he should audibly sniff, but that, as far as positives were concerned, was about it. The rest of the modern media was treated by Joachim with an undisguised sense of snooty disdain.

He owned neither a radio nor a television set, and was proud of that fact. He did deign to accommodate the former for a decade or so, only to part company with it, suddenly and very violently, in 1938, when he became so enraged by listening to the then-Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's appeasement speech (detailing his meeting with 'Herr Hitler' in Munich) that Joachim promptly picked up the set and hurled it straight out through his bedroom window.

If he felt obliged to watch a television programme for work purposes, he would only do so under very obvious signs of duress, and insisted upon the relevant broadcaster providing him with on-site viewing facilities so that his home would remain unsullied by the presence of what he suspected would be unbearably substandard fare. Once the ordeal was over, he would return to his house for a kind of cleansing cultural shower of loud classical music.

He only ever had a maximum of twelve clients on his books at any one time, because he believed that any more would place too great a demand on his time and energy, and he was resistant to seeking out, and paying for, any further assistance (he did have a long-serving secretary, tucked away in what looked and felt more like a cubicle than a room, but even her modest presence was more tolerated than embraced). He also made a point (after a brief and unhappy professional dalliance with a scatty young Thora Hird) of running a strictly men-only agency, claiming that women were simply 'too difficult to handle' because of their 'unpredictable' personal lives.

Among those actors whom he did represent for certain periods of time were Dirk Bogarde, Warren Mitchell, Roy Kinnear, Derek Nimmo, Joseph Tomelty, Eric Pohlmann, Donald Sinden and Denis Quilley, along with, of course, the every-patient and pliant John Le Mesurier himself. Joachim was, most of the time, a very good agent, much liked and trusted by his clients, but he could be exasperating on those occasions when his actors were growing anxious while waiting for offers of more work to arrive.

The main reason for this was the fact that Joachim's favourite dictum was that 'an artiste's greatest asset is his availability,' and, because he had such a low opinion of much that was being produced in the name of popular entertainment, his instinct was usually to turn down most offers in the hope that something better would turn up in the near future. While such a peculiarly Pickwickian outlook made perfect sense to Joachim himself, it tended to make rather less sense to those clients who were stuck 'resting' at home as they watched all the bills piling up on their door mats.

Perched high up inside his office at Remo House in Regent Street, as settled as a contented pigeon, he kept himself somewhat aloof from the minutiae of show business life, and made no attempt to actually promote his actors within the industry - good notices, he always said, was all the promotion they needed - and he simply waited patiently for any potential employer to pick up the phone and contact him. Stubbornly parochial (even America, complained one frustrated client, appeared to be 'beyond his ken'), his preferences for his charges placed London's West End right at the top, followed by, basically, anything and everything else, with their respective positions arrived at mainly by the size of the price.

Le Mesurier, like most of the others on the agency's books, rarely saw Joachim in the flesh. They would meet once a year for lunch at what might loosely be described as a London restaurant (as Joachim was paying, it was usually the cafeteria at his local Bourne and Hollingsworth department store), but during most of the months in between their contact tended to be limited to written correspondence and telephone calls.

Joachim regarded Le Mesurier, with his air of cat-like distractedness, as a client who required simple but stern instructions. While he knew that the actor, if left to act on his own inclinations, would probably disappear for days down into the darkness of a basement jazz club, he also feared that, once back up and out and blinking into the mid-morning light, he would be dazed enough to drift into whatever offers of work he happened to wander, so the agent was forever intervening to keep his client, as far as he was concerned, on the straight and narrow. 'Less is more' was one of his mantras - 'Always keep yourself a little bit rare, John,' Joachim would tell him - and so the longer that Le Mesurier would stay in a television show, the more miserable Joachim tended to get. There were plenty of programme-makers who craved the crafty character acting skills of the man they called 'Le Mez,' but, thanks to the protectiveness of his agent, only a few managed to reach him with an offer.

Probably the most notable of all the jobs that Joachim very nearly managed to lose for Le Mesurier was a role in a proposed new BBC sitcom called Dad's Army. The project's producer and co-writer, David Croft, knew all about the agent's attitude to television, having haggled with him over several other clients in the past, and so on this occasion - late in 1967 - had decided to bypass the gatekeeper by sending a copy of the pilot script directly to Le Mesurier himself.

Le Mesurier read the script and, although he tended to be a pessimist about such things, thought that it might just possibly have the potential to serve as the basis of a series, but he was rather anxious about saying so to Joachim. The agent - already fretting, as usual, over all the potentially 'better' engagements that he feared might be lost due to the actor's involvement in his current long-running show (the ATV sitcom George And The Dragon, which was about to commence filming for its fourth series) - was never going to welcome the prospect of tying him up to what could become yet another time-consuming TV commitment, and the naturally diffident Le Mesurier dreaded the thought of having to argue about it.

He decided, therefore, to call Joachim and merely mumble something vague about probably being willing to take the job if he thought the price was right, and then he sat back to see what transpired. When Le Mesurier subsequently found out that his old friend Clive Dunn had also been offered a part, he nudged his agent again, mumbling something slightly less vague, to see if a decent fee could be agreed.

The sighing and eye-rolling Joachim, after grumbling once again about the dangers of continuing in TV (which included, he warned, the relatively low pay compared to movies, the loss of freedom and flexibility, the trap of typecasting, and so on and so forth), grudgingly started negotiating with the BBC, just when David Croft's patience was coming perilously close to snapping, and, eventually, a deal was agreed.

Le Mesurier would, of course, go on to make the role of Sgt Arthur Wilson one of the great characterisations in British sitcom history, and also cherish the rare sense of camaraderie that came with being a member of such a talented and tightly-knit cast. Only Freddy Joachim continued to express any regret at the success that the show was enjoying: 'You're stuck now, John,' he moaned. 'I told you so, didn't I? I did tell you so!'

It was only from the early 1970s, after Joachim - having reached his late sixties - had decided to retire from being an agent, that Le Mesurier was able to start being the kind of jobbing actor who went more rapidly from job to job. Now represented by the more pragmatic and easy-going Peter Campbell, and pushed on when required by his far more positive-minded wife Joan, Le Mesurier suddenly found himself much busier, and better-paid, even though, without the pickiness of the ever-protective Joachim, the quality of the commissions would vary rather more than they had done before.

The artistic highs, though few and far between ('a good part comes about maybe once every five or so years, if you're lucky'), were deeply satisfying. His performance, for instance, in Dennis Potter's 1971 play Traitor - an edition of the BBC's drama strand Play For Today - proved a huge success, eliciting Le Mesurier some of the best critical reviews of his career, as well as winning him a 'Best Actor' BAFTA. Among his other rewarding engagements would be roles in the likes of Jabberwocky (1977) and Brideshead Revisited (1981), as well as several one-off TV dramas, along with a delightfully quirky album called What is Going To Become of Us All? (1976).

The commercial highs were rather enjoyable, too. Le Mesurier was happy to accept, for example, a series of lucrative commercials for BOAC (later British Airways), to be filmed in Hong Kong and Australia, in which he was to play a character very much like himself: an extremely laid-back, rather vague and effortlessly charming English gentleman heavily reliant on the kindness and professionalism of various cabin staff and ticket clerks. There were also countless voiceovers for a wide variety of other ads, ranging from Castella Court Cigars to Cadbury's Wispa bars (and he teamed up with Arthur Lowe for a butter commercial).

Somewhere between the prestigious projects and the profitable promo spots, however, were the kind of downright weird little ventures that would have had poor Freddy Joachim racing for the anti-acid tablets. One of most egregious of these was an obscure mid-Seventies production by the name of The Culcheth Job.

The catalyst for this strange little enterprise was the burgeoning career of Brian Culcheth, who was, at the time, quite a big name in the world of motor sport. A highly successful and much-admired British rally driver, with a long association as a works driver for BMC/British Leyland, he was actually a very modest and unassuming individual when outside of the breakneck battles of the racetrack, but his patrons had decided that he had reached a point in his progress when his public profile was ripe for further promotion.

Knowledge of this alone, however, did nothing to explain their interest in John Le Mesurier, because he was most certainly not interested in them. Motorsport, as he would have put it, was not exactly his 'bag'.

Cricket and horse racing remained his outdoor activities of choice, and, while he appreciated cars as a convenient mode of transport, he had so little emotional attachment to them that, once seatbelts became compulsory, he professed himself 'bored with the whole thing,' and unceremoniously abandoned his own vehicle beneath the Hammersmith flyover and then hitchhiked his way back home. He did feel a certain kinship with the more raffish type of racing driver, such as the suave Graham Hill and the saucy James Hunt, but was no fan of 'all that noise' and stayed far away from any meetings, in the flesh or even on TV.

When the offer thus arrived to appear in a short comedy film about a British motoring hero, he was more than a little bemused. He had skimmed past the name of 'Culcheth' occasionally in the sports pages of his daily newspaper, but still required some filling-in before quite grasping his sporting significance. He warmed to him a little more when he found that the driver was based in his own home county of Bedfordshire, but was still unsure as to why his own participation had been requested.

Once, however, Le Mesurier was assured that his presence would only be required for 'about a day,' and that (as filming was set to take place in and around London) he would not have far to travel, and that he would be reasonably well-paid for his performance, he decided, now that he was Joachim-free, to go ahead and take the job. 'It'll buy me and my chums a few drinks,' he smiled as he signed the contract.

Sponsored primarily by British Leyland, The Culcheth Job had been conceived as a half-hour-long light-hearted 'heist' movie short designed to showcase the talent of Culcheth for a broader audience (of the type and size that was currently helping to make the similarly successful motorcyclist Barry Sheene such an excitingly marketable personality) as well as boost the sales of a range of current Triumph cars. The plan, it seems, was to screen the finished product at various industry events, and also, it was at least hoped, slip it into cinemas as the support feature before the main attraction.

It was this sense of ambition that saw the producers go to the trouble and expense of assembling a surprisingly impressive team of filmmakers. Bill Young, for example, was persuaded to be the producer/director. He might not have been a household name, but nonetheless was an experienced chronicler of motorsport action, having supplied ATV and other broadcasters with many news packages of key meetings, and was well-suited to delivering (without any mechanical mishaps) the kind of fast-moving narrative that was required. The choice of screenwriter, Geoff Parsons, was comparatively uninspired - his comic footprint, at the time, was featherlight - but the editor, Lewis Fawcett, was already starting to make a name for himself in the area of sports-themed productions.

The choice of the cinematographer, meanwhile, represented a genuinely major coup. It was none other than Christopher Challis.

One of the country's most respected masters of the art (Martin Scorsese was a fan), and a distinguished student of Powell and Pressburger, his credits included such varied productions as The Tales Of Hoffmann (1951); Genevieve (1953); The Spanish Gardener (1957); The Grass Is Greener (1961); A Shot In The Dark (1965); Arabesque (1967); Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968); and The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes (1971). It was as impressive as it was surprising, therefore, to have him on board for such a modest-sounding niche project.

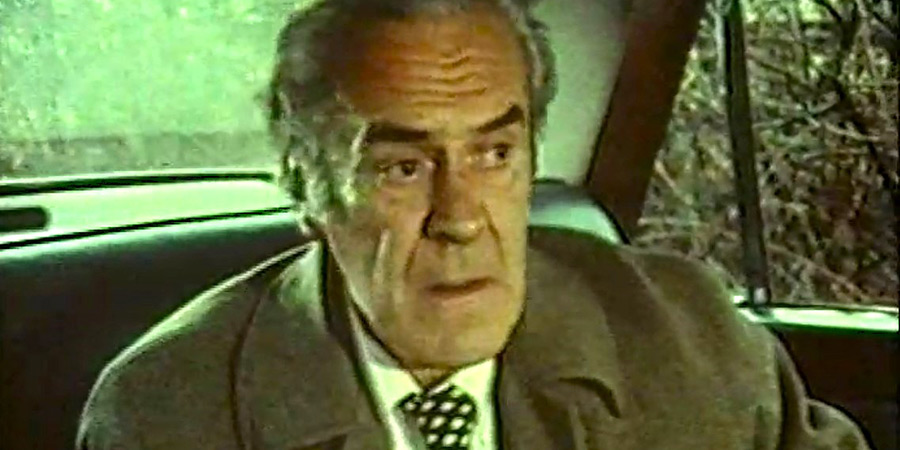

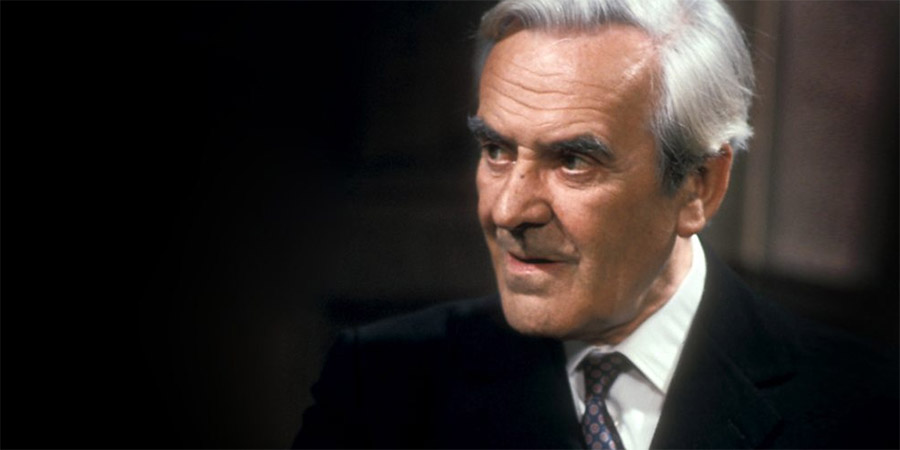

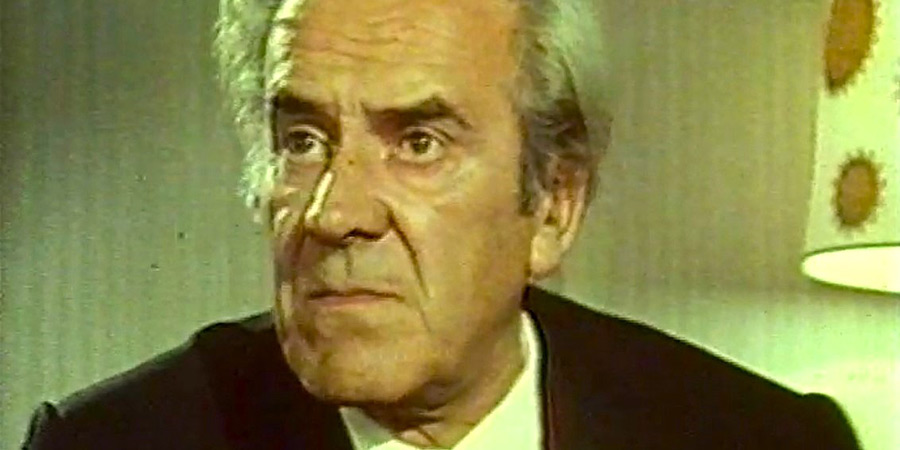

The same could have been said for John Le Mesurier, who was booked to appear as Major Richard Hornby - a rather world-weary criminal mastermind who was looking to complete his next 'flawless' caper as quickly as was possible. It was hardly a detailed or demanding dramatic role, but the producers knew that, with his talent, he could make the character work, and, with his popularity, he would at least pique the curiosity of the non-specialist viewers.

The cast was completed with the recruitment of several more fairly experienced character actors. Ray Edwards (who had previously popped up in minor parts in the likes of The Saint, Paul Temple and Casanova '73), Bill Sully (a busy stuntman in British TV who had also been credited with roles in such shows as the adventure series Adam Adamant Lives! and the sitcom Love Thy Neighbour), Olga Anthony (a peripheral figure in such Hammer horrors as The Vampire Lovers), Eric French (another minor supporting player in various TV drama series) and Johnstone Syer (not an actor as such but rather a good friend of Culcheth's and a leading rally navigator of the time).

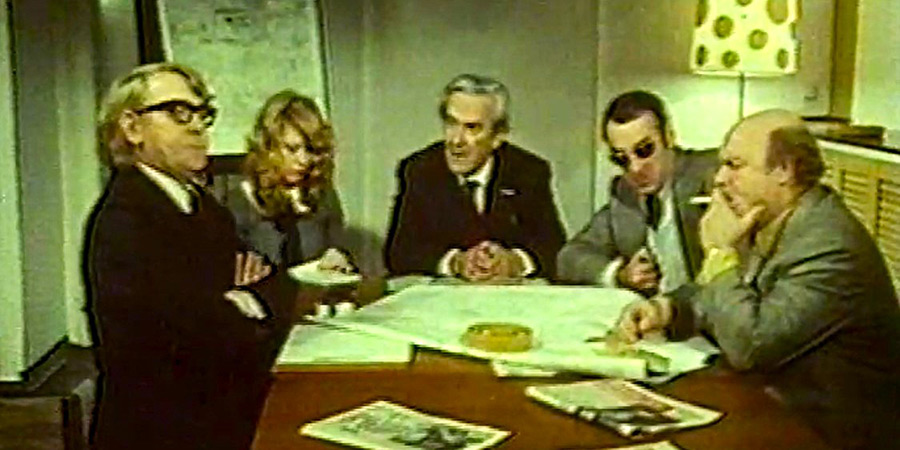

The movie begins in London, somewhere near Liverpool Street, in Hornby's office. He is presiding over a meeting of his colleagues - a small team of serial hijackers - who are mulling over a list of promising options for the individual ('a really first class person who can tackle this kind of job with his eyes shut') who might serve as the unsuspecting getaway driver to assist them in an imminent security van robbery.

It is at this point that Hornby suddenly spies a newspaper story about none other than the rally driver Brian Culcheth, 'the true professional' as the headline puts it, and, excitedly, he decides to scrap all the other candidates there and then. 'Well, ladies and gentlemen,' he announces, 'I think we've found the driver we're looking for!'

He then gets into his chauffeur-driven car and goes in search of Culcheth, whom he finds, very conveniently, strolling down the pavement a couple of streets away. Inviting him inside the vehicle, Hornby tells him a tall tale about how one of his companies is about to make a movie called Hijack, and they are looking for someone able to perform the elaborate and high-speed stunt driving for the action sequences, as well as provide some expert practical advice as to how the race to safety might best be executed.

Culcheth - who, to put it mildly, is clearly not a natural actor - takes all of this in with the look of an increasingly dyspeptic man pondering the provenance of the doner kebab that he has just gobbled down. 'It sounds fun,' he says, unconvincingly, now looking as though that doner kebab is well on its way back up.

They get out and go for a walk, so that Hornby can fill-in some of the details relating to his new colleague's duties. He then dispatches the still somewhat anxious-looking Culcheth to a garage where one of his accomplices is waiting to set him up with a getaway car.

At the sight of the pool of motor cars, however, the driver suddenly sparks into confident and decisive action, pushing down on bonnets, kicking wheels and doing various other manly things until he declares that none of the vehicles will do. He then calls for two British Leyland-made cars: a Morris Marina and a Triumph Dolomite.

'You'd better fix him up with what he wants,' mutters Hornby when called about the matter. The accomplice goes on to protest that this fresh-faced newcomer is being a proper pest: 'He's given me a list as long as your arm: rally tyres, shock absorbers, sump guards, Castrol oil - you name it, it's down here. I could bloody nearly build another car!'

Hornby, however, is in a hurry to move things on. 'Just get on with it!' he snaps before slamming down the phone.

After setting the plan into action, Hornby then spends most of the rest of the movie relaxing in his luxury apartment, either sipping brandy or adjusting - very slowly - his young female friend's décolletage.

Culcheth, meanwhile, goes off alone for a beer or two before returning the following day, smartly uniformed and helmeted up, to work his magic from behind the steering wheel. Now in his element, Brian proceeds to drive all over the place at great speed, and at great length, shouting as he goes about throttles and gears and acceleration, reducing the criminal in the passenger seat to a gibbering wreck long before they finally screech to a halt.

Quite the oddest moment in the whole movie arrives mid-drive, when, in a sudden burst of Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt, a voiceover from the real-life Brian suddenly begins over the basic faux-life Brian soundtrack, so that while one Culcheth continues to chatter away within the fiction, another Culcheth chatters away outside of it in a calmly reassuring tone that suggests he is adding information for real-life petrolheads to jot down for future use ('Sometimes you provoke the car into a slide, particularly for a corner that's a bit tight...').

Then, at last, the action moves on to the scene of the actual heist, which sees Brian (accompanied for security by Holby's glamorous secretary) race to a building site where an armoured truck has just been hijacked, collect the loot, and race off through the countryside to a waiting private plane. The crooks who have been following him in the second car, however, prove far less competent drivers during all of the high-speed twists and turns, and crash half-way to their destination, ending up being cuffed by the cops.

Now it's only Brian, and his attractive new female friend, who are free to fly off with what they call in the stealing business 'the dough'. In another sudden playful moment of meta-comedy, Brian finds that his pilot is none other than his old real-life mucker Johnstone Syer, who gives the camera a conspiratorial 'That's All Folks!' grin as the plane takes off and the credits start to roll.

It was, all in all, a thoroughly odd piece of filmmaking, but was the kind of low-key one-off project that John Le Mesurier, by that advanced stage in his long career, rather enjoyed. Having been made to behave himself by Freddy Joachim for so long, he simply found it fun to be doing something so utterly strange and silly.

What should not be ignored is how, regardless of the fact that it felt rather like a holiday for himself, he still made sure that he showed proper respect to those for whom it was just work, and he definitely impressed those on set with his easy-going professionalism. Brian Culcheth himself would later recall for me: 'I had such a lot of fun making [the movie] and it was such a privilege to work with John Le Mesurier. One that I am sure many professional actors would have wished for. He was so helpful in guiding me with advice and little techniques'.

It was true. In the short time they had together, Le Mesurier talked Culcheth through the scenes they shared, advising him on how to listen and look, where best to catch the cameras and the lights, and how to make the most of what few lines that he had. No matter how cheap and cheerful the actual filmmaking process appeared, Culcheth knew that the insights he was receiving were, as he reflected, 'priceless'.

Released in 1974, The Culcheth Job revved up and then promptly chugged-chugged-chugged to a halt like a Robin Reliant starved of petrol. Offered to but rejected by numerous small provincial cinemas, it was destined to be seen only by various groups of employees of British Leyland, Unipart and Castrol (who jointly organised a few 'free evening viewings' on their own premises), as well as by some puzzled punters at a couple of rally meetings. So far did it fall straight into obscurity that the movie is seldom even included in any of the participants' respective filmographies, and remains absent (at least at the time of writing) from any listings in the Internet Movie Database.

It was certainly a decidedly strange and morally-muddled way to promote either British Leyland or Brian Culcheth: a movie about the importance to criminals of finding fast and reliable cars and using smartly efficient drivers to pull-off a proper robbery was surely hardly the most prudent way to flog more cars or polish a sportsman's public profile. Even though the bad guys got their comeuppance right at the end, Brian was allowed to get both the girl and the goods without incurring so much as a speeding ticket.

'Them's,' British Leyland might well have said, 'the breaks,' or rather the lack of them. As for what this abrupt left-turn into the film world achieved for the company, it seems to have been about as little, and as dubious, as most of the other things this organisation attempted on the road towards its own demise.

Brian Culcheth, meanwhile, emerged unscathed from this most unlikely of his starring vehicles, mainly because it received next to no media attention and was seen by so few people. 'It was all a bit like a dream,' he would tell me. 'We just did it, it was a bit of fun, and then we moved on'.

John Le Mesurier would no doubt have said much the same. When he saw the finished film in a Soho viewing room, it was said that, at the end, he merely raised an eyebrow, let slip a subtle smirk, and wandered off in search of a large glass of whisky.

In the weeks and months that followed, he would accept an invitation to appear alongside Gene Wilder, Marty Feldman and others in the movie The Adventures Of Sherlock Holmes' Smarter Brother, did a voiceover for a marmalade ad, played a role in an episode of the TV series Orson Welles' Great Mysteries, held talks about recording some readings of Bible stories, had his photo taken holding a chocolate bar, signed up to provide the narration for a new animated TV series called Bod, and started rehearsing the forthcoming Dad's Army stage show. He even found time to squeeze in an appointment to open a school fete in Acton.

For a proper jobbing actor like John Le Mesurier, it was all just another day's work.

Help British comedy by becoming a BCG Supporter. Donate and join us in preserving, amplifying and investing in comedy of all forms, from the grass roots up. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more