Bring me fun: The brilliance of John Ammonds

John Ammonds, to adapt a famous line from Hey Jude, could take a funny show and make it better. In the history of British broadcasting, there was simply no other light entertainment programme-maker who was more assiduous, rigorous and judicious at assessing the full potential of each and every aspect of a show and making sure that it was realised on the screen.

From the start of the 1960s to the end of the 1980s, there was an integrity about his approach to making comedy shows that was unparalleled in British television. From the script to the performances to the whole experience beamed from the screen, there was nothing that he had not lifted up to a higher level. Harry Worth, Dave Allen, Dick Emery, Mike Yarwood and, of course, Morecambe and Wise, along with many other performers, became better entertainers through working with this man.

Ammonds possessed all of the key skills required of a truly great producer/director: he was a calmly efficient organiser and encourager of diverse talents, temperaments and techniques; he could be creative and flexible as well as disciplined and managerial; he possessed an exceptionally sharp eye and ear for detail; and, last but by no means least, he always acted as though he was the servant of the public rather than his profession. The most polished of populists, he epitomised the BBC's traditional dictum about 'giving viewers what they want - but better than they expected it'.

He was born in Kennington, London, on 21st May 1924, to working-class parents. His mother, one of sixteen children, had only married his father, a watch-maker, in a 'shotgun wedding', and John would later say that he 'only remembered the arguments' between this 'quite unsuited' couple during his formative years.

It was his father, however, who introduced him to the world of entertainment. As a 'frustrated actor' with a passion for the work of Charles Dickens, Ammonds Senior sometimes co-opted his son into the amateur dramatic troupe he had formed - 'The Dickensian Tabard Players' - to tour the workhouses and prisons in and around Southwark. One of the most vivid memories John would retain of these juvenile performances was of the occasion when, aged about thirteen, he appeared as Oliver Twist in a production staged inside Holloway Prison before an audience of 'extremely interested' women prisoners: 'They were good and only started shouting and screaming after Bill Sikes had killed Nancy!'

Although John won a scholarship to a grammar school at Sutton in Surrey, he found much of his education uninspiring, preferring to amuse himself at home by constructing a variety of crystal and cat's whisker radio sets in his father's garden shed. Rather than stay on to complete his Higher School Certificate, he elected to leave at the age of fifteen and instead sat the entrance examination to become a civil servant at the London County Council (mainly because, he later explained, it seemed to promise 'a job for life and a pension at the end of it'). After sampling the position on a part-time basis, however, he concluded that it offered nothing more as a prospect than 'decades of sheer boredom' and decided to try something else.

His career in broadcasting began in 1941, when a speculative letter sent to the BBC asking if there were any openings for a 'junior engineer' led to him being invited to apply to become a sound effects operator in the Corporation's Engineering Division. Once accepted, he spent the next thirteen years acquiring invaluable experience working in the BBC's Variety Department at London, Bristol and Bangor.

The fact that he began training during wartime meant that he faced some extraordinary challenges coping with unpredictable 'live' situations. He was providing sound effects for the popular radio show ITMA, for example, on the night that a couple of bombs were dropped on Bangor. They were recording the proceedings one Sunday inside Penrhyn Hall, a Victorian concert venue rented from the local council, when the earth suddenly shook.

'I think a German bomber must have got lost after flying over Belfast,' Ammonds would later tell me, 'and he decided to jettison what he'd got. I was doing the usual sound effects that night, you know, like blowing bubbles into a soup bowl to suggest a deep sea diver emerging from the water, and just then you heard this loud crunching noise, and all this dust was falling all over the place, while the bandleader Charlie Shadwell was conducting the number, It Ain't What You Do, It's the Way That You Do It. I don't think the pilot heard. Anyway, it turned out they'd already faded us out in London, but we didn't know that and so we kept going for a bit until we all got herded out.'

It was, in a perverse sense, invaluable training. 'After that,' he would later remark, 'you couldn't get overly panicked by some minor technical problem. Let's say it gave you a healthy sense of perspective.'

After serving in the Army for several years as part of a broadcasting unit in Hamburg ('I ended up being promoted to twiddling knobs and mixing sounds'), he re-joined the BBC in 1947 as a programme engineer in light entertainment, and then, in 1954, applied for and got the job of a radio variety producer in Manchester.

He had found a niche. By the mid-1950s, he was responsible for several successful radio series, working with such popular northern performers as Ken Platt, Jimmy Clitheroe, Dave Morris and, in their debut series, Morecambe and Wise. 'I loved the freedom I had to make a programme,' he would say. 'I had a hand in the script, the jokes, the sound, the direction and dealing with the guests and the stars. It was hard work but very fulfilling.'

Moving into television at the end of the decade, he found his first protégé in the form of Harry Worth. 'I consider Harry to be one of my greatest successes,' he would later tell me. 'The reason why is that I felt I really helped him progress. He'd had this rather primitive stand-up comedy act that he'd been doing for ages with two ventriloquist dolls, but I put him in a situation comedy. We did a pilot in Manchester - we wrote it together - and then sent it down to London and we got a series commissioned. And from that point on he went from strength to strength.'

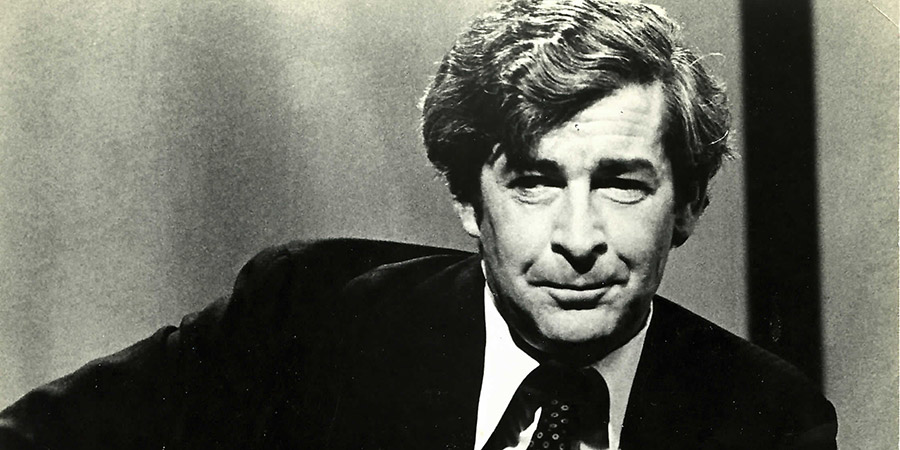

Another comedian whom he helped develop as a television performer was the Irish stand-up Dave Allen. Their association began in 1965, when Ammonds was producer of The Val Doonican Show and Allen, having recently made a name for himself on Australian TV, was back in Britain building up a following on the club circuit.

Bill Cotton - then Head of Variety at the BBC - had seen Allen performing and thought that Ammonds would be the ideal mentor to help him on his way to stardom. Ammonds agreed to give him a regular slot on the Doonican show, and, sure enough, very quickly became, along with Cotton, one of his most important champions:

It was ironic, really, because when Bill Cotton had first mentioned Dave to me, and before I'd actually gone to see him perform in a club, I'd been a bit worried about whether he'd have enough material to fill each five-minute slot in a series that was going to run for eleven weeks. Of course, once I saw him do his act I realised that one story could take him five minutes to tell! So he was no trouble at all. I could bring the camera in, and he could draw the audience in, and then he'd hold your attention throughout what were sometimes quite long and elaborate jokes - and that was a real achievement. He was probably the one comic I'd known who could get, if anything, even bigger laughs at various points all the way through a joke than he got at the end on the tag line. He really did work extremely hard to get his material across, and yet he made it look effortless - which was the art, of course. So he was perfect for the show right from the start, and such a pleasure to work with because he listened to advice and learned very quickly.

While his performers enjoyed rapid success under his guidance, Ammonds himself, at least internally at the BBC, soon won a reputation not only for the competence of his productions but also for his knack of accentuating the personality of his stars. It had been his idea - following a prompt from the writer Vince Powell - to begin the whimsical Harry Worth shows with the much-mimicked optical illusion, involving his 'levitated' reflection in a shop window. It was also his idea to get the ultra-relaxed Val Doonican to croon one song each week while sitting in the rocking chair that ended up being his trademark. He had that ability to engage with the essence of a performer, and wrap around them a show that seemed authentic, appealing and characterful.

It was after he was reunited with Morecambe and Wise in 1968, however, that he achieved his greatest success, proving himself, not only as producer/director but also as an all-purpose creative sounding board, as invaluable to the pair as George Martin had been to The Beatles. He taught them how best to use their talents for television, turning their show into the most admired entertainment of the time.

The first clever thing that he did was to make Morecambe and Wise relax. He realised that, although they had been regulars on commercial television for the best part of a decade, they still felt most comfortable in a live theatrical environment, so he made the television studio seem more like an old variety venue, with tableau curtains and an elevated wooden platform.

As he later explained to me, it was not the most convenient of moves from a technical point of view, but he was determined to get the best out of the double act, and knew that this was the way to do so:

Eric and Ernie never, ever, got used to the idea of working on the studio floor with a television audience. They always had to work on a specially-built stage. I was rather horrified at the very beginning when they said, 'Oh, by the way, we like working on a two-foot-high stage,' because that meant that all of the cameras were going to have to crane up higher, and having that platform there was going to make it more difficult to set things and strike things. But they wanted the studio to feel more like a theatre, you see, and I understood what they meant. I'm not sure they really saw that much more from the platform, because the cameras were still in the line of sight - they had to be, because otherwise they would have been shooting up Eric and Ernie's nostrils! - but it was all about trying to recapture that special kind of atmosphere that they'd had in their touring days.

The next thing that he did was to coach Eric Morecambe how to better understand the relationship he could and should have with the TV cameras. This coaching consisted of two phases, with the first one concerning the need for greater discipline:

As a director, Eric - at least to begin with - would be a bit of a problem, because he wouldn't be exactly in the same place twice running, and if you had the temerity to suggest to him that he should be in exactly the same place twice running you'd probably get a rude word back for your trouble! I do remember, in those early days, I'd press the talk-back key in the control gallery and ask the floor manager to get Eric to move a couple of feet to the left or something and I would hear him shouting, 'This bloke'll be having us on chalk marks next!' or 'Ye gods, he's after an award up there!' It was all good-humoured, of course, and I gradually got used to working in a certain way that enabled me to get a camera script out of it that was, shall we say, 'flexible'.

The second stage of this coaching involved making Morecambe realise how he could exploit the cameras rather than merely endure them. Up to this point, Ammonds believed, some of Morecambe's genius was missing from the screen because he hadn't yet realised fully how the camera was the key to effecting a sense of intimacy with the viewing audience.

'It took a while to persuade him,' Ammonds later reflected. 'The thing was, in the past, he'd still think in stage terms - he'd picture how a routine would look to an audience in a theatre, who could see the whole thing - and so he'd been very resistant to the camera coming in and only showing a detail of it. That to him felt like a loss of control - it felt like the director was undermining how he wanted his performance to come across. So I really worked hard to make him see not only why we sometimes needed to come in close, but also how he could use the close-up as one more comic technique. I think that clinched it - but it did take a while to make him trust me!'

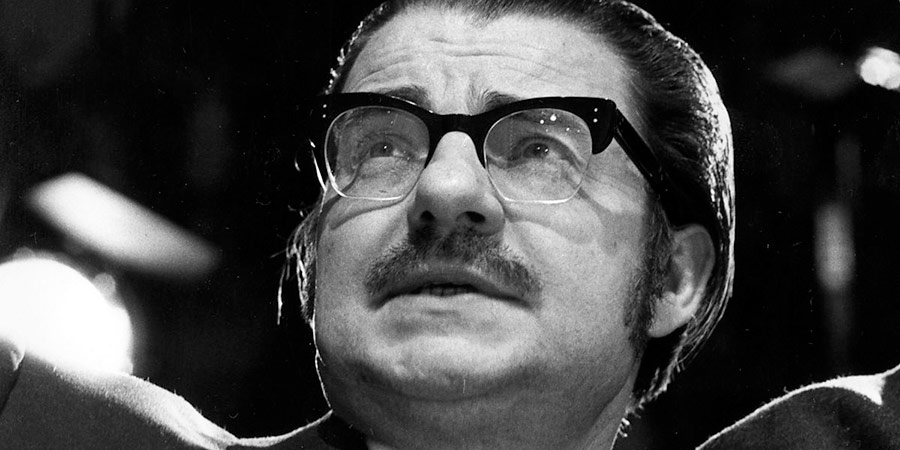

The actor Francis Matthews, who appeared alongside them during this period (above), later confirmed to me the impact Ammonds's instructions would have:

John really taught Eric - and Ernie - how to exploit the fact that they were on TV rather than the stage. I mean, as an example, the way in which he got them to make more use of the close-up: you know, that close-up of Eric grinning at the camera while Ernie was talking, or glancing into the camera and whispering, 'This boy's a fool!' - that was John's innovation. He also brought in more close-up reaction shots. Eric took a bit of time to see the value of those and learn to perfect them. I remember the first time I was on the show with them, Eric would be saying to John, 'Ah, no, Johnny, you want us in full-length! You don't see Fred Astaire dancing with only a close-up of his face, do you? Come on, show all the physical movements, all the hand gestures, it's important!' And John would say, 'Eric, we're on television, and it's like film - it's a close-up medium. Of course we want to have the long shots and medium shots and all of that, but some of the reactions can be very small and we have to get up closer to you'. Obviously, Eric - once he'd got used to it all - became just brilliant at it, but for a short while he was looking around at the cameras and going, 'What's he doing now? What's he up to? Where's he gone now?'

Among Ammonds's other distinctive contributions was the droll little dance with which Eric and Ernie ended each performance. It was a sign of his willingness, along with all the meticulous planning, to leave room for spontaneity and serendipity:

I just happened to be watching this Marx Brothers film on television one night. Horse Feathers. Groucho had taken over the campus, I think, somewhere in America. Anyway, at one point, he did a musical number or something, and he did this silly dance, you see, putting his hands behind his head and sort of hopping in the air. I found it amusing, and, the next morning, I came into rehearsal and I said to Eric - who was a big Groucho Marx fan - 'Did you see him last night?' He said, 'No?' So I said, 'Well, he did this funny dance at one point...' And I did it all the way around the room, you see, and both of them laughed like mad!

Well, we carried on rehearsing for the next show, which was due to be recorded in about a week's time, and then - I think it was on the dress run-through - after singing Bring Me Sunshine, they danced off with that funny dance! And they kept it in for the recording, and after that they did it every week. It became a trademark. And if I hadn't come across that film that night, and liked that little dance, it wouldn't have happened. So I can say: me and Groucho - we created it!

Another invaluable idea was his deployment of 'serious' star guests as unlikely comic stooges. 'That really took off,' Ammonds later explained, 'because of the fun we had early on with Peter Cushing. He was used to doing drama and films, of course, so it was something of a gamble to book him for our show, but he was such a wonderful sport, pretending to complain about not being paid, that he made me think of who else we could get.'

Ammonds went on to persuade a remarkable number of distinguished celebrities to come on and be teased by Eric and Ernie. Laurence Olivier was shown trying to avoid them on the phone by pretending to be a labourer at a Chinese laundry; Rudolf Nureyev was informed that he owed his big chance to the sudden indisposition of Lionel Blair; Dame Flora Robson had a pint of ale poured over her arm; Yehudi Menuhin was reminded to turn up with his banjo; Vanessa Redgrave was taken by Eric to be a drunken member of the audience; Glenda Jackson was obliged to say such lines as 'All men are fools, and what makes them so is having beauty like what I have got'; and, of course, Andre Previn was grabbed by the lapels, slapped on the cheeks, made to jump in the air and urged to lengthen the start of Grieg's Piano Concerto 'by about a yard'.

'Having them come on gave the show something a bit different, a bit special,' Ammonds said, 'and I also knew it worked well for Eric because it gave him the chance to work like Jimmy James - one of his heroes - had done, as the comic working with two stooges, in this case Ernie and the guest. Eric could do that brilliantly, of course, and having the odd routine with a threesome provided a nice alternative to all of the double act sketches. So it worked on more than one level.'

Ammonds also ensured, as writer Eddie Braben's amiably relentless taskmaster, that the standard of the scripts remained remarkably high. It was here, more than anywhere else, that his radio experience proved priceless.

Having spent so many years working in a medium where the quality of the word - as written and as performed - was crucial for the success of a show, Ammonds remained the most meticulous of script editors after he made the transition to television. Many experienced comedy writers would joke, very affectionately, about his forensic attention to detail - Barry Cryer liked to claim that Ammonds's favourite piece of music was Stravinsky's Rewrite of Spring, while Spike Mullins complained that when he sent the producer a Christmas card he got it back by the next post with detailed instructions for how to improve it - but all of them appreciated not only his discipline but also his decency. 'He really was one of the nicest of people to work with,' said Mike Craig. 'Men like him were rare then, and in today's television they don't exist at all.'

Eddie Braben certainly had nothing but respect for Ammonds, describing him as 'the best comedy man you could get'. The producer was the vital link between the writer and the performers, working hard to keep both parties happy whilst also pushing them on.

'Aside from my own opinions about the scripts,' he later told me, 'I also had to convey to Eddie the views of Eric and Ernie':

I needed to be careful about that, because the boys had this habit of laughing uproariously at what Eddie had written when he was there for the read-through in London, and then, once he'd travelled back to his home in Liverpool, they'd suddenly announce that they didn't like this and that. 'Can you tell Eddie?' they'd always say. I knew it was better that they left it to me to talk to him, because performers aren't always as tactful with their writers as they probably ought to be, whereas I'd learned over the years that you needed to be very tactful. For example, you'd never say to a comedy writer, 'No, that's no good'. You'd always say, 'Why not do it this way?' Nonetheless, I used to dread it sometimes, having to keep calling poor Eddie, not least because the boys preferred to make it seem as though I was always the one complaining, whereas they were perfectly contented. They used to get a bit shy like that!

Ammonds, however, always remained in control of the critiques. Sometimes he would side with Morecambe and Wise, and sometimes with Eddie Braben, and sometimes he would overrule both of them. Such was the authority that he had earned, the other three always accepted his decision as final.

'He is very honest,' Braben confirmed at the time. 'If he doesn't think a sketch works, he will say so and we will trust his judgement totally and abandon it. Or he can suggest the single gesture or line that could bring it to life.'

One final thing that Ammonds brought to the show was a sense of humility, and a genuine respect for the audience. A John Ammonds production was never done, primarily, to please his bosses, or his performers and writers, or the critics, or himself. It was always done to please his audience.

'We weren't interested in going out of our way to offend people,' he told me. 'That wasn't our way':

I remember we once did a sketch where, for some reason or another, a girl came to the door of the flat, and she was obviously pregnant, and Eric thought that Ernie was the father. Well, we received about a dozen letters about that, saying this was a bit much for Morecambe and Wise, you know. We'd get very upset about that, and we'd feel that we'd made a mistake - that we shouldn't have done it. Of course, you have to put it in proportion: we had twelve letters of complaint out of an average audience of a mere eighteen or nineteen million people! But I'm glad that it did worry us, because we didn't need to use any material that was remotely 'blue'. That was the thing: we didn't have to rely on vulgarity to make a genuinely funny show. We'd got Eric and Ernie, these two wonderful comic personalities, and, well, the world was our oyster.

He left The Morecambe & Wise Show in 1974, after eight series, mainly in order to devote more time to his beloved wife, Wyn, whom he had married in 1952 but was now suffering from the advancing effects of multiple sclerosis. 'It was quite a strain to keep our standards up,' he later explained, 'let alone keep trying to push them up even higher each year, and by that point I didn't feel I could devote all of my time and energy to it, along with looking after my wife, so, sadly, I left - but with Ernie Maxin taking over I was leaving them in very good hands.'

He continued, when practicable, to oversee numerous other productions, starting in 1975 with Lulu, and moving on to make some very successful series with Mike Yarwood, Dick Emery, Max Bygraves, Marti Caine, Bernie Winters and Les Dawson. He was also reunited once again with Morecambe and Wise when they asked him to supervise their final few shows for Thames TV.

Ammonds - who received an MBE in 1975 for his services to entertainment - retired from broadcasting in 1988. Based in Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire, he continued to help care for his wife until her death in 2009, and also acted as a wise, kind and generous advisor to many writers, documentary makers and historians (myself included) keen to chronicle the era of television he had graced. He passed away, aged eighty-eight, on 13th February 2013.

Sir Bill Cotton told me that he regarded Ammonds as one of the true greats of programme-making: 'The great unsung hero of The Morecambe & Wise Show, the one who never got an award - they got awards for everything - was Johnny Ammonds. He had enormous expertise, and he had great experience, and his eye for detail was spot-on. He really deserved one of those BAFTAs - and a whole lot more - for everything that he brought to that show.'

The BBC really ought to take note of its former Managing Director's words and come up with some kind of fitting memorial to John Ammonds. A BBC-funded 'John Ammonds Production Bursary' might be a fitting memorial, or perhaps a 'John Ammonds Comedy Direction Course'. BAFTA - having neglected the man during his lifetime - might also feel inclined to get involved, possibly with a new or revised category in his honour - 'The John Ammonds Award for Best Entertainment Programme' has a nice ring to it, as does 'The John Ammonds Award for Production Excellence'.

He truly deserves such public recognition. He made programmes that worked on every level, that tested talents and delighted broad audiences, and he did so with rare grace, intelligence and care - and for that he will always be missed, and for that he should always be remembered.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more